More than a dozen lawsuits have been filed against Baylor University, and against certain members of the staff both present and former, stemming from the abuse scandal that the world learned about in August 2015. Most have been settled out of court for undisclosed dollar amounts. But there’s one exception: Dolores Lozano, a Baylor student from 2011 to 2014 who served as equipment manager for the school’s acrobatics and tumbling team—and who now serves as a Harris County justice of the peace—opted to go to trial in her suit. It named not just the university but also its former football coach Art Briles and former athletic director Ian McCaw.

Lozano alleged that she was abused during her relationship with former Baylor football player Devin Chafin. She sought to hold the defendants responsible for the emotional and physical distress she suffered. Her lawsuit argued that they neglected to carry out their duties under Title IX, the part of the 1972 federal civil rights law that guarantees equal access to education regardless of gender. To help the jury determine whether those parties are legally liable, several witnesses—including Briles and McCaw—were called to testify during the trial’s first week. (After Thursday’s testimony, Briles and McCaw were dismissed from the lawsuit, leaving Baylor as the sole defendant.)

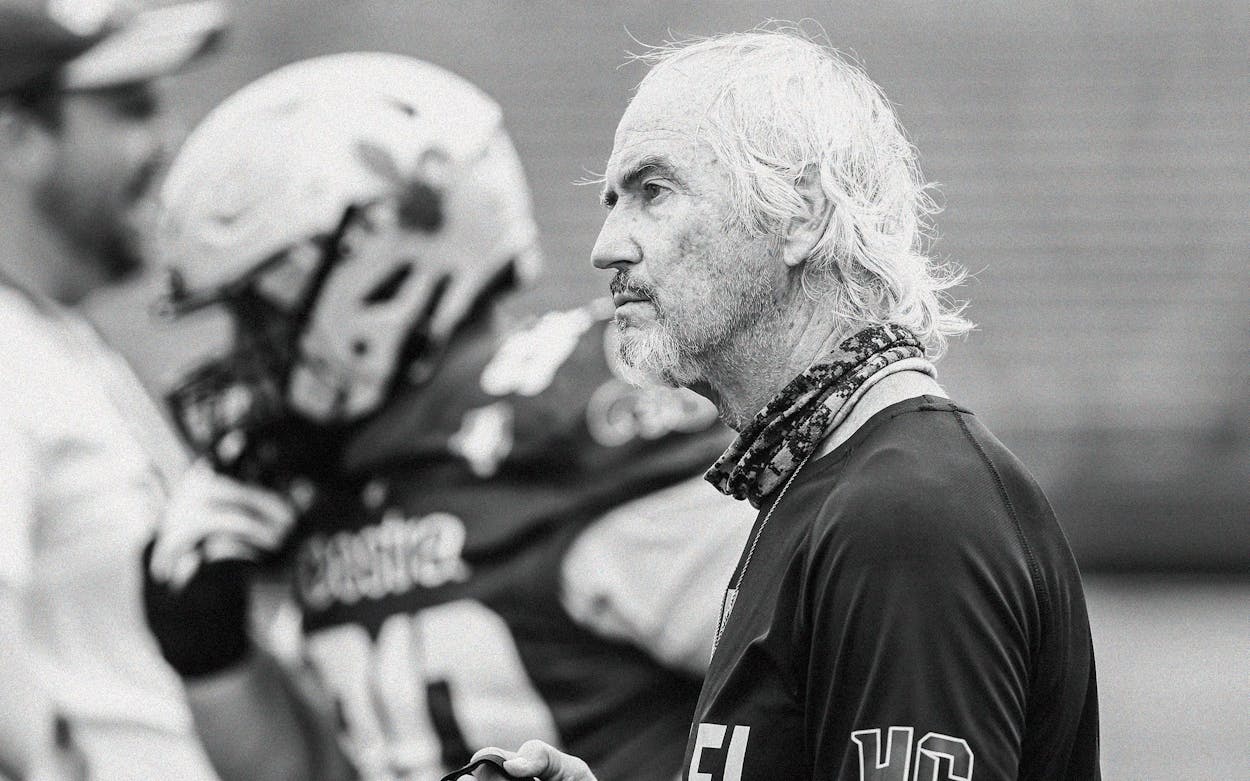

Briles testified on Thursday in the Waco courtroom of Judge Robert Pitman, a federal judge in the Western District of Texas. Taking the stand—now with a full goatee and hair whiter and longer than he wore it on the sidelines a decade ago—he answered questions from Lozano’s attorney Zeke Fortenberry.

Briles, during his coaching career, was well-known for his folksy demeanor and laid-back Texas charm, and those traits were on display during his testimony. He got a laugh from the jury when explaining how he made the jump from the leagues of assistant coaches to the University of Houston’s head coach in 2003. “Houston was dismal,” he said when asked about the team’s record of success prior to his tenure. “I got the job because nobody else wanted it.” But there were also some unusual moments during the testimony. Here’s what we heard in the courtroom.

Briles denied that he wrote his memoir.

In 2014, after Briles had led Baylor to two Big 12 championships and guided its first Heisman Trophy winner, Robert Griffin III, to the second overall draft pick in the NFL, his story—of a former high school coach who worked his way up to the national stage—was irresistible to the football-loving public. In fact, there were two books published that year about his journey. The first, Art Briles: Looking Up: My Journey from Tragedy to Triumph, was an authorized biography written by Dallas Cowboys staff writer Nick Eatman. The second was Beating Goliath: My Story of Football and Faith, a memoir cowritten by Briles and sports biographer Don Yaeger, published by St. Martin’s Press.

During the trial, Fortenberry asked Briles about Beating Goliath—and Briles claimed he had no knowledge of the book, saying that it was “written about me” and that he’d never read it. Fortenberry attempted to clarify, holding up a copy of Beating Goliath to ensure Briles hadn’t confused it with Art Briles: Looking Up. The coach insisted that he wasn’t mistaken. He was, he said, more involved in the publication of the authorized biography than in that of the memoir. He testified that he didn’t remember approving Beating Goliath or signing a contract for the book; he only grudgingly acknowledged that he had participated in a book signing for the memoir at the Baylor bookstore in 2014. When Fortenberry asked him if he was paid for the book, he declared that all of the money had been donated to charity, and when Fortenberry said that giving the money to charity didn’t mean that he hadn’t been paid, Briles insisted that he hadn’t.

When I described the testimony for Yaeger, the coauthor of the book, he was surprised. “Nothing about the way you reflected it could be further from the truth,” he wrote in an email on Thursday night. “I just reviewed the book contract with St. Martin’s, which was signed by Art and his agent received Art’s portion of the advance.”

Briles claimed he didn’t sue Baylor officials after he was fired.

A similar—albeit shorter-lived—dispute arose over a lawsuit Briles filed in December 2016 against three members of the school’s board of regents and former Baylor senior vice president and chief operating officer Reagan Ramsower. When Fortenberry mentioned that Briles had filed suit, the coach denied that he had done so. “I never did sue,” he testified. When Fortenberry began to question that assertion, Briles walked it back. “Or maybe so?” he said. “For defamation.” Briles then claimed that his lawyer, Stephenville attorney Ernest Cannon, had filed the suit, though it was unclear whether the coach was claiming that Cannon had done so without his awareness or consent.

The suit was dropped in February 2017; three months later, Baylor’s general counsel signed a letter, which the Fort Worth Star-Telegram described as an “about-face,” that publicly expressed support for Briles and claimed the school did not find him responsible for the scandal over which he had been fired. (The letter helped Briles get hired as a coach for the high school football program in Mount Vernon, Texas, in 2019.)

Briles referenced the contents of that letter during cross-examination, despite being instructed not to do so.

The rules of the trial meant that certain pieces of information weren’t allowed to be shared with the jury. This affected both sides—Lozano’s attorneys, for example, were barred from mentioning the $15 million contract settlement Briles received from Baylor in 2016. Briles and his lawyers weren’t allowed to present to the jury the contents of the letter from Baylor’s general counsel. Nonetheless, when Briles was presented with the letter during his testimony, he repeatedly referred to its contents—despite repeated sustained objections from Fortenberry.

“It’s a letter of exoneration,” Briles said, to which Fortenberry objected; when the judge sustained the objection and Briles’s attorney was asked to rephrase his question about the letter, Briles reworded his description. “It’s a letter from Baylor exonerating me,” he said, to another objection. Upon his third objection, Fortenberry asked if the attorneys could approach the bench, after which the document was removed from the witness stand and Briles’s lawyer moved on.

Briles argued about whether Chafin had “played well” when he returned to the team.

Briles has long maintained that, despite the scandal, no player who was charged with sexual assault ever played a down of football at Baylor after such allegations were made. That’s true—but Chafin, who was accused by Lozano of dating violence, did play for Briles in 2014 and 2015, after Lozano reported the incident to the university. The coach downplayed the significance of that decision when questioned.

“He played well,” Fortenberry said during the examination, and Briles disputed the claim. “Depends how you define ‘well,’ ” Briles responded. When Fortenberry noted that in 2014 Chafin scored eight touchdowns, Briles bristled. “What were his carries? What were his yards?” (Chafin carried eighty times that season for 383 yards, averaging an impressive 4.8 yards per attempt.) The following season, Chafin scored nine rushing touchdowns and one passing score and made 121 carries while maintaining his 4.8-yards-per-carry average. Briles’s implication seemed to be that Chafin, while he was allowed to participate, wasn’t a significant contributor to the team—a surprising assertion to make about a player who undoubtedly put points on the board for Briles’s squad.

In addition to dismissing Briles and McCaw from the lawsuit, Pitman also dismissed one type of charge—of gross negligence—against Baylor. Lozano’s lawsuit now exclusively against Baylor, on charges of negligence and violating Title IX, will continue next week.

- More About:

- Sports

- Art Briles

- Waco