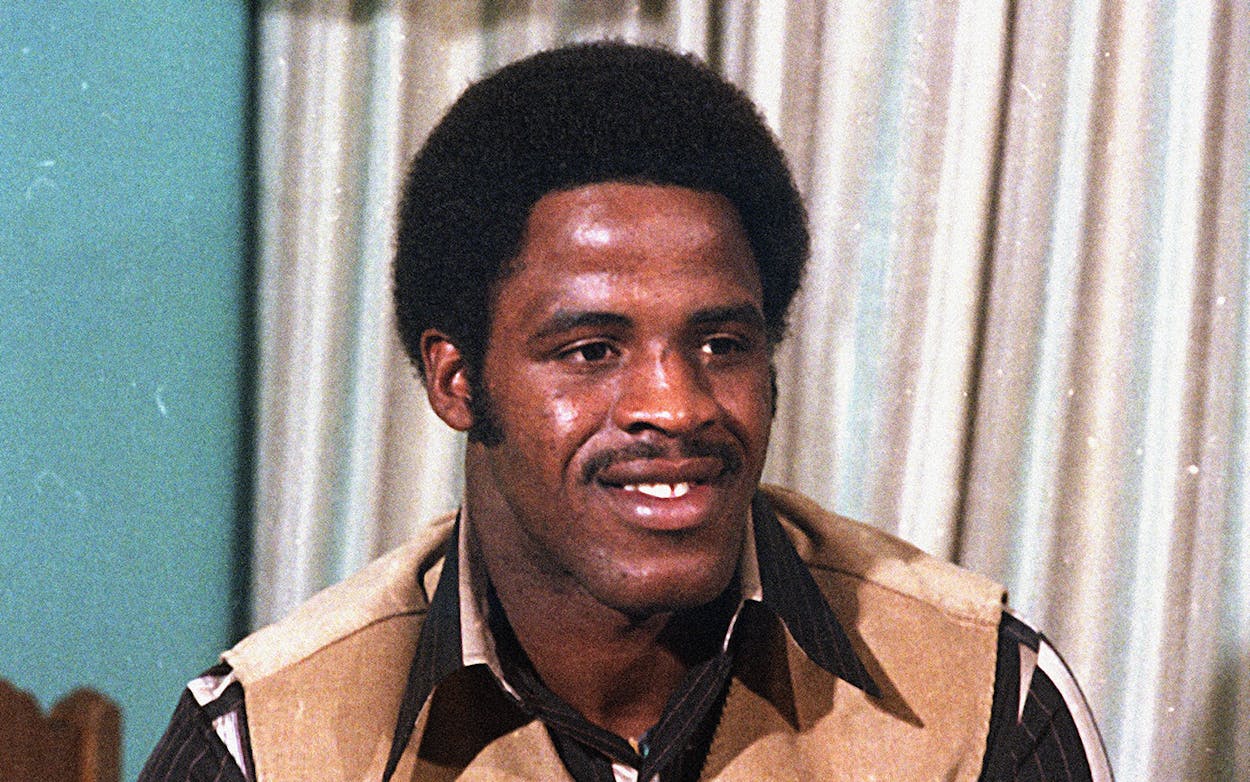

Elmo Wright was exactly the type of recruit Darrell K. Royal needed in 1966. He had only started playing receiver at East Texas’s Sweeny High during his senior year, but he was a natural; he once scored five touchdowns in a game. He had the talent to play anywhere, but he knew what his top choice was. “I’d love to go to the University of Texas,” he told his coach. “I’d like to be the first Afro-American to play there.”

As Asher Price writes in his deeply researched and reported biography, Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact (UT Press), Royal invited Wright to visit Austin and spoke with him in his office. “You’re going to have to be like Jackie Robinson,” the legendary coach told him.

After the meeting, Royal called Wright’s high school coach. “He’s the real deal, grades and everything,” Royal said. “But, unfortunately, at this stage of the game we’re not ready to take that step.” Wright ended up at the University of Houston, where he was named an All-American receiver and, among other things, invented the end zone dance, and then went on to play five seasons in the NFL.

Earl Campbell, as an eleven-year-old living in Tyler when Royal dashed Wright’s dreams, was no stranger to racism either. If Campbell wanted to buy a hamburger at the local diner, he had to get his food to go, served out of the back door. On his way home, he and his brothers often ran, to avoid trouble with white neighbors.

Both the Longhorns football team and the Tyler school system were finally integrated in 1970, sixteen years after Brown v. Board of Education and a few years before Campbell got to join the team from which Wright had been barred. He was, in short, a target of some of the worst prejudice that America had to offer and a witness to the profound changes in race relations that occurred in the middle of the last century. Price, a longtime reporter for the Austin American-Statesman, makes the most of Campbell’s prominence at such a pivotal moment, using Campbell’s experiences to unravel the ugly history of integration in Texas—first in Tyler, then in Austin, and finally in Houston.

Some may regard this focus as counterintuitive. At first glance, it seems like Campbell wasn’t on the forefront of sports’ battle to integrate. By the time Campbell arrived in Austin, black stars were household names in every major sport: Hank Aaron in the MLB, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in the NBA, Jim Brown in the NFL, and Ernie Davis in college football. The hyper-racial sports world of the sixties—when Muhammad Ali, Bill Russell, and Olympic medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos pressed white America’s buttons—had long faded by the time Campbell won the Heisman Trophy in 1977.

Fortunately, Price decided to drill into the issue even so, and discovered material that more than justifies his book’s thesis. Earl Campbell is an argument against the insistent calls for athletes and sportswriters to “stick to sports” and ignore the larger world—an argument we still hear in the age of Colin Kaepernick and the NBA vs. China. Campbell and Royal were among those who tried to keep their focus on what happened on the field. On the night he won the Heisman, the running back told a reporter, “I don’t see Earl Campbell as a black man. I see Earl Campbell as a man. I have too much other stuff going on to be drilling on the black and white issue.”

In Austin, that issue had a lengthy, troubled past. Price has uncovered revelatory documents showing the lengths to which regents and administrators went to prevent full integration of the university. In July 1955, UT became one of the first public universities in the country to require entrance exams. The reason? The regents calculated that they could admit fewer black students if they raised admissions requirements. But as slowly as change happened on campus, the status quo was even more stubborn for the football team, the final UT association to make a place for African Americans. “It was one thing to admit African Americans, another to allow them to play on the football field,” Price writes.

The longer the Longhorns held out on integrating the team, the more Royal’s reputation with black families deteriorated. It was so bad, in fact, that the first time he met the coach, the running back said, “I understand you don’t like black people.” Price takes great care to examine Royal’s culpability. Was he indeed racist, or was he, as he claimed at the time, playing politics with the regents? Price seems to settle somewhere in the middle. Royal didn’t harbor any ill will towards his African American players, Price believes, but he didn’t go out of his way to help them either. Royal’s biggest offense, it seems, was his indifference.

Campbell seemed to take his coach’s lead. When asked about race, he would tell reporters, “You might hear things about white and black people down here, but I don’t see it on this campus.” Price makes it clear that Campbell’s assessment couldn’t have been true: when he arrived on campus in 1974, there were only 600 African American undergraduates, 1.5 percent of the overall student body. Only thirteen of the 1,600 faculty members were black. Before the Texas A&M game in 1977, a large sign was painted on the side of a campus building at the pre-game pep rally asked, “If an Aggie and a n—– jumped off the [UT] Tower at the same time, which one would hit first? Who cares?” A UT press release a few weeks later boasted that Campbell loved the team dining hall’s fried chicken.

Campbell chose instead to let his play talk for itself. The touchdowns, broken tackles, and rushing records spoke loudly. A decade before Campbell arrived on campus, when there was talk of the Longhorns integrating, an angry fan wrote a letter to the chancellor asking, “Can the star negro of a future Texas football team be taken home and accepted over weekends in some of our best homes?” By the time Campbell entered his junior year, his (white) tutor invited him to dinner with his family. Every boy in the neighborhood lined up to get his signature.

Price writes that black students felt unwelcome at sports events before Campbell arrived at UT. Julius Whittier, the first black player to join the Longhorns, told the Associated Press in 1972, “Since when you seen orange…doing us a favor?” But with Campbell on the field, the African-American community embraced the Longhorns. Some black students recounted that the first question they heard when arriving home was, “Have you met Earl?” Others called him “a symbol.”

That symbolism is exactly why sports and politics can’t help but become entangled. Sports, it’s often asserted, is valued for its ability to allow us to leave behind the everyday world of conflict, negotiation, and sometimes grueling compromises. There’s something to that, for sure—there are few greater pleasures than gazing at a football field and forgetting whatever problems you might be having at home or at the office, or getting so wrapped up in the last few minutes of a close basketball game that your field of vision telescopes and time slips away. But sports has never been just a means of escape. Like books, music, film, and television, it’s a venue that allows us to watch the great issues of the day play out, usually at a safe remove.

This past summer, the U.S. was mesmerized by the Women’s World Cup not because we suddenly became a country obsessed with professional soccer, but because the American team’s success tapped into feelings of national pride and pride in our society’s advances in gender equality. We can say the same about Earl Campbell—it’s not just those glorious sprints down the field that we remember him for. Heisman winners come and go; it’s Campbell’s grace under pressure as a black man in a time of racial upheaval that endears him to so many.

“Though Earl Campbell tried, through carrying the football, to transcend race—and open-minded as he was—race, exhaustingly, remained a prism through which Texans, and Americans generally, saw one another,” Price writes. Campbell’s leadership in taking the Longhorns to a national championship showdown against Notre Dame in the Cotton Bowl was the sort of thing that forced at least some white and black Texans to wonder if the world could be a different place than the one they had been raised to believe it was. If a black man could lead the Longhorns, one of the last bastions of white supremacy, what else was possible?

In the book’s most moving passage, Price talks with Ron Wilson, a black classmate of Campbell’s. “When he got the football, he was a monster,” Wilson says. “That’s kind of an activism.” Tearing up as he remembers that time, Wilson continues: “The way he’d run, run over people, man just flatten them…That to me was the ultimate—what’s the right word?—the ultimate sacrifice for his people and for him.”

And what did Wilson do after watching Campbell take control of the Longhorns? In 1977, during Campbell’s senior year, he got himself elected to the Texas legislature, where he served for 27 years.

- More About:

- Sports

- Books

- Texas Longhorns

- Earl Campbell

- Tyler