In Christine, Stephen King’s 1983 novel about a demonically possessed car, he drops a surprisingly poignant statement about the human experience. “If being a kid is about learning how to live,” he writes, “then being a grown-up is about learning how to die.” I have no idea what the quote has to do with the car, because I found the sentence by googling “famous death quotes,” but I do think King’s on to something. The longer you live, the more accustomed you become to the act of saying goodbye to friends, pets, relatives, and, for the sake of this article, brands.

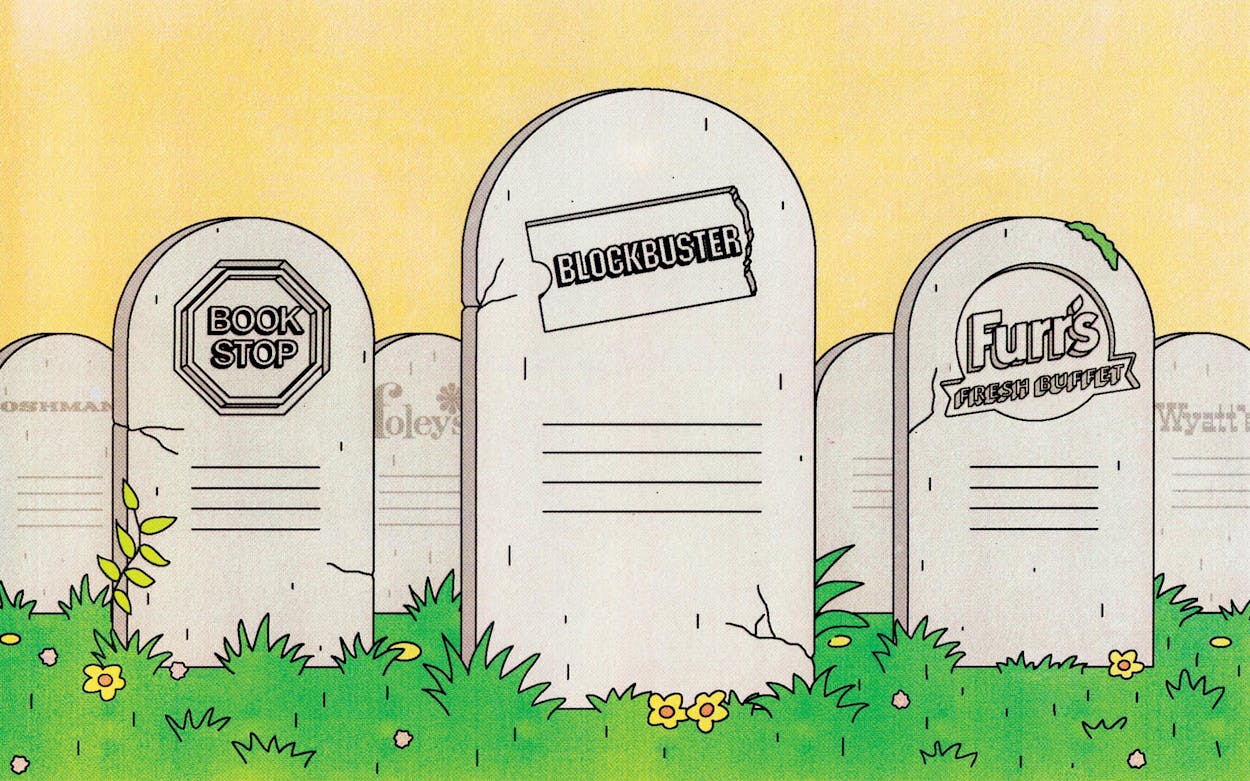

Go ahead and press play on that one Sarah McLachlan song because we’re ’bout to get to mourning. We couldn’t celebrate Texas’s iconic pickup truck models, restaurant chains, and sundry other businesses without acknowledging those that are no longer with us. Here are just some of the Texas brands to which we wish we could still be fiercely loyal. Oh, Blockbuster, we hardly knew ye.

This tribute is not intended to be comprehensive. There are surely plenty of defunct Texas brands that we forgot. Add your favorites in the comments!

Blockbuster

There are plenty among us who cannot gaze upon the combination of royal blue and lemon yellow and not think of the video rental chain that defined many a millennial childhood. The Blockbuster story begins in Dallas in 1985 and is a classic rags-to-riches-to-rags tale. At the peak of her powers in 2004, Blockbuster operated 9,094 stores on every continent except Africa and Antarctica. Four years earlier, a humble but promising startup called Netflix had offered itself to Blockbuster for acquisition, and the hubristic chain declined. We all know how that turned out. In 2010, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy. It couldn’t survive the streaming revolution, and all that’s left of the chain today is one novelty location in Bend, Oregon, and a surprisingly funny Twitter account.

Bookstop

Unlike Blockbuster, this Austin-based bookstore chain didn’t so much burn out as just fade away. The first location opened in 1982, and seven years later there were 22 Bookstops across Texas, California, Florida, and Louisiana. The chain was doing so well that Barnes & Noble bought it. Though Bookstops remained, B&N began phasing them out in the late 1990s, and they were gone by the end of the next decade. It’s a shame, because without the chain’s famous stop-sign logo, you might pass a store and know that it has books, but how will you know to stop?

Wyatt’s

Texas used to offer a veritable buffet of cafeteria chains, but only Luby’s has survived, and barely. One of the most unfortunate casualties was Wyatt’s, a Dallas-area institution that once operated more than a hundred locations across the state and up into Arkansas and Missouri. By the time Luby’s bought it out, in 1996, there were only 22 locations left, the last of which closed in 2003. Boomers don’t forget, though, and “Remember Wyatt’s?!” posts still get a lot of play on Facebook.

Furr’s

The other buffet-chain casualty, Furr’s, which opened its first location in Lubbock in 1947, lasted a little bit longer than its Dallas counterpart. It was passed around among various parent companies for a while, moving its headquarters all over the state. In 2021, San Antonio–based Fresh Acquisitions filed for bankruptcy and closed the last remaining locations. In what looks like a Pyrrhic victory, Luby’s has defeated them all, but barely.

Foley’s

Texas’s flashier department stores—Neiman Marcus, Sakowitz, Scarbroughs—got most of the attention, but for a while there we had a good crop of mid-priced homegrown chains filling our malls. From 1900 to 2006, Foley’s, a Houston company, was one such brand. It didn’t open a second location until 1961, but by the late 1980s, there were dozens of Foley’s. Nothing gold can stay, though, and in 2006, Macy’s, a famously New York–based department store chain, bought out and converted the only Foley’s left. For shame.

Oshman’s

This Houston sporting goods store, founded in the early 1930s by Latvian immigrant J. S. “Jake” Oshman, was at one time the largest sporting goods chain in the southwestern United States, with locations as far west as California. In 1978, it acquired the brand name of a little hunting and fishing outfitter called Abercrombie & Fitch, turning it into a successful mail-order business and selling to the Limited in 1988. That company would turn the clothing retailer into the preppily salacious mega-brand many of us know it as. All of this is to say: Jake Oshman was indirectly to blame for the disgusting cologne scent wafting out of every A&F location, which terrorized passersby for most of the 1990s and early 2000s. During that same period Oshman’s closed most of its stores, the last of which became Sports Authority locations in 2001. Maybe that’s just karma.

Ben Hogan Golf Clubs

According to my colleagues who are obsessed with golf, Ben Hogan was one of the greatest pro golfers ever. A Stephenville native who grew up in Fort Worth, he was one of the first top players to sell irons and woods under his name, starting in 1953. His clubs were popular among avid golfers until nearly a decade after his death in 1997. The Hogan brand then passed through a series of licensees before turning belly-up last July. The latest owner blamed supply-chain issues related to the pandemic, but Texas Monthly’s editor-in-chief has another theory of what went wrong: the things were just too durable. Exhibit A: He’s still playing with a set of Hogan irons that he acquired 51 years ago.

Whopper Burger

To Burger King fans (which we aren’t), Whopper Burger is redundant, but to San Antonians it was the name of a beloved fast-food chain. In fact, Burger King couldn’t use the name “Whopper” at its San Antonio stores until after Whopper Burger founder, Frank Bates, died in 1983, and his widow sold the company to the national chain. You can now get Whoppers at any BK in SA, but you’re better off trying a Bates Special from Burger Boy, a local chain opened by Frank’s son Carl in 1985.

Braniff International and Continental Airlines

Dallas-based airlines American and Southwest are still alive to periodically infuriate passengers, but a third major carrier that once was headquartered in the city, Braniff International, ceased operations in 1982. And Houston-based Continental Airlines faded away after a 2010 merger with United. We imagine both defunct carriers are still losing bags and canceling flights at the great airport in the sky.

Handy Andy

Texas Monthly has reported at length on H-E-B’s aggressive—and successful—efforts to crush its competitors in the seventies and eighties. One such rival was San Antonio–based grocery chain Handy Andy, which was founded in 1926 and had sixty locations operating across Texas by the 1970s. It was beloved not just for its stock and prices but for Andy himself, or at least the cheerful, bespectacled cartoon version that adorned each of the stores’ signs. Andy didn’t have much reason to be happy in 1981, though, when the chain declared bankruptcy after a failed attempt to open nine gourmet food stores in Houston.

- More About:

- Business