Betty Rubble’s hands are sheathed in gloves of shiny black leather as she pinches Wilma Flintstone’s nipple. Fred Flintstone looks on, his tongue lolling lasciviously out of the side of his cartoon mouth. Pebbles Flintstone, all grown up in skintight dominatrix gear topped off by an Iron Cross necklace, dangles a whip above the head of Dino. The legs and tail of the cuddly pet dinosaur are bound with spikes and chains, a ball gag crammed in his mouth. Dino’s eyes are rolled back in a fever of pain and ecstasy.

This depraved, defiantly copyright-infringing masterwork stood at least ten feet tall inside the original location of Austin rock club Emo’s, where I first encountered it in 1996 on one of my earliest trips into the city. A friend of mine—who’d already lived in Austin for a whole year before me, and was thus already several degrees cooler—caught me staring at it, naturally. “That’s an original Kozik,” he said with blasé, hip authority. Oh sure, I nodded. A Kozik.

By the time I myself moved to Austin in 1997, I also knew how to spot a Kozik. It was hard not to. Frank Kozik’s posters screamed at you from across a crowded room: horny devils and scantily dressed women, Nazis and clowns, giant insects and two-headed dogs all rendered in bold, fluorescent Day-Glo and awash in drugs and death. If you wandered into any punk venue or record store during the nineties, you were likely to see a Kozik staring maniacally from its walls. As his work spread beyond the Austin punk underground that had fostered it, with huge bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Beastie Boys, and Green Day commissioning wild, silk-screened prints for their own tours and shows, Kozik’s art became intertwined with an entire decade of music, his imagery as indelibly seared into the memories of Generation X as that Flintstones S&M fantasy remains on my own.

Frank Kozik died May 7 at the age of 61, according to his wife, Sharon. In a statement posted to Kozik’s various social media accounts, Sharon said, “Frank was a man larger than himself, an icon in each of the genres he worked in. He dramatically changed every industry he was a part of. He was a creative force of nature. We are so beyond lucky and honored to have been part of his journey, and he will be missed beyond what words could ever express.”

“His forceful presence will be missed by all who knew him,” she added. “His legacy, like all great masters, will live on through his art and our memories of him.”

Granted, Kozik had often balked at the idea that he was a master of anything—and certainly not art. “I’ve always done advertising; I’m not an artist. I didn’t invent anything new,” he told Texas Monthly in 2001. “The thing I do is in support of something else. There’s no great message behind my work. I don’t have any standard technique. I’m not putting my raw emotions on canvas in startlingly beautiful form to convey an emotive state. That’s art. I make posters.” In 1997, he summed up his work for the Austin Chronicle thusly: “Some people think it’s the greatest f—ing pop art deconstructionist cultural trip in the world. Other people say it’s pure f—ing bullshit.”

It was an attitude that was ideally suited for Kozik’s era, when various grunge, indie, and other so-called “alternative” artists were defining themselves through their own stances of amused detachment, deflating the pretense and self-importance of rock stardom. Kozik had likewise grown up feeling like an outsider. He was born and raised in Spain by a family of real-deal fascists who hung a portrait of Hitler in their house (the “Rosebud” that explains his work’s Nazi fixations). Kozik moved to California on his own when he was just sixteen, where he soon ran afoul of the law. He ended up joining the Air Force to escape prison time and landed in Austin in 1980, an eighteen-year-old sergeant stationed at the long-defunct Bergstrom Air Force Base. He quickly found himself swept up in the local punk scene that revolved around venues like Club Foot, regularly attending shows by groups like Dicks, Scratch Acid, and Butthole Surfers. “It changed my life,” he would later recall for Texas Monthly.

Kozik didn’t play any instruments, so he had to find other ways to be cool. He’d already been exchanging “mail art”—a practice now largely lost to the internet—with a Portland collective that called itself the Art Maggots. When a couple of the Maggots relocated to Austin, Kozik said, he began “hanging out with them, drawing comics and nonsense guerrilla street art stuff” that they would then Xerox and post on light poles around town. These eventually caught the eye of local bands and promoters, who commissioned Kozik to make the occasional flyer. Then, as Kozik explained in his 1996 collection Man’s Ruin: The Posters & Art of Frank Kozik, he had the good fortune to meet Brad First, who hired Kozik as a doorman at his newly opened punk venue, the Cave Club.

“Brad was the first club owner I had ever run across that valued posters, and not only was he willing to pay for them, but he actually wanted them large format and in two colors!” Kozik wrote. “I was in heaven, and cranked out as many as he would let me.”

His reputation grew as quickly as his output. Soon every band in town wanted “a Kozik.” He was able to parlay his new cachet into a job doing graphic design for a local T-shirt company, and he supported himself doing other “less than cool” commercial work. Then he had another stroke of luck: A Hollywood gallery owner named Debi Jacobson sent her protege, Robert Weiss, down to Austin to meet with the Armadillo Art Squad, who were well-known in the fine art world for their posters for the Armadillo World Headquarters. When Weiss arrived, however, he found that the most prominent members of the Squad were absent. There was only Frank Kozik, who happened to share a small corner of their studio. Kozik gave a bunch of his prints to Weiss, who took them back to Jacobson. And the next thing he knew, Kozik had his first gallery show in L.A., and a well-heeled patron gave him $10,000 to set up his very own silkscreen press, which he used to make his first large-format silk-screen rock poster. “And that was like the magic combination, because people really liked that,” he recalled to the Austin Chronicle.

Among those who really liked it was Rolling Stone, which devoted three pages of its December 1993 issue to Kozik’s work as “the new rock-poster genius.” By then, Kozik had been doing steady work for bigger and bigger groups, fine-tuning an aesthetic that married the mawkish with the macabre in a way that often had little to do with the actual music—or made little sense at all, really. A poster for a Helmet and L7 show, for example, was built around a blown-up photo of Lee Harvey Oswald at the moment he was felled by Jack Ruby’s bullet, a microphone thrust in Oswald’s face. A print for a Chicago gig by Babes in Toyland and Killdozer finds a trio of adorable bunnies stacking wooden blocks that spell out “PCP” atop Charlie Manson’s head. These works were “psychedelic” in a bad-trip sort of way, a playfully hellish vision that suggested Hanna-Barbera by way of Hieronymus Bosch. “I hit on a formula early where, if it was a massively evil band, I’ll do something that’s insanely cute, and that’d make it weird,” as he described it in 2018. “Conversely, if it’s something more normal, I’d insert some secret dark element,” he said.

By 1993, Kozik had also left Austin behind, decamping to San Francisco in 1991 after deciding that Austin’s fabled velvet rut had left him too complacent. “I got fat. I didn’t have a bank account,” he told Texas Monthly. “I’d paddle around in a pair of shorts. It sounds idyllic until you actually start living that way. I thought, ‘This is not the fantasy I had of being an adult when I was a kid.’ I knew I had to do something else. I needed to move to a big city and see if my bullshit would float in the real world.”

It did. Kozik flourished in San Francisco, landing ad campaigns with big companies like Nike and getting contracts to work in Europe and Japan. He designed album covers for groups like Melvins, The Offspring, and Queens of the Stone Age. He directed a music video for Soundgarden. In 1994, Kozik launched his very own record label, Man’s Ruin, on which he released hundreds of albums and singles by artists that he liked, such as High on Fire, Unsane, and Turbonegro. Kozik personally designed the sleeve art for every release, and he split the proceeds with the bands fifty-fifty. Man’s Ruin folded in 2001, citing problems with its distributor and the looming ruin of the independent record industry. By then, Kozik was long done with making posters; after Man’s Ruin, he was more or less done with music.

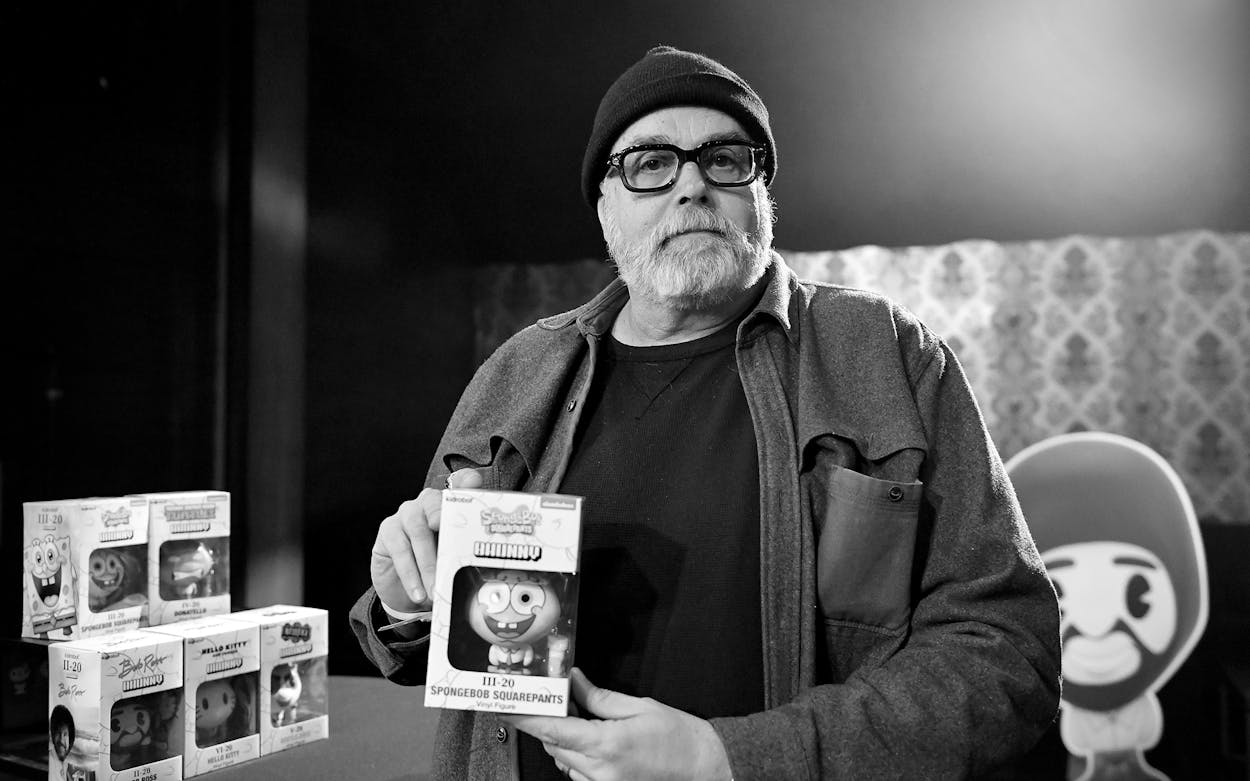

Kozik found his second calling in the world of toys and collectibles, eventually rising to become chief creative officer of the Boulder-based Kidrobot, where he applied his cute-yet-evil aesthetic to designing vinyl figures like the mustachioed, cigarette-smoking Labbit, a character that had first appeared in his posters. Under his direction, Kidrobot landed huge licensing deals with heavy hitters like Marvel and The Simpsons, while Kozik pushed the boundaries of the art form by making toys based on the works of Andy Warhol as well as his own bizarro imagination.

Like Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Kozik was a pop artist who dealt in appropriated imagery—you might even say stolen—and he often spoke of this technique in crass terms of commercialization and industrialization. “All I do is consume the mountain of pap that surrounds us and extrude it in what I think is a more palatable form,” Kozik wrote in the introduction to Man’s Ruin, adding that he didn’t even like to call himself an “artist,” he said. “Personally I prefer the term ‘graphic artist,’ or poster guy, or whatever.”

Or whatever. Kozik was unfailingly self-deprecating, even dismissive about his own work, but there’s no denying that it had the same impact of all great art, which is measured not in how innovative it is but in how it makes you feel. His influence is felt not only on the many other designers and “poster guys” who have continued to ape his style, but on anyone who has ever come across one of Kozik’s creations and found themselves unsettled or repulsed, piqued or titillated—and feeling as though they’ve been let in on some sly cosmic joke. Once you’ve seen a Kozik, you’ll never forget it.

- More About:

- Art

- Obituaries