This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There was an idyllic quality about Galveston in the latter part of the nineteenth century, a sort of Toy Town mystique that suggested life was a party that went on forever. It was a distinctly cosmopolitan city, one of the largest and the wealthiest in Texas and one of the wealthiest in the country. The Strand, known as the Wall Street of the Southwest, boasted 26 millionaires in a five-block span. Galveston’s Grand Opera House was a miniature version of the great opera houses of Europe, and its port led the United States in cotton exports. The word “prosperity” seemed to have been invented to describe Galveston.

At times the mystique of Island living overwhelmed the senses. This place could have been just south of Eden. Temperatures on the Island were considerably more comfortable than they were on the mainland. Ducks and geese were so dense that when startled they blotted out the sky. One hunter told of killing 32 mallards with a single shot. Oysters, plump and snug in their shells, littered reefs like stones in a boulder field. Islanders gathered them in barrels and roasted them on the beach.

Most of the city’s upper class lived on Broadway, a boulevard of elegant homes set along an esplanade of oaks, oleanders, and imported palms. Streetcar tracks ran down Broadway, and at night the Island’s gentry sat on their galleries and watched the so-called pretty cars strung with multicolored electric lights and filled with young people singing and laughing. Broadway was the highest point on the Island, 8.7 feet above sea level, a sort of continental divide. From there the Island tapered down to the bay and the Gulf of Mexico, where the distinction between sea and land was measured in inches.

Islanders had a cavalier attitude about hurricanes, regarding them at worst as inconveniences and at best as opportunities for cheap thrills. Most adults had lived through their share of hurricanes. There were three big blows in 1871, washing a schooner and three sloops up Nineteenth Street and partially destroying St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, but when damage was assessed at the end of the season, only four lives had been lost. Tides from the 1875 storm measured thirteen feet above normal and covered the entire island. That same storm struck with lethal fury just down the coast, sweeping away three fourths of the port town of Indianola and killing 176 people. But Indianola was on the mainland, not the bay. What happened there in 1875 seemed to prove what Islanders had maintained all along—that only when a storm surge hit a solid object like the mainland was there likely to be major damage. If a similar storm hit Galveston, Islanders assumed that the bay would absorb the shock.

Eleven years later they apparently were proven correct. A storm in 1886 completely destroyed Indianola; those who survived moved away and the town was never rebuilt. Meanwhile, in Galveston the storm blew off a few roofs, flattened some fences, and as usual, washed away the Strand’s wooden paving blocks. Afterward, there was some discussion about building a seawall, but no one took it seriously. On the contrary, Islanders assumed that Galveston had stood up against the worst that nature had to offer.

Friday, September 7, 1900, started out oppressively hot and then turned into one of those seemingly perfect days when the wind swings around and blows out of the north and the heat of summer starts to retreat. Frayed strings of clouds stitched a satin-blue sky, promising the relief of rain. Long swells broke on the beach, and young sports who should have been tending to business on the Strand took off early to frolic in the breakers.

Isaac Cline saw the surf, too, but wasn’t amused. Cline, the chief of the U.S. Weather Bureau in Galveston, had been plotting a storm that had started days earlier in the Cape Verde Basin, off the western coast of Africa. Swept along by the easterly trades, the storm had blown just north of Cuba on Tuesday. By Thursday it had passed through the Straits of Florida and was traveling across the Gulf of Mexico in a northwesterly direction, headed toward the Texas coast. On its present course the storm would likely make landfall well to the east of Galveston, which would put the Island on the comparatively safe backside of the vortex. Cline dutifully hoisted storm-warning flags.

Later in the day Cline walked along East Beach, feeling uneasy and trying to sort things into logical order. He was a practical man, a scientist and a physician, and he had a low tolerance for inexactitude. Something didn’t add up. The barometer was falling slowly, as one might expect, and the wind was blowing out of the north at a brisk 15 to 17 miles per hour. And yet the tide was four and a half feet above normal and rising; it had already inundated the Flats, on the Island’s east end. That was what worried Cline. The tide was rising even though the wind was blowing directly against it. Normally, a north or offshore wind meant a low tide—on such occasions, Islanders joked that you could walk halfway to Cuba. Cline had never before observed the phenomenon of high water with opposing winds, but he knew its name: It was called a storm tide.

Cline had been with the weather service for eighteen years, eleven of them in Galveston, and in all that time the only severe hurricane to hit the Gulf Coast was the one in 1893 that drowned two thousand people on the Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama coasts. The 1886 hurricane that wiped out Indianola was a trifle by comparison. In 1900 there was little information available on the habits of tropical storms, but Cline knew that under the right conditions, they were capable of devastation beyond belief. The sixteen-foot storm tide that swept over the Ganges Delta and blasted Calcutta in 1864, for example, drowned 40,000. All that afternoon Isaac Cline and his brother Joseph, who was also a meteorologist with the weather bureau, distributed information about the storm’s movement and warned people to move away from the beach.

Rain started just after midnight and fell steadily all night. At one o’clock in the morning Joseph Cline finished up at the bureau and went home to bed. Joseph lived four blocks from the beach, in Isaac’s two-story frame house at Twenty-fifth and avenue Q. It was a sturdy house, constructed to withstand any storm in memory, and it was raised on pilings well above the high watermark of the 1875 hurricane. Nevertheless, Joseph slept fitfully until four, when some “sense of impending disaster” awakened him. He went to the south window and looked out. In the few hours he had slept, the back yard of the Cline home had become part of the Gulf of Mexico. “I shook my brother awake and told him that the worst had begun,” Joseph Cline said.

By nine o’clock rain was running calf-deep down the street in front of Louisa Rollfing’s house a few blocks from the beach. Everyone in her neighborhood was having a great time. Children and even a few housewives removed their shoes and stockings and waded amid driftwood and clumps of seaweed. Near the beach, waves crashing against the streetcar trestle shot into the air as high as the telephone poles. Everyone was having fun until someone came up from the beach and told them that the bathhouses were breaking to pieces. “Then it wasn’t fun anymore,” Louisa recalled. Louisa’s husband, August, was working with a paint crew downtown, and she sent her eldest son by streetcar to tell August to come home immediately. Her son reported back later with this message: “Papa says, ‘You must be crazy,’ he will come home for his dinner.” Water was already coming in over the doorsill. Louisa began packing.

Two competing forces were tearing at the island. Far out at sea the storm was piling up walls of water and pushing them toward shore, while on the mainland a north wind was pushing in the opposite direction. The tide had forced itself steadily into the harbor, raising bay waters six feet, and the north wind drove angry brown waves against and over the wharves and railroad tracks. By one in the afternoon the wagon bridge and the three railroad bridges across the bay were all submerged. If anyone had thoughts of escaping to the mainland, it was too late.

Rabbi Henry Cohen was returning from temple when he noticed a long exodus of people moving up Broadway from the east end, carrying odd pieces of household goods and armloads of clothing. His home on Broadway had always been a sanctuary in times of crisis. But Cohen wasn’t worried; there was no record of a flood tide that had seriously threatened Broadway. Though the rain was pounding down and the sky was as dark as twilight, the rabbi observed among the refugees something resembling a holiday mood. Children ran ahead, sliding on the mud slicks. The rabbi found spare umbrellas and blankets and passed them out, and Mrs. Cohen gave apples to the children.

Mollie Cohen finally persuaded her husband to come inside and put on some dry clothes. The electricity was off, and they sat down to lunch by candlelight. “We had a storm like this in ’86,” she told her children as they ate. “My father’s store on Market Street was flooded.” At that moment a gust of wind shook the house, causing plaster to shower from the ceiling. “It’s just a little blow,” she tried to assure them. Presently, the rabbi went to the door and looked out. He couldn’t see the boulevard through the dark curtain of rain, but he could see water lapping over the first step of his front porch. “It looks as if the water has reached Broadway this time,” he said, gathering the children and steering them away from the door. “Come in the parlor, Mollie, and let’s have some music.”

August Rollfing had finally realized the seriousness of the situation and sent a wagon from Malloy’s Livery Stable to fetch his family and take them to the home of his mother on the west end. “It was a terrible trip,” Louisa Rollfing recalled. “We could only go slowly for the electric wires were down everywhere, which made it so dangerous. The rain was icy cold and hurt our faces like glass splinters, and little ‘Lanta’ cried all along the way. I pressed her little face hard against my breast, so that she would not be hurt so badly.” By the time they reached Fortieth and Avenue H, their horse was up to his neck in water. They were only a block from their destination, but when they tried to turn down Fortieth, a man shouted for them to stop. “You can’t get through,” he said. “There’s a deep hole ahead.” Louisa made a desperate decision: Their only hope was to try and reach her sister-in-law’s home at Thirty-sixth and Broadway.

In the tower above St. Mary’s Cathedral, the statue of Mary, Star of the Sea, began to lurch and sway. The statue had been erected to watch over the Island after the 1875 storm, and now it threatened to come crashing through the ceiling and crush the people who had taken refuge beneath. The lower apartments of the rectory had already flooded, forcing Father James M. Kirwin and other priests and members of the household staff to move to the second floor. The cathedral and the rectory seemed about to disintegrate. Windows exploded. Cornice work tore loose and rambled along the seashell pavement like concrete tumbleweeds. Father Kirwin observed, “Slates from roofs were flying more thickly than hail and more deadly than Mauser bullets.” Ironically, slate shingles had been a safety precaution mandated by city ordinances after the great fire of 1885. Now they were cutting people in half.

Through broken windows priests witnessed the tableaux of death, conscious, perhaps, that there was something almost biblical in the strength and random cruelty of the storm. A panicking horse galloped through the surging waters of Twenty-first Street on a rendezvous with death. At that exact moment the wind ripped an enormous beam from a building and launched it, end over end, as casually as an Olympian might toss a baton, killing the horse in his tracks. Above the fury the priests heard shotgunlike explosions as the iron bands and clasps that anchored the two-ton tower bell began to break free. A second tower at the front of the cathedral groaned, then its iron crosses toppled and crashed through the roof. Moments later the tower itself gave way and pitched forward into the racing brown torrent that used to be Twenty-first Street. The bishop touched Father Kirwin’s arm and told him: “Prepare these priests for death.”

A German servant girl working in the home of W. L. Moody, Jr., was sent on an errand and returned to report that the water standing in the yard tasted salty. Salty? How could that be? But Moody understood, and he ordered his servants to evacuate his wife and children to his father’s home, a block west on Twenty-third Street. The unthinkable had happened—the entire island was covered by water. The Gulf and the bay had converged, and for the time being, Galveston was no longer an island but merely part of the ocean floor, its houses and buildings protruding like toys in a bathtub.

By three-thirty, Isaac Cline had recognized the scale of the disaster and drafted a final message to the chief of the Weather Bureau in Washington, D.C., advising him that great loss of life was imminent and the need for relief was urgent. Joseph Cline waded through waist-high water to deliver the message to Western Union, only to discover that all the telegraph wires were down. He was able to get a telephone message through to the Western Union office in Houston, but no sooner had he delivered his report than the line went dead. Now Galveston was completely cut off from the outside world, alone with the fury of the gale and the rage of the tide.

Having done his duty, Isaac Cline left the bureau in the hands of assistants and waded nearly two miles to his home, thinking of his pregnant wife and three young daughters. Because of complications with the pregnancy, he had been unable to move his wife to a more secure place in the center of town. The wind wasn’t yet constant—the gusts were estimated at between 60 and 100 miles per hour—and by waiting for the lulls between gusts he was able to make headway. Cline had never seen anything like this; nobody on the Island had. Roofs were sailing through the air like discarded pages of newspaper. Timber and bricks rocketed out of nowhere, splitting the paling and weatherboarding of houses. Nothing was where it had been that morning. Homes were gone. Streets had disappeared. Waves had washed wreckage against the pilings of his own home, creating a dam and backing up water to a depth of twenty feet: Cline’s house was now in the center of a small lake.

Cline found his family and about fifty neighbors huddled together on the second floor, frightened but apparently well. Joseph, who had made one last swing along the beach, warning people to seek shelter in the city’s center, arrived a few minutes later, badly shaken. “I tried to tell them that the worst was yet to come,” Joseph yelled above the clamor. “I saw a family trying to reach the Catholic Convent, but they never made it. I saw people killed by flying debris and people drowned.” Isaac realized that they were witnessing a sort of cataclysmic chain reaction. As buildings nearest the beach were demolished, the wreckage was collected by winds and waves and driven against other buildings, which in turn collapsed and joined the grinding, swelling, insatiable mass. The storm was creating a battering ram of debris, mowing down everything in its path, scraping the earth clean. Soon it would be their turn.

The storm was intensifying with each minute. At five the anemometer at the weather station recorded a two-minute gust at 102 miles per hour. Fifteen minutes later the wind carried the instrument away. By six the tide was swelling at an incredible rate of two and a half feet an hour and the wind was shifting around to the east. At about seven-thirty, in a single enormous swell, the tide rose four feet in four seconds. The center of the hurricane apparently passed west of the Island between eight and nine p.m. By then the velocity of the wind was estimated at 120 miles per hour. The tide on the side of the Island nearest the Gulf was at least 15 feet; breakers 25 feet or higher crashed over the beachline.

Every church, hospital, building, or home still standing became a shelter for the homeless. In a frantic effort to do what they could against a force nobody could comprehend, workmen braced walls with beams and nailed doors and windows shut. Holes were drilled in floors to invite floodwater to enter, in the hope that the water would help anchor houses and keep them from floating off. From one end of the Island to the other—in their instinctive struggle to survive for even one more minute—people committed astonishing, desperate, heroic, and sometimes foolish acts.

A nurse on duty at a home near the beach wrapped the body of a stillborn infant in a blanket, administered a sleeping potion to the helpless, pain-racked mother, and then, as the house began to disintegrate, calmly made preparations for her own escape. She put on a man’s bathing suit, cut off her hair with scissors, and plunged into the sea. From eight in the evening until two in the morning she clung to a piece of driftwood, finally washing ashore on the mainland. Naked, bleeding, and shivering in the cold rain, she found a shaggy dog and snuggled up against him until daylight.

On the beach three miles west of town, the sisters of St. Mary’s Orphanage herded their 93 children from room to room as the storm worsened. Their final refuge was the second-floor girls’ dormitory. A caretaker brought a coil of clothesline from a storeroom, and the sisters wrapped ropes around their own waists and then around the children. A short time later the roof caved in, and all the nuns and all but three children were crushed or washed to their death.

When the front section of YMCA secretary Judson B. Palmer’s house on avenue P 1/2 washed away, Palmer, his family, and fourteen others crowded into an upstairs bedroom and began to pray. Palmer’s young son, Lee, prayed for the safety of his dog, Youno, and asked Jesus to “give us a pleasant day tomorrow to play.” One room after another collapsed and disappeared until all that remained was a room at the north end, part of the roof, and the bathroom. As the water continued to rise, Palmer and his wife and child climbed up on the edge of the bathtub. When the water reached their chins, the boy put his arms around his father’s neck and asked if everything was all right. Palmer never got a chance to reply. At that moment the final section of the house gave way, hurling everyone into the roiling current. For three hours Palmer drifted on a floating shed. Eventually he was rescued, but he never saw his wife or little Lee again. Of the fourteen neighbors who had taken refuge in the Palmer home, only one survived.

Far down the west end of the Island, Henry R. Decie, his wife, and baby boy took shelter in the home of a neighbor. The Decies were resting on the end of a bed, the baby between them, when the water began to rise “four or five feet in one bound.” At that same moment a wave slammed into the side of the house and took it off its blocks. “My wife threw her arms around my neck,” Decie recalled, “and kissed me and said, ‘goodby, we are gone.’ ” The house shook violently, dislodging a beam that came crashing down. Decie tried to scoop his son into his arms, but the heavy timber caught the child and killed him instantly. “Another wave came,” Decie said, “and swept the overhanging house off my head. I looked around and my wife was gone. Catching a piece of scantling, I held on to it and was carried thirty miles across the bay, landing near the mouth of Cow Bayou.”

Though the front and rear porches of Isaac Cline’s home had been smashed to sticks, the fifty refugees inside told themselves that the house was secure. Joseph Cline remembered feeling strangely calm. He kept thinking of an uncle who, alone of all those aboard a sinking ship, saved himself by hanging on to a plank and riding it five miles to shore. Around him, people were singing or praying or crying—or wandering about aimlessly, looking for some place that might give them an advantage when the end came. “I knew the house was about to collapse,” Joseph Cline said, “and I told my relatives and friends to get on top of the drift and float with it.”

The storm had been pounding against a quarter-mile-long section of streetcar trestle built out over the Gulf. Suddenly the trestle pulled loose from its mooring—rails, ties, crosspieces, and all. The storm surge and the 120-mile-per-hour winds carried a two-hundred-foot trestle section like a scythe out of hell, directly toward Isaac Cline’s home. A fraction of a second before the collision, Cline felt his house move off its foundation. Then it began to topple and break apart. Cline tried to wrap his arms around his wife and six-year-old daughter, but the impact threw them into a chimney and swept the three of them beneath the wreckage, to the bottom of the water. Cline lost sight of his daughter. A dresser pinned him up against a mantel, and his wife was trapped nearby, her clothing tangled among the wreckage. It’s over, Cline thought. Surrendering to the inevitable, he told himself: “I have done all that could have been done in this disaster, the world will know that I did my duty to the last, it is useless to fight for life. I will let the water enter my lungs and pass on.” Then he lost consciousness.

Joseph Cline had been standing near a window on the windward side. When the house began to capsize, he grabbed the hands of Isaac’s other two daughters, smashed the window glass and storm shutters with his back, and let the momentum carry the three of them through the window. The building settled on its side, rocked a bit, and then rose to the surface of the floodwater. Joseph Cline and his nieces were alone on the top side of a flotilla of wreckage, momentarily safe and drifting with the tide. Rain was driving down, and pieces of timber went by like swarms of giant insects. A dim moon shone through broken clouds, making it possible for Joseph to see a short distance. Heaving masses of debris, like the one that served as their rescue ship, stretched for blocks. Except for Joseph and the two youngsters, there wasn’t another human in sight.

In a night of catastrophic losses, it was impossible to separate coincidence from miracles, but there was an abundance of each. Isaac Cline regained consciousness to find himself hanging between two timbers: the wave action against the timbers had apparently pressed the water out of his lungs. There was a flash of lightning and Cline saw his youngest girl, alive and floating on the wreckage a few feet away. A short time later another flash revealed his brother and his other two daughters, still riding their raft of debris. “I took my baby and swam toward them,” Isaac recalled. “Strange as it may seem these children displayed no sign of fear, and we in the shadow of death did not realize what fear meant. Our only thought was how to win in this disaster.”

For four hours they drifted through endless darkness and despair. Over the downpour and the wail of wind, they heard houses being crushed and the screams of the dying. Isaac and Joseph Cline turned their backs to the wind, placing the children in front to protect them from flying debris. Periodic flashes of lightning added to the surreal specter and revealed the terrible carnage—and sometimes the approach of new danger. At one point they saw a weather-battered hulk that had once been a house streaming in their direction, one side upreared at a 45 degree angle. The hulk towered six or eight feet above them and was bearing down like a derelict freighter, crushing everything in its path. Joseph Cline retained sufficient presence of mind to leap just as the monster reached them, gaining a grip on the hulk’s top edge. His weight was enough to drag it lower in the water, and with his brother’s help, they pulled the upper side down. They climbed on top with the children, just as the drift upon which they had been floating went to pieces under their feet.

For a time their new makeshift raft was swept out to sea, but then the wind became southerly, indicating that the storm was turning inland. Gradually they could again see the lights of shore. They were drifting toward a steady point of light and as they got closer they realized that it was a house on solid ground. Battered and exhausted, they climbed through an upstairs window of the house, which was on the corner of Twenty-eighth and Avenue P—five blocks from where Isaac Cline’s home had once stood. Their journey through hell had delivered them close to the place where they had started.

August Rollfing was frantic. At the peak of the storm he had stood on the counter of a store with eighty strangers, holding a small boy he had never seen before on his shoulders and praying that his own family had somehow survived. When the water began to recede, Rollfing ran toward the west end neighborhood where his mother lived. He was relieved to see her house still standing—it was the only one on the block that was—but when he got inside and asked about Louisa and his children, his mother just shook her head. “They are not here, my boy,” she said. “I haven’t seen them.” She begged him to wait until daylight, but he bolted out the door and disappeared into the rain.

His throat dry and his chest burning, August raced along Twenty-third Street in the direction of Broadway, thinking that his family might have taken shelter at his sister Julia’s house. A faint moon broke through the clouds, and August saw some sort of gigantic shadow stretching across Avenue N, blocking his path. It looked like a levee or a small mountain range, and it stretched from east to west, as far as he could see. August was nearly to the base of the shadow when he realized that what he was looking at was a monstrous wall of wreckage. It was taller than a two-story building and four to ten feet wide. It started at the Flats on the far east end of the Island and ran all the way to Forty-fifth Street. In its relentless, grinding fashion, the battering ram that Isaac Cline described had rumbled across 1,500 acres, finally playing itself out against a breakwater of its own creation.

August Rollfing stood looking up at this grotesque monument to death, trying to comprehend. “It seemed endless,” he remembered. “House upon house, all broken to pieces, furniture, sewing machines, pianos, cats, dogs . . . and what was underneath? How many people had gone down with their houses? And behind the wall of debris, nothing! Absolutely nothing! The ground was as clear as if it had been swept, not even a little stick of wood. For blocks and blocks, nothing, and then that terrible pile of debris . . . and what was in and under it.”

By the time August Rollfing reached his sister’s home, the rain had almost stopped and a fresh breeze was whipping straight out of the south. In a few hours it would be light. Julia’s home was still standing, more or less. There was a twenty-foot hole in one wall where the kitchen had broken loose, and the house had been lifted off its brick pillars on two sides so that it leaned drunkenly, like a house in a child’s drawing. When August saw that his wife and children were safe, he collapsed in a heap on the stairway.

Sunday morning was a scene out of hell, played against a brilliant blue sky and a drowsy sea. At low tide, the Gulf seemed as peaceful as a sleeping teenager, spent and unaware of its night of murderous violence. Small groups of people began to appear in the streets, tentatively at first, as though they didn’t want to disturb anything. Wet and chilled to the bone, bruised and stunned, they stumbled about, trying to assimilate the scope of this tragedy.

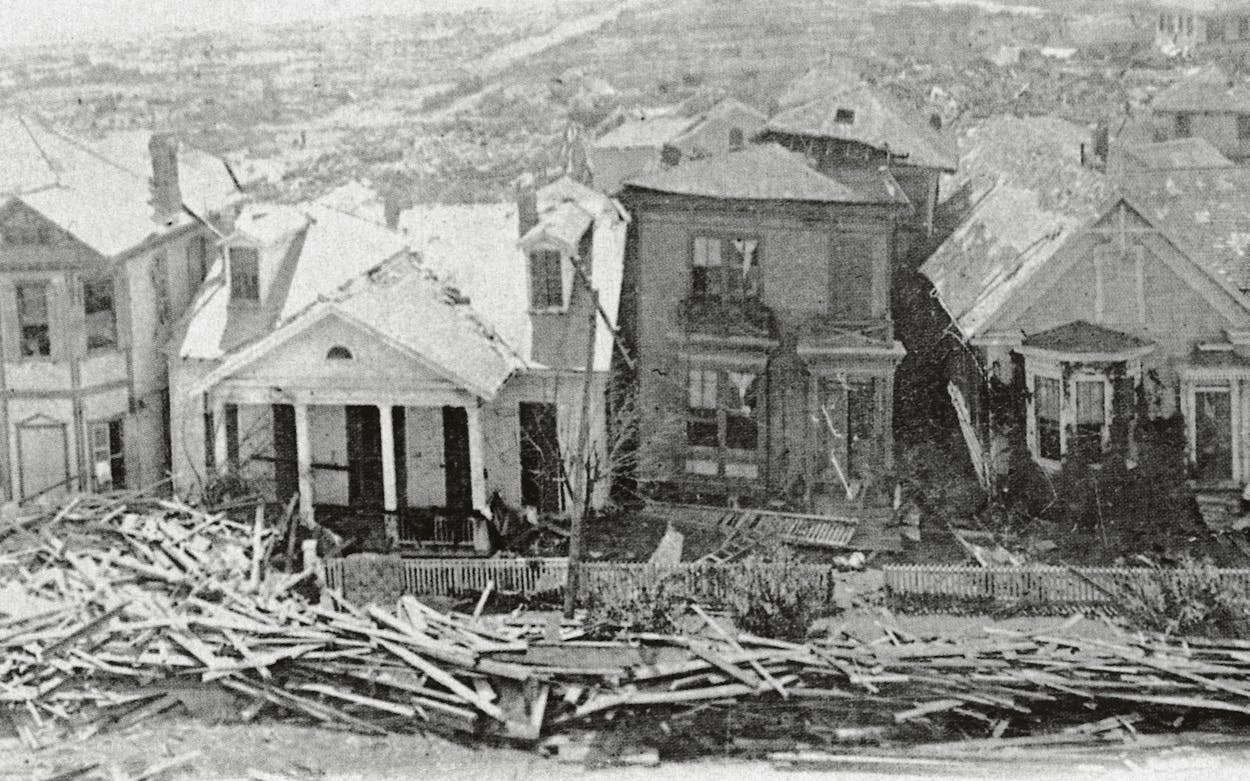

Those who had stoves and chimneys standing did what they could to cook breakfast. Others looked for dry wood. The entire Island was waterlogged and covered with an inch-thick layer of foul-smelling slime. Still others dared to survey the damage. It was worse than anyone had imagined, far worse. In their blackest hour, not one of them had conjured up a vision as horrible as what was spread before them this Sunday morning. One third of the Island was scraped clean, and the other two thirds was battered almost beyond recognition. In the Sunday morning stillness, people climbed on top of the debris and looked around. They heard faint cries from people buried alive. At first their impulse was to attempt rescues, digging with their bare hands or whatever tool they could find, but it was hopeless: No human effort could alter the inevitable or limit the final suffering of those who were trapped and waiting to die.

A more urgent concern was aiding the injured and homeless. There wasn’t a house or building on the Island that had escaped damage. More than 3,600 houses were totally destroyed, as were hundreds of buildings. Sacred Heart Catholic Church was in ruins. St. Mary’s Cathedral was nearly in ruins, but miraculously one tower remained, where Mary, Star of the Sea, continued to stand watch. The fourth floor of the Moody Building was gone, sheared away as though by a giant knife. The east wall of the opera house had collapsed, and the interior was coated with slime the consistency of axle grease. Except for a few scattered bricks, there was no trace of St. Mary’s Orphanage. Railroad tracks were twisted and broken, trees uprooted, telephone poles flattened, wires ripped loose. Huge oceangoing ships had torn free from their ropes and cables and had been swept across the bay and deposited on the mainland. The British steamship Taunton was carried from its anchorage at the mouth of the ship channel to a thirty-foot bank at Cedar Point, 22 miles from deep water. Household items, clothing, trade goods, machinery, almost every material possession that wasn’t stored higher than fifteen feet, was saturated with salt water and scum. Weeks and even months later, bicycles that seemed no worse for the experience suddenly fell apart, rusted from the inside.

There were so many bodies that after a while the senses numbed and the corpses seemed to be merely some sort of demented design. They were heaped together in the streets, strewn across vacant lots, sticking from mounds of wreckage, floating in shallow pools of water, scattered along the beach, bobbing in the filthy backwashes of the bay. Most were naked, mutilated, and dashed beyond recognition. They hung like macabre ornaments from trees, trestles, and telephone poles. One observer counted 48 bodies dangling from the framework of a partially demolished railroad bridge. The horror and the unspeakable suffering of the victims’ final moments were often preserved in ghastly frescoes of death. The body of twelve-year-old Scott McCloskey, the son of a sea captain, was found with his left arm shattered, his right arm still wrapped protectively around the body of his younger brother. A woman, her long blond hair entangled in barbed wire, reached back in death as though to disengage it. Miles down the beach from the orphans’ home, the bodies of a nun and nine children, still tied together with clothesline, lay half buried in sand and seaweed.

For days survivors continued to search among the ruins, hoping to find some trace of loved ones. Most of the dead were so badly battered they couldn’t be identified. Father Kirwin, who had waited out the storm in St. Mary’s Cathedral, told of seeing a man going from corpse to corpse, looking into their mouths, hoping to recognize his wife’s bridgework. Twenty days after the storm, Isaac Cline found the body of his wife, under the wreckage that had carried the rest of her family to safety. He knew it was she because of her diamond engagement ring.

All day Monday and Tuesday, carts and wagons full of corpses plodded along the ravaged streets toward the wharves, arms and legs protruding from under tarpaulins. The Central Relief Committee had decided that it had no choice but to dump the bodies in the Gulf. Every adult male on the Island was pressed into service, but the job of loading the bodies onto barges and taking them to sea was so abhorrent that recruits had to be rounded up at bayonet point and plied with whiskey. “An armed guard brought fifty negroes to the barges and went on with them,” Father Kirwin recalled. “The barges were taken out into the Gulf and remained there all night, until it was light enough for the negroes to fasten the weights and throw the bodies overboard. When the barges returned those negroes were ashen in color.”

Two days later the bodies began to wash up on the beach. Since it was no longer possible to lift the decaying bodies onto carts and haul them through the streets, the relief committee decided to burn the corpses on the spot, along with the mountain of debris. From one end of the Island to the other, funeral pyres burned night and day. No one alive ever forgot the sight, or the smell.

Nor could anyone know for certain how many Islanders died that weekend in September. The number has been estimated between 6,000 and 8,000. Altogether, the hurricane claimed 12,000 lives on the Island and the mainland. The storm was recorded as the worst disaster in the history of the United States. An article a month later in National Geographic described Galveston as “a scene of suffering and devastation hardly paralleled in the history of the world.”

One reason the death count was so inexact was the massive migration that followed the storm. In the immediate aftermath, people were paying huge sums for boat passage to the mainland. Once rail service was restored, railroads gave victims free transportation anywhere in the United States, and hundreds of families took advantage of it. Many never returned. So great was their suffering and grief—so terrible the memory of that night—that they didn’t even bother to go back for their possessions or to look for or bury their dead.

While most of Galveston’s leading citizens were meeting that tragic Sunday morning to form a relief committee, W. L. Moody, Jr., had his own agenda. His father, the Colonel, was in New York on business; it was company policy that Will Junior and his father couldn’t both be off the Island at the same time. At first light the dutiful son took a crew downtown to clean up the debris so that the Moody bank could open on schedule on Monday morning.

When Will Moody, Jr., told the Colonel that people were leaving the Island and that business was bound to suffer, the Colonel uttered one of the best known and most cynical remarks in Galveston lore. “Good,” he declared. “Remember, we both love to hunt and fish. The fewer people on the Island, the better the hunting and fishing will be for us.”

The Colonel was speaking metaphorically. The Island would recover—there was no doubt about that—and in the meantime it was a buyer’s market. Property values dropped drastically. Indeed, prospects for hunting and fishing hadn’t been this good since Samuel May Williams and the other founders of the original Galveston City Company began dividing up the Island in 1838. The Colonel returned from New York convinced that the Eastern press had greatly exaggerated the damage done by the storm—he’d even brought a stack of newspapers to show his son—but when he saw with his own eyes that the devastation was even worse than reported, he made his plans accordingly. Two weeks after the hurricane, Will Moody, Jr., purchased a thirty-room mansion at 2618 Broadway for ten cents on the dollar.

From The Island: A Narrative History of Galveston, by Gary Cartwright, to be published next spring by Atheneum.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Galveston