Dallas-born photographer Gray Malin’s job sure looks like a lot of fun. He has spoken to interviewers of a professional schedule of “one week at home, one week on the road,” with the biweekly trips typically involving hanging out of a doorless helicopter above one or another of the world’s most beautiful beaches, snapping pictures. His seventh photo book, Coastal, released this May, presents a selection of the images he’s gathered on such excursions, from Hawaii and Australia to Michigan, where Malin spent childhood summers, and Southern California, where he now lives with his family.

The slogan of Malin’s thriving company, which sells printed puzzles, beach towels, rugs, and furniture in addition to framed photos and coffee-table art books, is “Make every day a getaway.” If such a thing is possible in the professional realm, Malin has apparently pulled it off. That sense of the photographer himself having outsmarted the daily grind is central to his work’s wide appeal, which goes far beyond the art market and into the realms of branded design and home decor, where it’s on the cutting edge of twenty-first century kitsch.

For those purists who prefer to conceive of art as a creative mind’s struggle for self-articulation, or as an ever-developing conversation through the generations among humanity, our expressive materials, and our objects of fascination, there’s something astonishing in the present ubiquity of Malin’s aerial beach views and staged photos of dogs in upscale vacation locales (e.g. his Dogs of Aspen, Dogs of Palm Beach, and Dogs at the Beverly Hills Hotel photo series). But there’s not too much mystery to their charms.

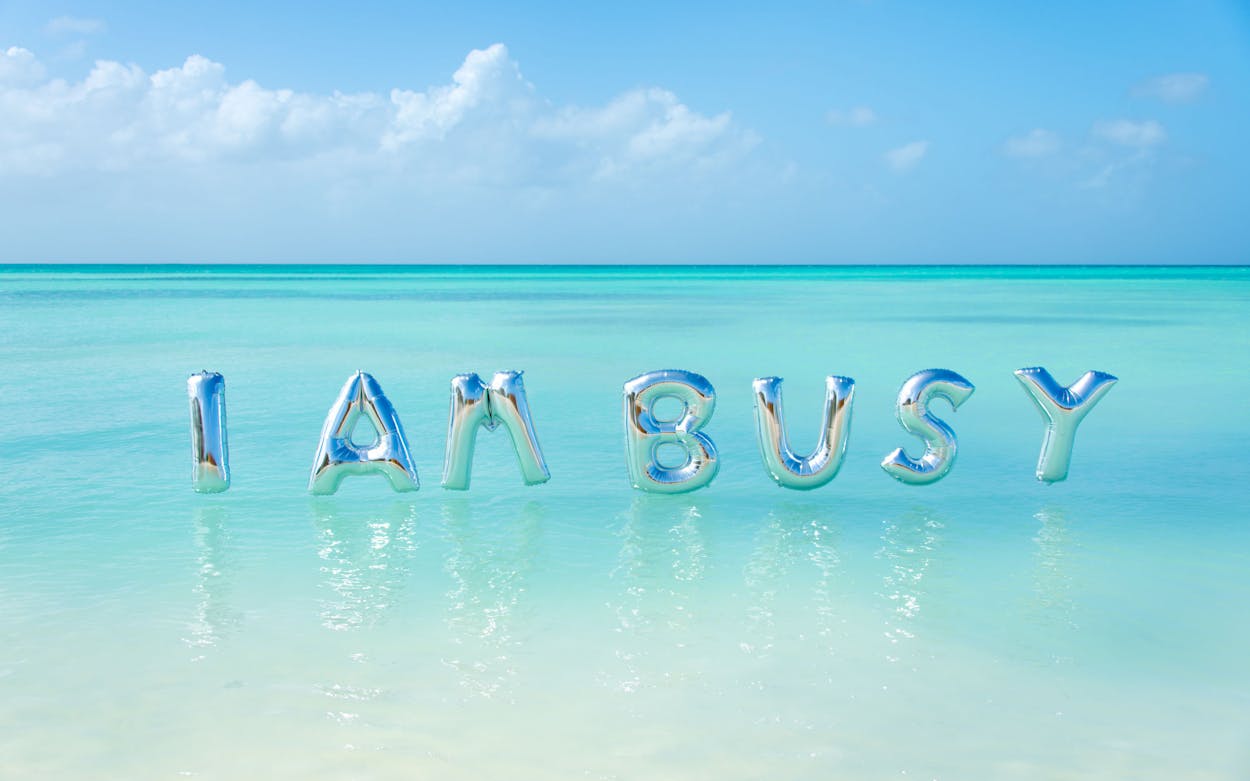

On the simplest level, they remind us of a nice trip we once took or of a favorite place we like to visit. More abstractly, Malin’s photos, serving trays, note card sets, passport cases, pillows, coasters, backgammon sets, goals journals, et cetera invite us to momentarily exist in that parallel, half-imaginary, fugue-state reality we sometimes call vacation, where all the tensions of actual life need not apply. This escapist ethos is perhaps best captured in one of Malin’s most enduring staged images—seven gray balloons floating above an aquamarine coastal view spelling out “I AM BUSY.”

In more subtle ways, Malin’s helicopter photography builds on the same vision. His beach images tend to emphasize the endless line where surf meets sand, at the same time showing other parallel lines formed by high and low tides, vegetation, beach umbrellas and lounge chairs, wave breaks, and deepening water. “Each destination has its own unique idiosyncrasies but the beach itself is a symbol of happiness that is universally joyful, nostalgic, and calming,” Malin writes in his introduction to Coastal. “It’s a subject matter that everyone can relate to and share in beautiful moments and summer memories. Capturing this feeling in my images is the best part of my work and what I’ve built my brand upon.”

Malin grew up around photography. His mother was a former interior design editor for Mademoiselle and Glamour who remained involved in producing magazine photo shoots after moving to Dallas. In a New York Times profile, Malin spoke of coming along on photo shoots as a kid, doing his homework in a corner. He studied photography in high school—he attended tony private schools Lamplighter and the Episcopal School of Dallas, near his home community of Preston Hollow—and presciently double majored in photography and marketing when he left Texas to attend Emerson College, in Massachusetts.

The beaches of Port Aransas, Galveston, and South Padre don’t make appearances in Coastal—understandably so, as even a state with as much pride as Texas tends to not bother making the case for its coastline being among the world’s most desirable. In many ways, though, Malin does owe his breakthrough as a photographer to travels in his home state.

In 2010 Malin was living in L.A., having recently quit a job in the film industry to pursue his passion, and selling photos for $65 a pop at a flea market in West Hollywood. On a family trip to West Texas, he took a few pictures of Ballroom Marfa’s Prada Marfa installation on a remote stretch of U.S. 90, figuring he’d show them in a photography class he was taking. His teacher loved the images and encouraged him to take more. Malin did, and he soon found that they were hot sellers. He’d found his first viral subject matter—on vacation.

Malin’s inspiration for aerial photography, too, came from taking a trip to Las Vegas in 2011 and shooting a photo from a high hotel window overlooking the pool. Indeed, through all Malin’s beach photography—a mainstay of his previous photo books as well, including the titles Beaches, Escape, and Italy—one can trace that same easy sense of ownership and idle curiosity, that of a just-arrived penthouse guest looking down and thinking, “Why not? Perhaps I’ll have a swim.”

Malin’s prints go great in a hotel or an Airbnb, so it’s perhaps not surprising to learn that he began his rise selling his wares on the website One Kings Lane, an e-commerce outfit more geared toward home goods than art. (Malin has told D Magazine that he checks the website every morning when he wakes up.) His products can also make your own home feel a bit more like a hotel or a short-term rental. Hang one on your wall, and it’s like opening an airy window to a pleasant, vague, untroubled elsewhere, where the bed is always made and the cleaners have just been through.

The writer Milan Kundera, who passed away this week, defined kitsch as “a rosy veil thrown over reality”—a vision of the world in which whatever crap we put up with as a daily fact of life simply does not exist. It’s a critical view, but Kundera also acknowledged that there will always be a place for kitsch: “No matter how we scorn it, kitsch is an integral part of the human condition.”

The sorts of kitsch that Kundera focused on in his writing had to do with the political utopianism and nationalism of the Cold War era. Our age is different, with our desires transformed by image-based social media, unfettered travel, and global consumerism, even as we privately fret about environmental destruction and runaway inequality. It’s hard to imagine a decorative aesthetic that rides the waves of our contemporary anxieties and thirsts more compellingly than Malin’s endless-summer dream.

If you want evidence of the importance of the fantasies Malin sells to our present moment, consider that his framing partner was deemed an “essential business” during COVID-19, allowing it to sell during the shutdown. And sell Malin did—he reports that his two-sided puzzles in particular were difficult to keep in stock. The less busy we were, the more we needed some occupation for our hands and minds. In those empty, uncertain days of homebound stasis, Malin’s alluring visions of permanent vacation kept us going.

- More About:

- Art