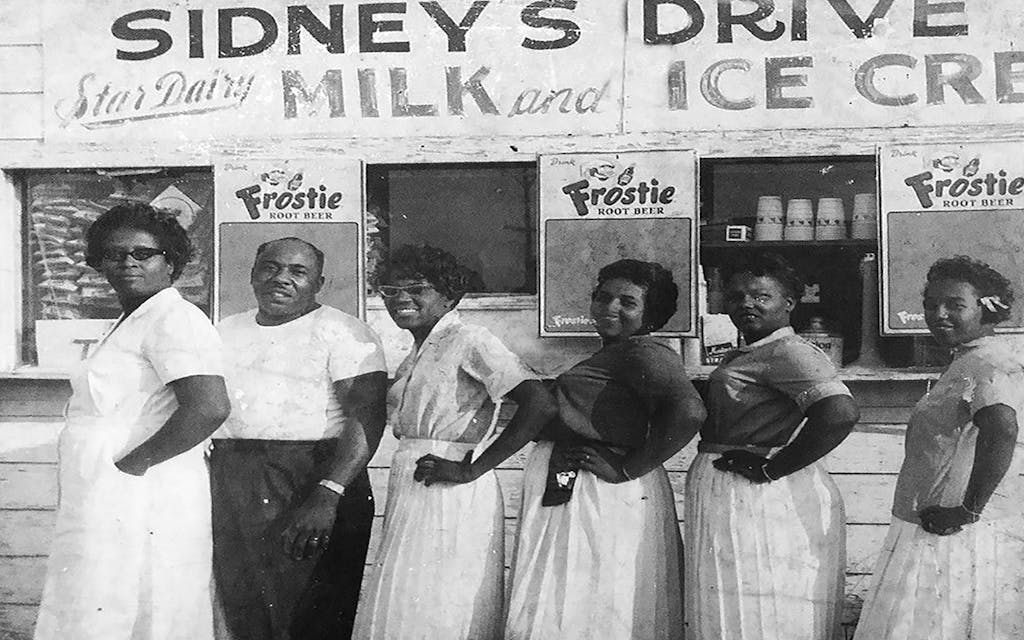

The joy is undeniable. Vintage photos show patrons relaxed, happy, and dressed to the nines, plates piled high with stuffed shrimp and jambalaya, cans and bottles of Schlitz beer strewn across tabletops in 1950s Galveston.

In the new book Lost Restaurants of Galveston’s African American Community (American Palate), locals rhapsodize about the taste of “mouthwatering pork bones, pork chops, crispy fried chicken and scrumptious meatloaf,” “mandatory Kool-Aid,” and “delicious pound cake topped with jelly icing” at Maggie “Big Momma” Fisher’s Twilight Grill. They recall cherry Cokes at T. D. Armstrong’s Drug Store, where it cost five cents to play a favorite tune, and where people congregated after school at Central High (Central High School was Texas’s first African American high school until federal widespread school integration in 1968).

“Are you old enough to remember Happy Days? That’s the way it was,” says one of the book’s coauthors, Tommie Boudreaux. “There was a jukebox in there, you could get sodas and drinks. One person I interviewed said, ‘I think he [T. D. Armstrong] did that for us because we didn’t have anyplace to go.’”

These memories of Galveston’s thriving Black community, buoyed by Black-owned diners, speakeasies, and pit stops mainly from the 1940s through the 1960s, are all captured in the book, published by the Galveston Historical Foundation earlier this year. Each chapter profiles restaurateurs and chefs based on interviews and archival research. Authors Boudreaux, Alice Gatson, Ella Lewis, and Greg Samford also include recipes passed down through generations from their own families, or from those who worked at Galveston restaurants, in an attempt to keep the flavors of Galveston from that era alive.

The authors are all members of the historical foundation’s African American Heritage Committee, which works to share African American history on Galveston Island. Proceeds from the book will support the restoration of Rosewood Cemetery, Galveston’s first Black burial ground, which dates back to 1911.

Galveston is the site of the original 1865 Juneteenth celebration marking the day enslaved African Americans were given the belated news of their freedom following the end of the Civil War. But in the years following the Civil War and Reconstruction, as in the rest of the United States, Galveston’s African American community contended with intense segregation and racism. White people excluded their Black neighbors from using the Island’s restaurants, schools, and even beaches. On the east end of the Island, a tiny, one-block area between Twenty-eighth and Twenty-ninth streets at the seawall was reserved for African American beach access. A World War I monument placed across from that beach listing the names of local fallen soldiers has a separate section for “colored” veterans, segregation extending even to their ultimate sacrifice for their country.

It was near here that local legend Andrew Augustus “Gus” Allen staked his claim. Allen started out shining shoes at the Hotel Galvez in the 1920s, and by the following decade, he became one of the Island’s first African American entrepreneurs, opening Gus Allen’s Cafe, which thrived well into the fifties, a white stucco facade at the corner of Twenty-seventh and Church Street painted with “Open All Night” and “Sea Foods, Steaks, Chicken Dinners.” Allen eventually opened several more businesses in the 2800 block of Avenue R ½, directly across from the African American beach. As we learn in the book, Allen’s little empire gave a boost to other local Black businesses, such as Albert Fease’s Jambalaya Cafe and local barbecue legend Nelson “Honey” Brown’s Honey’s Barbecue. Others followed into the 1960s. The book profiles more than a hundred bygone dining establishments in total.

“Even though things were supposed to be fully integrated in the mid-sixties, you would go places and they wouldn’t wait on you, or make you feel so uncomfortable that you didn’t go in, and so [African Americans] just had their own fun,” says Boudreaux, who remembers her mother and father shelling out money to pay their poll tax, a tool of voter disenfranchisement particularly aimed at Black Americans, even when funds were tight.

The book touches on the hardships African Americans faced in the Jim Crow South, but it also memorializes this era for the joy it brought to working Black families like Boudreaux’s and Gatson’s, for whom the occasional takeout order or a peppermint stick stuck inside a pickle from Sim’s Ice Cream Parlor was a special treat. Lost Restaurants paints a picture of a close-knit community enjoying good food, laughter, and libations. It was an era when big stars like Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughn, Etta James, and Nat King Cole all performed at Galveston’s City Auditorium, organized by Tip Top Cafe’s Courtney Bernard Murray, who put a little advisory on his playbills: “Section Reserved for Whites,” in a nod to restrictions Black Galvestonians had seen for decades.

Girls, Gatson and Boudreaux say, were prohibited from visiting many of these establishments unchaperoned by a parent, particularly after dark when the restaurants turned into clubs, so they don’t have a lot of firsthand memories. But they heard plenty of talk from their parents—“I didn’t get the chance to go to those places, but I heard Daddy telling Mama about it,” says Gatson. There were stories about underground gambling spots, where pinball machines disappeared at the first sight of Texas Rangers; bootlegged liquor sold for a few bucks’ profit when patrons’ BYOB alcohol stashes ran dry; respected Black teachers secreted away to special booths where they could get a little loose in private.

“For me, it was forbidden fruit; that’s why it looked like it was fun,” says Gatson, laughing. Boudreaux adds: “There’s always somebody who knows what other people are doing. You’d hear that one teacher got so drunk they had to take him home. They made their own fun.”

Today, there are a handful of thriving Black-owned restaurants on the Island (Leon’s World Famous Barbecue, Soul 2 Soul Cafe, and Allen’s Kitchen and Grill, among others), but the dozens of beloved African American establishments collected in Lost Restaurants are just that. The authors say the closures were one result of working toward a more integrated community. “We kind of lost some things in it,” says Gatson about desegregation. “We gained some things and we lost some.” Boudreaux agrees. “Once things were fully integrated, people had choices,” she says. “Where people couldn’t go to Gaido’s before, they could go to Gaido’s now. The parks were opened up; they had places they could go. Those [Black-owned] businesses were not as popular as they used to be.”

Above all, the authors hope their efforts honor the legacies of Black Galvestonians who strengthened their community during times of oppression. “Nowadays, we’re going to college and getting business degrees,” says Gatson. “They [African American business owners] didn’t have all of that. They made it work. They figured it out. And they really left something to be remembered. They left a map to follow. That’s exactly what I’d like for you to know: They left the map. We just need to pull it out.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Texas Cookbooks

- Galveston