When the Rams of Huston-Tillotson University take the field Saturday in East Austin, the baseball team members will be wearing uniforms resembling those worn by the Negro leagues’ Austin Black Senators. The tribute jerseys will coincide with MLB’s Jackie Robinson Day, which the league celebrates every year to commemorate the day Robinson broke professional baseball’s color line in 1947.

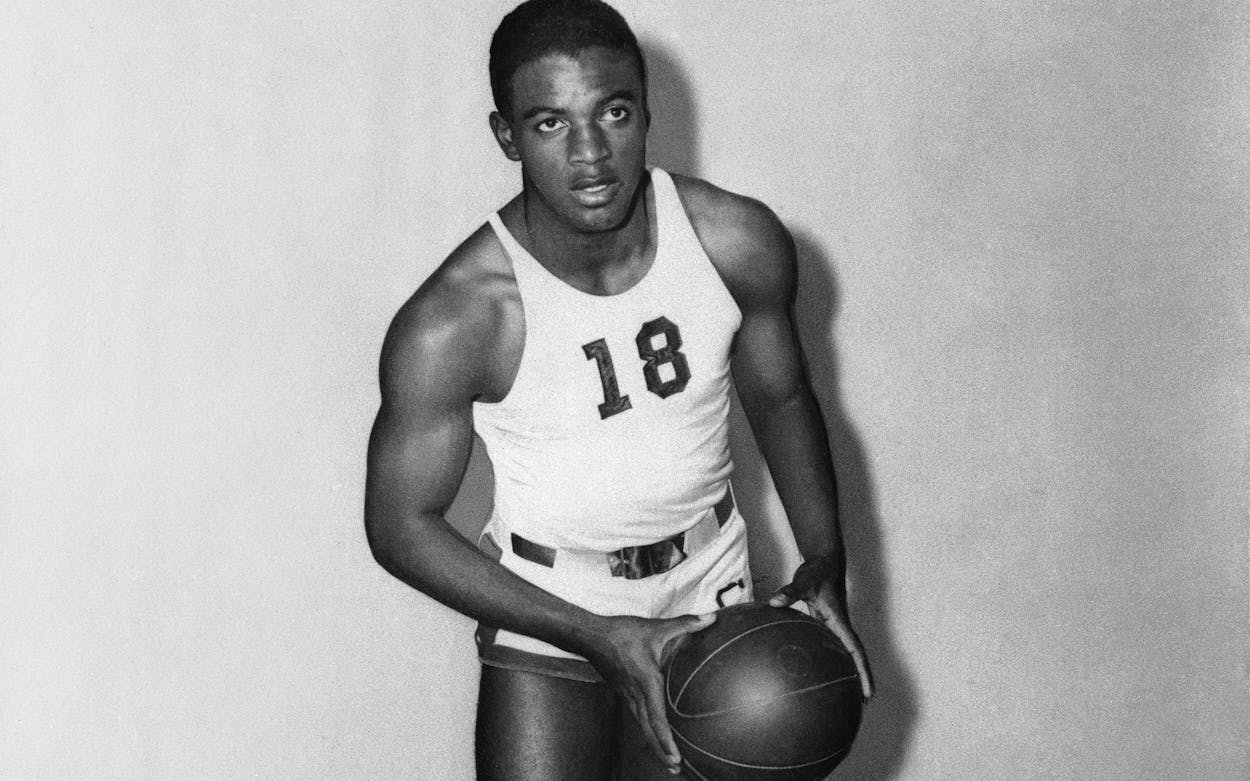

Huston-Tillotson has more reason than most historically Black colleges and universities to feel a connection to Robinson. Only months before the Hall of Famer began his professional baseball career, he served as the head basketball coach at one of HT’s forerunner institutions in Austin, Samuel Huston College, during the 1944–45 season. (Named for the benefactor who had donated campus land years earlier, Samuel Huston College merged with Tillotson College in 1952.)

Thomas Henderson, HT’s basketball coach for the past ten seasons, notes that many fans of Robinson’s career timeline believe he went directly to baseball after completing his service with the U.S. Army. “There’s a gap,” Henderson said. “That gap is Huston.”

The NAIA Rams’ baseball game on April 15 will be played at the school’s home ballpark, built by the city in 1949 a few miles northeast of campus as a “separate but equal” facility for Black residents. It’s named Downs Field for Karl Downs, the Samuel Huston alum who became the school’s president at age 31 in 1943.

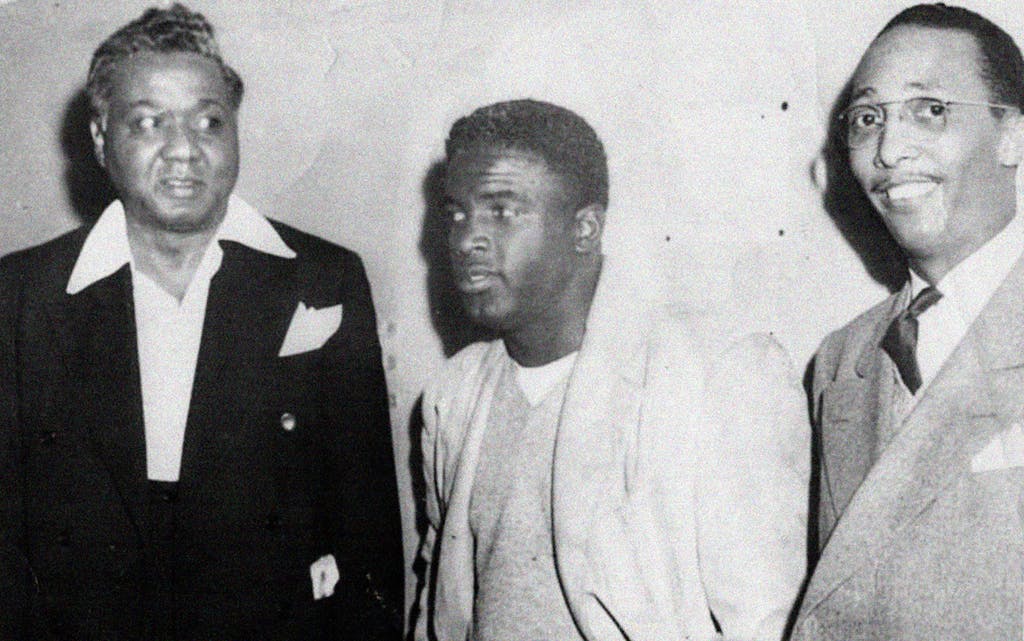

Karl Downs is the reason why Jackie Robinson became a college basketball coach in Texas.

Downs was born in Abilene in 1912 and graduated from high school in Waco before becoming a Methodist minister. He was assigned to a church in Pasadena, California, and came to know a young man only six and a half years his junior—Jack Roosevelt Robinson. Robinson, a gifted athlete, had no father figure in his life. Downs filled that void and helped steer Robinson toward successful multisport careers at Pasadena Junior College and UCLA.

The California preacher was also active in social causes. In 1943, Downs published Meet the Negro, a book meant to honor and commemorate the accomplishments of Black Americans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Shortly after Downs returned to Texas to take over Samuel Huston College, Second Lieutenant Robinson was departing Fort Hood, just north of Austin. As has been well chronicled, Robinson faced a court-martial after refusing to sit in the back of a military bus, but an all-white panel voted to acquit him of insubordination charges.

In November 1944, fresh off an honorable discharge from the Army, Robinson was looking for work. Downs, with less than a year under his belt as university president, was looking for a basketball coach for the school’s highest-profile sport; Samuel Huston didn’t field a football team then, and Huston-Tillotson doesn’t today. He asked Robinson to fill the position. “I knew that Karl would have done anything for me, so I couldn’t turn him down,” Robinson wrote in his autobiography, I Never Had It Made.

Little is known about the Samuel Huston Dragons’ one season on the hardwood under Coach Robinson. Austin’s newspapers didn’t cover the team closely. There doesn’t appear to be a 1944–45 Samuel Huston yearbook on HT’s campus, and that edition isn’t included in the school’s digital yearbook collection. According to Arnold Rampersad’s biography of Robinson, the Dragons played that season in the Southwestern Athletic Conference with familiar names like Grambling State, Prairie View A&M, and Southern University, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Rampersad noted that under Robinson, Samuel Huston scored a 61–59 upset over Bishop College, the defending league champion.

Another reference to Robinson’s time as coach came from the 2015 New York Times obituary of Marques Haynes, the Harlem Globetrotters ball-handling wizard. Haynes played for Langston University, in Oklahoma, and he said he saw Robinson’s team beaten in the SWAC postseason tournament by Southern—which inappropriately ran up the score, as Haynes saw it.

The Austin Chronicle spoke in 2014 to one of Robinson’s players, Roland Harden. “He worked us hard and taught us a lot about the fundamentals of basketball,” Harden said. “He was stern as far as the sport was concerned, and otherwise a good, friendly guy—and supremely talented. He’d get out and work with us, and bump us around. He was a much better player than anybody on our squad.”

Robinson left Austin to join the Negro leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs for the 1945 season. Harold “Pea Vine” Adanandus, the basketball team’s trainer that season, recalled his reaction to the news for a 1997 article in the Austin American-Statesman: “I said, ‘Well, Jackie, I didn’t even know you played baseball. And he said, ‘Yeah, I play a little.’ ”

Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ president and general manager, signed Robinson that October. Several months later, Jackie Robinson and Rachel Isum were married in Los Angeles, with Downs officiating. Robinson spent the ’46 season with Brooklyn’s top farm club in Montreal. Then came the historic 1947 campaign, with Robinson chosen as the major leagues’ first Rookie of the Year.

As the season neared its conclusion, Robinson made sure Downs was present when the team recognized him with the original Jackie Robinson Day in Brooklyn that September. While there, Downs was hospitalized with severe stomach pains. Against the wishes of the Robinsons, Downs insisted on returning to Austin and getting back to work on campus.

In Texas, Downs’s health continued to deteriorate. He died in February 1948 at 35, leaving behind his wife, Marion, and young daughter, Karleen. In his autobiography, Robinson recalled the end: “Karl went to a segregated hospital to be operated on. As he was being wheeled back from the recovery room, complications set in. Rather than returning his black patient to the operating room or to a recovery room to be closely watched, the doctor in charge let him go to the segregated ward where he died. We believe Karl would not have died if he had received proper care.”

Today, Huston-Tillotson occupies a rectangle of 23 acres a few blocks east of Interstate 35, with an enrollment of 1,025 students. Downs’s last name occupies a prominent spot on campus, where it makes up half of the school library’s title, along with the surname of former Tillotson College president William H. Jones. And there’s the city’s Downs Field, with a modest seating capacity in covered wooden stands. Before Huston-Tillotson’s ball game there on Jackie Robinson Day, organizers have planned a youth baseball clinic, a market featuring Black-owned small businesses, and slam poetry performances.

A few miles east of Downs Field is a small residential street named for Jackie Robinson.

But on HT’s campus, there’s no marker to inform students and visitors that one of the most celebrated sportsmen in U.S. history spent a season as the school’s basketball coach; he also served on the university’s board of trustees during the late sixties and early seventies. Robinson’s name is nowhere to be found in Mary E. Branch Gym, home to Huston-Tillotson basketball since 1952.

Melva K. Williams, who became Huston-Tillotson’s president last August, said tangible recognition of Robinson on campus is “absolutely something that we would be thinking about.” She added: “It is our responsibility to maintain the legacy of both [Samuel Huston College and Tillotson College]. We’re about to start master planning and strategic planning, so those will be conversations that will emerge.” Jared Lyons, the school’s interim athletic director, and Henderson, the basketball coach, both said that every Rams athletic recruit, no matter the sport, is told of Robinson’s legacy with the school.

“It’s important to me,” Henderson said. “Holding this job, I stand on his shoulders.”

- More About:

- Sports

- MLB

- Basketball

- Austin