This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In Marfa, nothing fractures the vastness of land and sky. Among the towns scattered across the Big Bend region—Alpine, Marathon, Terlingua, Shafter, and Fort Davis—none is as far removed from mountainous peaks as Marfa. The Cuesta del Burro Mountains to the south and the Davis Mountains to the north seem, from their distance, like vaporous mirages. Still, flatness never had this much character. The air is gentle on the lungs, the plateau is cactus-spiked and well-trodden by antelope, and the starlit evenings are a communion with heaven. Marfa is a land for those who are spare of words and who wish to keep their distance. Tourists visit to wander through the region where Giant was filmed, to stroll through the Spanish-style Paisano Hotel, and to search the sky at night for the bizarre Marfa lights. But space is the adhesive that holds Marfans to their community. It is a reverence for this wide-open space, if nothing else, that the great minimalist sculptor Donald Judd had in common with his neighbors. For Judd’s visionary artwork, however unconventional it might appear, ultimately seems perfectly placed under the endless West Texas sky.

After dying of lymphoma at age 65 this past February, Donald Judd was buried at his 45,000-acre ranch, some fifty miles south of Marfa. The Missouri-born Judd first laid eyes on the town in 1946, while on a bus bound for California. Twenty-five years later, at the height of a fabulous (if controversial) career, the internationally celebrated artist packed his bags, said good-bye to New York, and moved permanently to Marfa.

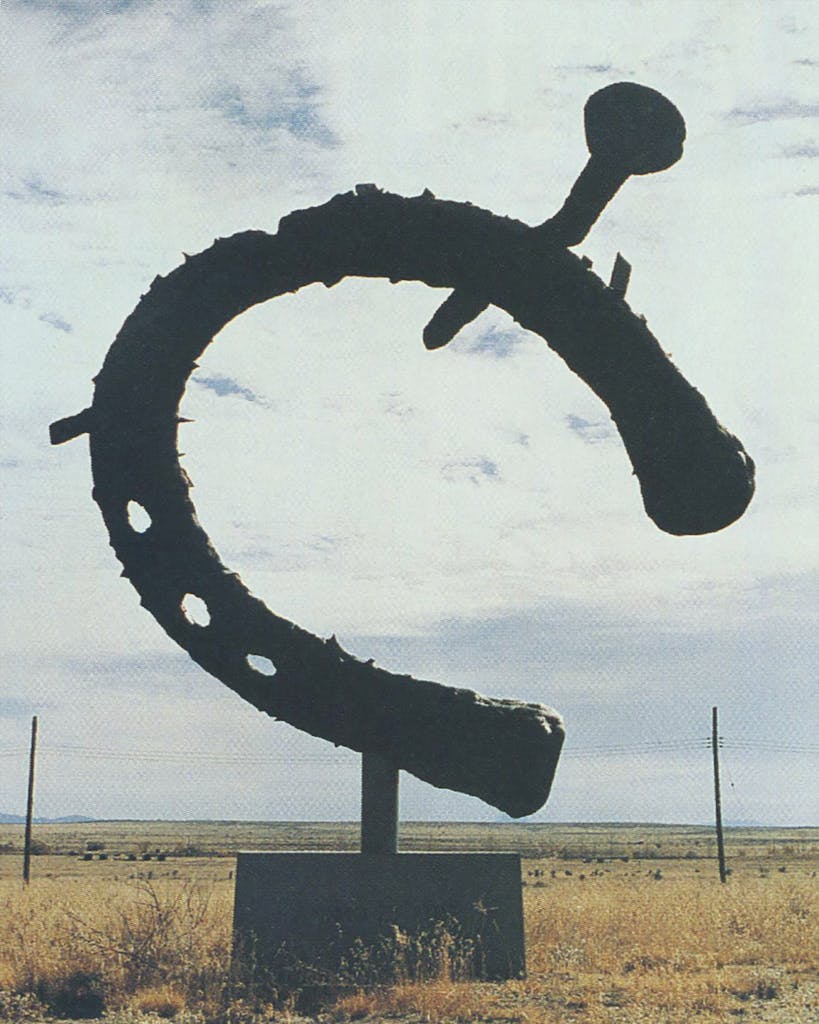

Judd left New York City because he loathed its claustrophobic feeling, its art sycophants, and its museum directors who, he felt, were clueless when it came to his precise and elegant works. He also moved to Marfa to work. In Marfa, Judd pursued, with a perfectionist’s deliberate pace, the art that won him international renown: sleek freestanding metal and plexiglass sculptures, with emphasis on industrial precision; spare modernist furniture; and coolly dignified architecture ranging from gallery interiors to stock tanks. Though he produced paintings, sculptures, and architectural projects in venues as scattered as Manhattan, Basel, Switzerland, and Cologne, Germany, it was Judd’s contemporary artwork in Giant country that the New York Times labeled “among the largest and most beautiful in the world.” What Donald Judd left behind in Marfa amounts to a tremendous collection of artistic treasures, ranging from his own paintings and sculptures to beautiful Navajo blankets, avant-garde works from Iceland and Korea, and early twentieth-century furniture. The artist’s work is carefully exhibited in several of the seventeen buildings he bought and restored, as well as throughout the 350-acre Fort D. A. Russell at the edge of town. Some of the exhibits have been and continue to be open to the public; the rest of Judd’s art is expected to be available for viewing after Judd’s estate has been sorted out. Judd’s collection provides a rich cultural addition to the many places to visit on an extended West Texas weekend, which might include hiking through Big Bend National Park, stargazing at the McDonald Observatory, checking out the country acts at Terlingua’s Starlight Theatre Restaurant and Bar, and availing oneself of the creature comforts at the Holland Hotel in Alpine and the Gage Hotel in Marathon.

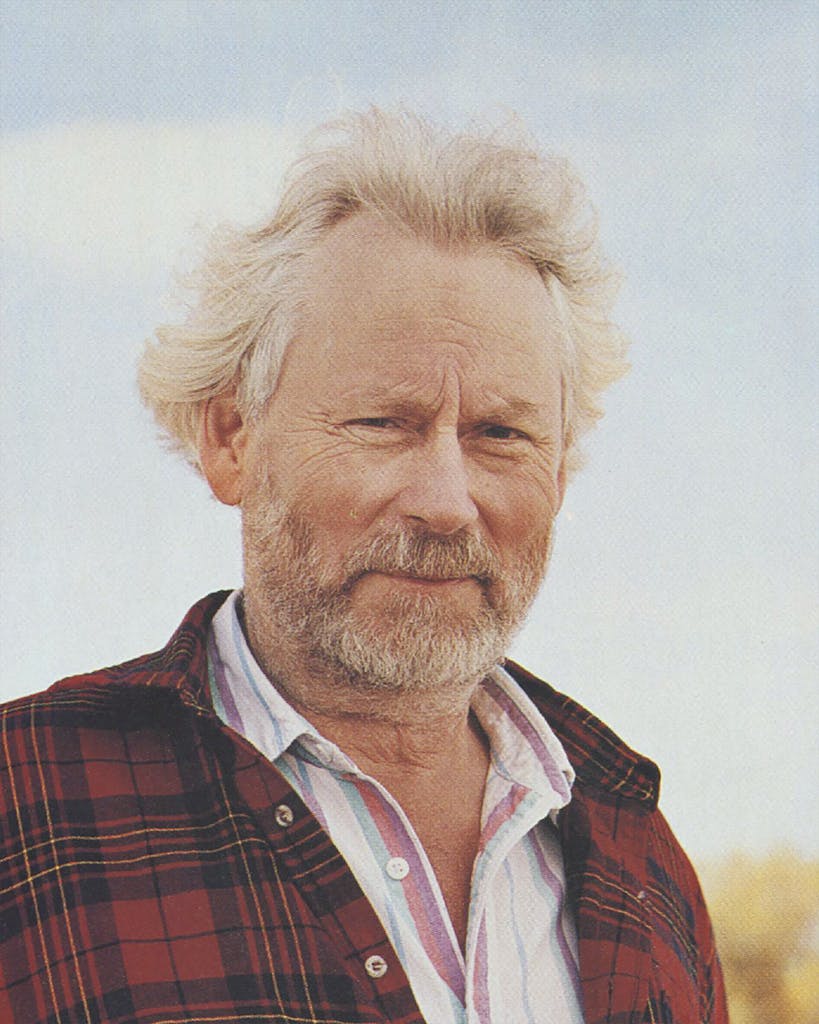

As the following pages attest, Dallas-based photographer Laura Wilson had unprecedented access to the reclusive sculptor’s world. This was no small feat, as Wilson learned when she first visited Judd last November. “He was ornery, testy, and wary of people, a very withdrawn man who felt uncomfortable being photographed,” she says. Judd’s wariness evaporated after Wilson gave him one of her photography books depicting a ninety-year-old West Texas rancher. The following day, he showed up early for the shooting and allowed Wilson to stay for a week.

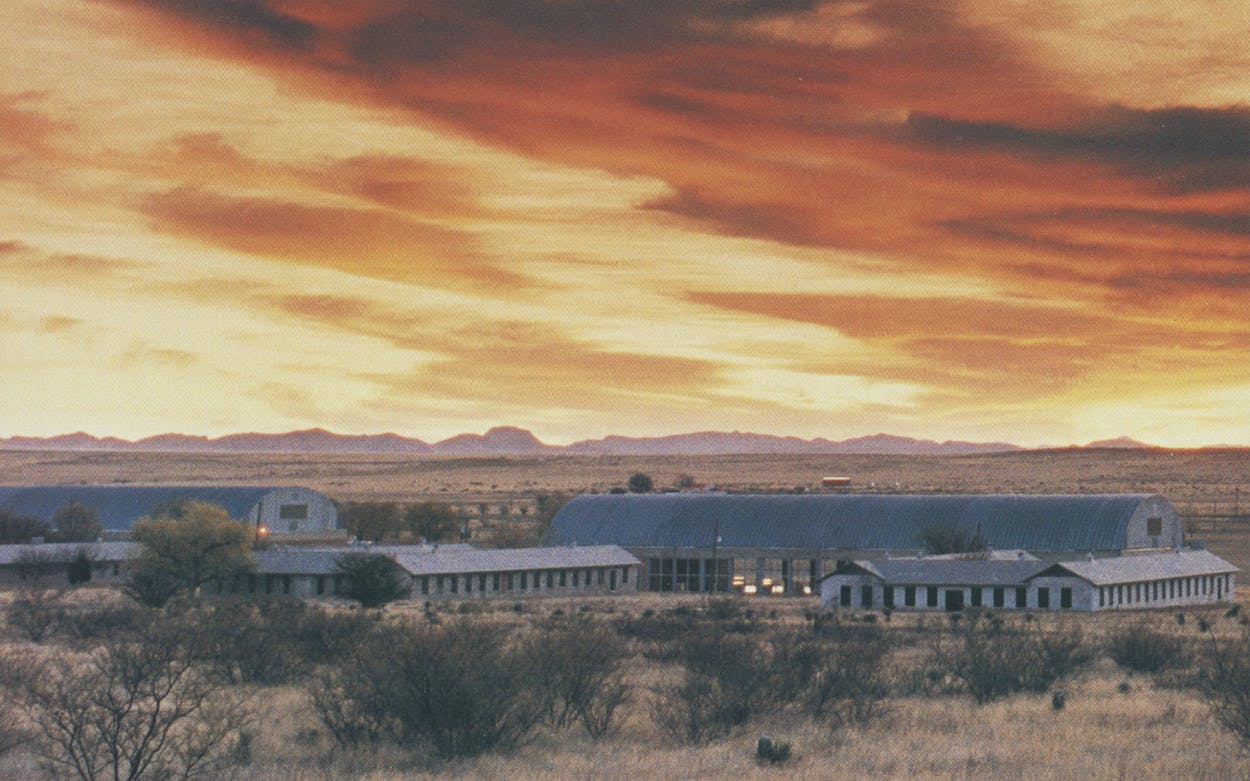

Judd’s most striking works can be seen by any visitor. He converted Fort D. A. Russell, a former military post and German POW camp, into a permanent exhibition space. What was once the gymnasium is now a metal-roofed arena and reception area, with long pinewood tables and even longer zenlike gravel floors. But the fort’s most astounding spectacles are the two artillery sheds with Quonset-style roofs that house one hundred aluminum box sculptures, placed in precise rows on each side of the sheds’ stark cement columns. By replacing the brick walls with windows, Judd has achieved a breathtaking juxtaposition of his sleek objects with the raggedy Marfa landscape. In an uptown gallery, the boxes might seem cold and stoic. But the effect is oddly yet undeniably harmonious when poised against the plateau. At dawn, the sculptures radiate bronze and copper; under the evening light, they maintain a dimly silver glow. At any time of day, however, the artillery sheds reflect an awe of space and proportion. It becomes immediately apparent why Donald Judd took refuge here.

Though he had a circle of friends in Marfa, Judd was not an easy man to get to know. One friend, Big Bend Sentinel editor Robert Halpern, observes, “Don was a very shy man, as well as a very purposeful artist. So a lot of folks viewed his shyness and his single-mindedness and misinterpreted him as being standoffish.” It did not help matters that Judd plastered the windows of one of his buildings, the old Marfa Bank, with butcher paper to ward off the curious or that he maintained a long-running feud with his next-door neighbor, whose ice-making machine Judd found infuriatingly noisy. To this day, many in the region know Donald Judd only as the man who bought the popular Kingston Hot Springs and promptly closed them to the public.

The sculptor’s generosity was real but measured. Every October, Judd threw an expensive weekend-long party that was well attended by Marfans. Yet he was a reserved host and shied away from the meeting and greeting. To the townsfolk, Judd was a wealthy landowner, but he had two additional strikes against him: He was an outsider, and his artwork was forbidding to the average resident. Halpern believes that most of the local Judd critics “never took the time to see his work.” Some of those who did gained a new outlook on the man, while others shook their heads in bewilderment. Both the artist and his art had to be taken on their own terms.

Because of his low profile, few Marfans knew how deeply Judd cared about their town. He was an active follower of local issues and enjoyed talking Marfa politics with his friends. Deeply committed to preserving the area’s environment, Judd considered hiring an attorney to fight the City of El Paso when the latter bought a farm in nearby Valentine that sat over a precious aquifer. He purchased the 45,000-acre Ayala de Chinati Ranch in large part to rule out the possibility of development in the Chinati Mountains. Among the numerous projects he contemplated were plans to boost the Marfa economy, such as marketing Highland Hereford beef, bottling and selling the local water, propagating chemical-free agricultural products, and renovating several vacant homes for use as a subsidized retirement community.

Fortunately, Judd’s Chinati Foundation not only remains in operation but continues to develop new artistic projects. His children, Flavin and Rainer Judd, say that many more of Judd’s art objects exhibited and stored throughout the world will be moved to Marfa, making this dusty town an astonishing repository of modern art. Though such additions would give a boost to Marfa’s hobbled economy and prompt warmer sentiments among local Judd detractors, no one need fear that the money of Donald Judd will be used to clutter the town’s landscape. This is, after all, minimalist country.

The Chinati Foundation, located at Fort D. A. Russell on the southern end of town, is available for touring every Thursday, Friday, and Saturday from 1 p.m. until 5 p.m. However, the friendly and knowledgeable foundation staff members are willing to conduct tours during off-hours as well, if notice is given by calling the foundation at (915) 729-4362 and leaving a message. The tour also extends to the Chamberlain exhibit hall in Marfa proper, across the street from the old Marfa Bank. The Chinati Foundation staff members will be glad to point out the other Judd properties, which for now are closed to the public.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Donald Judd

- Marfa