Last week, I threw myself into my usual post-Thanksgiving ritual. I put away the silver and china, washed and folded three or four substantial batches of laundry—sheets, towels, napkins from a dinner for twenty—and tried not to think about the looming Christmas prep. Then, finally, I tackled our son Sam’s room, which I straightened and tidied so that it looked again as it did when I straightened and tidied it before he came back to Houston for the November holiday—his first visit in two years because of COVID-19.

Before Sam arrived from his adopted home in Philadelphia, in fact, I had spent a few days converting his former space back into a bedroom from its more-recent status as a storeroom, shoving my sweater boxes under the bed and on high shelves in his closet, moving a six-foot feather duster and a stepladder from behind his bedroom door to behind my home-office door. The trophies and Harry Potter editions on his bookshelf still indicate that a boy once lived here. But at thirty, Sam hasn’t been a boy for a long, long time.

It doesn’t take a therapist to see that this incessant straightening, this reestablishment of our current childless order, is a form of pain relief. There is no way around the fact that my once reedy, talky, auto-obsessed kid is now a full-grown man with a career and a partner he loves. On this visit, Sam even seemed a few inches taller than I remembered (“Y’all have shrunk,” he suggested to me and my husband, in response to my observation); and has gone all-in on a sartorial style that would make my late, Brooks Brothers–devoted father blanch. Sam has his own opinions that do not always track with ours (“I could never live in Texas with politics like these”) and future plans that do not include us. “Maybe we could meet you in Rome,” I think but do not say when I hear of a spring trip he’s putting together.

When Sam was away at college in New York, I was forever cracking jokes about how often he was back home in Houston. There was fall break, winter break, spring break, and so on, with lots of long weekends in between. I could remain oblivious, or in denial, about the time when those visits would drop off, coinciding with the intervention of real life—his, not mine.

No one tells you that the real empty nesting coincides not with a college acceptance but with the successful launch of a child into the adult world. “Well, you wouldn’t want him still living in his old room,” my husband said once, when I confessed to wanting more face time. I agreed, but I can’t say it was easy.

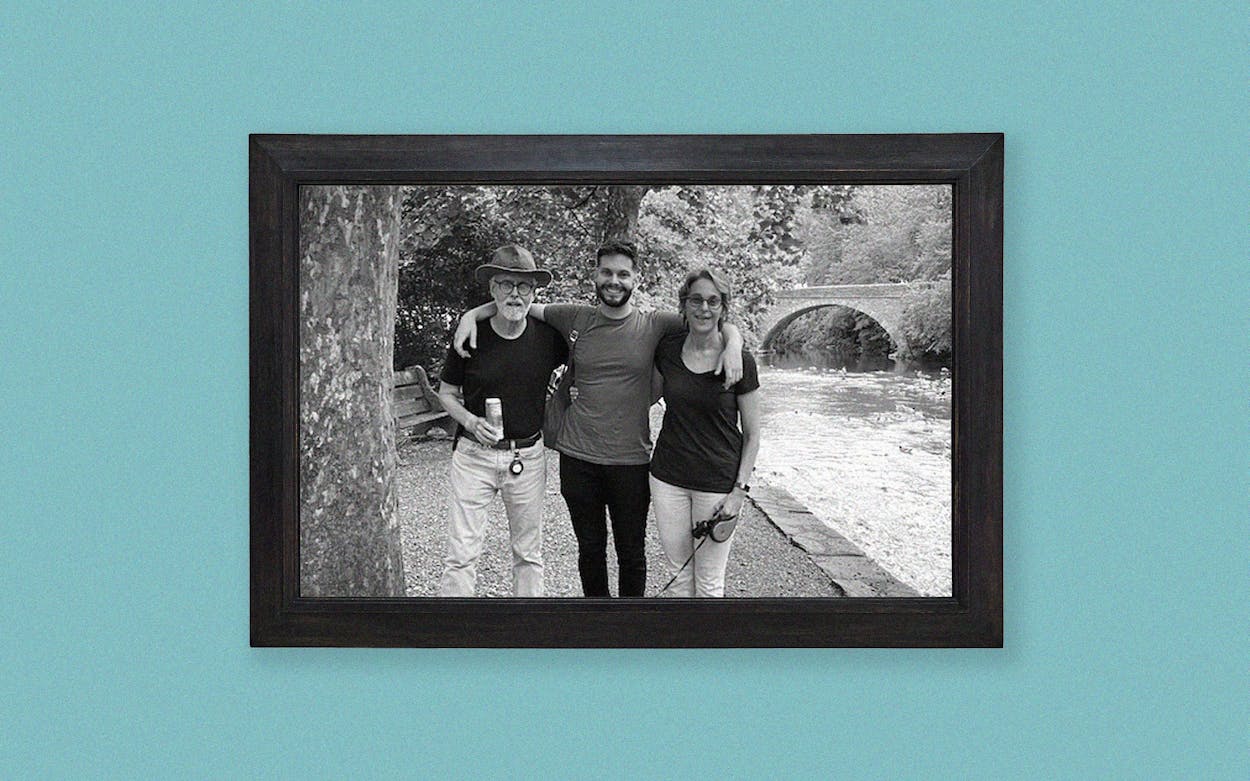

So now our lives are made up of these abbreviated visits, the two or three times a year (in non-pandemic times) in which Sam notes the changes in his parents and we note the changes in him and try to maintain the emotional infrastructure that keeps us together. I say “us,” but in recalling my own youth and my own parents I understand that this is a pretty one-sided job: at thirty I was too busy building my own life to sense any loss they felt when I had too much work to come home for a weekend or couldn’t face toting nearly a ton of baby baggage the two hundred miles to San Antonio.

But the shoe is on the other foot now, as my mother used to say. A photo carelessly shuffled into a stack of lists and receipts on a kitchen counter afflicts me with an acute case of melancholia: there is Sam at five wearing a game grin and a striped shirt of a soft, faded cotton I can almost feel between my fingers so many years later. The frame is made of stamps from around the world, one of a hundred kindergarten projects. I found myself wishing I could remember the day Sam brought that gift home to me, the circumstances of that quotidian afternoon lost because, surely, I was rushing to get dinner on the table and to get bath time and book time and bedtime over with to keep Sam on a schedule and to snatch for myself a moment’s peace before starting all over again the next day.

“Part of love is holding on, and part of love is letting go,” a wizened friend once told me, advice that delineates my parenting from that of my parents, who were better at the first than the second as I grew up and away. My mother in particular was forever demanding proof of primacy, which inevitably led to the opposite, and a lot more drama than anyone wanted on holidays. (What college kid doesn’t escape the family bonds after dinner to meet up with old friends until way past midnight? Well, I know of at least one who couldn’t.)

For that reason, I have always wanted Sam’s visits to be easy, though there are all sorts of questions I want to ask. Do you know the best way to the grocery store? How can you read in the dark like that? Are you taking care of yourself? Are you happy? Will you love me even if you don’t need me?

Instead of upping the dramatic ante, I ask my son to spot me on a ladder while I clean off some alien-looking grime on an air conditioner before company comes. (“Want me to do it?” he asks, a portent if there ever was one.) He puts a baseball hat on the dog and takes a photo; he lists all the restaurants he wants to revisit, and we make it to none of them. Sam and his partner, Brian, clean the back porch with a willingness and enthusiasm I can only attribute to the latter’s influence. They leave the house after dinner to meet some of Sam’s old friends, and I try not to wait up for the sound of the car pulling into the gravel driveway. When neighbors and old friends drop by, Sam seems as unfazed by their love for him as I am moved by it, and when he tells me, “I like the scrambled eggs we make the best,” a part of me quiets for the first time since he got home.

This is what good parenting looks like, I tell myself, a disciplined concoction of faith and trust, of love that is constant but lightly worn. We all had a wonderful holiday, the kind a lot of families can only dream of. Who would want more? I asked myself the day of Sam’s departure. By then the Thanksgiving dishes had been put away, his bags were packed, and he was hunched over his phone, scrolling and connecting with people I do not know, setting up this agenda and that, lost in the reverie of his life thousands of miles away.

Picturing an empty room, I asked, “What are you doing for Christmas?”

- More About:

- Houston