WHO: Murray Cohen, a commercial pilot and volunteer fossil-hunter with the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, in Dallas, and the rest of the museum’s paleontology team.

WHAT: A newly discovered plant-eating species of small dinosaur, Ampelognathus coheni, that lived in North Texas 96 million years ago.

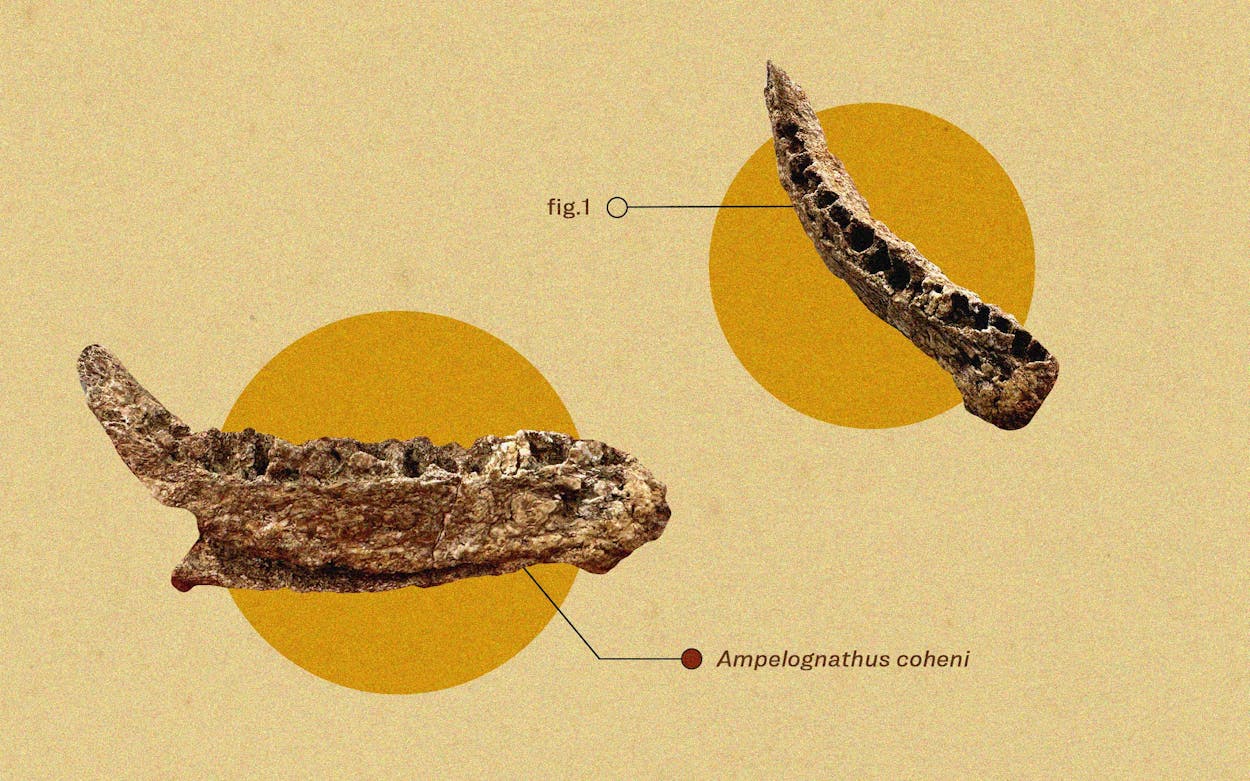

WHY IT’S SO GREAT: In September 2019, Murray Cohen, a pilot who volunteers with Dallas’s Perot Museum, was fossil-hunting on his own when he found a two-inch-long jawbone in a sandy area near Grapevine Lake’s spillway, about thirty miles northwest of downtown Dallas. He later handed the muddy bit of bone over to the Perot’s researchers, who cleaned it carefully under a microscope in a lab with miniature needles to get a better look. They thought at first that the jawbone might have belonged to a crocodile.

Then the scientists spotted an even smaller bone feature that once connected the lower jaw to a beak. That was thrilling, recalls Ron Tykoski, the Perot’s vice president of science and curator of vertebrate paleontology, because it meant the fossil could only be from one kind of creature: a dinosaur.

Tykoski’s team began trying to identify the bone. Texas was once home to about twenty of the more than three hundred dinosaur species known worldwide. A few other, much larger dinosaurs had similar features to the new find and lived in that area, but none seemed to match. Tykoski said that while the team wondered if it could be a new species, they spent four years trying to prove that assumption wrong. “After trying really hard for a long while to make it fit into previously known animals, we were getting frustrated by that,” Tykoski says. “If you do that enough, if you try to fit it into what’s known, then you have to start scratching your head, going, ‘Is this thing unknown?’ ”

Finally, earlier this year, Tykoski and two other researchers submitted a paper to the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology announcing they had identified a new species. They called it Ampelognathus coheni. In Greek, ampelos means “grapevine,” gnathos means “jaw,” and coheni is a nod to Cohen, the volunteer who made the initial discovery. This is the first new dinosaur species identified in Texas since 2010.

Cohen declined to be interviewed, but Tykoski said he often hikes in the area and brings all kinds of fossils to the museum for their researchers to clean and study. All of them help paint a more complete picture of prehistoric Texas. “There’s only a couple of us who are professional paleontologists in the region, and we can’t be in all these places,” Tykoski said. “We depend heavily on volunteers or just fossil enthusiasts who like to go out and like to fossil hunt, and the good ones who know that when they find something really potentially significant, to bring it to our attention.”

The discovery is part of a larger program at the Perot to research and catalog the expansive prehistory of North Texas. This region was once the coast of a large interior seaway, making it fertile ground for all kinds of life—but Tykoski says we’re still learning a lot about what the area now known as Dallas–Fort Worth looked like and what kinds of plants and animals lived there.

At the Perot, paleontologists, paleobotanists, geologists, sedimentologists, and more are teaming up with volunteers like Cohen to search for clues in fossil-rich soil, such as that found near the shores of Grapevine Lake. Tykoski says the site is on land owned by the Army Corps of Engineers, so the fossil is property of the federal government, but the Perot curates and catalogs all fossils found there.

Unlike in the Mountain West, where exposed soil in the badlands of Montana, Wyoming, and even as far north as Alberta, Canada, make fossil sites easily accessible, the landscape of North Texas makes dino digs a little more complicated. Not only has the region been paved over with roads, buildings, and parking lots, but the thick vegetation of our landscape makes it all the more difficult to find fossils. Plus, a whopping 96 percent of the state’s land is privately owned. For these reasons, researchers such as Tykoski often partner with local volunteers.

“We realized there were gaps in our knowledge of things happening paleontologically here, closer to North Texas,” Tykoski says. “There are some discoveries to be made and questions to be asked and answered. This is just part of the onset of a new focus, a new emphasis of our program. What’s the little story of us—what was happening in our backyard?”

Ampelognathus coheni fits into that story. Tykoski says the dino was quite small, maybe the size of a standard schnauzer. It was a plant-eater, and would’ve walked on four legs, but had the ability to stand on two to reach taller vegetation. Tykoski says scientists have found fossils of the kinds of plants it ate, as well as the kinds of prehistoric predators that ate it nearly 96 million years ago.

Since the tiny jaw is the only piece of Ampelognathus coheni that’s been found, little else is known about the species.

“We’re pretty sure this is reasonably close to adult size, our little guy here, just based on the animals it’s most closely related to, but it could have been bigger,” Tykoski says. “You never know until we find more of a skeleton.” So the next time you’re hiking in Texas, keep an eye out. You might be walking right past a one-of-a-kind fossil.

- More About:

- Critters

- Best Thing in Texas

- North Texas

- Grapevine