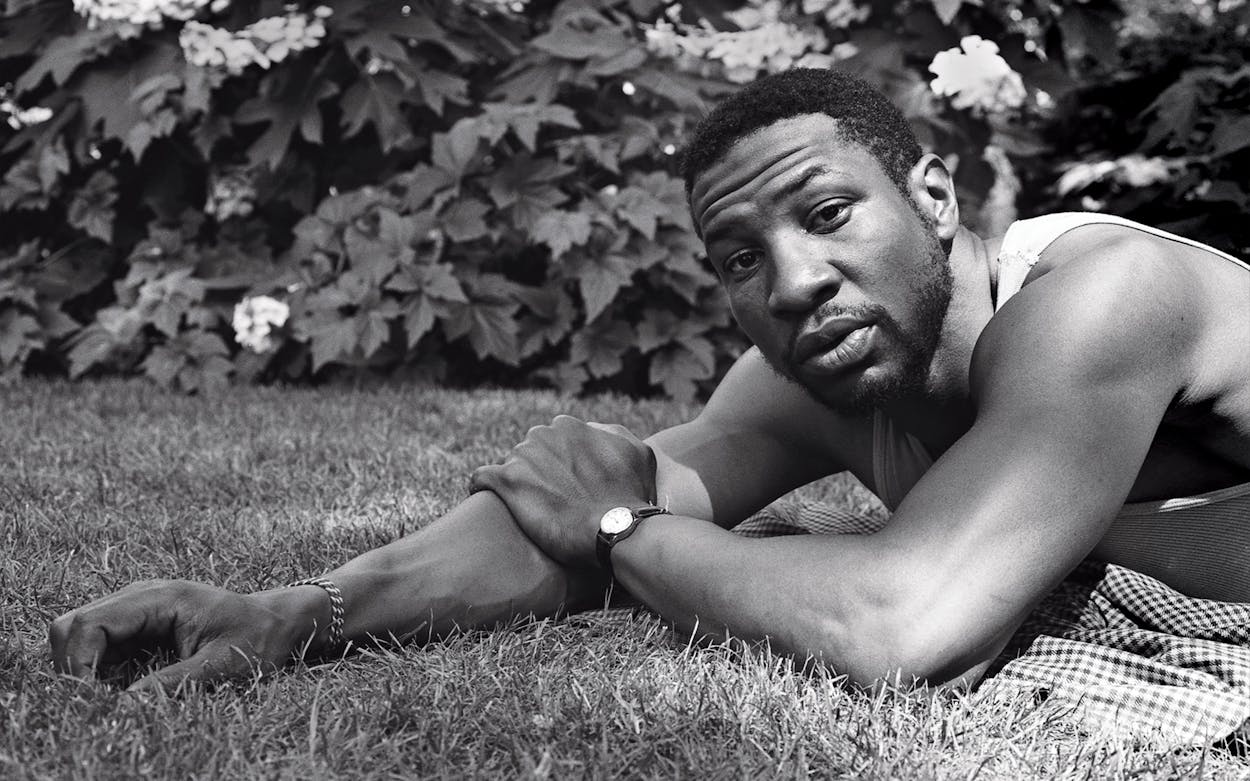

When he was growing up, actor Jonathan Majors found solace in the countryside at his grandmother’s farm, where he spent summers. That peace was harder to find in his hometown of Cedar Hill, and he sometimes got into trouble; he was kicked out of high school after being in a fight. Later on, after he’d reenrolled, a teacher introduced him to acting, which enraptured him. Majors went on to study acting in college, and in the final year of his MFA at Yale, he landed his first screen role, as gay rights activist Ken Jones in the ABC miniseries When We Rise. Majors, thirty, has since starred with Matthew McConaughey in White Boy Rick and stolen scenes in The Last Black Man in San Francisco. In HBO’s new horror series Lovecraft Country—produced by Jordan Peele (Get Out) and showrunner Misha Green (Underground)—he plays Atticus Freeman, a war veteran with a complex family legacy. An inventive take on the genre, the show, which premieres August 16, follows a Black community trying to survive in 1950s America.

Texas Monthly: Tell me about where you grew up.

Jonathan Majors: I grew up in the Dallas Metroplex. But I spent a lot of time in Waco and then in small towns down there with my grandma and then in Killeen and in Riesel. I’m also a military brat [Majors’s father was in the Air Force]. I was born in California and moved to Texas very, very young. Me, my siblings, and my mother and father lived in Georgetown, outside of Austin. Then we moved to the Metroplex—Cedar Hill, the Little Creek Apartments.

TM: Do you have good memories from that time?

JM: Apartment E8, that was the best place. There was a creek that ran behind the apartment. I spent so much time in that creek. When I was a boy, it felt like the creek would take you to the other side of the world. It was probably two miles in either direction.

TM: You’ve spoken before about being angry as a young Black man. Do you still have that anger?

JM: As a boy and even now, I am wont to melancholy. I do, probably once a day, experience a sincere heartbreak. The anger came from the inability to articulate my sadness. Which is what acting really gave me: the ability to articulate, with language, with nuance, with emotion, what I’m feeling. To give vibration to that heartache. That’s why I act: to articulate that feeling. Because I don’t believe that I’m the only one who experiences it. It’s a part of the human condition. Every script, every role, every character gives me an opportunity to articulate that. . . . Once it’s moved through the vessel, just moved through the spirit, it changes and shifts, and you can experience, as my mother would say, “an unspeakable joy.” And then that unspeakable joy can then be changed and altered into a damnable rage, an Old Testament type of wrath that can come through. And then that can fall back into melancholy. And then the joy will come back.

To be a Black man in America, you are born into the horror genre. You are not safe.

TM: How do you know if a role is right for you?

JM: I look for what responsibility the character has in telling the story. If you remove the role from the story, can you still tell the story properly? And if the answer is no, then I’m interested. From there, I look to see what the human characteristic of it is. What is the thing that everybody from every culture can connect to? And so in The Last Black Man in San Francisco, it’s the idea of home and what that means. Moving on to Da 5 Bloods, it’s that hunt that all children have for their parents’ approval—to be more specific, what is it for a young man to want to connect to his father? More specifically, what is it for a young Black man to want to connect to his Black father? In exploring that, [my character] David is a champion for the young Black man experience. In Lovecraft Country [Atticus Freeman] has so much responsibility because we’re seeing the story through his point of view. He’s our hero, so we’re watching him explore Black masculinity, paternal and fraternal bonds, and the Black family. All these tribes, all these families run through one man. What you see is the prodigal son becoming the patriarch and the burden of that. And that’s quite interesting.

TM: With Lovecraft Country, were you thinking about the additional layer that race brings to the horror genre?

JM: There’s an anecdote that’s really been sticking with me: To be a Black man in America, you are born into the horror genre. You are not safe. Period. Full stop. And when you move out into the world and build for yourself, you realize—and this is Atticus’s story and therefore our story—you are putting yourself in more danger. Atticus is a veteran of the Korean War, and to be in war is a horror story. To be a Black soldier in Korea, it’s a horror story. To then come back to Florida and to live in the Jim Crow South is a horror story. To then get in a car and travel back to Chicago, that’s a horror story. . . . Which is one of the things that made playing Atticus so interesting, because he’s so full. He has so many stories inside of him.

TM: How have you been coping with the two crises Black people are facing: not only COVID-19 but also systemic racism?

JM: I sent a very long text to brother Spike Lee when I saw the news about the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery—the brother jogging in Georgia who was run down and shot by the ex-cop and his kid? That spun me. It happened right around breakfast, and I went to pray over my food, and I just couldn’t shut it off. Even now, the heartache comes in. And I texted Spike, and I said, “Man, f—ed up, ain’t it?” And he responded, “We’re built for this.”

It’s more important than ever to continue. Right now we want to get angry. We’re going to get really angry, but don’t lose your mind. You have to allow the rage and the heartache to make you smarter. And then stay in your lane. Whatever it is you do, double down. I’m an actor. I’m an artist. I’m doubling down on that. And I pray that everyone else does that too. Take the heartache and take that rage, and double down on your anointing. Make better what you have, and you have best.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Acting Majors.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Television

- Jonathan Majors