As Texas Alexander walked down the dusty dirt street in his hometown of Richards, Texas, in early 1954, his intense pain only allowed a few steps at a time. He was covered in sores. Ill, impoverished, and shunned for a double murder that likely never happened, Alexander would soon die of syphilis and be buried in an unmarked grave at Longstreet Cemetery, just outside the East Texas town. There was no headstone to commemorate his legacy as one of the nation’s greatest early blues singers.

Today only hard-core blues fans and fellow musicians remember Alexander’s name, in part because his recording career was brief and his early death came before the blues revival of the 1960s. But his talent was undeniable, and he left a lasting mark on dozens of legendary artists, from Lightnin’ Hopkins to legendary blues guitarist Lowell Fulson. Alexander was “one of the major singers of Texas, and indeed of the blues as a whole,” blues historian Paul Oliver wrote, “one whose work, more than that of any other blues singer, was rooted in the vocal traditions of the plantation and the penitentiary.” Fulson, who got his start in music by touring with Alexander, was another of the few who never forgot him. “When he sang you could hear him a block away,” Fulson later recalled. “He really had that big voice. He had a big chest and he didn’t sing, he just roared. . . . He filled every place he went in.”

Alger or Algernon (his true first name is unknown) was born in the Central Texas town of Jewett on September 12, 1900, to Sam Alexander and Jennie Brooks. The boy’s family called him Algie. Two years later, a brother named Edell was born.

At some early point in Alexander’s life, his mother abandoned the family, leaving the kids with their aunt Alice. “His mama was rowdy, she was runnin’ about,” said Mattie Richardson, a neighbor. “She didn’t have time to take care of two children.” Sometime after her departure, law enforcement reported her death to the family. Neither Alice nor the boys’ father seemed to be very interested in raising the children, and at some point Alice left the brothers with their grandmother in Richards, Texas. Alexander’s lyrics would later reflect his hard feelings toward his mother and his disillusionment with women in general. In “Death Bed Blues,” he wrote, “Mama’s dead, mama’s dead, papa’s gone astray / She left me in this world, nothing but a slave.”

According to the 1940 census, Alexander’s schooling ended after the third grade. He grew up picking cotton and possibly working in the sawmills in the area. Alexander was short—about five feet tall, according to contemporaries—but his forearms were “like iron,” Fulson said. It was in the fields that the young Alexander learned the original blues. Cotton picking is back-breaking work, and to pass the time, Black Americans made call-and-response music, a combination of rhythms mixed with spirituals and chants. Whereas other early blues stars like Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lead Belly found fame with blues blended with folk songs, Alexander’s style of “primitive blues” came straight from the cotton fields. His music was sorrowful and uplifting at the same time. As Paul Oliver wrote in 1991, “He might well be said to have been the quintessential blues [singer] for all but one of his sixty-six issued titles . . . were blues of the most rural kind.”

Alexander’s friends called him Texas because he wore a big cowboy hat. “I don’t know if he’d be five foot or not. He was a low guy like that,” recalled James Menefee, an acquaintance from Richards. “He’d be wearing a big hat always.” Fulson later remembered Alexander as uncommunicative, until he sang—then he became glib and confident and came alive. With his voice as his only instrument, Alexander started entertaining at picnics. He would hum the tune and tell the accompanist, “You don’t play with me, you play after me.” In 1964, Lightnin’ Hopkins recalled one of those picnic performances held during a baseball game in Normangee, Texas: “He just like to broke up the ball game. Peoples was paying so much attention to him.”

By the late 1920s, Alexander had left the cotton fields and made his way to Deep Ellum, in Dallas, where he worked in a warehouse and busked at night along the Houston and Texas Central railroad track. The area was bustling with excitement as a hub of activity for jazz and the blues. Black theater owners had formed a booking association that functioned as a vaudeville circuit for Black entertainers, and Alexander appeared in at least one of the theaters and began to make his name singing. Then Sammy Price, a boogie-woogie pianist who had gotten Blind Lemon Jefferson a record deal, heard Alexander sing and introduced him to local record-store owner R. T. Ashford. Ashford negotiated a contract for Alexander with OKeh Records.

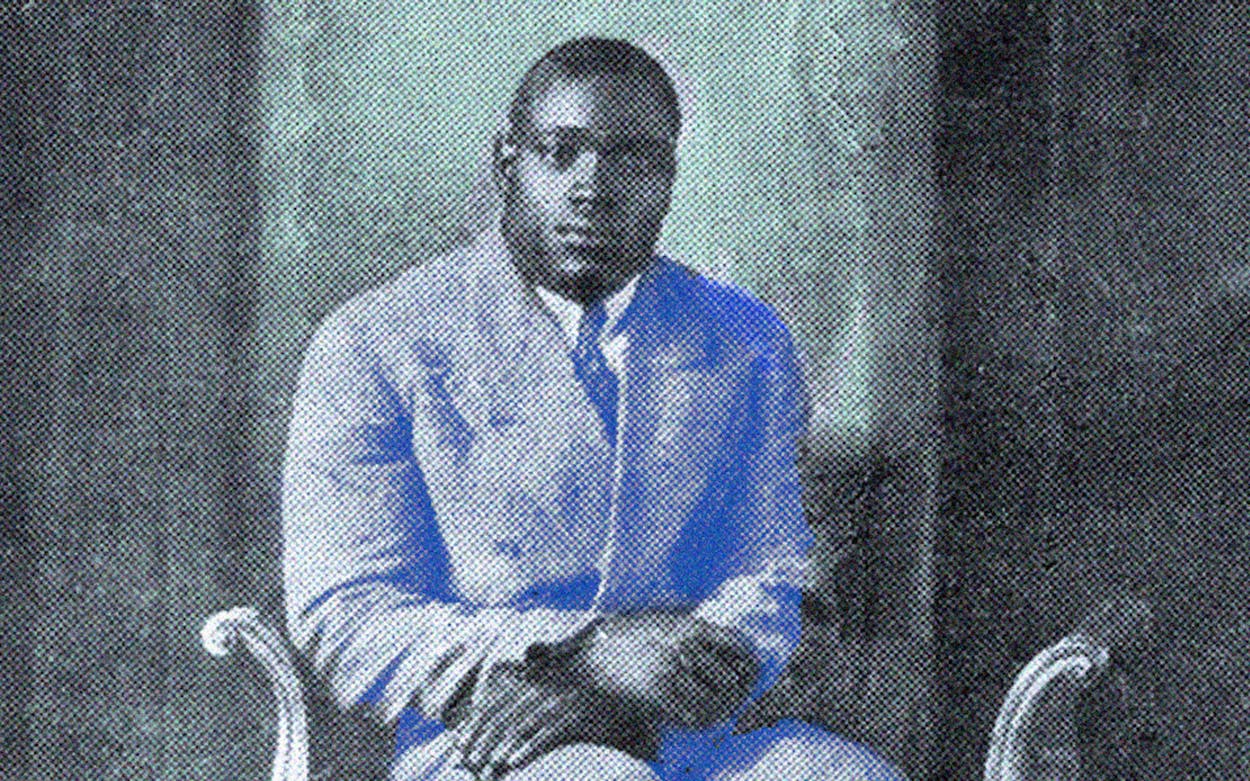

On August 11, 1927, Alexander cut his first record, “Range in My Kitchen Blues.” A picture taken to promote Alexander depicts him as a stout, muscular young man holding a cigar and sitting sideways in a chair. It is the only known photograph of him in existence.

Alexander made the record with Lonnie Johnson, a brilliant jazz guitarist, and it was a hit. More songs followed, with first-class musicians—the great Eddie Lang (Bing Crosby’s favorite guitarist), King Oliver, and Eddie Heywood. Alexander’s collaborators noted his unusual timing: “He was a very difficult singer to accompany; he was liable to jump a bar, or five bars, or anything,” Johnson told Paul Oliver. “When you been out there with him you done nine days work in one!”

Johnson’s guitar fills and Alexander’s moans and cries, with lyrics full of sexual innuendo, were hits. In “Range in My Kitchen Blues,” he sang: “I’ve got a brand-new skillet, gonna get me a brand-new lid / Gonna get me a New York woman, for to burn my Southern bread.” These recordings would become some of the finest examples of early blues ever recorded. Alexander was so well thought of by OKeh that the company had him record eight sides with its top-selling string band, the Mississippi Sheiks. (One of the Sheiks’ own records, “Sitting on Top of the World,” was a huge hit and today sits in the Grammy Hall of Fame.) On June 9, 1930, with the Sheiks, Alexander recorded what many consider to be his finest song, “Frost Texas Tornado Blues”—a documentation of the disastrous tornado of May 6, 1930, that destroyed much of the Texas town of Frost and killed at least 22 people. It seems obvious that Alexander had visited the tornado-ravaged town. His vocals were a heart-wrenching funeral dirge.

The Great Depression hit the nation hard, including the recording industry, and OKeh Records released Alexander. He started busking around Crockett and Palestine and up and down West Dallas Street in Houston, traveling in the long Cadillac he’d bought with his OKeh royalties. Many came just to see his car, a rarity in the small freedmen’s colonies he was visiting. Blues musician Sam Hopkins, later known as Lightnin’, accompanied Alexander on some of his busking trips during the early 1930s, as did Thomas Shaw, Billy Bizor, and J. T. Smith, the original Howling Wolf. Alexander taught Lightnin’ how to sing the blues, and for this, Sam Hopkins was forever grateful.

In 1934 Alexander signed a contract with Vocalion Records; he recorded fourteen sides, including “Polo Blues,” a superb song. By 1935, however, Alexander’s recording career was basically over—the blues were no longer selling due to the Depression. He toured with Lightnin’ Hopkins, and they busked from Centerville to Normangee, Jewett up to Deep Ellum, and back down to Houston. “He was a man to get up and go,” Hopkins recalled.

It was during this period that Alexander apparently helped promote a story—likely fictional—that would end up haunting him and overshadowing his musical legacy for decades after his death. The story was that he had murdered his wife and her lover, and Lowell Fulson, Frankie Lee Sims, and Buster Pickens all spread it. Alexander apparently related the tale of murder to Fulson, perhaps as they were driving on the dark roads in Texas. “He was sent to penitentiary for killing his wife and her boyfriend. He had beheaded them with a hatchet,” Fulson recalled. Frankie Lee Sims, an early R&B star who claimed to be Alexander’s nephew, said Alexander served time in prison for the crime. But a thorough search of Texas prison records and various county records finds no evidence Alexander was ever tried for murder or served time for a killing. None of Alexander’s close relatives seemed to have heard the murder story, either. “I really can’t believe it,” his cousin Cedell Johnson later recalled. “If he had been to the pen for killin’, his auntie and his grandmother woulda knowed something about it.”

If Alexander created the tale, he might have been inspired by Lead Belly, who had served time for murder and enjoyed a certain notoriety. Alexander’s death certificate lists him as widowed, but no census records or county licenses provide evidence of a marriage. When it comes to Alexander’s personal life, there are more questions than answers.

While Alexander apparently never went to a state prison, he probably did serve time on a county work farm, according to several of his contemporaries, for singing “hokum” songs, like “Boe Hog Blues,” which were full of sexual innuendo. He was once severely beaten for singing a hokum song in public. Contemporaries remembered seeing Alexander here and there during the 1940s, working at a service station in Dallas and busking in Deep Ellum. Then he turned up in Houston living with his brother, Edell. For the 1940 census, he didn’t even mention he was a singer and artist, instead giving his occupation as “cotton picker.” Marcellus Thomas, a blues guitarist from Oklahoma, heard him singing “Tom Moore’s Farm” (also known as “Tom Moore Blues”) in Dallas in 1942. Alexander would teach the song to Hopkins, and it would make Lightnin’ famous.

In 1946, Alexander got one last shot at renewing his stardom. Lola Anne Cullum, a dentist’s wife in Houston who had discovered the jump-blues pianist Amos Milburn, fancied herself a talent agent for Aladdin Records, of Los Angeles. Cullum was driving Lightnin’ Hopkins to California to record, and Alexander pleaded to go along. Cullum passed, later explaining that she was frightened of Alexander, as she had heard he’d just gotten out of the penitentiary.

Alexander continued to busk, but the ravages of syphilis were killing him. In about 1950, he was asked to make a record by Saul Kahl, a Houston doughnut shop owner who owned a local label called Freedom. Alexander cut two songs with blues guitarist Leon Benton and pianist Buster Pickens. The recording is raw, and Alexander’s vocals are weak from his disease, but the record has become a prized collectors’ item: one side was possibly the first recorded cover version of Robert Johnson’s classic “Cross Road Blues.”

Edell died in 1950, and Alexander moved back to Richards. When he died a pauper on April 16, 1954, at age 53, there was no obituary for the man who did so much for the blues. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Montgomery County. Finally, in the mid-2010s, the Killer Blues Headstone Project, a Michigan nonprofit that places markers for forgotten blues musicians, added a headstone. Above the name “Alger ‘Texas’ Alexander” were two simple words: “Blues Legend.”

Coy Prather is a music historian who published the book A Tombstone for Texas: Texas Alexander and the Blues Pioneers of Texas in spring 2023.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Blues