In an ignored corner of our bedroom, atop some dusty books, sits a small statue of a stallion made of copper. It’s about five inches tall, accessorized with a built-in Western saddle and bridle. The horse’s bit is a beaded chain, the kind you often find attached to a rabbit’s foot good luck charm. I think I bought the horse more than fifty years ago in what was then the souvenir shop of San Antonio’s Menger Hotel, where my parents met friends for drinks around the pool on Sunday afternoons.

The stallion became part of a collection, my “stable” of around one hundred steeds, many purchased with my allowance at a toy store in North Star Mall. As the only survivor of those days, he is somewhat worse for wear—two of his legs show scars of emergency surgery with Elmer’s glue. But at least no one had to shoot the poor thing to put it out of its misery.

I can’t tell you why or how this particular remnant of my past has managed to survive the decades, only that when I do take the time to pick it up and hold it in my hands, it has the effect of Proust’s madeleine, conjuring up a childhood that seems centuries instead of decades away from the time and place I live in now. I often wonder what today’s urban Texan, who can fly nonstop to Europe from some of our cities, who can have Indian pizza for lunch and tofu barbecue for dinner, and whose kids can learn Mandarin in public school, would make of the place where I grew up. In the early sixties, San Antonio and Texas were still so isolated from the rest of the country that for me a shopping trip to Neiman Marcus in Dallas was the height of glamour, and a cabrito lunch at the Cadillac Bar, in Nuevo Laredo, was a noirish adventure. The opening of the Astrodome in 1965, with its soaring domed roof and rainbow-hued seat sections, was as miraculous as any Apollo space flight. (Back then, the only route to Houston was U.S. Highway 90; the section of Interstate 10 that runs between the two cities hadn’t been finished yet.)

We lived amid Texas history, mostly taking it for granted. Places such as the Alamo were such a part of our daily lives that we were nearly oblivious: sometimes, while my parents were partying at the Menger, my brothers and I would steal over to it next door, not to ponder the deadly battle that took place there, but to marvel at the number of stray cats inside its walls. Does any of this matter, beyond the wonder anyone feels while marking the passage of time? Sure, understanding where you came from is usually helpful in figuring out who you are. But for Texans inculcated with a particular brand of exceptionalism—that’s a lot of us—questions of identity are all about losses and gains, and what we carry with us into the future from the past. At those times, a tiny copper statue can take on a surprising weight.

My relationship with Texas has always been seasoned with more than a pinch of ambivalence. I was never totally sold on Texas exceptionalism. For one thing, I had spent enough time on the playground to understand that the kids who bragged the most turned out to be the biggest fraidy-cats whenever real courage was called for.

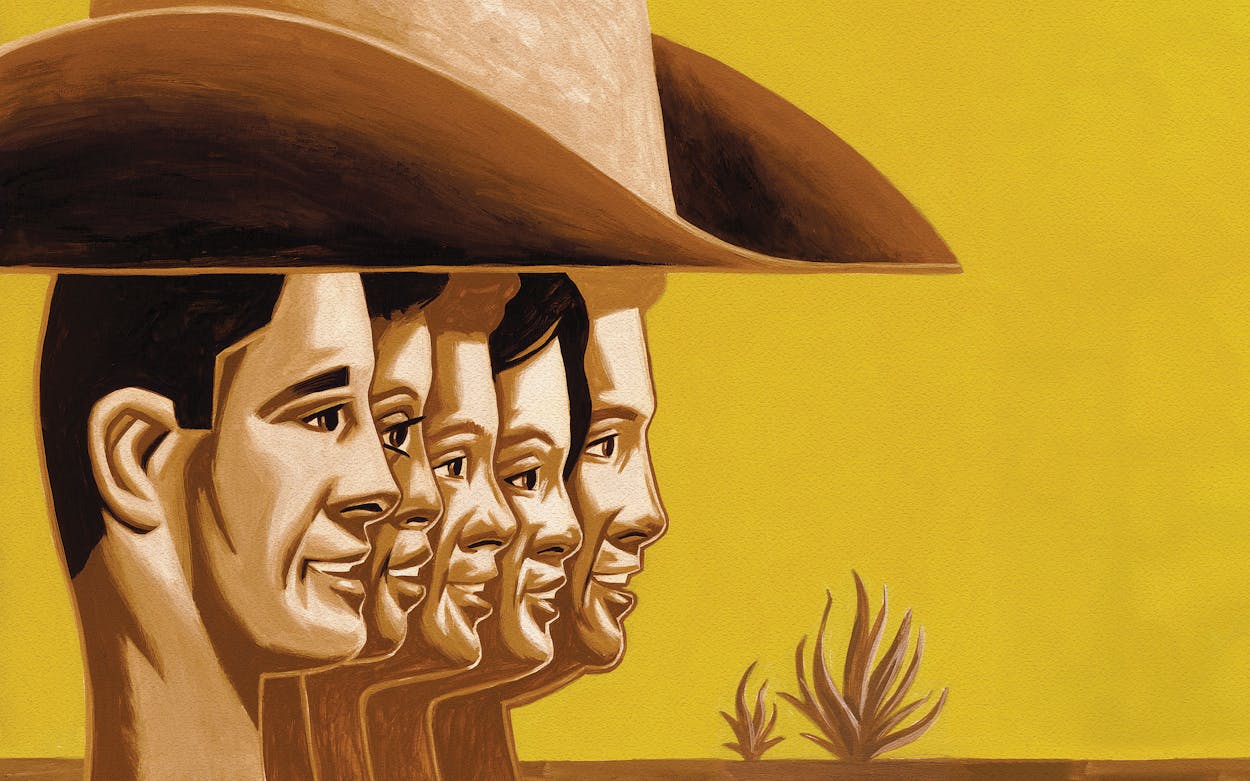

Sure, we Texans had been shaped by all that empty space—and by surviving wars, rattlesnakes, scorpions, floods, droughts, hurricanes, and tornadoes in order to carve out a piece of it for ourselves. So yes, of course we resented anyone who tried to tell us what to do, because we had been doing for ourselves for so long. But we weren’t riding buckboards into town anymore, and the contradictions in the mythology were pretty obvious, even to a kid. Some Texans were strong and silent, but others were big braggarts and tellers of tall tales. We were friendly, warm, and generous—never met a stranger—except, too often, when we confronted people who weren’t like us or who had something we wanted. We demanded the freedom to roam the land at will—until we got some of it for ourselves, at which point some of us staked our claim by any means necessary. And yes, Texas men were tough and fearless—muy macho—but it always seemed that Texas women were the ones who cleaned up the messes the men made.

Some of those contradictions posed harder questions: why, if Texas was so rich, I wondered as a child, were so many people still deprived of a decent education and opportunities to advance? Why was it okay to show off wealth but not, in some circles, education? For that matter, why did high school football matter more than English class? Why were the Latino kids in my public school exiled to the back of the classroom? Why did so many people complain about the federal government butting into our business—unless Washington was funding DFW International Airport or handing out tax breaks to oil and gas companies or parking the space program in the home state of then–vice president LBJ? Somehow, all that emphasis on freedom in my seventh grade Texas history class meant that nobody had to do anything about the rutted caliche roads and listing shacks on the West Side of San Antonio.

That poverty was as durable as the limestone mansions dotting Olmos Park. In his 1968 testimony before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, the Catholic priest Ralph Ruiz noted that 28 percent of San Antonio families earned less than $3,000 a year and more than 6 percent of them earned less than $1,000. (That’s about $27,000 and $8,900 in today’s dollars.) Children went hungry every night on the West Side. “Although the economic picture appears optimistic and growth seems to be certain,” he stated, “it is still true that San Antonio has more area of blight than ever before. We have before us then two San Antonios: one, a San Antonio growing in prosperity and economic viability; the other, a San Antonio which has grown only in the intensity of its problems.”

Little action had been taken two years later when the mayor, Walter McAllister, infamously explained away our problems to NBC News by saying that Mexican Americans weren’t ambitious but were well-suited for jobs as maids, restaurant workers, and gardeners. By the time I was heading out of state for college in 1972, I was sure I’d never return to a place whose leaders could be so boneheaded.

But four years in New England, where the frigid winters served as a metaphor for the culture, and supposedly smart people asking me how far I had to drive to get to an airport from San Antonio, had me reconsidering. And though I couldn’t admit it to myself at the time, I was desperately homesick for my family, for the warmth of the sun and the people, for the comforts of a Number 3 platter. My mother’s side of the family had been in Texas since before the Civil War. Who could say I didn’t belong?

A lot of other people were feeling the same way in the mid-seventies; we wanted to live in a Texas that merged the best of the old with the best of the new. In 1940, 55 percent of Texans lived in rural areas. But within ten years, that number had shrunk to 37 percent; by 1970 nearly 80 percent of Texans lived in the cities. And nonwhite residents’ strength was beginning to coalesce in San Antonio, where community organizers such as Ernesto Cortes and a new city councilman named Henry Cisneros had managed to break the grip of the Anglo power structure, portending Texas’s transformation into a majority-minority state.

Houston was changing even faster. With the price of oil jumping from $24 in May 1973 to a whopping $63 in January 1974, the oil boom was on, and the place began to draw people not just from Dilley but also from Denver and Delhi and Dubai. Provincialism appeared to be dead and buried. Newsweek and the Atlantic published cover stories about how amazing (amazing!) Texas in general and Houston in particular had become. (The former cover featured a close-up of a beaming Kilgore Rangerette, which wasn’t the image of change I would have chosen.) Houston was the place where a snotty, East Coast–educated 23-year-old Texas girl—a.k.a. me—could find great bookstores and restaurants that served falafel and bibimbap and at the same time enjoy the traditional Texas pastime of watching the antics of people who then qualified, with their mere millions, as the superrich. Back then, oilman Oscar Wyatt was shooting feral hogs from his helicopter while his wife, Lynn, was entertaining Princess Grace at home on River Oaks Boulevard. In the eighties, apartment king Harold Farb spent $6.5 million to build himself a supper club where he could perform his beloved show tunes and $20 million to divorce his first wife ($19 million and $60 million in 2023 dollars). These were people who, let’s just say, were not afraid to be themselves.

By the eighties and nineties, the archetypes had shifted, but they sure hadn’t gone away. The silent, solitary cowboy had morphed into Jett Rink, the silent, solitary wildcatter of Edna Ferber’s Giant, who then morphed into the somewhat less silent and solitary entrepreneur—still a risk-addicted individualist, but with a Harvard MBA, bespoke suits, and intimate knowledge of the best dining options on the Left Bank. Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling was one of those guys at the turn of the millennium, a man whose personal boom-and-bust cycle included starring as a business-media cover boy and then, not much later, as a convicted felon. He’s out of prison now, and if Houston’s forgiving history is any guide, just one deal away from being welcomed back into proper society. That Enron collapsed so spectacularly and yet so many of its executives rose from the ashes to grow still richer is a twenty-first-century update of a very familiar oil patch theme.

Generations of Bushes even played the part. Despite his Skull and Bones background, 41 was a genuine wildcatter, dragging his family to dusty Midland to build a modest fortune in a pursuit that back then was far from a sure thing. And for better or for worse, 43 showed his West Texas roots in his lack of pretension (he really was friendlier than Ann Richards up close) and in his (sometimes misguided) faith in his own instincts. “I’m not a textbook player, I’m a gut player,” he once told Bob Woodward. (Yes, in Texas even some Yale grads married to librarians have to pretend they don’t read.) In fact, if you google “George W. Bush” and “cowboy,” you get more than 1.3 million results, and a few aren’t even pejorative.

The mythology of Texas exceptionalism persisted because it wasn’t all mythology. A person could still come here without money or social connections and make a go of it with better odds than could be found elsewhere, and many did: Texas was the fourth-largest state by population in 1970; by 2020 it was the second largest. Houston was the sixth-largest city in the country in the seventies; now it’s the fourth and breathing down Chicago’s neck. Over the past decade, we’ve added more people than any other state, and we’re the second most diverse, trailing only our eternal nemesis, California. Few call us rubes anymore. Tourists come from Shanghai and Stockholm to see the Menil Collection. (And, yes, to eat barbecue.)

But a funny thing happened on the way to urbanization, prosperity, and respect. A lot of the problems that festered when I was growing up here are still with us, and some have grown worse—a situation that could be attributed to various leaders’ fundamental beliefs. The federal government is still the enemy, at least rhetorically—even though Texas receives some $28 billion more from Washington each year than it contributes in federal taxes. The Legislature has consistently said no thanks to billions in Medicaid funds that could provide health care to poor children and their families. According to a report released by the Annie E. Casey Foundation last year, Texas ranked forty-fifth in the nation for overall child well-being, forty-eighth in child health, and thirty-third in education. In 2019, 70 percent of Texas eighth graders weren’t proficient in math, while 70 percent of fourth graders weren’t proficient in reading—both worse than the national averages. Don’t even ask about the number of uninsured. (Okay, we’re first in the nation.)

After a brief flirtation with reform and innovation under Ann Richards, the Texans who fund and elect our leaders came to prefer protection of wealth and advantage over expansion of opportunity. As Texas Monthly’s great political chronicler Paul Burka wrote on the eve of his retirement in 2015: “I wish I could say in parting that the twenty-first century has been good for Texas politics, but I can’t. If Texas politics once produced giants, our time seems more like the dark ages. There are no John Connallys or Ann Richardses or Bob Bullocks. These were people who loved Texas and, because of that love, knew how to reach across the aisle, set their egos aside, and put the best interests of the state first.”

In contrast, Texas today seems pulled in two directions, with so many issues used simply as an occasion for argument instead of compromise, for broadening divisions, not just between political parties, but between Texans. I know I grew up at a time when those divisions were less apparent because one group held all the power, and that I now live in a different time and a different Texas, where the concept of sharing power—for the greater good—has been met too often with suspicion, if not outright hostility.

Our mythology has always claimed that Texas is big enough for everyone. The time has come for us to prove it.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “My Texas, Then and Now.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- San Antonio