On a brisk day in January, hunter and trapper Robert Lyle is opening the gate to the Willamar tract of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, a 1,162-acre brushy patch of federally protected land near Port Mansfield, when another pickup pulled up behind Lyle’s Chevy Silverado. “You with the oil patch?” the driver asked Lyle.

“No,” he said. “I manage the hogs.”

The stranger paused. “Can you do that?”

“Well, we try,” Lyle chuckled.

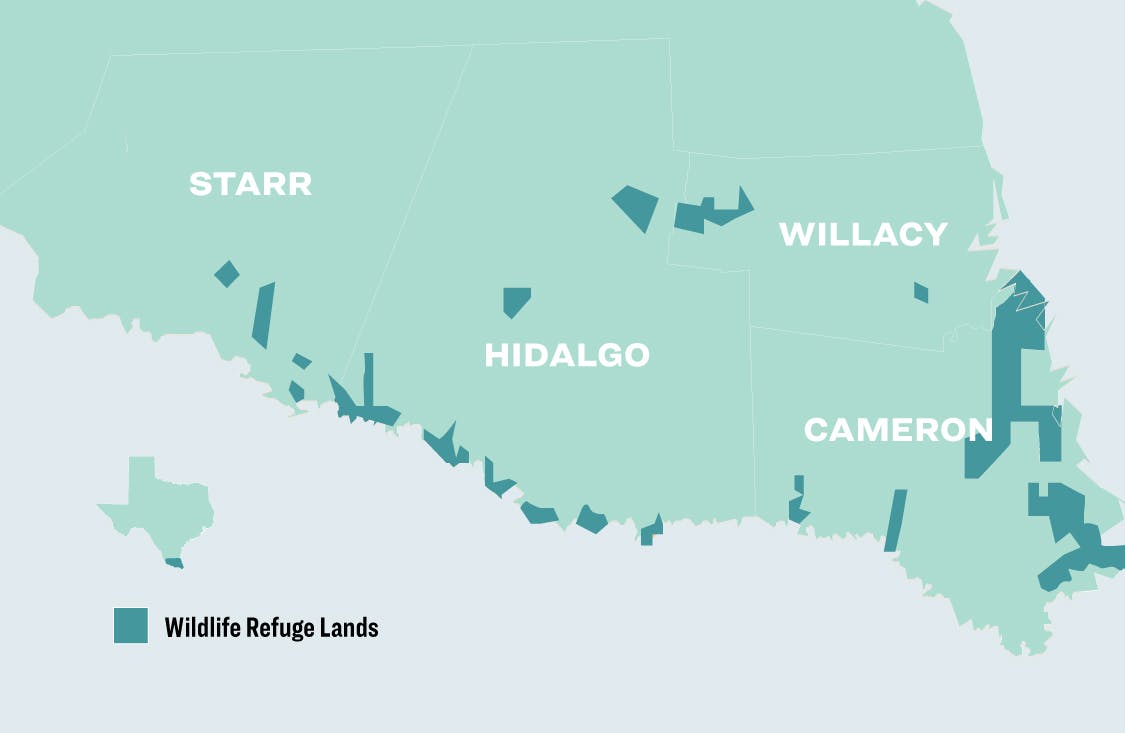

Since 2014, Robert and his wife, Vickie, have been the only trappers allowed year-round on the 140-plus national refuge units sprinkled across the Lower Rio Grande Valley, and they also hunt on private land from the border north to Sinton and as far west as Laredo. They bag an estimated thousand hogs a year, butchering the pigs on-site and processing the meat themselves at their home near Mercedes. Robert says his biggest expense is butcher paper, and with two freezers full of hog meat, from summer sausages to spareribs and sirloin steaks, it’s clear he needs a lot of it.

The Lyles work for free under a special-use permit with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the federal agency that oversees the string of wildlife refuge areas that preserve some of the last bits of the scrubby forest that once covered this part of South Texas. Whenever there’s a hog infestation on one of the wildlife parcels, the Lyles’ supervisors at the FWS dispatch the couple to take care of the problem. Their permit, renewed yearly, requires them each month to mark the weight, sex, and number of hogs they kill. Because the federal agency doesn’t survey the number of hogs on its properties, the FWS relies mainly on Robert’s records to keep track of hog activity.

“These wildlife refuges are for native animals, not exotic animals,” said resident FWS biologist Imer De La Garza, “so for us, control is not seeing so many of the signs that mean hogs are living here.” The goal is to minimize the number of feral hogs on sensitive parcels so that native animals face less competition and fragile ecosystems have a better shot at recovering. There used to be other trappers combing through federal land in the Rio Grande Valley, but Imer said they just weren’t killing enough hogs. “Nobody else treated it like a full-time job.”

Even when they aren’t in the field, Robert and Vickie keep tabs on live game camera footage on their phones, waiting for the right moment to trigger trap doors on their hog pens with the push of a button. When working on private land, Robert charges about $400 per hog killed and uses that money to make up for the time and effort he puts into trapping for free. He considers the work he does on federal land a public service, even donating the meat he collects to local nonprofits, food banks, and orphanages in the area. “I just think it’s what matters,” he said.

Willamar is bordered by ranches and hosts a small natural gas operation. It’s also teeming with hogs—big ones, Robert Lyle told me, based on the size of their tracks and the mud they’ve rubbed on the trees, as high as four feet up the trunk. They’re unaccustomed to humans and oftentimes aggressive.

Willamar is bordered by ranches and hosts a small natural gas operation. It’s also teeming with hogs—big ones, Robert Lyle told me, based on the size of their tracks and the mud they’ve rubbed on the trees, as high as four feet up the trunk. They’re unaccustomed to humans and oftentimes aggressive.

Before exiting his truck, Robert told me to look out the window for hogs.

“Startle a pig and he’ll attack,” he explained. “They only run away when they’ve thought about it.”

We set out on foot to check Robert’s feeders, several four-foot PVC tubes filled to the brim with corn feed. The tubes, tied loosely to the base of a T-post that Robert and his wife planted earlier in the week, have holes drilled in their sides, which forces the hogs to roll the cylinder around with their snouts to shake loose food, leaving behind signs of activity on the ground.

Robert gives me a lesson in hog trapping. The key is to slowly introduce yourself into their routines. “It’s about gaining their trust,” he said. About a week after Robert and Vickie put out the bait, they return to the site to check for trampled pathways in the grass, tracks, droppings, and other “sign” that might indicate hogs rather than deer, raccoons, or other critters. The Lyles’ preferred bait is dried corn feed, but depending on the season and the presence of other foods, they sometimes soak the corn in water and sugar. They’ve even resorted to sugary pastries. “Hogs have a sweet tooth,” Robert said, which they acquire from eating foods like mesquite beans.

If there is evidence that the hogs have come around, the Lyles then set up either a box trap or a corral around the bait so that the animals get used to entering and exiting the trap. A game camera keeps watch over the scene. Whereas a corral surrounds a larger area with fencing and can trap several dozen hogs at a time, a box trap is just what it sounds like: a metal box that can trap seven or eight at once.

Hogs that don’t know any better can be captured quickly once they’ve adjusted to the presence of the trap, but trap-wise hogs may cry out to warn their brethren of danger. Robert said hogs have also been known to use raccoons as an “early warning system,” essentially waiting to see if the trap closes before they themselves enter to eat.

Early on, the Lyles realized that the hogs sniff feeders and even nearby cameras for the smell of humans before letting their guard down. So the couple now wear boots and gloves when handling equipment or tossing dead hogs into the back of their Chevy Silverado.

In areas where they’re hunted, hogs have become nocturnal; in areas where they’re not, they’ve become more aggressive. Robert says hogs are opportunistic omnivores; when they can’t find their usual roots, nuts, or mesquite seeds, he’s seen them turn to snakes, birds, and even fawns and livestock for a meal. In some areas, rattlesnakes have adapted to predator pigs by staying silent when hogs are near—the rattle can be an invitation to a snaky lunch.

The animals have also adapted to nighttime spotlighting by dropping to the ground and hiding under the brush, Robert added, and they’re getting bigger too.

“A lot of people will tell you a boar’s tusks rarely get to be four inches,” Robert said, “but we’ve seen up to twelve.”

There lies the rub when it comes to curbing the infestation of hogs: they’re smart, often outwitting those who hunt them. But the Lyles understand just how quickly the game can change and adjust their tactics accordingly. They may be able to use the same trap in the same area a couple times before the hogs catch on. But the fronts are always moving, and no single method can keep the animals from expanding their territory and eluding capture.

When Spanish colonizers brought hogs to the Americas, they had no idea how quickly the invasive species would spread. Neither did the wealthy twentieth-century ranch owners, who imported Eurasian wild boars for sport hunting and caused an explosion in the crossbred population. Wherever the hogs went, they brought diseases—including swine brucellosis, which causes infertility in cattle and other livestock—and disrupted fragile ecosystems, contaminating water, squeezing out wildlife, and causing millions of dollars in damages. They can be found in 253 of Texas’s 254 counties, according to Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. The number of states reporting the presence of wild hogs has more than doubled since 1989; it seems the problem is only getting worse.

There are hundreds of thousands of dollars tied up in reforestation projects on federal refuges where Robert and his wife are permitted to trap. Acres of planted trees, when left unguarded, make for an easy snack for the hogs roaming the area. There are also endangered species, like the Texas burrowing owl, whose nests hogs dig up for a quick meal. In an effort to dissuade them from spreading into other parts of the refuge and threatening these species and the trees, Robert and Vickie butcher the pigs just down the road from their traps, throwing the meat in a cooler, and leaving the carcasses where the hogs can find them. They’re less likely to pass into an area where they know their kind’s been killed.

The last trap we visited was just off the main footpath. I asked Robert why he chose this spot instead of pushing deeper into the brush. He told me to follow him. We ducked under the branches and stepped into a marsh where all sounds seemed to stop. The hogs had rooted the grass on the edge of the marsh until it was completely bare. They’d dug holes and tainted the springwater with dirt and feces. Robert told me this is where they sleep, mate, and eat.

Eradication is likely impossible, but a sort of stalemate can theoretically be reached. To keep populations in check across the state, about 70 percent of the animals (roughly 1.5 million hogs) need to be killed every year. (Right now, hunters and trappers, including Lyle, estimate that they kill roughly 450,000, or about 30 percent, which is far from the stalemate they hope to achieve.) Hogs are capable of breeding after just nine months of life, and the average litter is around five or six piglets. Keeping their population in check requires constant trapping, hunting, and coordination among neighbors, counties, and the state.

There’s a future in which people will manage and control the hog population on small pockets of land, Robert said, “but there’s not a future where hogs aren’t most everywhere.”

Recently, the state of Texas has loosened regulations to allow for more boots on the ground. In 2019 the Legislature permitted night shooting and allowed adults to kill hogs without a license, which has attracted tourists from across the country. Bolstering the hunting tourism industry, however, has also created an incentive for landowners to keep the hogs around and even, in some cases, breed them in captivity. Robert said it’s illegal to transport hogs without a permit. But he knows of people who do it anyway, fattening them up for canned hunts. And for every hog fed and released, there are at least a few who get away, as Robert says, “spreading pigs to more areas where they wouldn’t be otherwise.”

The sheer number of hogs, and their ability to adapt to threats, makes them seem almost invincible. But Robert isn’t discouraged. What motivates him to keep fighting a losing war?

“The good taste,” Robert said.

- More About:

- Hunting