My immersive journey into the mind and work of Vincent Van Gogh began with a twenty-minute drive to the Circuit of the Americas, the motor sports racetrack outside of Austin. In the paved, arid expanse of COTA in summer, absent any landscape or human figure that might have compelled Van Gogh to pick up a paintbrush, I drove past five empty parking lots and into a sixth. There, a nondescript warehouse beckoned with a playful sign reading “Gogh This Way.”

I spent ten minutes winding past screens of text explaining, in hagiographic terms, the life of the Dutch Postimpressionist painter. I was instructed that, despite his suicide in 1890 at age 37 shortly after lopping off his own ear and offering it as a gift to a brothel maid, “Van Gogh’s work radiates joy and celebrates life,” and that “to experience his work is to open oneself to immense joy.” Steeled for delight, I reached the portal. My magic school bus ticket was stamped. It was time to go inside the paintings.

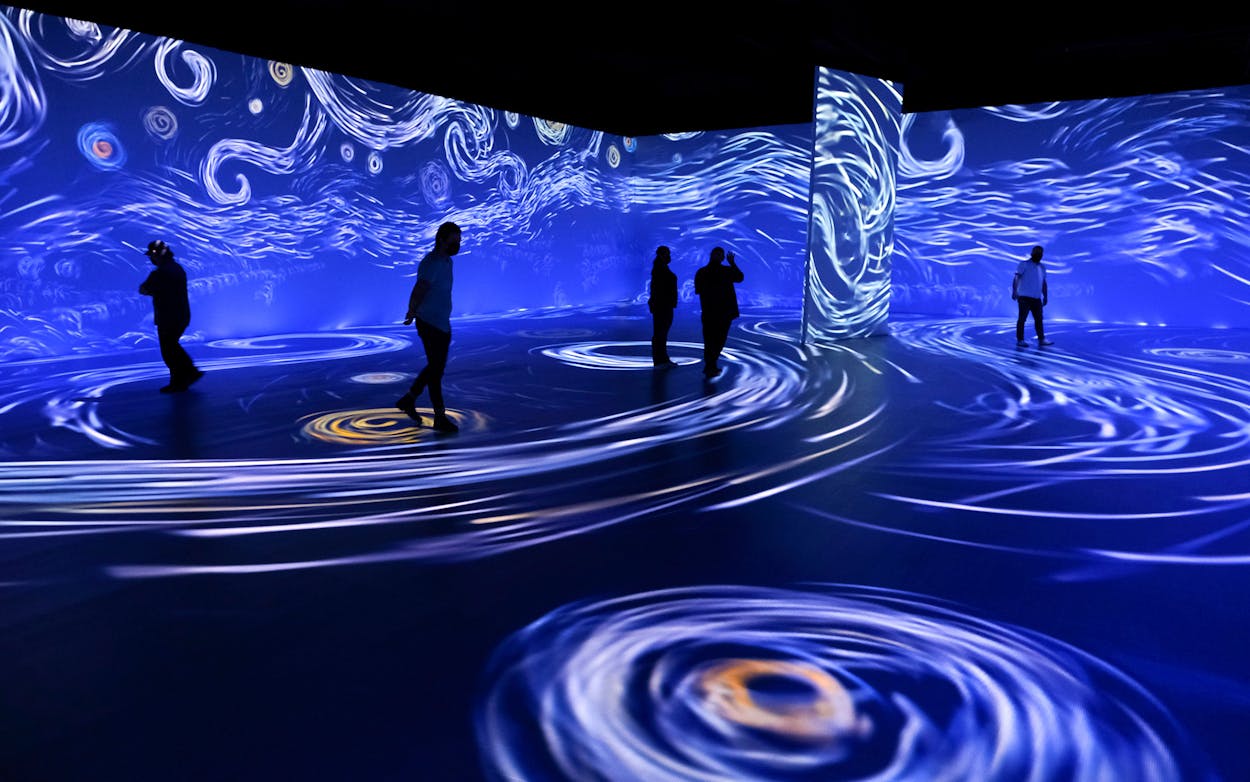

“Beyond Van Gogh,” which opened Friday in Austin, is one of a half-dozen independent productions of Van Gogh–inspired wall-and-floor projection shows appearing across the country. National arts reporters have struggled to distinguish the various shows on offer, which are the handiwork of different animators and composers, and to assess claims of being the “original” Van Gogh immersion—a dubious concept for infinitely reproducible exhibitions that traffic in public-domain digital images. Even the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin, who lamented the bygone “aura” of one-of-a-kind paintings and sculptures in his 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” would throw up his hands at the many layers of knockoff simulation at play. Tickets are in the $30–$65 range.

Montreal-based “Beyond Van Gogh” designer Mathieu St-Arnaud has said of his approach, “We wanted to go beyond the frame and step inside his world, inside his paintings.” A competitor series, “Immersive Van Gogh,” will roll out similar experiences in Dallas, San Antonio, and Houston starting in August. The claim to fame of this latter production is its brief appearance in the Netflix show Emily in Paris in 2020, arguably sparking the present craze. And to add to the confusion, Dallas, in fact, is double-booked with yet another variant of the projection-show fad. “Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience” is opening in July.

One critic recently compared these shows to “wall-size screen savers,” and the same thought occurred to me as I immersed myself in the spectacle. Pulsing, animated stars populate the walls, black-and-white sketches fill in with color, and viewers of a certain age will feel an instinct to nudge a mouse and get back to Windows 95. “Beyond Van Gogh” belongs squarely in the category of a boardwalk or tourist-center diversion. It merits consideration for dates and family outings alongside escape rooms, wax museums, and fun houses. (Speaking of, there are distorting mirrors at the entrance of “Beyond Van Gogh” that transform the visitor’s body into the swirling forms of late, haunted canvases like Starry Night, a cute trick.)

What “immense joy” can be found in “Beyond Van Gogh Austin” is accessible mostly to children and those in pursuit of their next great Instagram backdrop. My cold, elitist heart was mostly impregnable throughout the 45-minute show, but it did melt a bit to see kids chasing digital almond blossoms across the floor and gazing in wonder as the whole room shifted to pale blue. I also noticed more than one date that seemed to be going well, many successful photos snapped, and one or two journeyers inside the paintings whose trips might have been psychotropically enhanced. If others were, like me, a bit disappointed that the show was just one large rectangular room, with blurry areas where each projection lined up with the next and visible grid lines underneath all the images, I couldn’t tell.

The populist merits of “Beyond Van Gogh” should not be dismissed lightly. Watching the children at play, I had to wonder: when was the last time I’d seen kids that energized in a museum? It’s not easy for static paintings to capture our modern, digitally addled imaginations—if it were, shows like “Beyond Van Gogh” would flop. Instead, they’re thriving, perhaps because they offer us an echo of the pure spectacle that a Van Gogh painting show might have offered in his own time, when his bright-hued, almost frighteningly lucid paintings were just about the most visually stimulating thing one could ever hope to look at in, say, a gray Paris winter.

The argument for giving “Beyond Van Gogh” a shot goes like this: Museums in a minor art city like Austin are unlikely to land a traveling exhibition of priceless Van Gogh canvases anytime soon. That said, the Dallas Museum of Art will host a Van Gogh exhibit starting October 17, and tickets for special exhibits typically cost less than $20 on top of free general admission. But what’s the harm of encountering his work in an Epcot-style sideshow, for those of us who can’t travel to New York or Amsterdam to look at the real thing? Isn’t it a bit like watching a documentary?

The argument against is that it’s a bad documentary. “Beyond Van Gogh” sentimentalizes Van Gogh beyond recognition. To be fair, much of the heavy lifting has already been done in pop culture. Don McLean’s 1971 folk tune “Vincent ” is one of the melodies that plays in the background of the show, with its saccharine lyrics “For they could not love you, but still your love was true … This world was never meant for one as beautiful as you.” In contrast, the real Van Gogh’s most salient quality was not purity or poetic martyrdom but a dangerous, all-consuming emotional intensity that manifested itself in religious fervor, unrequited romantic aggression, self-harm, and—yes—fantastically beautiful paintings.

Van Gogh’s paintings are also famously textural. Digitizing the images and reducing them to a plane, we lose this. One thing “Beyond Van Gogh” gets right is including projected text of a Van Gogh letter to his brother, speaking of his peasant subjects: “I plow my canvases as they do fields.” The shape of the paint—the thick strokes and upswirls, the physical sense that this is work by one man—is central to the experience Van Gogh is after.

In his 1985 essay “The Production of the World,” the British art critic John Berger describes being stuck in a postmodern sense of unreality, where he “could no longer hold meanings together,” and then visiting the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and being cured of his malaise. Berger praises Van Gogh as an artist concerned above all with perceiving and communicating reality through paint. When he paints a chair, Van Gogh seems to join the pieces together himself. “His paintings imitate the active existence—the labour of being—of what they depict,” Berger writes. “…[H]e takes us as close as any man can, while remaining intact, to that permanent process by which reality is being produced.”

“Beyond Van Gogh” and its ilk labor in the opposite direction—toward cheap illusion; toward false commodification of a real, complex man and his art; and toward a divided and distracted style of attention ruled by technology, where we find ourselves finally inhabiting a picture of a picture of a picture.

- More About:

- Art

- San Antonio

- Houston

- Dallas

- Austin