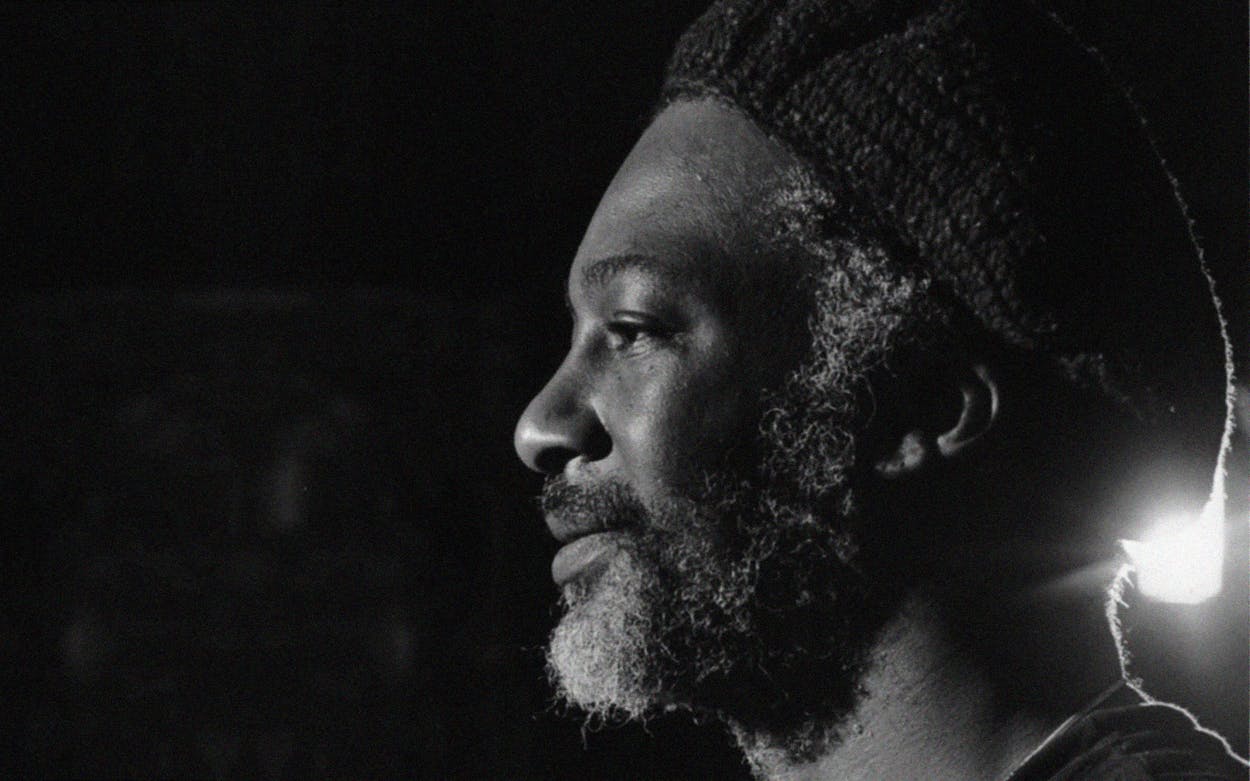

It’s difficult to overstate Jesse Lott’s importance to the visual arts world of Houston. Lott has been called a “shaman-like presence,” a “philosopher king,” and “the John Henry of the art community.” The unique, expressive idiom he developed and his institutional legacy are enduring icons of the city.

Lott passed away last week, according to a statement by Project Row Houses, the exhibition space and arts nonprofit that Lott cofounded in Houston’s Third Ward in 1993. Lott was eighty, and no cause of death was noted.

“His kind eyes, warm heart, and deep, slow laugh could soothe your soul, while his formidable intellect and fierce talent could trouble the waters when waters needed troubling,” Project Row Houses wrote in an Instagram post announcing his passing. “He found beauty in what others discarded, spoke truth to power, and took time to mentor untold numbers of Houston artists.”

Lott was born in Louisiana and moved to Houston as a boy. At age fourteen, he sold his first painting. He attended E. O. Smith Elementary School and Kashmere Gardens High School, where he played basketball and where he encountered John Biggers, the legendary muralist and founder of the art department at Texas Southern University (then known as Texas State University for Negroes). Biggers had recently traveled to Africa and was visiting Houston-area high schools in that era, encouraging artistically inclined youngsters to look to that continent for inspiration in their work.

Biggers became a mentor to Lott, inspiring him to attend college at his alma mater, the Hampton Institute in Virginia (now called Hampton University). Later Lott would also study at Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, where he came under the tutelage of renowned social realist painter and printmaker Charles White. Lott became involved in the Black Arts Movement sweeping the nation in the 1960s, and he brought that sense of wider purpose and community when he returned to Houston in 1974.

Lott became best known in his hometown for an approach to sculpture and collage he called “urban folk art” or “urban frontier art.” In the catalog for a 1977 exhibition, he described it: “The sculptural technique, represented here, is a combination of the natural resources of the urban community along with the skill of a trained artist and the attitude of the primitive.” His materials were often found on the street and of rugged, weather-beaten quality. His figures might be human or bestial, radiant or monstrous.

Often, Lott worked not only with found objects but also with the people he encountered around the Fifth Ward, employing neighborhood kids and others with little connection to the art world to help make his sculptures. Rick Lowe, another iconic Houston artist, told Texas Monthly: “He’s concerned with people who are making art as not an academic thing. It’s something that is somehow deeply connected and rooted in the spirit of the person. And so finding people on the street, people in the neighborhood, and introducing them to art and mentoring them, that’s where his mentorship to me really starts to shine the most.” All the same, Lott’s guidance has also been noted by a host of bigger-name artists, including Bert Long Jr., James Surls, Robert Pruitt, and Angelbert Metoyer.

Lott’s greatest legacy might turn out to be his cofounding, with Lowe and five other artists, of Project Row Houses. This once-blighted block of 22 shotgun shacks in the historically Black Third Ward has become a mecca for the exhibition and practice of “social sculpture”—that is to say, art that takes society as its material and tries to induce some purposeful change or growth—as well as various other styles of art made by Black and Latino artists and others from backgrounds typically underserved by museums.

As news of Lott’s passing spread this week, voices chimed in on social media to recall memories of Lott’s frequent presence at Project Row Houses, sharing a smile that was missing a few teeth and engaging younger artists in frequent games of dominoes. “Jesse Lott was a true giant in the art world, and to those of us fortunate enough to know him, he was also gentle, kind, and wise,” wrote the artist and curator Robert Hodge, a dynamic force in Houston’s younger generation. “Whenever he was invited, Jesse was always there, ready to engage in profound discussions about art and life.”

Celebrated artist Mel Chin, now based in North Carolina, who grew up with Lott, thought of their shared lifelong ambition to become artists: “Jesse and I were bonded in that pursuit and he was the solid ground that made any leap stronger. I returned many a time to our shared beginnings in the Fifth Ward of Houston, to seek him out and be rewarded by the possible sighting of a new concocted creature. I’d wait to be refreshed by his bluesy, poetic observations and then, in hushed asides, to commiserate on where to leap next.”

Younger audiences who missed out on Lott’s heyday have been treated to two small but remarkable career-spanning shows of his work in Houston in the past decade: a 2016 show at Art League Houston marking his Lifetime Achievement Award in the Visual Arts, and a 2021 two-person show with Travis Whitfield at the now-defunct Station Museum, coinciding with Lott’s appointment as Texas State Three-Dimensional Artist for the year. These shows revealed Lott’s work as ever-relevant, speaking to present-day concerns, aspirations, and aesthetic fascinations. The latter show also showcased Lott’s fascinating drawings.

One of Lott’s most widely appealing works, “Basketball Players” (1987), has become a sort of centerpiece of a key gallery in the Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s new Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, grounding the encyclopedic museum’s survey of modern and contemporary art with Lott’s acute folk sensibility. In the sculpture, one can recognize stylized versions of various famous participants in the 1986 NBA Finals, including Larry Bird and Hakeem Olajuwon. Outdoor public artworks of Lott’s can be seen today along the southeast Metro line at Scott Street and Elgin, and in front of the Sunnyside Health and Multi-Service Center (see video below), both in Houston.

“History books will be burned,” Lott told Texas Highways magazine a year ago. “History will be mistold. But the art is there to be interpreted by each person every time they look at it.” Lott’s art, alongside that of the many he mentored and influenced, seems likely to speak directly to future generations of the dreams and realities of the beautifully ruinous Houston he knew.

- More About:

- Art

- Obituaries