“The World Championship Barbecue Goat Cook-off” is a wonderful string of words—twelve luxurious syllables that would feel cramped were they not so evenly arranged. Say them slowly and feel how they naturally group themselves into place. The world. Championship. Barbecue. Goat. Cook. Off. Even sped up—worldchampionshipbarbecuegoatcookoff—and pronounced with an exaggerated twang, the words flow off the tongue like Dr Pepper from the soda fountain of a Central Texas Sonic. It is music to my ears.

I doubt anyone but me has so romanticized the name of this annual festival, which has taken place in Brady, the city closest to the geographical center of the state, every Labor Day weekend since 1974. (To be clear, the goat served at the cook-off is not technically a true South Texas cabrito—a.k.a. “the veal of the goat world”—but everybody uses “cabrito” in Brady, so I will too.) But the World Championship Barbecue Goat Cook-off holds a very special place in my heart. I was more or less raised there. Or, at least, I spent the first ten or so Labor Day weekends of my life there, inhaling wood smoke, avoiding my brother’s rubber band gun, and allowing myself to be picked up and prodded by various relatives and family friends, most of whom fell somewhere on the spectrum between tipsy and blind drunk.

I saw plenty of similarly inebriated festivalgoers in the crowd this past Labor Day weekend, when I attended the forty-eighth annual event. This year, 206 cooks entered the competition, and all (or at least those still standing) had congregated in the center of Richards Park to see the winners announced. Attendees dragged folding chairs from camping sites all over the grounds, and you could tell the cooking teams by the matching custom clothing they were wearing. There was a group in bright orange T-shirts with “Los Dos Cabritos Brady, Texas” on the front. “Goat Willies Cooking Team” had driven in from Brownwood. Next to a trash can overflowing with empty Miller Lites and Lone Stars was the “Dad Bod BBQ” team, who would walk away with the number eight spot in the goat competition (there are also awards for everything from Bloody Marys to “mystery meat”). Glass bottles haven’t been allowed in the park for years, so people held koozie-covered cans, large knockoff Yeti Ramblers, and plastic mugs from the Pecos Pete’s Natural Tea + Soda booth, which cost a minimum of $15 but came with unlimited refills all day long.

Despite the lack of glass bottles and the prevalence of iPhones, the scene was nearly identical to those I had witnessed in childhood. There seemed to be as many happy children as there were tipsy adults, and all of them were desperately trying to cool off, fanning themselves with loose-leaf paper, pieces of cardboard boxes, or the heart-shaped “Kiss My Cabrito” fans that had been created for the event. The air was tinged with a scent familiar to anyone who has ever visited a proper Texas barbecue, goat or otherwise. And just as it had been back in the day, my belly was full of juicy goat, after I gorged myself on a shank cooked by a local man everybody calls Piggy.

The biggest difference between now and then, though, was that I didn’t know anybody. None of the family and friends from back in the day were competing or judging this year. My dad was on vacation in New Mexico and my brother was at home in Austin. My mom was dead. My aunt and uncle were in town but avoiding Richards Park since my cousin was getting married in three weeks and they didn’t want to risk getting COVID. Thus, the only familiar faces I had seen that day were the tombstones of a dozen or so of my ancestors, as I had been strangely compelled to stop by the cemetery on my way into town. I don’t always do that, and the activity hardly aligned with the festive spirit, but it felt weird to go to the goat cook-off and not at least say hi to my mom.

My mother was born and bred in Brady, and we visited her hometown all the time, so the goat cook-off was just one more reason to do so. Once my dad was made an official cook-off judge, it became one of our family’s flagship events. Every Friday before Labor Day we’d make the two-hour drive from our home in Austin, sometimes bringing city friends who could marvel at this smoky display of rural quirk. We always stayed at my mother’s childhood home with my Uncle Bart, Aunt Bonnie, and Cousin Fred, who drove down from Dallas. The house was only a five-minute walk from the festival grounds, which allowed us to come and go if we got too tired, too hot, too dusty, or too rain-soaked. Some of my most memorable childhood epiphanies were cabrito-related, like when it dawned on me that there weren’t any statewide or national goat cook-offs preceding this one. The Brady folks had just made up the “world championship” part for fun. This clarified a lot about my life and the people I come from.

The First Annual World Championship Goat Cook-off, hosted in August 1974, was an effort to reinstate the old county fair. It was organized by the local Jaycees (a.k.a. the Junior Chamber of Commerce, a collection of young-ish local guys dedicated to fostering Brady’s civic and economic growth). They wanted something that could attract visitors to Brady and give local businesses a nice influx of cash. Modeling the event off the then seven-year-old Terlingua chili cook-off, the Jaycees picked cabrito because Brady was right smack in the middle of Texas’s “goat country” (this was before the area became so overrun with coyotes that it no longer made sense to raise anything smaller than a steer). They scheduled it for Labor Day weekend to coincide with some horse races happening at a track just down the road. Everyone hoped the whole affair would make Brady—a place so rural the local motel displayed signs reading “Do not clean birds in the room”—a must-visit destination for the state’s who’s who.

By the time I showed up to the party in 1986, the horse races were a thing of the past, but the World Championship Barbecue Goat Cook-off had turned into quite the to-do. Each year, hundreds of hopeful smokers parked ginormous barbecue pits in Richards Park, right on the banks of Brady Creek, bringing trailers, tents, campers, coolers, and lots and lots of beer. The smoking started on Friday night, with the official competition kicking off Saturday afternoon around four. The judges were sometimes herded under an old tin pavilion, though they often got set up on a huge flatbed trailer, five or six feet tall, parked in the center of the action.

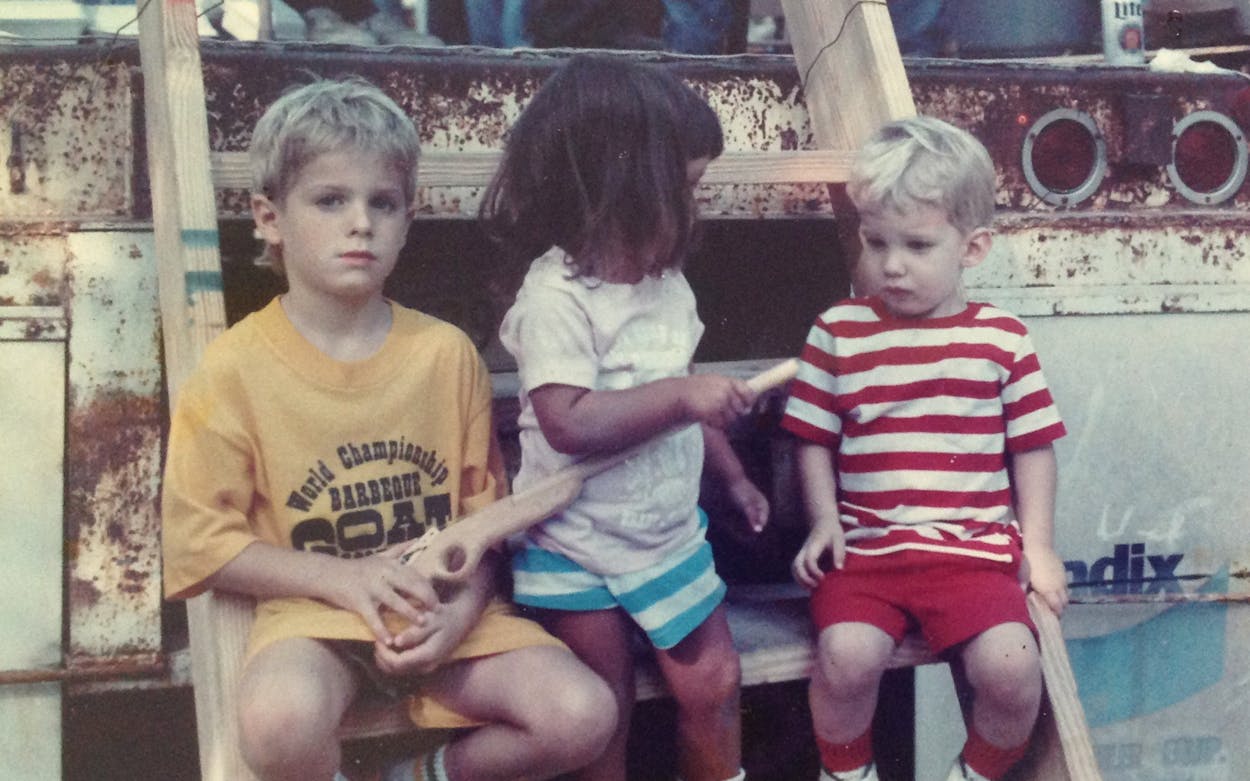

To protect the integrity of the judging, contestants dropped off cabrito in identical styrofoam containers differentiated only by the anonymizing numbers scribbled on their tops. When a particular container was disqualified, it moved from on top of the table to underneath it. This was an important detail for us kids, because we wouldn’t get in trouble for eating anything that was already on the ground. I spent a good chunk of those afternoons crawling from table to table tasting everything I could get my grubby little hands on. My father remembers eating some pretty bad goat during his judging days, but to me it was all delicious: a true delicacy, a sumptuous culinary adventure, probably because everything tastes a little better when it’s snuck.

Even so, the goat meat was not the biggest draw of the cook-off, at least not for the children. That was the fair, the dozens of booths lining the park, selling everything from T-shirts to homemade jam to toy guns that had been carved from wood and designed to propel rubber bands at actually pretty dangerous speeds. Every year, my brother and I were each allowed to pick out one rubber band gun; usually one of us would get something with a long barrel, while the other got something handheld, so we could switch off and share. We got in huge trouble if we were ever caught pointing them at each other, not just because the rubber bands could put your eye out but because when Dad was a kid his friend had been accidentally killed while cleaning a rifle, and Dad was very, very insistent that we never ever feel comfortable pointing something gun-shaped at another human being. It sort of worked, but mostly we just tried harder not to get caught.

The cook-off had been one of the McCullar family’s most beloved annual traditions, but like most every other aspect of our lives, it all changed when my mother died. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1994, and was gone a couple months after Labor Day weekend 1996. My dad stayed a cook-off judge for at least one more year, but eventually we phased out most of our Brady activities because it was too excruciating a place to spend time in. We stopped staying at my mother’s childhood home. The World Championship Barbecue Goat Cook-Off was no longer something I frequented, just something I told people about, usually to get laughs. City folk, Yankees, and any of the other nonrural Texans I’ve encountered find it incredible that such a competition exists at all. Between my thirteenth and thirty-sixth birthdays, I think I actually attended the cook-off only one time.

The most annoying thing about grief is the way it makes even good memories feel bad. I felt dread walking into Richards Park. If the scene were identical to those of my childhood, it’d be a painful reminder of all that I’ve lost. If it were dramatically different, it’d be a painful reminder of all that I’ve lost.

It turned out to be some mix of the two, and thankfully more entertaining than painful. As I strolled through the dusty grounds, I saw some inflatable bounce houses in the kid-friendly section. It was not the hastily constructed carnival attraction I remember almost throwing up in back in the day. In general, the park seemed safer than it used to be—cleared of all the rusty metal equipment my mom and I played on in our respective childhoods. I walked up and down the aisle of booths and saw no one selling rubber band guns to children, although there were at least two booths selling knives, and an opportunity for eighteen-and-over visitors to enter a raffle for what looked like a lime-green AR-style rifle. This was still Texas, after all.

The children I saw did not seem to realize how much they were missing out on. They were just happy to be at the park with their family and friends, satisfied with an inflatable Paw Patrol character taped to a plastic stick as their souvenir. It was, as always, an event defined by its groups: families, cooking teams, camping chair circles. I saw one RV with a generator-powered, forty-inch flat-screen propped up on a folding card table, broadcasting some sports game. There was one area that seemed like a real party, complete with string lights, cornhole, and a couple dozen adults and kids having a ball. There were as many good tidings in the air as there were enticing aromas of cooked goat, and the positive spirit rubbed off on me, even as I walked through the crowds alone.