His name was Lauwe the Magnificent. The jet-black Friesian stallion stood sixteen hands at the shoulders, about a half foot taller than the petite woman who had just climbed onto his back. Height aside, the horse and rider were well paired. His coat shone like obsidian, and his mane was so robust it had to be wrangled to the side.

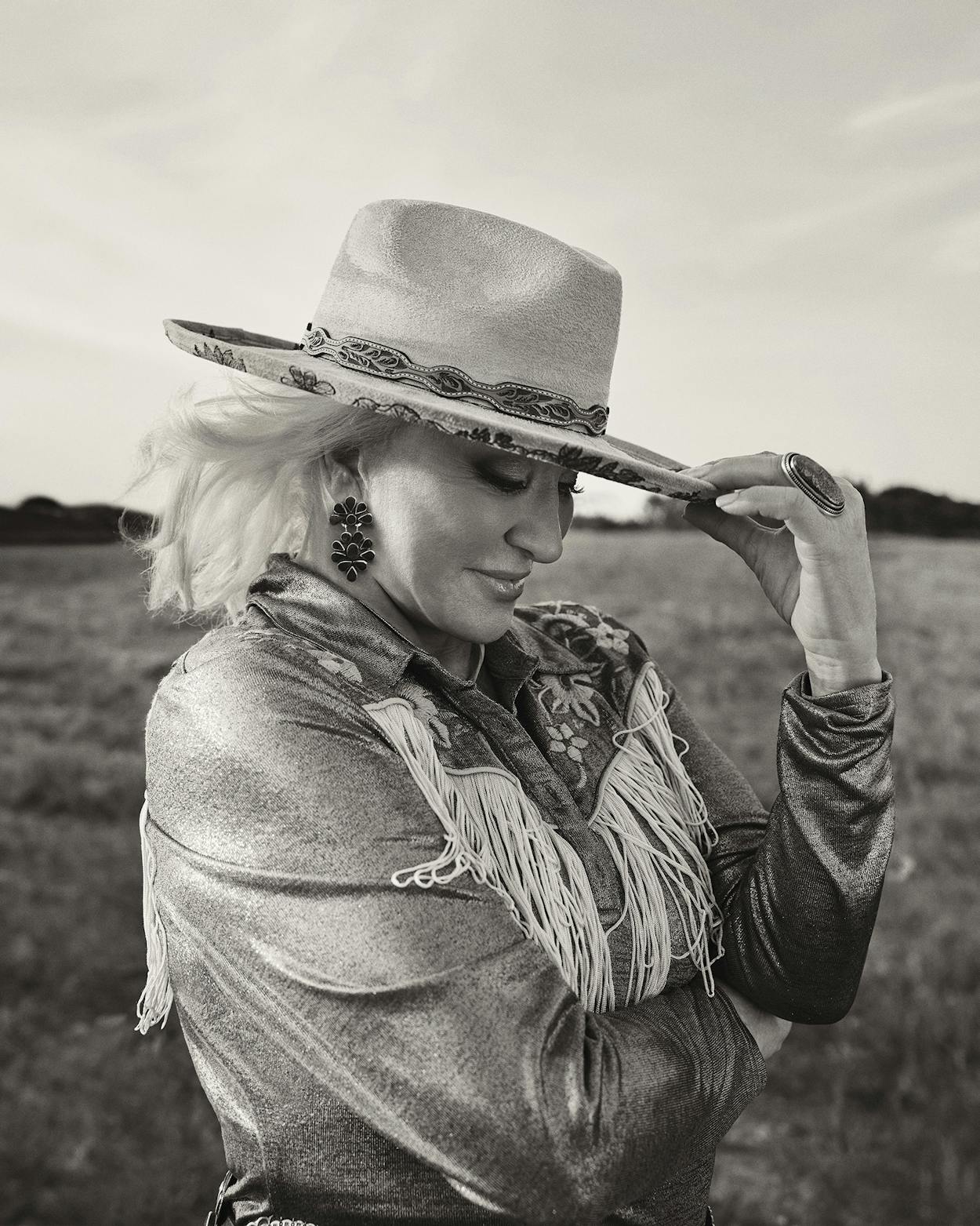

Sitting tall in the saddle was 64-year-old country music legend Tanya Tucker, glowing in a cabernet satin shirt with mother-of-pearl buttons, silver fringe, and enough rhinestone sparkle to cause a plane crash. Her brilliant blond hair and even brighter blue contact lenses reflected the star power she’s exhibited since the age of thirteen. The eyes of every stagehand, production assistant, and publicist were glued to the duo on this recent June evening, but not just because they were starstruck. They were nervous. It would be the first time in history that someone rode a horse onto the stage of the Grand Ole Opry.

Lauwe (rhymes with “how”) was a new visitor to the Nashville cultural institution, but Tucker was a veteran. She first stopped by in 1967, as an audience member, a wide-eyed eight-year-old with lofty dreams and phenomenal confidence. She was onstage five years later, after her debut single, “Delta Dawn,” rocketed her to superstardom. She’s since lost count of her Opry performances.

Usually, Tucker waits in one of the venue’s many dressing rooms before heading to the stage. But Lauwe was simply too magnificent to fit through the backstage hallway, so Tucker and her steed clopped their way through the loading dock and up to a door at stage right. They were flanked by Tucker’s management team, as well as Lauwe’s owners, who were on-site to keep the currently gentle giant from spooking in such an unfamiliar environment. The conversation in the room was muted; no one wanted to admit there might be a good reason that a horse had never been brought onstage at the Opry before.

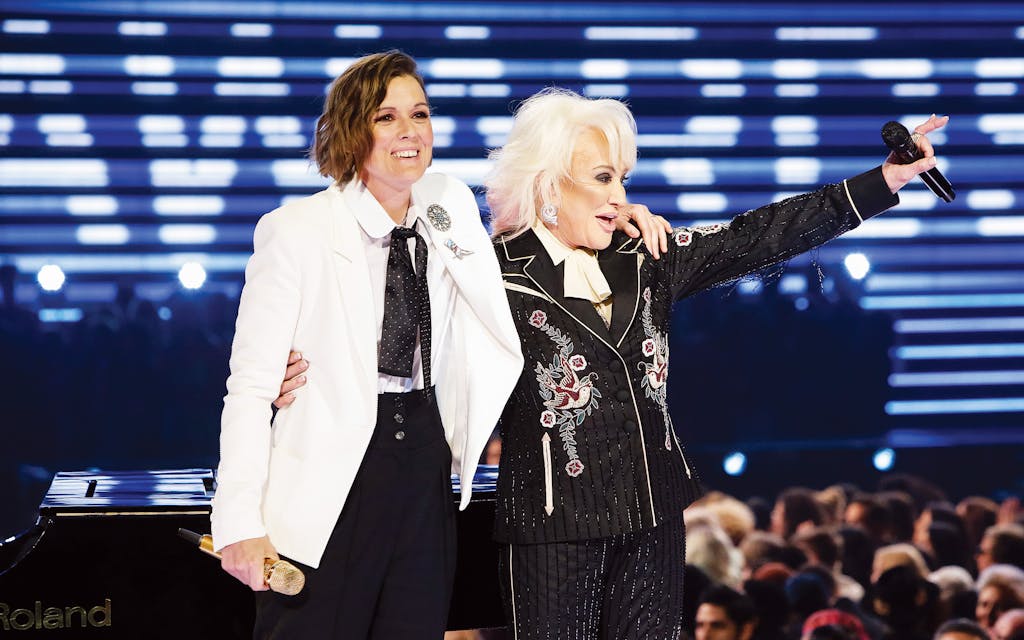

The spectacle had been Tucker’s idea. Earlier in the day she’d released her twenty-sixth studio album, Sweet Western Sound, her second collaboration with the singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile and the producer Shooter Jennings (son of Waylon). It’s the follow-up to Tucker’s Grammy Award–winning 2019 comeback album, While I’m Livin’, which she also made with Carlile and Jennings. To mark the occasion Tucker wanted to go big, and Lauwe is nothing if not that. She had ridden him in Nashville once before, back in April, when they trotted down Lower Broadway on the day the Country Music Association announced that after more than five decades in the business, forty top-ten country hits, and ten number ones, Tanya Tucker would finally be inducted into its Hall of Fame.

The honor was both a long time coming and something that it seemed might never be hers. After all, Tucker had been pissing off the Nashville establishment for at least 49 years of her 51-year career. When she was a teenager she already sounded like an adult, singing about broken dreams, adultery, murder, alcoholism, and sex well before she was old enough to really understand any of those things. Though the public loved her precocious attitude, most of the record executives and disc jockeys who ran Music Row eventually soured on it. By the time she was in her twenties, Tucker was the rare female artist who squarely matched the outlaw-country blueprint. But where Willie and Waylon were lauded for their misbehavior, Tucker was accused of being a floozy, a drunk, and a traitor to her genre. Record executives and concert promoters deemed her past her prime before she turned twenty years old. There were attempts to ban her records as early as 1974.

The Hall of Fame induction was a sign that the Nashville establishment had finally surrendered and admitted that yes, Tucker has been a legend all along. Still, after a career of following her own instincts in the face of industry disapproval, it’s unclear whether she needs the recognition. Or cares about it. In the end, Tucker might choose to welcome Nashville’s belated embrace—or crush it beneath Lauwe’s sturdy hooves. Even in her mid-sixties she has some outlaw moves in her, if that’s the way she wants to go.

As it turned out, there may have been a good reason that more horses haven’t made an Opry debut. When Tucker rode onstage, Lauwe seemed nervous and jittery, picking up his hooves and shaking his head as his trainers held tightly to his bridle and did their best to soothe him. Tucker, by contrast, was the picture of self-confidence. “Good to see y’all,” she told the audience. “This is Lauwe.” Sitting squarely in the saddle, she hit every note of “Kindness,” the new album’s first single.

The audience wasn’t quite sure what to do with the whole scene, but once Tucker dismounted they began to catch on. They hooted and hollered as she wiggled around by the stage’s edge, shaking her hips and stomping her feet in a way that was more silly than sexy. And as soon as the crowd of four thousand heard Tucker growl that first “Delta Daaaaawn,” they started singing along, nearly matching her ardor with every line.

After the Opry performance, more than a month passed before I was able to get some sit-down time with Tucker. A whirling dervish of a woman, she’s famously tricky to pin down. But once she invited me onto her tour bus, our allotted ninety minutes turned into a four-hour conversation about everything from her favorite microphone to her dentist to the anguish of losing a loved one—be it a parent, a beloved pet, or Billy Joe Shaver. The bus, which was built for George Strait, has close to two million miles on it. When Tucker’s not touring she parks it on her ranch so her partner, Craig Dillingham, an accomplished country musician in his own right, can fix what needs fixing before they head back out on the road.

The ranch, located in Briggs, an unincorporated community of about one hundred people roughly fifty miles northwest of Austin, has been in Dillingham’s family since the nineteenth century. Tucker moved down from Nashville during the pandemic, having rekindled her and Dillingham’s on-again, off-again romance, which stretches back to the eighties. (They reconnected, in 2018, thanks to the intervention of their mutual friend Lee Ann Womack, even though the last time they’d seen each other, he says, “Tanya was trying to rip the side mirror off my Yukon!”) They live in a stone house originally built by his parents, a surprisingly modest abode for a woman who has been rich and famous for half a century. It has three bedrooms, two baths, and an extra fridge on the screened porch for storing cold drinks. Above the fireplace sits a portrait of the two of them on horseback, with Dillingham painted as a knight in shining armor and Tucker as the fair maiden he’s just rescued.

“Anyway, I don’t remember what I was talking about,” Tucker said an hour or so into our conversation, before deciding that we’d been talking about the singer-songwriter David Allan Coe. I honestly wasn’t sure. As a lifelong country music fan, I was just delighted to be floating down Tanya Tucker’s stream of consciousness. One second we were discussing a jingle she’d written for the tequila company Cosa Salvaje, which she is a partner in. Then she was complaining about her manager hiring Cindy Crawford’s makeup artist. “My dog could do Cindy Crawford’s makeup! I need somebody that does Joan Rivers.”

Our conversation broke whenever Tucker mentioned a song in her vault then walked over to the Bluetooth speaker her friend Hank had bought her. She would spend a few minutes trying to remember how to connect her phone and find the file in her Dropbox, and then the wood-paneled tour bus would fill with her voice’s trademark sonorous rasp. Tucker rattled off names faster than I could write them down. They were her heroes, friends, and collaborators—people like Carlile, Kris Kristofferson, and Dennis Quaid. She was texting with Shania Twain while I was there (it was very hard not to scream when I learned this). But Tucker seemed far more starstruck by names most people would have to look up: Charlie McCoy, “Pig” Robbins, Billy Sanford, Kent Wells, and other undersung studio musicians and band leaders she has revered since she was a girl.

“If you ask her, she doesn’t have a single enemy,” Carlile says of Tucker. “She is full of love.” The two grew close four years ago while working on While I’m Livin’. Carlile coproduced the album with Jennings and cowrote the Grammy-winning lead single, “Bring My Flowers Now,” with Tucker and two other writers. Harnessing the irreverent witticisms that spew forth from Tucker’s mouth and turning them into a song with verses and choruses and a sense of purpose was a formidable task. “She’s a tough woman,” says Carlile. “There’s a lot of proving that needs to be done before you can gain the trust of an artist like that.”

It wasn’t easy for Jennings and Carlile to get Tucker back into the studio. By the time they approached her, she hadn’t released an album of original songs since 2002, and her career had been off-kilter since her father’s death, in 2006. Boe Tucker spent years as his daughter’s manager and had been her biggest advocate since she’d started performing professionally, in the late sixties. Her career was already in rough shape by the time he died. She was feuding with record companies and was starring in a TLC reality show, Tuckerville. It didn’t get better after he was gone. There were stalled albums, lawsuits, real estate drama, a chemical peel that left her with second- and third-degree burns, and a devastating bout of depression. “At one point, I didn’t get out of bed for, I think, three months,” she once told the television host Larry King. “I went to the bottom of the hill one day, and I had to call somebody . . . to come pick me up because I couldn’t physically walk up the hill.”

Sitting in the tour bus, Tucker said adjusting to life without her father “has been the worst thing of all.” She started singing a slightly altered line from “Waltz Across a Moment,” a song off Sweet Western Sound: “I could still hear him when the night wind comes / Daddy, which way do I go?” She rarely had to second-guess herself when he was around. Boe Tucker was her protector. At the height of her success, he’d been in charge of the money. If she wanted a house, he bought it for her and made sure it was a good deal. He let her focus on being a creative force. “It wasn’t Daddy’s fault that I never looked at the numbers,” Tucker told me. “But it backfired, because now I don’t know how to get a f—ing insurance policy.”

When Jennings and Carlile approached her in 2018 about recording an album, Tucker had been trudging along for more than a decade. It wasn’t like she’d disappeared. She was touring, but most of her shows were at casinos and county fairs, and she hadn’t been able to persuade a label to release an album she’d self-recorded. (“The album’s called Messes, because I like that title—‘Tanya Tucker: Messes,’ ” she told me, sweeping her hand in front of her as if to visualize it on a marquee.) Her career had invited so much scrutiny in her early years that she wasn’t sure she wanted to put herself back in the spotlight. She also wasn’t sure she wanted to record an album of gentle Americana, which is what Carlile and Jennings were pushing on her—Tucker was best known for a harder-edged sort of country music. And she wasn’t sure, either, that she wanted to record an album of songs that had been picked by Jennings and by Carlile, whom Tucker had never heard of.

But Carlile was persistent. “We kept sending Tanya songs and she kept trying to back out of it—whether it was insecurity or just not understanding what was possible for her. Getting her to do the record was a really long grassroots process.” When While I’m Livin’ was done, Tucker had not only an album of new material but also a trusted advocate in Carlile. And not just any advocate—Carlile was an avatar of a new, more inclusive country scene than the one Tucker had come up in, and she had multiple Grammy awards, a certified gold record, and a lot of goodwill in Nashville.

Tucker would need the help. When Carlile started shopping the album around, she was surprised by the pushback. “I was getting reactions like, ‘Oh, no, no, no, no. We don’t even want to hear about it. Tanya this and Tanya that,’ ” she recalls. “And I’m thinking, ‘But nobody’s heard from Tanya in twenty years. What are you talking about?’ There was this unforgiveness and rigidity. The male outlaws that did the same drugs and had the same lifestyle and said these same words are revered beyond belief. We sing their songs in church. In church. To get Tanya a second chance was like a miracle. There was no reason for that. She should have never been outside.”

The tale of the obedient child and the overbearing stage parent is a familiar one, but there are two things to keep in mind when looking at Tanya Tucker’s early career. One, the profoundly stubborn Tanya Tucker rarely does anything she doesn’t want to do, and two, Boe Tucker raised his daughter to believe she could do anything. Hell, he taught her how to drive a stick shift when she was four. Later, when his daughter, then nine years old, told him she could be a country music star, he did something else not many parents would: he took her seriously.

“He quit a job!” Tucker recalls of her dad’s commitment to supporting her dream. “He was the first one that believed in me. Without him, nothing would have ever happened.”

The former well digger, cotton picker, and roughneck had grown up extremely poor in Depression-era Oklahoma. As an adult he moved his family of five from the southern Panhandle town of Seminole—where Tanya, his youngest, was born in 1958—to Arizona, Utah, and Nevada in search of honest work. He was always hustling, and beginning in the late sixties he applied that hustle to getting his daughter on as many stages as he could.

When they were living in Wilcox, Arizona, the Tuckers frequented the local Veterans of Foreign Wars hall, where Tanya sang one of Hank Williams’s most famous songs so often that everyone called her “Little Miss Cheatin’ Heart.” Boe Tucker would drive the whole family to wherever their favorite artists were playing, then go around back, find the tour bus, knock on the door, and tell Tanya to sing. That’s how she ended up performing with the likes of Ernest Tubb and Mel Tillis before she’d turned ten.

Billy Sherrill, a Grammy-winning songwriter and producer, had made Tammy Wynette a superstar and revived George Jones’s career, but he still let a thirteen-year-old girl boss him around a little. Nearly every Tanya fan is familiar with the story of how she found “Delta Dawn.” It was 1972, and she had just signed with Sherrill and Columbia Records. Tucker was in Sherrill’s office, along with several suits from the record company, trying to settle on something that could work as her debut single.

One of the men started playing a copy of a newly written song called “The Happiest Girl in the Whole U.S.A.,” a joyful tune sung from the perspective of a young woman newly in love. When it was over, Sherrill asked Tucker what she thought, and the teenager told a room full of adult men, who held her family’s financial security in the palms of their hands, that it was a real nice song, and that it’d make a real nice record—for somebody else.

“Delta Dawn” was different. Sherrill had heard Bette Midler cover the song on The Tonight Show the night before, and he played Tanya the original version, by the Tennessee songwriter Alex Harvey. Tucker had little to no understanding of the song’s subject, but as soon as she heard the line “She’s forty-one and her daddy still calls her ‘baby,’ ” she was sure the song was hers.

She still can’t quite explain where this certainty came from. Sometimes she chalks it up to youthful naiveté. “You know how you’re a kid and you just spit it out? I’ve always been that way. The younger I was, the more truthful I was.”

“Delta Dawn” came out in April 1972 and immediately bore out Tucker’s and her father’s confidence. It went to number six on the Billboard country charts, and Tucker, once barely known beyond the patrons of the VFW in Wilcox, Arizona, was a worldwide star.

By the time she released her first album, in September of that year, the Academy of Country Music had crowned her Most Promising Female Vocalist. The following year Tucker had back-to-back number one hits with “What’s Your Mama’s Name, Child” and “Blood Red and Goin’ Down,” two songs that, perhaps obliquely, seemed to acknowledge that the person singing them was a child. Of course, since that child was Tanya Tucker, one of the songs is about a man who spends his life trying to track down his daughter and dies without ever learning her true identity, and the other is about a little girl who watches her daddy murder her cheatin’ mother under a honky-tonk’s neon lights. With her gruff alto and her ability to convincingly put across lyrics whose meaning she couldn’t fully comprehend, Tucker proved herself a master of the sort of depressing story ballad—think Marty Robbins’s “El Paso” or Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe”—that had been a country music staple since the genre’s inception.

Predictably, at around the time Tucker started looking more like a woman and less like a girl, there was backlash. Shortly after her fifteenth birthday she released “Would You Lay With Me (In a Field of Stone),” a song that David Allan Coe had originally written for his brother’s wedding vows. She still insists the song is a beautiful tribute to love and commitment, but when it came out, at the end of 1973, not many people agreed. Radio stations refused to play it, preachers railed against it, and promoters forbade Tucker to sing it at their venues. The song’s notoriety, as it happened, helped make it her third number one single. It didn’t matter. Tucker was tainted.

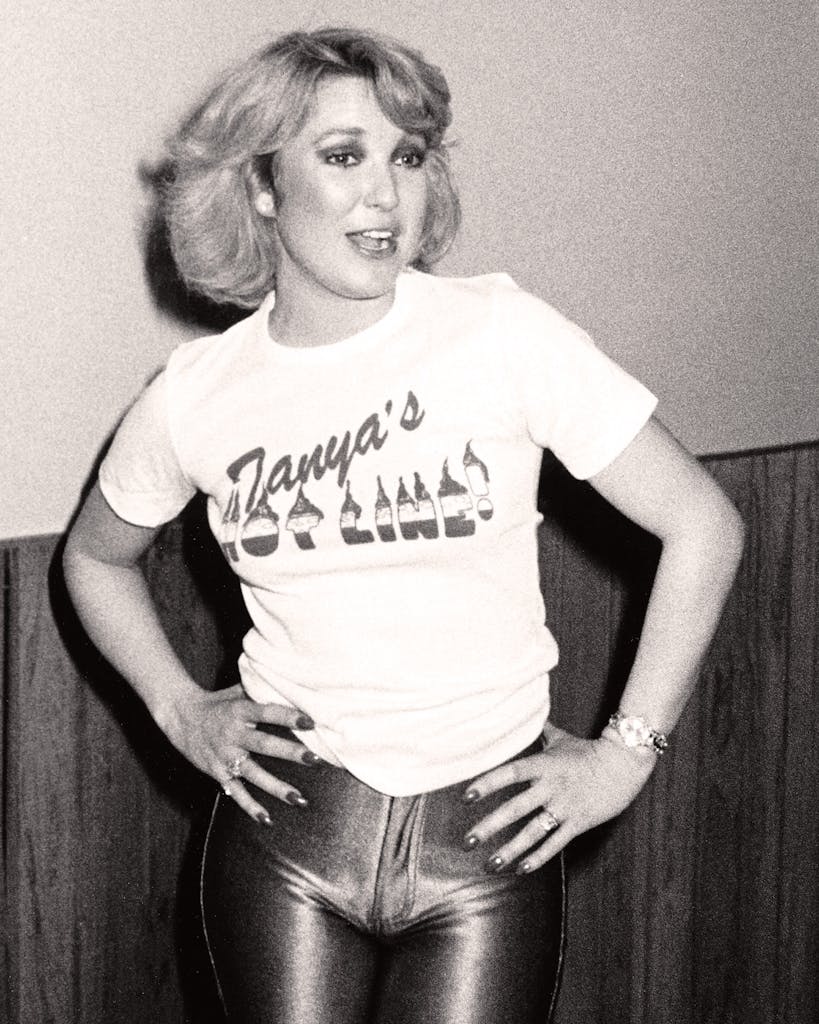

“Once she was an object of lust, nobody talked about her music,” wrote Holly Gleason in “Tanya Tucker: Punk Country and Sex Wide Open,” an essay included in a 2017 book about female country musicians. One need only look to the September 1974 Rolling Stone story “Tanya Tucker: Teenage Teaser” to see Gleason’s point. “Her face was a study in wide-eyed childish innocence, but her body had another message, and her knee drops and pelvic thrusts raised the temperature several degrees around the stage,” wrote music journalist Chet Flippo. The story introduces Tucker via the eyes of a 39-year-old man in the audience, Red, who is wearing a sweat-drenched T-shirt that doesn’t even cover his beer belly and is “breathing heavily and swaying in time” while “staring straight into the most beautiful navel in show business.”

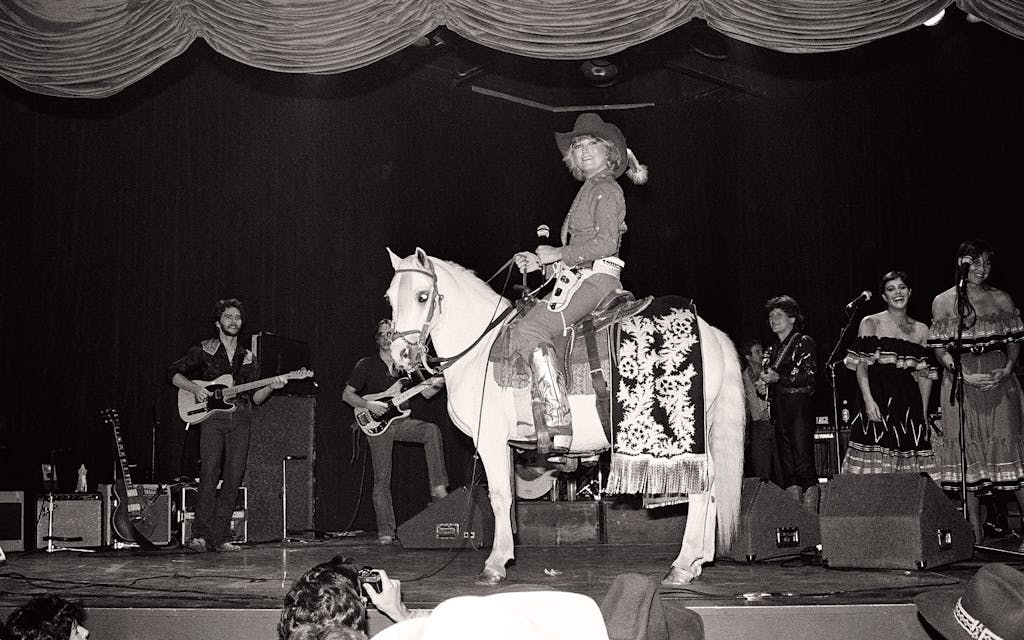

Tucker’s midriff may have tormented Red, but she had no reservations about leaning into her newfound sexuality and rebelliousness. “She was a wild-ass bitch with a chain saw in her throat,” says Gleason now. “She was fearless to the point of almost being reckless. But she never lost control, so you couldn’t take your eyes off her.” In 1978 Tucker released her first “rock” album, TNT. Critics on the coasts praised it, but country fans accused Tucker of leaving Nashville in the lurch.

“Oh, I’m a badass, a bad girl,” Tucker told me, mocking the narrative that began to take shape during this time. Her run of hits slowed down in the early eighties, and the world got real upset when she started dating Glen Campbell, a man 22 years her senior with a world-class cocaine habit. “There was no doubt that he loved me, and I loved him,” says Tucker, who still looks back fondly on the relationship. “I just wish I had been a little more mature.”

Tucker moved to Los Angeles and her career stalled; she released three albums in the first half of the eighties, but only one single, “Can I See You Tonight,” cracked the top five. Boe Tucker tried to steady his daughter. He once persuaded her to fly to Nashville to visit her mother, and while she was in the air, he was out in California moving her out of the party house she was living in. She was as famous as ever, but mostly because her romantic exploits, substance abuse, and near-constant partying were tabloid fodder. As with LeAnn Rimes, Britney Spears, Taylor Swift, and countless other young starlets who had the audacity to be unkempt, sexual, chaotic, or otherwise less than pristine, many journalists were just waiting for her to crash and burn.

Tucker isn’t resentful. “Those rags, as shitty as they might be, they kept me out there,” she told me. “I wasn’t making records for several years in the eighties, but I was on the cover of the [National] Enquirer about every other week.” That bad reputation, though, didn’t help her in the industry. When she wanted back in the studio, it was hard to persuade the boys’ club to give her another chance. (This time around, even Sherrill passed.) But she still had name recognition (thank you, National Enquirer!), and when Girls Like Me came out, in 1986, it blew up, kicking off a decade-long string of successes for Tucker, then 27.

She earned 23 top-ten country singles and four number ones during this time, but, more important, she had a point to make. On TNT, Tucker had tried to bring Nashville out of the “horse-and-buggy era”—to infuse it with the grit of the rock world and the grandiosity of pop music—to mixed results, by her own account. A decade later she finally found a way to make it happen; songs like “Down to My Last Tear Drop,” “Girls Like Me,” and “Highway Robbery,” bolstered by guitar licks, synthesizers, and an even more raucous Tucker, showed that she had finally lived up to a nickname that had been following her around since the mid-1970s: “female Elvis.”

Though the Nashville establishment would embrace other artists who later mated country, rock, and pop, such as Garth Brooks and Shania Twain, it wasn’t impressed with Tucker. In the Country Music Foundation’s 1998 Encyclopedia of Country Music, the Tanya Tucker entry devotes only one of eight paragraphs to this era of her career, and it doesn’t say much about the music. “The tabloid press began to take a full-time interest in Tucker again. She gave them plenty to work with,” it reads, before mentioning that she checked into the Betty Ford Center to deal with her substance abuse issues and that she gave birth to her daughter, Presley, out of wedlock (egad!). The passage about her being named the Country Music Association’s Female Vocalist of the Year in 1991 merely notes that she found out about the honor on the night she gave birth to her second child, Beau Grayson, while “still unmarried.” There’s no discussion of What Do I Do With Me, the album that earned her that award, or the three studio albums that followed. There is a reference, though, to 1997’s Complicated, a commercial flop that so soured relations between Tucker and Capitol Records that she asked to be released from her contract.

She had her third child, Layla, in 1999 (and no, she wasn’t married then either). In 2002 she released Tanya on her own label, Tuckertime, a subsidiary of Capitol Nashville, and it sold even fewer copies than Complicated. By the mid-aughts the Nashville establishment was ready to write her off again. Then her dad died, then her mom died, and it was hard enough for Tucker to get out of bed, much less orchestrate another comeback. She released an album of covers, My Turn, in 2009, and a couple of live records. She toured year-round, playing casinos and county fairs. Fans always wanted to hear Tanya Tucker sing the hits, and she had more hits than she could fit into a single show. There was “Delta Dawn,” “Two Sparrows in a Hurricane,” “Here’s Some Love,” “Texas (When I Die),” and one that seems like a summary of Tucker’s whole life: “Some Kind of Trouble.”

I’ve been in this business forever but I don’t know a damn person,” Tucker told me, trying to explain why it took so long for the Country Music Association to induct her into the Hall of Fame. “I don’t know any managers, I don’t know any producers. I know a few. And musicians? I mean, I know the old guys, but I don’t know a lot of the new ones. I just feel like the longer I’m in this business, the less I know about it.” She’s never had much use for the politicking side of showbiz. “That’s why everybody says I’m not in there already.”

Gleason agrees. “Tanya has come in and out of Nashville for quite some time, and she’s not worried about what’s happening on Music Row—she’s worried about where she’s going to find the next great song. Everybody just finally looked around and thought, ‘Holy shit, Tanya’s not in the Hall of Fame.’ ”

Not that the official imprimatur means all that much. “Tanya’s a once-in-a-century artist,” says Carlile, with no hint that she’s engaging in hyperbole. She’s talking about Tucker’s singing and stage presence, of course, but she’s also talking about what Tucker means to her listeners, more than a few of whom became her peers. Her rebelliousness made her a queer icon decades before Maren Morris and Kacey Musgraves began showing up at the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) awards. She’s beloved by a slew of female country artists—such as Miranda Lambert, Shania Twain, and Gretchen Wilson—who are proud graduates of the Tanya Tucker School of Not Giving a F—.

“She sounded like a brawler,” Carlile explains. As a queer kid growing up in rural Washington State, Carlile loved country music but was drawn to Tucker in particular. “Tanya’s voice was standing out from all the others. She was tough, and there was something about that that suited how I understood myself in that time.”

Carlile isn’t alone. “I grew up as a queer kid in the Deep South, and you would grab on to any kind of misfit or rule breaker that you could find,” says Kathlyn Horan, the director of the 2022 documentary The Return of Tanya Tucker: Featuring Brandi Carlile. “Because of who she is and how she lived her life—being a hundred percent herself and unapologetic—Tanya represented that to the gay community.”

“She’s butcher than me, and she’s straight as an arrow!” Carlile says, adding that she doesn’t think Tucker is all that intentional about supporting the LGBTQ community. “She isn’t even a passionate advocate. It’s just it would never occur to her to not accept someone for who they believe they are.” Tucker was a guest on RuPaul’s Drag Race in 2010, years before it was a mainstream hit that celebrities were eager to associate themselves with. “They asked me to come on the show, and I just did it. I didn’t have any preconceived notions about it,” Tucker says of her decision to be on the program. RuPaul, as it turned out, was a big admirer of hers. “He named some songs that were so deep in the album that you’d have to be a fan to know, and then he started tearing up,” Tucker says. “I knew he was genuine.” She has since appeared on Drag Race a second time, and in 2021 she released a country-rap duet with RuPaul, “This Is Our Country.”

“Our favorite LGBTQ+ icons are a dichotomy of varying qualities—strength, will power, and resilience coupled with vulnerability, creativity, talent and humanity,” RuPaul says. “Tanya Tucker is all of those things.” (He also notes that “I own every record she’s ever put out, and I love them all.”)

The Nashville establishment has always been a conservative, overbearing force; for decades many country stations have largely refused to play songs by female artists back-to-back, and in 2015 a prominent radio consultant said, “If you want to make ratings in country radio, take females out.” During the seventies, eighties, and nineties, it seemed like female artists were making some headway; by the end of the twentieth century, acts such as the Dixie Chicks, Faith Hill, and Shania Twain represented a third of country radio airplay. But that popularity began to wane in 2003, when Natalie Maines, of the Chicks, told a crowd in London that she was embarrassed that George W. Bush was from Texas. As recently as last year, a study showed that women represented just 11 percent of the songs heard on country radio.

It ain’t all bad. Recently a handful of women—many of them Texans—have found massive critical and financial success playing by different rules. Carlile, Morris, and Musgraves have racked up awards and sold out arenas, despite being unapologetically open about their sexuality and liberal politics. (Carlile and Morris are also members of the supergroup the Highwomen, whose 2019 debut album went to number one on the country charts.) Taylor Swift, who, like Tucker, signed with a Nashville label when she was thirteen years old, may have left country music for the pop scene, but she is arguably the most commercially successful female singer-songwriter ever. Miranda Lambert, who named her dog Delta Dawn, has been able to break through on country radio on her own terms, with top-ten singles about drinking, sex, and shooting a man who’s done her wrong. Shania Twain is in the middle of a wildly successful comeback tour, and her career can be traced back to a 1979 appearance on a Canadian television show when, as a fourteen-year-old trying to break into the business, she sang Tucker’s “Texas (When I Die).”

“There’s a grit to it and an audacity to it. It’s like ‘camel toe’ country,” says Carlile, using an off-color slang term to describe Tucker’s belligerently feminine style and influence. “Just look at Miranda Lambert, or Gretchen Wilson, or, oh my god, even Lainey Wilson,” she added, referring to Nashville’s newest celebrated ingenue. “There’s no way they’re not influenced by Tanya, even if they don’t know it, even if they’re influenced by somebody who’s been influenced by Tanya.”

Sitting in her bus, Tucker rubbed her left shoulder, trying to alleviate the nerve pain that had been torturing her for days, ever since she rode up to Wisconsin and back in one day, for just one show—a 24-hour drive each way. The trip was worth it, at least to Dillingham, Tucker’s partner, who said it had been amazing to watch a crowd of thousands—whose “heads looked like a bunch of watermelons in a field”—singing along when Tucker closed with “Delta Dawn,” as she does most shows. As soon as they’d made it back to Austin, they went downtown to the Moody Theater so Tucker could record an episode of Austin City Limits, her first time on the program since 1986. At that performance she had turned her exhaustion into a bit, joking with the audience that whoever sets her schedule must have it in for her.

The day after the ACL taping, when we were due to take photographs for the cover of this magazine, Tucker’s arm hurt so badly that she lay down in the tour bus, in tears, in the dark. “I thought, ‘Oh my god, am I gonna have to weather the old “She’s out there, not doing her shit” story again?’ ” (A few weeks later, after she had surgery to alleviate the pain, she texted me a lyrical, rambling poem about horseback riding into the sunset with Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson, and then wrote, “OH MY GOODNESS what kind of pain meds are they giving me here!!!”)

She’s aware of the double standard her career exemplifies—“If I acted like Hank Williams Jr., I’d be tarred and feathered!”—but she mostly thinks about the work in front of her. Creating music is as joyous for her as it was when she was a teen. It’s the perfect combination of the two things she loves the most—singing with passion, just like Hank Williams used to do, and being around the people she loves and who love her right back. Which may be one reason she never bothered to lobby for a Hall of Fame slot—the people whose approval means the most to her are already at her side. With both of her parents long gone, Tucker surrounds herself with family or with people who feel like family. Her daughter Presley sings backup at every show, her daughter Layla opened both nights that Tucker performed at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium last June, and her son, Beau Grayson, also a musician, was backstage. Most of her touring band has been with her for years, and they know how to work with Tucker, how to pick up and play when she starts breaking into a random old gospel song that just popped into her mind. She has a habit of holding on to those she bonds with, such as Kristy Johnson, who helps organize Tucker’s life in Briggs. They met in 2020, when Tucker hired her from a home health-care service to help her recover from an ankle injury. Johnson is still a big presence in Tucker’s life even though Tucker’s ankle has long since healed enough that she can shake and shimmy with abandon onstage.

At one point, Tucker insisted that I watch the video she had just shot for “When the Rodeo Is Over,” the second single off Sweet Western Sound. The song was chosen by Shooter Jennings, who had no idea that it was cowritten by Dillingham twenty years ago. (Tucker loves this coincidence so much, she talked about it at all five concerts I attended this summer.) Tucker hired longtime friend Joanne Gardner to direct, and they shot at the Y.O. Ranch, forty miles west of Kerrville—one of Tucker’s favorite places in all of Texas—with a cast full of retired rodeo riders that Tucker has known over the decades. “That’s my ex!” she told me proudly, pointing out her second-ever boyfriend, champion saddle rider Bobby “Hooter” Brown. She then spent a long time trying to find the video she shot last year with Kristofferson and Dennis Quaid, going into detail about how she found the song, and how she persuaded Kristofferson to do it, and how she got John Carter Cash (June and Johnny’s boy) to direct.

She played me songs she’d recorded for Messes, including one with the line “It ain’t hard for a girl like me to be one of the boys.” Tucker’s voice had a recognizable fervor—the “chain saw” that Holly Gleason mentioned—something that was in short supply on While I’m Livin’ but is more prominent on Sweet Western Sound. It’s as if the recent recognition from Nashville had given her the leeway to foreground the fearlessness that made her stand out in the first place. Maybe she doesn’t need the approval of the Country Music Hall of Fame, but if the organization is going to offer it up, she’ll make the most of it.

At this moment, though, Tucker was more concerned with how to get Lauwe involved in her Hall of Fame induction, which will take place at the Country Music Hall of Fame’s CMA Theater on October 22. “He can’t go into the building because he’s too big,” she says. “But I want to ride him up to the door. Why not?”

This article originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Outlaw.” Subscribe today.

Photography Credits, Hair: Rod Landers; Makeup: Kati Swegel; Styling: Cristina Facundo; Wardrobe provided by Double D Ranch

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Austin