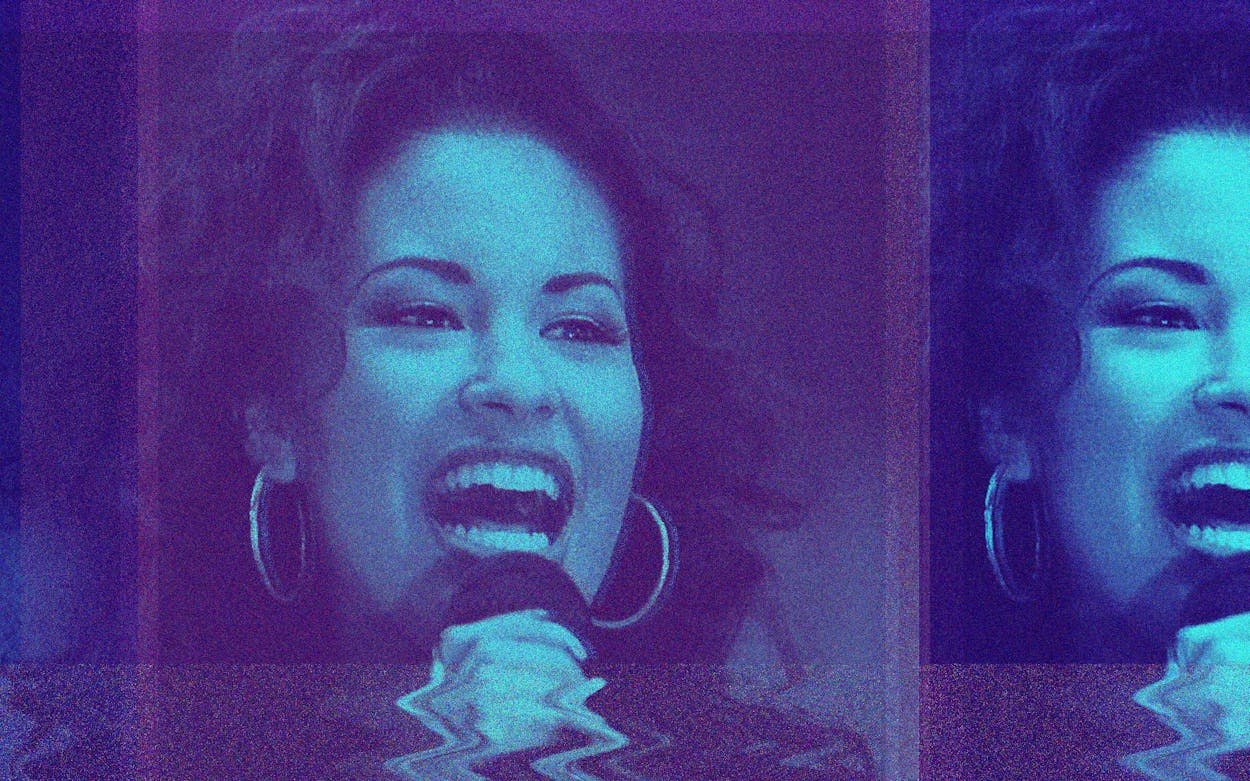

When Selena died in March 1995, fans were desperate for a piece of her. Within a few hours of the news, record stores on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border were selling out of her albums. By the following week, sales of Amor Prohibido had shot up; a week later, they increased again by 580 percent.

When Selena was shot, she was on the verge of releasing her fifth studio album, Dreaming of You—the bilingual crossover record that she had been working toward her entire career. Upon its release that July, it became the first posthumous album by a solo artist to debut at number one on the Billboard 200 chart.

In the 27 years since her death, there have been 23 new Selena albums—soundtracks, compilations, live albums, remixes, and commemorative box sets. And while several of these have charted and even outsold the albums of living artists, in the past few years, Selena’s audience has grown more skeptical of both these releases and the general commodification of her legacy. So this March, when Selena’s father, Abraham Quintanilla, announced that two new Selena albums were on the way this year, the reaction online was mixed at best.

Quintanilla told Latin Groove News that the first record, set for release in April with Warner Music, would include thirteen tracks—three previously released songs reimagined in new styles and ten songs from Selena’s catalog. According to Abraham, his son, A.B., rearranged and remixed music for these ten catalog songs, including one that his sister originally recorded when she was thirteen. “My son worked on Selena’s voice with the computers, and if you listen to it, you know, she sounds on these recordings like she did right before she passed away,” he said in the interview.

Though Selena’s voice is altered in the forthcoming album, it’s not a stitched-together deepfake. As A.B. explained in a December 2021 interview with Tino Cochino Radio, he used thirteen-year-old Selena’s vocals and “detune[d]” them to make her voice sound deeper and more mature, like a digitally created version of the woman Selena was when she died.

The issue of posthumous releases has always been complex. While fans might crave more music from their favorite artists, not all of them want it at the cost of disrespecting or altering a legacy. Mac Miller, Prince, Tupac, and Amy Winehouse are just a few of the artists whose posthumous releases have sparked ethical debates. Does a release honor the musician’s last wishes? Is it an attempt to cash in on tragedy? Does it feel true to the artist? Tupac’s first posthumous album, The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, was already finished when he was killed, and it played an important role in preserving his artistic evolution by being released under his new stage name, Makaveli. But his 2004 album, Loyal to the Game, was produced by Eminem, who manipulated the rapper’s voice to say “G-Unit in the motherf—in’ house.” G-unit wasn’t founded until three years after Tupac’s death.

It’s a subject so touchy that in 2015, David Joseph, the head of Amy Winehouse’s former label, told Billboard he had destroyed the demos from the recording of the singer’s third album to prevent anyone from releasing them. “It was a moral thing,” he said. “Taking a stem or a vocal is not something that would ever happen on my watch. It now can’t happen on anyone else’s.” Joseph took these drastic measures after the release of Lioness: Hidden Treasures, a compilation of unfinished recordings compiled with the approval of Winehouse’s father and the primary caretaker of her estate, Mitch Winehouse. It received a mixed reception from fans, who have been extremely critical of Mitch since his daughter’s death—a relationship that only got worse when he announced his intentions to put on an Amy Winehouse hologram tour in 2019.

Similarly, Selena’s fans have long had a difficult relationship with her father. (Abraham Quintanilla did not respond to multiple Texas Monthly interview requests via his company, Q Productions.) Some accuse Abraham of trying to profit from his daughter’s death. Those already distrustful of his motives saw the album announcement as another cash grab. The news that Selena’s voice would be digitally altered only added to their concerns. L.A. Times writer Fidel Martinez referred to the release as a “robot album,” and though the characterization is a stretch, even I have downgraded from excitement to exhaustion with each announcement of new Selena content.

Since his daughter’s death, Abraham has made it clear that his family has a duty to protect Selena’s image and preserve her legacy. To achieve that goal, Q Productions has sent cease-and-desist letters to several Selena impersonators and even sued Selena’s widower, Chris Perez, who was set to create a series based on his memoir, To Selena, With Love.

I understand Abraham’s intent. But when fans have spent decades watching him shut people who knew and loved Selena out from participating in her remembrance, it seems as though he’s grown most concerned with protecting a singular vision of his daughter: his.

Many of Abraham’s controversial decisions seem to have been informed by the toxic environment created by Selena’s death. As he explains in his 2021 book, A Father’s Dream, “Selena’s image will not be smeared by the lies and unfounded accusations made by [Yolanda] Saldivar and any others who wanted nothing more than to profit from her death,” he wrote. “Honoring her memory wasn’t meant to sell her music; it was a need inside of me that the public remembers my daughter for who she was; a wonderful and loving human being. A beautiful, kind-hearted human being.”

From the beginning of Selena’s career, she made it a point to give herself over to her audience. She stayed late to sign every last autograph. When fans would show up to her house to try and catch a glimpse of her, she would sometimes invite them in. Through her music, her style, and her overall insistence at incorporating American and Mexican influences into her persona, she became something bigger than herself. She came to symbolize the hopes and dreams of our community. It’s understandable that fans feel their own ownership over Selena’s legacy.

So maybe it’s time for the Quintanillas to open up. I don’t doubt their love for Selena or the trauma of the years after her death, which her younger fans weren’t alive to witness. I can hear the excitement in A.B.’s voice when he talks about the upcoming album, and I’m still hopeful that it could be a meaningful reimagining of Selena’s songs.

But as the larger reaction to these albums shows, there’s a fundamental disconnect between the family and all us non-Quintanillas who also adore Selena. The family should embrace the fans and work with them, not against them. Both Tom Petty’s and Prince’s estates have worked with fans to put on tributes to their favorite artists. Aaliyah’s fan sites successfully campaigned for her music to be put on streaming services. In an interview with Mic last year, producer Craig King, who worked with the singer on One in a Million, said these fan sites “have been the only lifeline I’ve seen that’s protected, defended, and uplifted her through the last two decades.”

Maybe then the Quintanillas could trust that we love Selena, faults and all, and that we’ll keep listening to her music, even if it’s not something new. We don’t need more Selena; we just need the real her.

- More About:

- Music

- Selena

- Corpus Christi