On the side of every Whataburger cup is a phrase that sounds like it belongs on an emo teen’s Tumblr: “WHEN I AM EMPTY DISPOSE OF ME PROPERLY.” There are no further instructions.

Unless, that is, you’re the inquisitive type who looks at the undercarriage of your medium Diet Coke or limited-edition Peaches & Cream milkshake and observes that the bottom of the cup is printed with a recycling symbol surrounding the numeral six. The six refers to the cup’s material, which is a hydrocarbon-derived polymer known as polystyrene. (Polystyrene is commonly referred to as Styrofoam, a trademarked brand.) More specifically, the cups that keep your milkshake from melting between Whataburger’s drive-through window and your house are made from expanded polystyrene—basically, millions of tiny plastic bubbles.

In terms of cheap insulation, almost nothing is as effective as expanded polystyrene. As Jaime Grunlan, a mechanical engineering professor at Texas A&M University, explained to me, polystyrene has bad thermal conductivity (meaning it doesn’t transfer heat well), and air has “horrible” thermal conductivity. The pairing of the two in cup form is what keeps your coffee from burning blisters on your palm; the material also keeps cold drinks cold for a long time, even in Texas heat. For these reasons, and because it’s extraordinarily cheap to produce, the stuff is a fast-food purveyor’s dream.

The downside: polystyrene is very difficult to dispose of in an environmentally friendly manner. Number-six recycling products must be processed at special plants, which don’t exist in many communities around the country, including most cities around Texas. When I looked up where to take a cup in San Marcos, where I live, the city-designated specialty recycling plant’s website directed me to the nearest landfill in New Braunfels, a 25-minute drive away. If I wanted to make the drive up I-35 to Austin, I could haul my cup out to a special recycling plant near the airport. Or, if I felt extraordinarily enterprising and waited until I made a trip home to Houston, I could go to one of two recycling centers located between the Loop and the Beltway.

According to Luke Metzger, who helms Austin-based advocacy nonprofit Environment Texas, throwing the cups in the recycling bin at home may do more harm than good. “Residential recycling streams aren’t set out to handle polystyrene,” Metzger told me. “As a result, if it gets crushed in with other recyclables, it can basically contaminate an entire truckful of recyclables.”

Metzger is well versed in the dangers polystyrene poses to the environment. He and his friend Neil McQueen, an environmental consultant in Corpus Christi, have been trying to chase expanded polystyrene out of Texas, one business at a time, for years.

If the cups are placed in a garbage can, Metzger said, they’ll end up in landfills, where they may take upward of five hundred years to break down. And they never fully biodegrade. If Cabeza de Vaca had stopped for gas at a Stripes on his cruise over to the Gulf and thrown his cup under a shade tree in Galveston, the cup might very well still be there, or more likely in a museum somewhere, as the first piece of litter thrown by a European upon this strange and beautiful land.

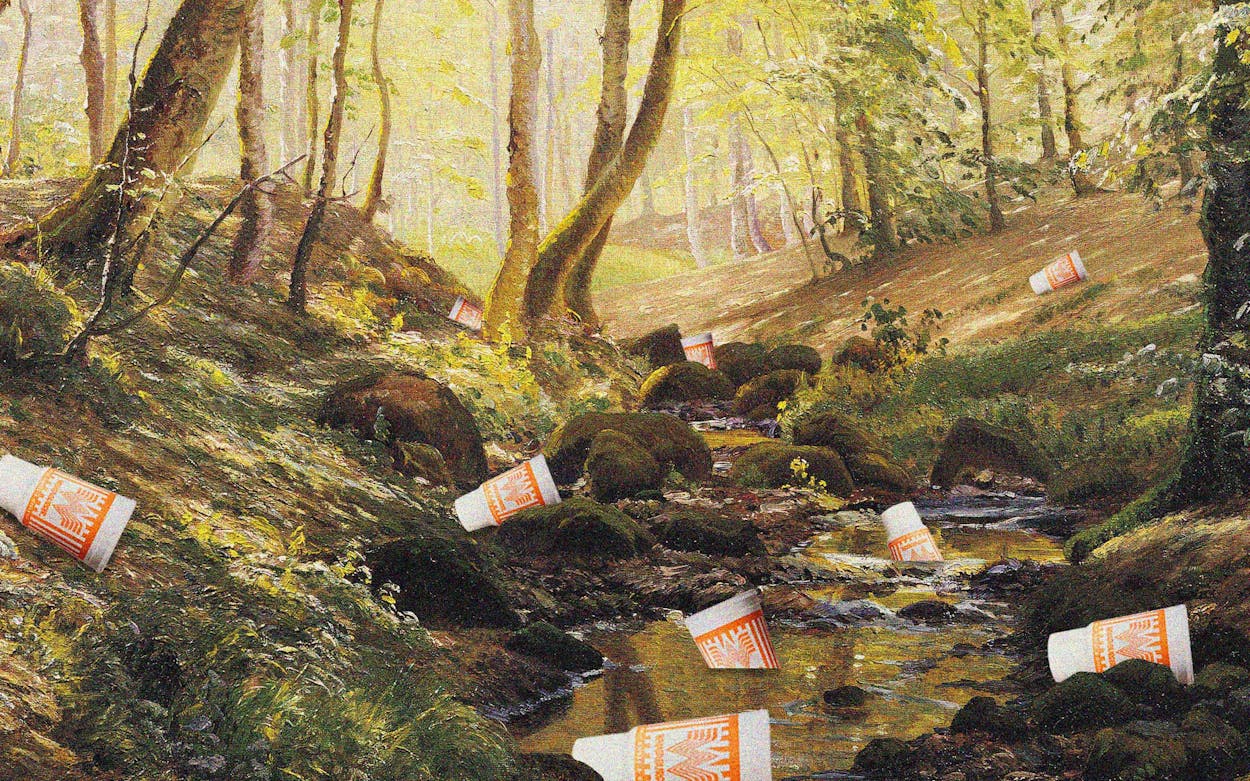

A cup tossed out in the sunlight—say, alongside a highway—might melt over a period of years. But it might also wash away in one of the state’s frequent floods, winding up somewhere like Corpus Christi Bay. A video McQueen pointed me to on YouTube, “All the Cups,” shows dozens of foam vessels drifting into the bay after a rainstorm in Corpus. About half of them are the unmistakable orange- and white-striped variety handed out by Whataburger.

Once the cups are in the water, McQueen told me, the rocking motion of the waves and UV rays from the sun can break them down into infinitesimally small pieces, which marine animals may mistake for food, filling up their bellies with plastic instead of nutrients (the long-term effects of fish ingesting microplastics are still being researched). Cups in various stages of degradation sometimes wash ashore, where McQueen and his neighbors are forced to look at them every day. “What you end up with on our shorelines are pieces of cups,” he told me. “Little tiny polystyrene pieces everywhere.”

And yet folks can’t get enough of the cups, especially the ones they associate with beloved, San Antonio–based Whataburger. One kid from Houston, Foster Mohning, has kept more than 150 of them as mementos of fun times, according to a story on the Whataburger news site. And the Whatastore—Whataburger’s purveyor of merch—sells, for $45.99, a keepsake YETI tumbler (currently out of stock) that is identical to the restaurant’s disposable cups but is, happily, reusable. Once, at a Texas-themed party I attended in Brooklyn, a friend who was manning the deejay booth had brought a foam Whataburger cup with him all the way from San Antonio as a prop. The cup could be seen throughout the night bobbing and bouncing above the crowd, radiant and prominent as a disco ball.

McQueen won’t go to Whataburger anymore—he’s too turned off by their material choices—but Metzger loves the place. “If there’s a Whataburger versus In-N-Out situation, I’m firmly in the Whataburger camp,” he told me. “I just wish they would hold the polystyrene.” He doesn’t think any cup, even one from a revered Lone Star brand like Whataburger, should pollute the state for centuries. But a vocal group of Texans begs to differ: Those dang cups keep their ice pellets frozen and milkshakes frosty on the most hellish of summer afternoons, and isn’t that a miracle worth preserving?

Metzger and the Whataburger cups used to have this thing going. Starting in 2018, he’d spot one rolling down a concrete gutter, or tangled up in the shade of some tall grass, take a picture of it, and tweet it at Whataburger. The idea to take on the Texas behemoth came from Environment Texas’s dues-paying members, who, amid the sweet high of a victory against the foam cups of Austin sandwich chain ThunderCloud Subs, were eager to tackle a bigger boss.

In summer of 2018 the Texas Supreme Court had made it clear that trying to get individual municipalities to ban polystyrene containers was an absolute no-go. In City of Laredo v. Laredo Merchants Association, the court unanimously ruled that a section of the Texas Health and Safety Code makes it illegal for any local government to ban the use of specific containers or packages (the decision made plastic bag bans, like the ones in Austin and Laredo, illegal as well). Change would come not from the state, but from businesses.

To Environment Texas, Whataburger felt like an obvious target: with more than seven hundred restaurants in Texas alone, and what with the cups holding a prominent place in the canon of Texas iconography, getting Whataburger to trade in the polystyrene foam for a friendlier alternative, such as compostable paper, wouldn’t be just an environmental victory, but a symbolic one. Whataburger, the activists thought, was big enough and beloved enough to be a catalyst for statewide environmental progress.

And Whataburger would not be the first large chain to choose to move away from polystyrene. Early in 2018, McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts had pledged to eliminate polystyrene cups from all stores. In June 2018 Whataburger even released a statement about its cups to news outlets: “We’re continuously researching new products and we’re currently looking at cup alternatives that keep drinks at the right temperature,” the statement said. “Our Styrofoam cups are recyclable and we encourage everyone to dispose of them properly.”

Environment Texas launched a multipronged effort that it called, in one of many riffs on Whataburger’s name, WhataWaste. As Metzger told me over the phone, his first act was to ask Whataburger, in a letter, to consider switching cup materials. That letter, he said, was met with silence. Then there was a series of pickets, in which Metzger and his cohort stood outside Whataburger locations with signs reading “What a Waste.”

Metzger and McQueen kept up their efforts. Along with the Twitter campaign, there was a formal letter, signed by a slew of other environmentally minded folks, including Christine Figgener, a Texas A&M marine biology PhD candidate who had recently gone viral for pulling a straw out of a turtle’s nose on video. And then, finally, they launched a petition.

“Whataburger, stop using polystyrene foam cups!” the petition demanded. Metzger and his team canvassed door-to-door with the petition and circulated it online. Thousands of environmentally conscious Whataburger consumers flocked to it. By November 2018, the petition had gathered more than 53,000 signatures (now it has more than 102,000). On November 19, Metzger and McQueen delivered copies of the letter and petition to various Whataburger branches around the state, and finally got the company’s attention. Executives agreed to set a meeting for December, at a municipal building in San Antonio.

The day of the meeting, Metzger and McQueen brought with them two garbage bags full of cups that McQueen told me he’d collected from around the bay in Corpus in “an hour, tops.” They set the bag on the floor behind them and pleaded their case to Whataburger: trading polystyrene cups for a more sustainable option would do a world of good for future generations of Texans. McQueen and Metzger recalled the reps nodding along and promising to look into it. The meeting ended, and they emerged onto the San Antonio sidewalk with their cups, feeling less than optimistic.

Months later, Whataburger sold to a Chicago-based investment firm, to the understandable lament of Texans. Metzger and McQueen have not heard from the company since their meeting. Eventually, the follow-up emails Metzger sent started bouncing back. His efforts came to a complete halt when the COVID-19 pandemic started. Now, he’s waiting for the right time to pick up the fight again.

Metzger’s petition got attention not just from Whataburger but also from many of the company’s fans, who were none too pleased to see a bunch of hippie environmentalists from Austin taking aim at their beloved foam cups. Beyond a trickle of responses on social media, a smattering of counterpetitions bubbled up on Change.org, the last stop of democracy. “Keep styrofoam cups in Whataburger”—the most popular of the petitions, with 263 signatures—explains that its sponsors oppose efforts to “stop using the amazing Styrofoam cups us Texans love getting at Whataburger.”

“This is a petition for Whataburger to ignore the crazies and keep doing what they are doing,” the petition opines. “Those gorgeous orange and white cups keep us drinking out of the same cold drink all the way home. My ice doesn’t melt because it enjoys hanging around in its Styrofoam, keeping that amazing Dr. Pepper the perfect temperature.”

The signees contribute their own quips and memories of cups past. “I like my drinks cold,” is a common sentiment. So are screeds against the condensation that forms on the sides of plastic cups and can drip into the laps of one’s jeans, creating a look that can easily be misinterpreted. There are many cries of “don’t California my Texas”—unoriginal, but applicable in this case, given that dozens of California jurisdictions actually have banned expanded polystyrene.

The naysayers have a point. Several, even. The cups do keep drinks cold, even on the hottest August afternoons. You can set them down on your granny’s antiques without threat of a water ring. And there’s just something about a Whataburger cup. At that Texas-themed party I attended in Brooklyn, the deejay’s cup prop was a crowd pleaser; it gave me a gut punch of nostalgia. The cups were mainstays at high school and college parties, where they were vessels for much more than just large sweet teas. You can picture the routine: a stop at the drive-through window, a dumping-out in a nearby parking lot, a replacement illicit beverage that stayed cold well past curfew. It’s not so much that we all loved the cups; we just loved that they were always there during the good times.

I recently spent an afternoon at my local outpost, the Whataburger over at the intersection of I-35 and Texas Highway 123 in San Marcos. In one hour of sitting in my plastic booth sipping an iced tea, I saw thirty beverage cups change hands. Whataburger officials did not respond to my (almost daily) emails, calls, and Twitter messages requesting an interview, but through haphazard calculations I arrived at a very inexact estimate for the number of cups the chain might hand out nationwide in a day. And that didn’t even include the cups handed out at the drive-through, both lanes of which were bustling each time I went to sit in my booth.

Looking around the restaurant, I felt a fraction of the curse that follows Metzger as he navigates a state littered with foam confetti. I thought of how the cups look when they’re crushed in a gutter in the neighborhood of beautiful historic homes where I live, or when they’re floating like tiny buoys on the shoreline at Corpus Christi. I thought about how they’ll all age better than I will. My bones, which will, thankfully, disintegrate about a century after my death, will likely be wiped from this earth long before my iced tea cup finally decomposes.

I took my cup home, where it now sits waiting implacably on my desk. I’m still trying to figure out how to properly dispose of it.