This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Maybe it was the balmy air that made a Monday morning in late October seem like springtime, or maybe it was the rising economic indicators. But this was turning out to be a very good market, and Rubylee Richardson from Conroe was in a hurry to buy. She joined the thousands of other buyers marching toward a massive slab of pinkish-buff concrete that squatted like a cyclopean monument in a teeming sea of luxury sedans and Winnebagos. They were attending the Dallas Women’s and Children’s Spring Apparel Market, the biggest market of the year, and Rubylee and her colleagues strained to hear a distant voice. They listened for an intimation across the months that separated them from next spring, when the clothes they ordered this fall would meet the exacting eyes of their customers out in America’s heartland. And today that voice seemed to say that America would be buying.

Rubylee, in her early fifties, with no-nonsense, lightly curled dark hair, started the day with Halston. She and her beige-chemised assistant entered the salonlike fourth-floor showroom and were ushered into a smaller private room with burgundy carpeting that matched Rubylee’s J. Tiktiner print dress. Rubylee sat at the second of two small, round tables covered with blue-gray satin tablecloths and faced a rackful of Halston originals. Don Friese, a Halston vice president, began pulling dresses off the rack and methodically reciting product descriptions, stock numbers, and prices.

“You know, with the depression and all the bad news now, people want color,” said Friese as Lisa, his towering brunette model, posed beside him in a bright blue dress with a patterned yoke. Rubylee rejected the dress with an almost imperceptible shake of her head, and Lisa left the room to change. Next, Friese held up a black dress with a shawl collar and a wholesale price of $300. “I want that in a four,” said Rubylee to her assistant, who made the entry on a clipboard-mounted order form. Then Lisa returned in a yellow ocher dress with a yoked back. “Let’s buy this one for Andy Delery,” said Rubylee.

In twenty minutes Friese had gone through the line and taken an order for $3400 worth of Halston. On the racks at Rubylee’s in Oak Ridge Plaza Center near Conroe, that merchandise would be worth $6800, assuming that Rubylee could sell it to the Andys and the Peggys, the individual size 4s and size 10s that she had in mind. And while Rubylee could risk being wrong every now and then, she couldn’t afford to be wrong very often.

The Dallas Apparel Mart is the world’s largest wholesale fashion market under one roof. It has 1.8 million square feet of space, with nearly 2000 separate showrooms that handle more than 10,000 individual apparel lines—everything from designer evening gowns to breast prostheses—and it has been expanded so ambitiously that flying buttresses now prop up the additions, as if the Apparel Mart were the modern, horizontal version of the medieval cathedrals that once aspired relentlessly toward the heavens. It is a place where every year, in ten furious major market weekends, 100,000 buyers like Rubylee order an estimated $2 billion worth of merchandise. It is a place where the fashion consciousness of New York and Paris can be transmitted to the heart of America, a place where little people with big dreams can make sudden fortunes and lose them just as suddenly, a place where in the long run there is no such thing as an easy buck.

Two Kinds of People Wear Calvins

In a business in which survival is often tenuous and the old order changeth constantly, new beginnings come regularly. For the spring market that beginning came at 9 a.m. on the next to the last Friday in October. Disembarked from taxis, limos, buses, hotel courtesy vans, and their own cars and campers, the first trickling hundreds of what would become thousands of buyers were already piled up at the turnstiles in the Apparel Mart lobby. Distinguished by their blue buyer identification badges, they filed in and milled around the escalators that would, for the next five days, pump them through the building like a steady stream of life-giving corpuscles. As the buyers paused to leaf through their thick hot-pink Official Women’s Buyer’s Guides, half a dozen closed-circuit TV sets on blue-aproned stands gave them a first dose of pseudo-personalized marketing appeals. “Mother looks for quality, a name she can trust,” said a motherly voice from the screen.

To watch the buyers enter was to realize that fashion has no absolutes. There were women in cream summer jackets and in dark fall Ultrasuede blazers, young women in dowdy but bright pastel separates and mature women in subtly shaded matching skirts and blouses with contrasting blazers, matrons in polyester pantsuits and swingers in tight leather jeans. “Our customers are intelligent, they’re smart, they’re bright,” said the chairman of the board of the Charlotte Ford Jean Company from the TV screen. There were balding men in cowboy boots and three-piece suits, middle-aged men in wing tips and corduroy jackets, young men in blue blazers and jeans, men with razor-cut hair in double-breasted Adolfo suits with Bally shoes, men with blown-dry hair in tasseled loafers and velour sweat shirts. “There are two kinds of people who wear Calvins,” cooed teenage actress Brooke Shields from the TV screen. “Those who want to remember, and those who want to forget.” There were women with short feathery hair, long curly hair, teased and sprayed hair, gray hair, bleached hair, and dyed hair. “You don’t stop being a junior when you become a woman,” said a bouncy, cheery voice from the TV screen.

“The Apparel Mart has been expanded so ambitiously that flying buttresses now prop up the additions, as if the Apparel Mart were the modern, horizontal version of the medieval cathedrals that once aspired relentlessly toward the heavens.”

As if drawn by some inexorable osmotic pressure, the buyers began to percolate through the building’s six floors and twelve miles of corridors. The showroom owners and line representatives waited at their doors in nervous anticipation; their chummy exchange of details both personal and mundane became an indecipherable cacophony, like the chatter of a treeful of tropical birds. But when the first buyers came into view, they were greeted like fellow travelers in a vast and trackless desert. “Come on in, girls!” called a stout, middle-aged showroom owner to a couple of nondescript buyers with carefully lacquered coifs. “Where’re you girls from?”

“Bowling Green, Kentucky,” the buyers said assertively.

“I’ll get the Bowling Green salesman for you!” the showroom honcho chortled as he swept inside his first customers of the new market.

As Crow Flies

In a way, John Stemmons was the first patron of the Apparel Mart. From his office on the twelfth floor of the Stemmons Tower, the seventy-year-old multimillionaire, a big, silver-haired man in a blue-striped shirt and a pale green print bow tie, looked down through a wall of glass and surveyed the Stemmons Freeway, the vast southwestern flank of Dallas that his father reclaimed from the Trinity River, and the empire that Trammel Crow built on that land. To the south stretched Crow’s Market Center—the Apparel Mart, the Decorative Center, Market Hall, the Trade Mart, and the colossal World Trade Center, all of them of Crow’s conception, all of them built on Stemmons’s land.

When Stemmons met Crow back in the early fifties, Crow was in the grain business in Dallas. At the prompting of a group of local decorators, he suggested building a wholesale decorators’ market on Stemmons’s land, using the land as equity for the bricks and mortar. Stemmons saw in the younger man “a unique capacity to discipline himself,” and he agreed to a joint venture. He put up the land, Crow arranged temporary financing, and the buildings began to go up. The Decorative Center opened in 1955, the Homefurnishings Mart in 1957, the Trade Mart two years after that, Market Hall in 1960, and the Apparel Mart in 1964. During this period, Crow, sometimes accompanied by Stemmons, researched other markets around the country and often lured their tenants to Dallas; on occasion both men were thrown out of their competitors’ buildings. But Crow’s vision of a vast marketing complex prevailed, even when Stemmons, a very conservative businessman, balked at the interest rates the note on the World Trade Center (finished in 1974) would carry. Stemmons suggested that Crow buy him out if he wanted to go ahead with it, and Crow did—after offering more than Stemmons was asking.

Today the signature of Trammel Crow is all over the Apparel Mart. It was Crow who decided that each of his buildings should have a central atrium, a vast core where harried business people could rest their weary psyches, an idea that was later borrowed by the Hyatt hotels. And the Apparel Mart’s most prominent feature is the Great Hall, an enormous landscaped and terraced cavern with undulating biomorphic walls that doubles as contemplative space and a showcase for fashion extravaganzas. Crow also made some expansions—the West Atrium, essentially an adjoined building wrapped around a gleaming high-tech core, and floors five and six, which bulge over the top of the original structure like thick icing on a massive cake. Even now, Crow is talking about adding a new wing to the building, an international men’s wear section that will further extend the scope of both the men’s and the women’s markets. Crow also put his children to work in his market center, and many people feel that his red-haired, 27-year-old daughter, Lucy, has added professionalism as chief operating officer of the Market Center.

But while Trammel Crow built a bridge between one of Dallas’s oldest and most conservative landholding families and the cosmopolitan apparel industry, the real business of the market is too microscopic in its detail and too enormous in its sum to have any one person’s name on it.

Norman’s Conquest

Within Trammel Crow’s merchandising empire there are many smaller, autonomous empires, and the House of Grunsfeld is just one of them. On that first Friday afternoon of the spring market, Norman Grunsfeld surveyed his empire from a vantage point in his oak-paneled second-floor office. By monitoring the four separate views of his aisle-long first-floor showroom that were being transmitted to the closed-circuit TV to the left of his desk, he could see that his 35 salespeople were ready for a big market. Some customers were already writing orders.

Norman runs what he calls a “high-profile operation,’’ which starts with Norman himself, an exceedingly active and gregarious Robert Redford look-alike. He favors trimly tailored, European-cut suits, covers the walls of his office with signed photos of sports superstars, congressmen, and U.S. presidents, conducts business from a plush swivel chair, and owns a copy of The Power of Positive Thinking autographed with a personal note from his friend Norman Vincent Peale.

The House of Grunsfeld has five thousand square feet of floor space, recently redecorated with $140,000 worth of chrome and brown cotton Breuer chairs, gray-beige carpet, and taupe paneling with the House of Grunsfeld coat of arms affixed here and there. The house handles eighteen lines of junior and missy sportswear (including an in-house T-shirt line) and merchandises a diet plan and the Grunsfeld Gold jewelry line on the side. The firm will do about $12 million in gross sales this year and will pocket the standard 10 per cent commission. But like most Apparel Mart magnates, Norman Grunsfeld hoed a long row to get where he is, and he takes nothing for granted.

When Norman graduated from Highland Park High School in 1955, he had a West Point appointment practically in the bag. But he was already married at age 17—he sired four children before he was 22—so he went to work. At 18 he was peddling slacks out in West Texas for the Haggar Company; at 26 he got into women’s wear with Stacy Ames, a division of Bobbie Brooks, Inc.; at 28 he was national sales manager for the Tribute Dress Company; and at 30 he had his own business manufacturing missy dresses. But it was never enough, and one day Norman had to take stock of himself. “I pretended I had just died,” he says, “and I thought about what people were going to say about me.”

When he looked at things that way, Norman decided he didn’t want to be remembered as a small-time manufacturer struggling against the financial giants who dominate the field, and he didn’t want to be backed by someone else’s money, either: “I didn’t want to be owned.” He decided right then that wholesale selling was the great void in the apparel business, and at age 32 he jumped into it.

Norman and his partner, Darryl Rausin, put up $1250 each and rented a six-hundred-square-foot showroom five days before the 1971 fall market, although they didn’t as yet have any lines to represent. Two days before the market opened, however, they picked up four lines, and by the time the market closed they had sold $70,000 worth of clothes, most of it from a new division of a major manufacturer. Then the most terrifying nightmare of the wholesale selling business became reality. The division folded, leaving Norman’s infant company with a sheaf of undeliverable orders and some highly irritated clients. It looked like the House of Grunsfeld was going to collapse like a house of cards.

Norman had a survivor’s instinct, however. He sued the parent company, won 100 per cent restitution, and got the company to send letters of apology to each of his clients. From then on Norman never looked back. By chance he met Philip Iselin, president of the New York Jets and owner of eight apparel companies, and took over national sales for some of the Iselin-owned lines. He acquired showrooms in the Atlanta, Charlotte, Los Angeles, and New York markets. Then, sensing the growing importance of the Southwestern apparel industry, he became concerned about strengthening his base.

“ ‘These guys are all alike,’ the model said. ‘They wear jeans, have Rolex watches, drive Mercedes, and talk with New York accents. They think it’s a big deal to go to Calluaud’s for dinner. And they all want to go to Cowboy, but they won’t admit it.’ ”

That’s when Norman started working on his dream, a dream of sheer physical dimension: he wanted to control an entire hallway at the Apparel Mart. It became an obsession. He sold his showrooms in the other cities and took over the leases of showrooms on his hall whenever someone moved; every time he acquired contiguous rooms, he knocked out the intervening walls. He waited and cajoled, and sometimes he planned his takeovers like a chess master setting up a spectacular attack thirty moves in advance.

There was one long-term holdout, an accessories salesman, who resisted all of Norman’s attempts to buy his lease. Norman, having heard that accessories were going to be consolidated on the sixth floor, bought the lease on a sixth-floor showroom and held it, unused, for an entire year. Then, when the accessories man saw where his business was moving, Norman made an easy trade. And now his office holds a fragment of Sheetrock marked “8/18/79”; on that day Norman’s showroom finally stretched all the way from aisle G to aisle F, and an Apparel Mart dream came true.

Now Norman was looking forward to a good market that would take him closer to his next goal: building an organization so strong, so vital, that some conglomerate would buy him out and make everybody involved in the House of Grunsfeld rich. Then Norman plans to write books (he has already finished his first, The Fourth Coming) and devote more time to Normandy, his three-year-old son by his second wife, Karon. “My goal,” said Norman, “is not just to make money, but not to be sad.”

The Unimpressed Model

Late Friday afternoon, the aging owner of a string of eight children’s wear shops based in Little Rock, Arkansas, sank back into a couch on the second-floor landing. He had been in the business for thirty years, and he had been coming to markets in Dallas since before the Apparel Mart was even built, back when the nucleus of the business was the old Merchandise Mart on South Ervay. “You come back after a year and find that people you have bought from for twenty-five years are dead,” he said wearily. “When so many people you know have died, you realize that you’re going to go soon, too.”

At five, many of the showrooms began serving complimentary drinks. In one third-floor designer showroom, a twentyish blonde model rejected a dinner invitation from one of the line owners, a thirtyish, disco-generation New Yorker whose life was a lucrative but nomadic routine of traveling to markets all over the country. The model was unimpressed. “These guys are all alike,” she said. “They wear jeans, have Rolex watches, drive Mercedes, and talk with New York accents. They think it’s a big deal to go to the Mansion on Turtle Creek or Calluaud’s for dinner. And they all want to go to Cowboy, but they won’t admit it.”

With such introspection, desultory conversations, and the Southwestern Apparel Manufacturers Association’s fashion show in the Great Hall, day one of the spring market ended.

You Gotta Know the Territory

Like a city, the Apparel Mart has neighborhoods of distinct character and economic status. The first floor includes lots of conservative, moderately priced lines, while the west end of the second floor features the latest in flashy junior sportswear. The third floor is dominated by the high-rent neighborhood, the Group III couture designer section; many of these showroom owners have cut stairwells in order to expand their spaces into the fourth floor. The fifth floor is largely devoted to men’s wear, and during a women’s and children’s market some of the aisles there are so dark and ominously silent that it is easy to imagine muggers lurking around the corners. The sixth floor has lingerie, jewelry, belts, handbags, the office of a local fashion publication, and the sales office of a computer marketing firm. There are also highly specialized ghettos, like an aisle devoted to merchandising aids (garment labels, custom paper bags, mannequins, and mechanized Santa Clauses) on the fourth floor; several aisles for sizes 12 through 20 fashions (“big, beautiful women’’) on the second floor; and the fifth floor “Territory,’’ where Western wear is peddled from dozens of showrooms with mock Dodge City facades incongruously painted in lurid purples, oranges, and electric blues.

Inside the showrooms, the basic plan is simply racks and rows—racks of clothes and rows of chairs and tables where buyers write orders while they are being shown the lines. But within that basic theme the variations are infinite, and each showroom is a little principality of individual taste. There are bentwood chairs, plastic folding chairs, schoolchildren’s chairs with attached writing platforms, director’s chairs in every available color, Early American chairs, modified Empire-style chairs (very popular in Group III), and a whole galaxy of Breuer chairs—cane, satin, wicker, and leather Breuer chairs; plush padded Breuer chairs; black, white, and brown cotton Breuer chairs; and Breuer chairs with padded cotton seats and cane backs. There are Formica tables, Parsons tables, sculptured wooden tables, chrome and glass tables, round tables with tablecloths, wooden tables with embossed leather tops. There are ersatz architectural accents like cast-iron railings, shingled canopies, scalloped cloth awnings, brick pilasters, and scrolled window moldings.

There is Martha’s Fashion Lane on the third floor, with a three-foot-wide section of an oak tree squeezed between ceiling and floor so that it looks as though some maniacally persistent tree is growing right through the building. There are the sumptuous salons in Group III, with kitchens, maids, gilt-framed mirrors, suedelike pile carpets, and rows of track lights. There are the Esprit Showrooms, the latest thing in junior presentation, which surround the intersection of two aisles and have been turned into a glittering, glass-walled boutique. A reception area with overstuffed sofas and American Gigolo decor has been carved into the southeastern corner of the intersection, and a wall-size rear-screen projection unit presented an enticing jiggle show with girls romping on the beach in wet Esprit T-shirts. Above the screen was a digital clock. At the north end of the boutique a blue neon “Club Esprit” indicated the location of the bar.

A Nightgown in Super Large

Tenacity, not showmanship, is the real key to survival in the apparel trade, and Maurice Taub, 25 years in the business, has tenacity. His showmanship, however, is largely confined to the black lettering—“Maurice Taub, Exotic Lingerie”—on the sliding glass door of the showroom he shares with Carroll J. Papahronis, a wholesaler of nurses’ shoes and uniforms. But of course Maurice had placed some eye-catching merchandise just inside the entrance, including a mannequin torso in a transparent red lace teddy and a pair of tiny bikini panties with an embroidered $100 bill over the crotch.

Maurice wore somewhat modish tortoiseshell glasses and a gray sport coat, and his receding gray hair was brushed straight back. A kindly, soft-spoken gentleman, he seemed like the kind of guy who would own a small coin shop. But Maurice’s father had been in the bra business, and when Maurice tired of the daily skirmishing in New York City and came to Dallas 21 years ago, he was already in the lingerie business. He was a “drummer,” a salesman who toured Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Arkansas drumming up business. In those days Maurice was embarrassed to show his exotic merchandise to women, so he would go into the store, hang up his samples, and walk away.

When Maurice first heard the publicity about the new Apparel Mart, he was receptive to the idea. Trammel Crow’s representatives were trying to get the lingerie people in on it, too, and they showed Maurice the blueprints for the proposed building. Maurice reasoned that a market showroom would keep him off the road during at least the four market weeks and that he would probably get a lot of new customers from small towns he had never even heard about. So he signed a lease for a second-floor showroom and became one of the Apparel Mart’s charter tenants.

In the sixteen years that Maurice has been at the market, his business has changed. He has just moved from the second floor to the sixth, where the lingerie business is being consolidated. His showroom, with rust-colored pile carpet and beige walls, rents for $450 a month, and he might expect to do $30,000 in business in a single market week, of which he gets the usual 10 per cent commission. He still travels for thirty weeks a year and still does 60 per cent of his business on the road. But the market has become more and more popular with buyers, and Maurice has seen much more interest in his products as parochial attitudes disappear in even the most isolated communities. “Because of communications,” said Maurice, “there’s no such thing as a small town anymore.” Of course that has also meant more competition from new entrants in the field, and Maurice has had to fight to maintain his share of the market. “You’ve got to keep moving in this business,” he said. “If you stop, there’s always someone there to step on your toes.”

At 9:30 on Saturday morning Maurice Taub sat in a plastic chair behind one of his Formica tables. He had nylon bras—black, white, nude, lace, strapless, and convertible, all in sample size 34B—laid out on a tabletop, his rack of nighties, peignoirs, girdles, and sedate cotton print dusters behind him. The $100 bill panties and the red teddy were in place. Suddenly he called to a couple strolling by. The man was bald and quite large, wore a plaid sport coat, and had a gold arrowhead on a chain around his neck. The woman was even larger than her husband, and her rust-colored raincoat seemed almost like a small circus tent. She ran a large-size shop in Laredo, and she didn’t need any bras or girdles; in fact, she had just gotten a shipment from Formfit and was overstocked. She said she was just going to have to come back later, which is the buyer’s universal euphemism for “I’m not at all interested, but since I may need to deal with you at some point in the future, I won’t tell you to jam it.” Maurice, however, was intent on some gentle persuasion. “I have some nice girdles and peignoirs,” he said, and although the buyer didn’t need any peignoirs either, she guessed she could look at some of the nightgowns that Maurice was already pulling off the racks.

The nightgowns, filmy beige or pink with sheer boudoir jackets, ranged from $120 to $150 a dozen, “but you can price them all the same,” said Maurice. Each lot of a dozen was sized 3-6-3, which is ordinarily to say that three were size small, six medium, and three large. Here the buyer balked. She liked the merchandise, but she only needed the large pieces; the rest of the lot would be worthless. Maurice straightened things out quickly. In this case, 3-6-3 didn’t mean small, medium, and large; these nighties came in lots of large, extra large, and super large.

Maurice started writing up the sale on a pink order form. The buyer wondered if he had a corselette, a combination panty girdle and bra—large size, of course. He didn’t, but he could recommend a place in New York that did. Maurice wrote down the name for the buyer, and she and her husband left, quite pleased. “It’s interesting how many great big women like sexy things,’’ said Maurice when they had gone. “About twenty-five per cent of American women are heavy. That’s a significant portion of the market.”

Even with the developing heavyweight market, Maurice still had some slight qualms about the future. He talked about a system in Kentucky that allows horseplayers to place bets via a special device hooked up to their television sets, and he suggested that the system could be adapted to apparel merchandising. A manufacturer could show his line on the video screen, and retailers could place orders right back into the tube. “Someday,” said Maurice with surprising good humor, “there may no longer be a need for salesmen.”

The Designer Jean Blues

The future is always an area of opportunity in the apparel business, and on Saturday afternoon Bill Consedine was contemplating that future. He knew that his own future was with Sunshine, his vertically integrated international designing, manufacturing, and marketing setup for what he described as “bold, bright tropical prints.” Consedine, a bearded, articulate, dashing-looking man, had come to Dallas to ease his line into the Apparel Mart, a step he was taking cautiously. “The tendency in this business,” he said, “is to overexpand and not keep up with accounts.”

After Consedine graduated from Dartmouth in 1960, he spent ten years in the textile manufacturing business and finally sold his firm to some Japanese in 1972. He went on to start his own line, knowing that he was entering an economic region of boundless vistas and precarious footing. “It’s a business that’s easy to get into,” he said, “and very difficult to stay in.”

Today Consedine makes his headquarters in Honolulu, where he and his partner employ their own fabric designers; they have the fabric printed in Japan, the only place they can get the sixteen-color process that gives the fabrics the subtle gradations they like; and he owns manufacturing operations in Hong Kong and San Francisco. He also has a very aggressive grasp of the dynamics of his business, and on Saturday afternoon he was thinking about a new trend that he was certain would affect his future.

“There’s going to be a tremendous blowout in the jeans business,” said Consedine, and he explained why. The business of designer and signature jeans—locally, Willie Nelson, Mickey Gilley, and J. R. Ewing are new additions to those lending their names—has produced a huge cash flow, but much of that money has been plowed back into advertising while other bills are settled less quickly. Added to this financial overextension is market saturation. “How many pairs of designer jeans can somebody have in their closet?” wondered Consedine, who saw signs that the limit had already been reached. “Look, they now have Brooke Shields advertising jeans on television. That’s because they keep having to move down to lower age groups to find a market. The next thing I’m looking for is three- or four-year-old kids modeling jeans on TV.” Worse still, the whole business, according to Consedine, is heavily financed by Arab money, and their interest is immediate cash flow, not the future of a line.

“Jeans are already backing up,” said Consedine. “When the market finally gets hit, it’s going to make a deafening roar. And the dress business is going to come back strong.” Sunshine was already gearing up an expanded dress line, working with fabrics more suitable for dresses, designing prints more appropriate for dresses. “In this business,” said Consedine, “you’re only as good as next year’s line.”

As Saturday’s buying ran into its last hour, there was a minor crisis in the third-floor Calvin Klein showroom. They were running out of what had become a very hot promotional item: Calvin Klein signature diaper covers in blue denim.

Beige Body Stockings and Fanciful Scenes

By six o’clock on Saturday a privileged and expectant crowd had overstuffed the Fashion Theatre; they sat in neat rows surrounding the runway, they jammed the balcony, they sat on the steps leading to the balcony. These were the buyers who had finagled tickets to Leon Hall’s Group III show, and they had come to see the best designer clothes showcased by the Apparel Mart’s legendary fashion impresario. Within minutes they would see an elegant, carefully machined procession of women and clothes, and if the chemistry was right, if something clicked, then a single garment in the pageant of hundreds could draw buyers to a showroom as if they were a swarm of insects lured by some powerfully intoxicating pheromone. And Leon Hall, of course, understood this quite well.

Leon was born 34 years ago in South Carolina and grew up in New York, which may be why some people accuse him of speaking with a Southern accent for the benefit of Texans and adopting a New York accent when he does shows in New York. Leon studied costume design at New York University, worked as a go-fer in several Paris couture houses, and met Apparel Mart fashion director Kim Dawson fifteen years ago while he was a fashion director for the Sanger Harris beauty salon in Dallas. Leon started backstage, but by the time Group III originated six years ago, he was the obvious choice to put designer clothes in the spotlight.

From then on, Leon and Group III came up in the world together. “We really romanced the top designers to get them down here when Group III opened,” remembered Leon. “Now they’re on a waiting list.” Where Leon once had to beg showroom owners and line reps to put their clothes in the show, today they clamor to place garments in Leon’s productions at a fee of $60 per piece. And where crowds were once sparse at free shows, today the $5 tickets are practically as scarce as Super Bowl ducats; starting in January, the Group III show will have to be repeated to pacify buyers who couldn’t get in the first time. And Leon is now an Apparel Mart institution.

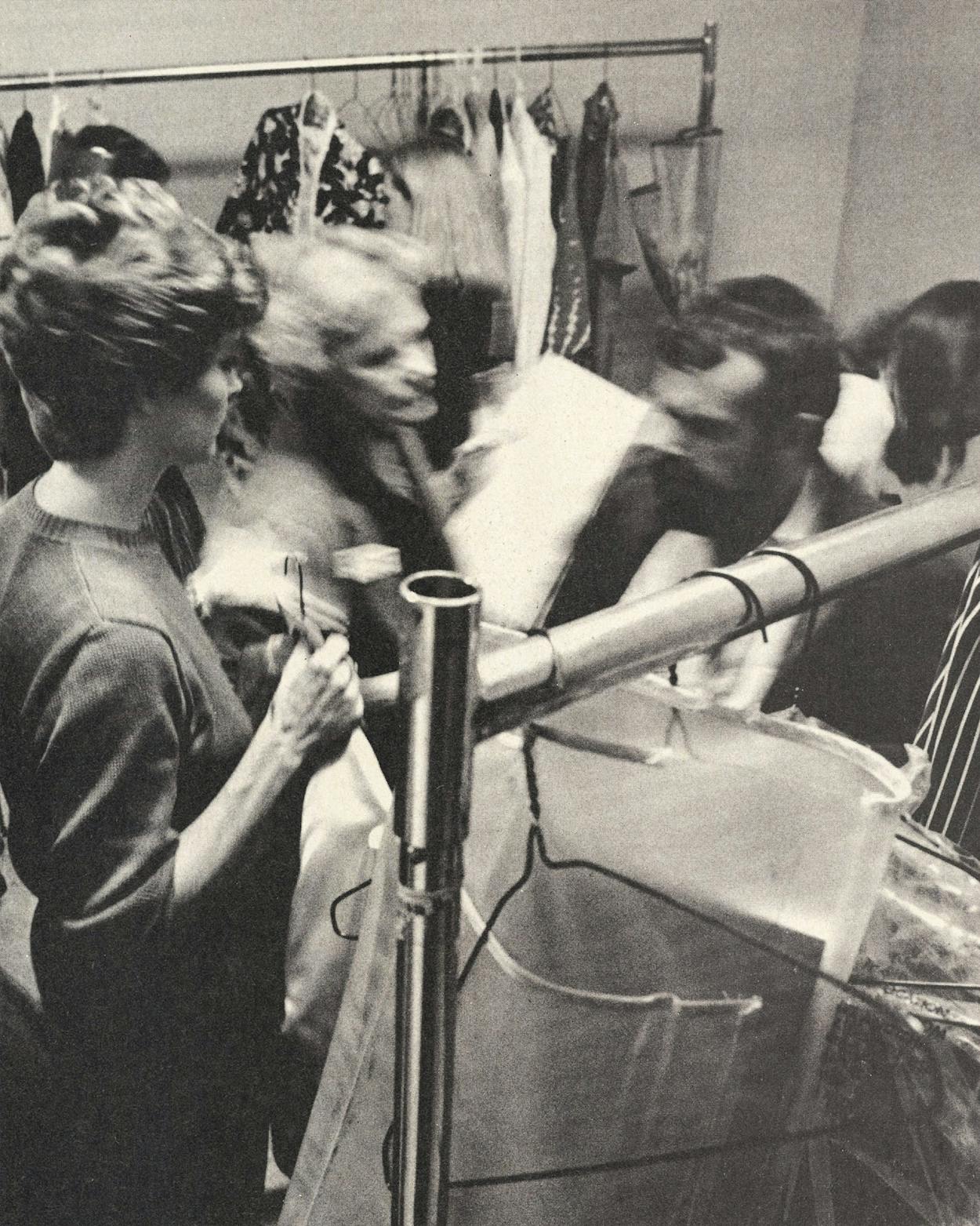

At six o’clock Leon was still backstage tearing through racks of clothes while six or seven members of his support crew milled about. Models wandered around in beige body stockings or nude half-slips pulled up over their breasts, and Dallas makeup star Aki was putting on some finishing touches in the dressing room. Kim Dawson cruised by looking as radiant and serene as a fairy godmother interceding in some dire personal calamity, and Albert Nipon, the hot, hot New York designer of the moment, passed by virtually unnoticed.

“Let me show you all how simple this is,” Leon barked like an annoyed schoolteacher, although what he was doing could hardly be considered elementary. It had really started Friday morning, when Leon and five assistants roamed Group III, culling the two best garments from each showroom. Since all of the samples are one of a kind and are needed in the showrooms during the day, the stock numbers were recorded in the morning, and at six Friday afternoon the clothes were collected and brought to Leon. He then picked through the 250 or so garments looking for fashion themes—a certain color, fabric, type of jacket, or perhaps silhouette—that were then arranged into seventeen separate and sometimes quite fanciful scenes. Next Leon spent until about eleven o’clock planning a final sequence for the garments in each scene, and then he brought in his four fitting models—one small, one medium, one medium tall, and one tall. These women gave a rough estimate as to who among the thirty or forty models in the show could wear what, and they also knew the other models well enough to keep, for example, beefy arms out of a sleeveless dress or scrawny legs out of shorts. By 2:30 a.m. Saturday each garment had been assigned to a model, and a master fitting chart had been prepared that would show each model the exact sequence of her trips down the runway. At 8 a.m. Saturday the samples were taken back to work in their respective showrooms.

At two on Saturday Leon met with his sound man, Dave Anderson, and selected music from a collection of cassettes assembled months in advance. “I’ll hear a piece of music,” said Leon, “and it might remind me of raincoats, or I’ll think it sounds like furs.” At four in the afternoon the clothes were picked up again, and beginning around five o’clock Leon went through the bunch, making sure that each garment was intact and in order and adding about 25 last-minute entries to the show. He was still doing that at six.

Ringmaster Kim

Meanwhile, Kim Dawson and Sheila Davlin were getting ready to do their shtick. Kim was wearing a Davlin—a long embroidered oriental print dress with a quilted beige satin jacket—which was appropriate since Sheila was guest designer for this Group III show and Kim, against some opposition, had had a lot to do with that.

Sheila Davlin was a real rags-to-riches-to-rags story, and if things went well in the next twenty minutes or so, she might be on her way to adding a final riches to the saga. A slender brunette, she was a Boston native who went to New York as a freelance fashion model, married the owner of a Boston oil pipe-fitting and valve business, and ended up in Opelousas, Louisiana, when hubby Irwin moved his highly lucrative concerns down there.

In Opelousas Sheila entertained herself by collecting richly brocaded and embroidered fabrics—many of them antiques—from the Orient and other exotic locales that she visited with her continent-hopping husband. The fabrics piled up in Opelousas, and finally Irwin issued an ultimatum: do something with them or stop collecting them. From that impetus Sheila developed a cottage industry employing forty native Cajun seamstresses to turn her fabrics into handbags, jackets, dresses, quilts, pillows, and wall hangings; soon she had to circumnavigate the globe every couple of months to replenish her stock of fabrics. Today she has showrooms in the Dallas and Miami markets and is carried by prestige retail outfits like Bonwit Teller and Neiman-Marcus. But some people still didn’t accept her as a bona fide designer, and Sheila wasn’t helping things by cheerily volunteering that she couldn’t sew or draw. Sheila had established a name, but she hadn’t as yet established a reputation. For a designer, that could be the difference between bucks and big bucks.

Kim Dawson, on the other hand, had a real affinity for another woman in a tough, male-intensive business. After all, Kim herself had come a long way from her home town of Center, where she had been a high school cheerleader in the early forties. After high school she had gone to Dallas, where she attended Draughon’s Business College and worked at North American Aviation. Then it was on to Washington to work on the staff of Senator Tom Connally. There Kim was the top seller in a war bond drive, which resulted in her meeting talent agent Harry Conover, who suggested that she come to New York to model. Next it was Paris, where Kim, a big rawboned country girl with reddish-blonde hair, became part of the first wave of exotic American models to invade Europe.

But when Kim started retracing her footsteps, she found that she didn’t like the pace of life in New York, and she returned to Dallas and went to work for Neiman-Marcus. While modeling at Neiman’s she taught at the Barbizon School of Modeling; then she tried acting on the West Coast. She married George Dawson in 1952 and began producing three children.

By 1960 Kim was back in business with her own talent agency in the old Merchandise Mart, and in 1964 Trammell Crow asked her to serve as Apparel Mart fashion director, at the time a rather nebulous promotional position. At first that was a pretty simple combination, but as more and more Apparel Mart shows were produced and her agency grew into a multimillion-dollar business representing more than five hundred models and entertainers, Kim became a sort of executive producer. “I’m the ringmaster,” she said. “I know that sounds glamorous, but I work like a dog.”

Despite the fact that Kim has become a major force in the talent and fashion business (she infuriated New York “model wars” antagonist Johnny Casablancas by refusing to get excited about his recent “challenge” to her preeminence in the Dallas market), she clings to the common touch like a lone shipwreck survivor clutching the last remaining piece of flotsam. Kim finally, a few months ago, changed the decor of her first-floor agency offices from cut-rate motel to a reasonable facsimile of contemporary advertising agency chic, but she still has her tiny office, its whitewashed walls covered with decidedly uncorporate art and knickknacks. And she doesn’t think that it’s her business to thrust design judgments on the market. “There’s no such thing as bad-looking merchandise,” she said, “only bad-looking models.”

That attitude, as the Group III scuttlebutt had it, explained why Kim had pushed Sheila Davlin as guest designer over the opinions of some people who thought that now was the time for the Apparel Mart to be making more aggressive design statements. Sheila was from a neighboring state, she had gotten her start in the Apparel Mart, she was a woman, she was gathering a following, and even if she wasn’t Karl Lagerfeld, in this case pure fashion was less important than more closely held values.

Kublai Khan Meets Busby Berkeley

As it turned out, after Kim had introduced Sheila and the houselights came down and the stage lights went on, Sheila’s stuff looked very good. That was in part due to Leon, who had visited Sheila with Dave Anderson three months earlier and selected some very dramatic oriental music to accompany the visions that had danced in his head. “I thought of a Roman march with two slave girls,” said Leon later, “Kublai Khan, Shangri-la.” And so they came, two models with wide, shallow baskets bearing Sheila Davlin accessories, other models in the imperial splendor of brocaded and embroidered evening clothes that were sometimes extravagant, sometimes as clean-lined as Japanese Noh robes.

Leon, now dressed in a light brown suit and tasseled loafers, had emerged from backstage and was standing right behind Kim and Sheila, next to a curtain that covered a sliding glass door that led to a terrace overlooking the Great Hall. Just then, the sound of music came blowing through the open glass door. Leon looked perturbed, and he went over and closed the door. Not only was the music distracting but it also meant that Dwight Byrd’s $75,000 Gloria Vanderbilt for Murjani extravaganza was beginning in front of a packed house three floors below.

Leon Hall and Dwight Byrd were not exactly rivals—in fact, they sometimes helped each other out backstage—but they represented a rather stark aesthetic dichotomy in their approaches to the showing of fashion. If they were painters Leon would be a realist, a believer in the literal interpretation of a particular look. “I want a perfect statement,” he said. “Perfect makeup, perfect hair, a perfect fit. I want the buyers to see instantly how that dress will look in their stores. I like to show fashion in its purest form.” Dwight, on the other hand, would be an abstract expressionist. “I don’t say, ‘Buy this and you’ll look like this,’ ” he said. “I say, ‘Buy this and you’ll feel like this.’ That’s why I don’t want models that look happy. That model had better be happy.”

If Leon was an institution, then Dwight was definitely a comer. He was born in 1951 in Wilmington, Delaware, had a middle-class upbringing, was president of student government and a state champion in track and cross-country. He got an athletic scholarship to La Salle College in Philadelphia, where he thought he was preparing to be an Episcopal priest. Then Dwight got a chance to design some liturgical vestments, which turned out to be an epiphany for him. He quit running, quit the Church, and enrolled in New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology.

Neiman-Marcus brought Dwight to Dallas, where he and Kim Dawson discovered each other in 1976, shortly after he had made a frustrated departure from Neiman’s executive training program. He started producing specialty shows for Kim, and he is working a lot now—New York, Miami, Dallas. But something about his fashion shows still correlates with the days when he was preparing for the priesthood. “If fashion is a religion,” he says, “then fashion shows are the Eucharist of the business.”

No Communion ever had an audience clapping its hands if it started running behind, however, and Dwight’s show was even later getting under way than Leon’s. Finally Gloria Vanderbilt herself appeared, dressed in her usual high-collared Victorian blouse with her hair slicked behind her ears and flipped up in the back, just the way she looks on television. Gloria’s brief introduction was laced with happy words like “delight,” “excite,” “enjoy,” and “love,” just like her television persona. Then she sat back to see if Dwight Byrd could help her get into the hearts, and hopefully the pocketbooks, of middle America.

Back on the third floor, Leon was introduced by Kim Dawson and began what is surely one of the most extraordinary live performances in the annals of show biz. He walked to the podium at the right of the stage, sat down in a tall chair, propped one leg on the stage, and set a lengthy list on the lectern. But instead of looking at the list, Leon, in a voice as rich and unctuous as a handful of pearls dipped in citronella, began to give, almost entirely from memory, the designer’s name and an ad-libbed description for each of the 280 pieces in the show.

“Directions,” purred Leon as he set up his first scene, “where fashion starts out in its purest form and sort of filters down where we all can enjoy it. . . . Lingerie absolutely too delicious ever to stay at home. . . . The sexy dress, the dress that appears to plunge all the way. . . . The most crushable pant that you’ve ever seen. . . .” The models cruised past every few seconds, then dashed up the side aisles for their changes. The buyers gaped at the staggering onslaught and made little marks on their programs.

Dwight’s show was turning out to be more of a Busby Berkeley production, with a two-story mock-steamboat set, an expertly choreographed dance troupe in sailor tops and shorts, Gloria’s jeans, shorts, and pants in bright Easter egg colors, and things for little kids and big, beautiful women, too. At the end of the show the spotlight came back on Gloria, and a little girl brought her a bouquet of flowers. Everybody loved the show; it was swift, visual, and charming. Gloria made you feel happy. Gloria, however, never did tell Dwight whether she was happy with the production that Murjani had just spent $75,000 of its advertising budget on.

By the time the Murjani show ended, Leon was cruising along like a distance runner in the euphoric interlude between initial lethargy and serious oxygen debt. “Fiesta in Guadalajara. . . . The genius, the magic of Emmanuelle Kahn. . . . White does sort of brighten up and spark up every color that it nears. . . . Neckline—superb; back—not to be believed. . . .” Kim Dawson returned from watching Dwight’s show out on the terrace and began coaching her models under her breath. “Come on off to the left, Carol,” she prompted in a whisper, and when the model turned right, Kim rolled her eyes and smiled.

Leon kidded, he seduced, he editorialized. He made it clear that he didn’t like cowboy chic, but just this once some cowgirl stuff would be okay. He did his obligatory “Qiana excites . . .” and moved into his exotic stretch drive. “They’re back—the bonbon colors.” It was well after seven and Kim began to worry about the length of the show, but Leon was moving rapidly to the extremities of the fashion universe. “Please meet my intergalactic princesses . . . intergalactic princesses who are always used to winning.”

It went on until nearly 7:30, and after that Sheila Davlin hosted a reception with crab claws, champagne, and canapés on a terrace overlooking the Great Hall. Day two was over. Ahead lay the biggest buying days of the market, and by now appetites were surely whetted.

A Model of Ambition

The apparel business is largely commanded by men, but it employs an army of women, and women are the foot soldiers of the Apparel Mart. There are thousands of part-time employees, mostly women, for whom the markets are a steady source of supplementary income—housewives, college students, freelancers in all sorts of fields looking for extra cash, the unemployed, and neophytes hoping to break into the rag business. They sell clothes, manage showrooms, answer phones, serve food, or model clothes, jobs that bring anywhere from $35 to $200 a day.

On Sunday morning Susan Moore had to get up at 5:30, which had put some restrictions on her social life the night before. But her duty was quite clear: do the infamous morning show—Kim’s Spring Market Report was today at 7:15—or somebody else would. And that, of course, was the real motivation: the Kim Dawson Agency may have lots of models, but only Kim’s best models do the market shows. It is a somewhat dubious honor in a business where the minimum respectable wage for photographic work is $65 an hour, because the shows pay only $60 for considerably more than an hour’s work. But there was a tacit understanding that models who worked the shows would get booked elsewhere between markets. So models who wanted a career, not a hobby or a social scene, bucked up and got in there in the morning.

Susan wanted that career. A 22-year-old from Lewisville with long, almost black hair, she had come to modeling from a track scholarship at Texas Woman’s University. A strapping five-foot-nine, 140-pound four-hundred-meter hurdler at the time, she was discovered by a photographer at a track meet during her freshman year. She lost 15 pounds, joined KDA, and slowly started working. She made around $5000 her first year, $10,000 her second year, working as a hostess to keep body and soul together. But now she has finally started modeling steadily, and she hopes to make at least $24,000 this year.

The spring market was just part of the routine. She not only did four shows but she also worked in a designer showroom every day. But she had had to knock down her showroom rate from $100 a day to $80 because she also needed to run out and do shows at Neiman-Marcus on Friday and Monday. There was a possible bonus this weekend, though; she had heard that the Murjani show, which she had been in, might pay New York scale, which is $450 a pop.

Susan, however, wasn’t overcome by being one of the elite in the Apparel Mart women’s infantry; she was hoping for better things. Right now she is taking acting classes at KD Studio (another Kim Dawson enterprise) and voice lessons from a private teacher. “I want to be an actress,” she said, “as in real big time.”

A Business (Sigh), Not an Art

Sunday at one, on the third-floor landing, a sampling of buyer ID badges revealed these home bases: New Zealand; Puerto Rico; Booker, Texas; McAlister, Oklahoma; Fort Smith, Arkansas. On the second floor at the same time, Julainne Jones was taking a break. As editor of Fashion Galleria, a local publication, she was interested in pumping Group III people on possible new fashion directions, but the market was so busy that nobody had time to talk.

Not that she had high hopes of finding anything revolutionary. “I don’t see any commitment to originality from Texas or New York,” she said. “Everybody talks about ‘investment dressing.’ They say, ‘We want flexibility. We want to service our customers.’ ” The problem was that designers always fall back on traditional looks during a recession, because customers will go for classically styled garments that will give many seasons of service and be appropriate for many occasions. “That’s tailoring, not fashion,” said Julainne.

The real revolution was back in 1971, when Yves Saint Laurent shocked the fashion world by announcing that he was mass-producing his new couture line and selling it out of a string of Rive Gauche boutiques. The YSL ready-to-wear line became a fabulous success, and the other Paris designers had to follow suit. The designer ready-to-wear stampede immediately spread west, sparking the dramatic rise of the current generation of big New York lines like Halston and Calvin Klein. “When Yves Saint Laurent went ready-to-wear,” said Julainne, “fashion became a business instead of an art.”

The Fantastic Two Per Cent

Bill Becker and Belva Morrow own the showroom on the third and fourth floors where Rubylee Richardson buys her Halstons. They have, by consensus, one of the classiest operations in Group III, if not the classiest. Bill and Belva are considered to be among the four or five “great powers” in Group III; they have what many people feel is the best selection of luxury lines—Halston, Blassport by Bill Blass, Hannae Mori, Harold Levine, Miss O by Oscar de la Renta, and Rita Angelo, a large-size designer line that manufactures up to size 20—and they have been in the forefront of the push to attract the best designers in the world to the Dallas Apparel Mart. They hold what is currently one of the choicest hunks of real estate in the entire building, rooms 3433 and 4433, smack in the middle of the red-carpet area adjacent to the Fashion Theatre.

Of course, it wasn’t always that way. Bill Becker, a short, irrepressibly enthusiastic man with brushed-back springy-curly hair, was once a St. Louis kid who came to Dallas and went to work for Howard B. Wolf, Inc., a big name among local manufacturers. He spent twenty years there, rose to be president of the Howard Wolf division, and felt trapped. “In a corporate structure,” he said, “you get in a pigeonhole and you can’t get out of it.” The way out, he finally decided in 1975, was in the higher-priced, luxury trade, although at the time he wasn’t really sure that his customers would have a tremendous demand for designer lines.

Petite and deceptively frail looking, with her dark hair pulled straight back, Belva Morrow used to work markets after she graduated from Sunset High School in Dallas. She started with Howard Wolf twelve years ago, had a close working relationship with Bill Becker, and in 1975 went with him into the brave new world of high-priced apparel.

It was not an instant success story. What they had going against them was a poor location. Their showroom—the same one they are in today—was so off the beaten track at the time that most of the surrounding rooms were used by fabric salesmen. “People thought we were insane when we took this space,” remembered Bill. What they had going for them was a loyal contingent of Howard Wolf customers and enough savings to endure a year without making any money. In their first market they did only $33,000 worth of business, but by the end of a year they started seeing black ink.

Then something quite remarkable happened. Bill and Belva started acquiring some big-name lines—“We had to associate ourselves with people who had staying power,” says Bill, “and they just happened to have fantastic designer names”—and they suddenly found that their old Howard Wolf customers, who had previously been intimidated by designer lines, were clamoring for the stuff. The increased output of big-name designer ready-to-wear had made prices less prohibitive, and that price movement coincided with a new sartorial desire among well-to-do women in Everywhere, USA, a desire that could be quenched only by the best designer clothes—and cost be damned. The designer boom had hit, and Bill and Belva were right on top of it. At this market they were looking for at least $800,000 in sales. “We only deal with two per cent of the economy,” said Bill, “but what that two per cent does is fantastic.”

That 2 per cent also demands fantastic service, and by Sunday afternoon Bill and Belva had put a lot of effort into that. For openers, they were spending $60,000 a year in rent just to be where they were. They had also spent $140,000 on remodeling, which went toward the burgundy carpet, the stairwell that led to the second floor, the kitchen and the bar, the dressing rooms for the models, the offices, the three private showrooms, the track lights, the antique-look furnishings, and even the tortoiseshell and silver-metallic show hangers. There were on hand three maids, two women to help with seating, a receptionist to log buyer appointments, and seven salespeople who each handled one line exclusively. In addition, many lines would send principals like Halston vice president Don Friese; on the third floor, in fact, designer Harold Levine was showing his own clothes. The specialization extended even to the models; Lisa, a top Kim Dawson model, had been modeling Halston exclusively for two years.

But service alone isn’t enough to keep a showroom at the pinnacle of the Apparel Mart pyramid, and Bill and Belva spend two to three months a year in New York, scouting for new directions in fashion. The tab runs up at the rate of $400 a day, but Bill and Belva know that the expense is necessary. “The only constant in this business is change,” said Bill. “We don’t know who the next Halston is going to be, but we’re always looking.”

Errol Flynn Gone Punk

That was undoubtedly why Joseph Piselli was showing his new Bal de Grace collection in Bill Becker and Belva Morrow’s showroom. Joseph was, to put it mildly, a little outré by Apparel Mart standards. A young, ruggedly handsome man, he was wearing white leather pants that were full in the thighs and cut very closely at the shoe tops, so that they clung tightly to his grayish-green pointed-toe, high-heeled boots. A length of steel cable formed a sort of tie at the collar of his long-sleeved white cotton blouse, and a very wide snakeskin belt cinched his waist. Two studs—one gold, one diamond—pierced an earlobe, and his dark hair was piled high and greased straight back into an enormous fifties-style pompadour. It was touted as the “pirate look,” a sort of Errol-Flynn-gone-punk synthesis.

But behind the show, Joseph had a lot of go. For one thing, he had credentials. He was a graduate of the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, and he had assisted very-big-name designer Giorgio Sant’Angelo. For another thing, Joseph’s clothes—Bal de Grace was a sophisticated line of sportswear—were terrific. They were actually designed, with great geometric slashes of dramatic but carefully controlled colors that gave the garments a sort of architectural logic and purity. They had just the right mixture of chromatic brilliance and well-conceived color coordination, and the tailoring was severe enough to stand out in a crowd but tasteful enough to make the customer glad she was standing out in a crowd. And finally, Joseph had a very good idea of where he was going with his clothes. Sure, he was just testing the waters here in middle America, but he had an instinct that somebody out there needed him. “You’ve got that young customer who is just starting to spend her money,” said Joseph, “and she doesn’t want to look like mother.” As it turned out, Joseph wasn’t the only one to sense this.

At about 4:15 on Sunday afternoon, Polly Adams, the owner of a very chic dress shop in Laredo, came into Bill and Belva’s to look at Izabel, a line that was being shown off a rack right next to the Bal de Grace rack at the east end of the fourth-floor salon. Polly, who wore her black hair short, was in a beige skirt and black corduroy jacket, and with her was her assistant, a younger, very Latin woman with long dark hair. They asked about a gold leather skirt and checked out some nice-looking white cotton dresses but did not seem overwhelmed.

Then three more people came in and sat down two tables over. The trio consisted of a buxom young woman in black shirt and black pants, with a big Loretta Lynn sweep of hair; a teenage girl in casual pants and a print shirt; and a man in a polka-dot shirt, with huge muttonchops sprouting from beneath the layer of razor-cut hair that capped his head. They were from Hobbs, New Mexico, and they started writing orders on Bal de Grace as if they were stocking up on canned foods to store in a fallout shelter. Belva Morrow, meanwhile, came up and whispered to Polly Adams and her assistant that Joe had worked with Giorgio Sant’Angelo. “Oh . . . well,” said Polly, who had just gone from curious to impressed.

While the Bal de Grace line rep, a short brunette, and Joseph’s model, a tall, thin brunette, showed the line to the Hobbs trio, Joseph just sort of hung back and watched in amazement. Finally Polly’s assistant couldn’t stand it any longer. “Your clothes are fantastic,” she blurted out. With that, a mutual courtship began. The Bal de Grace model, in a little crop top and shorts, came over to the Laredo table. Joseph launched into a brief summary of the line, pulling out jump suits, shorts, pants, and blouses. The Hobbs contingent went on buying. “I wish I could find something I didn’t want,” said the black-garbed woman as she wrote furiously. The other salesmen were now standing around gawking at what was, for a designer showroom, an unusual buying frenzy.

Now Polly and her assistant were ready for a detailed showing of Bal de Grace, and Joseph started back through the line while Polly’s assistant began writing at a steady clip. The ladies looked at Picasso print blouses and pirate blouses, shorts and trousers. They ordered jackets and jump suits, explaining where Laredo was to emphasize the necessity of early spring shipments. Technical problems—like fit, a constant worry in the garment trade—arose and were overcome. “What is your size two blouse like?” queried the ladies.

“Do you carry Perry?” responded Joseph, meaning Perry Ellis.

“No, he’s too heavy,” said the ladies, meaning that Perry’s layered look is too hot for Laredo.

“Well, these are sized like Perry,” said Joseph, looking for some way to make the translation. “It’s not a full missy fit.” Just before five the Hobbs contingent left, sated with ordering.

When the Laredo duo finished buying ten minutes later, they were euphoric. They said they were tired of conservative lines like Calvin Klein that never took any risks, lines that were increasingly tending to look the same. Joseph agreed. “When things get bad,” he said, “everybody goes to the traditional look. All these designers—like Calvin—they just repeat, repeat, repeat.”

When all the buyers had left, Belva excitedly came over to Joseph. Everyone was particularly amazed by the Hobbs crowd. “When I saw the sideburns,” Joseph told Belva, “I thought, ‘No way.’ ”

“That will teach you,” said Belva briskly, “never to prejudge.”

At six in the Great Hall, Kim Dawson presented the 1980 Dallas Flying Colors Awards, yet another fashion show. Dwight Byrd produced it, and one of the touches was a model in lingerie who walked down the runway carrying a basket, which she opened to release dozens of live butterflies. With that, day three ended.

From Paris to Conroe With Love

When Rubylee Richardson had finished buying the Halston line on Monday morning, Don Friese and a gaggle of showroom personnel escorted her to the door. Friese wanted to know if she was interested in the Halston IV sportswear line. “I can’t sell that,” said Rubylee as flatly as a surgeon discussing an inoperable tumor. “You know best,” said Friese without protest, and then he bid her a very courteous farewell.

Rubylee had indeed learned a lot in her ten years in the business. She had been past forty, a secretary for an advertising company, when she first decided to realize a long-standing ambition. “It’s every woman’s dream to own a dress shop,” she said. She found a banker who also believed, and she opened a specialty shop in a new shopping center off IH 45 near Conroe. It was a tiny store, and for a while she was just getting by. But things picked up when northern Houston began to get in on the designer movement, and nearby communities like Spring and The Woodlands, a planned suburban utopia, began to mushroom. Rubylee’s moved to larger quarters in Oak Ridge Plaza Center and today has two thousand square feet of floor space and does $200,000 in sales a year. It is hardly an empire, but it is undeniably a mecca for local women of fashion.

Rubylee had come to market with a $65,000 open-to-buy budget, and on 90 per cent of her orders she would leave her paper in the showroom when she left. What that meant was that she would, on the basis of what she saw in the showrooms during her four days at market, make on-the-spot commitments to more than $100,000 worth of spring inventory. Other buyers might take their paper with them—which meant that instead of leaving their orders in the showroom they would take them home and ruminate over them—but Rubylee didn’t work that way. She knew her customers, colors, sizes, lines, and prices, and she could cross-reference this data in her head with computer precision. But when it got down to it, the buying was all instinct. “If you have to stop and think about it,” she said, “you’re dead.”

After she left Bill and Belva’s, Rubylee stopped at the Designer Showcase on the fourth-floor mezzanine to check out Fabio Delini, a new Parisian line making its Apparel Mart debut. Beth Wildstein, the line rep, had sold Bill Haire and Bill Atkinson, both name New York designers, to Rubylee for four years, and Rubylee had come to respect Beth’s judgment.

The Fabio Delini people had approached Beth while she was repping Bill Atkinson. Fabio Delini wasn’t a designer but a design group corporately owned by Najer International, which also owns the popular Serge Nancel line. Beth had the opportunity to get in as a line owner, which meant that she had a piece of the action, a place in the design group, and the obligation to find some customers for the new line. And because Rubylee trusted her, Beth was in a position to form a synapse of taste between Paris and Conroe.

Beth made the usual dry run through the line. The skirts, pants, and blouses were mainly bright abstract prints in cotton and silk, very elegantly and artistically done, with, as they say in the trade, excellent detailing. But Rubylee did not register approval, except when she was shown a $65 solid white crepe de chine jacket. Beth, meanwhile, made no attempt to hard-sell the line. In showing a skirt and jacket ensemble in white and olive, she had a word of caution concerning other color options on the same outfit. “This is the only way to do it,” she said. “The other two colors are awful.”

When Beth had finished, Rubylee took a few seconds to form her response. “I’m not totally overwhelmed,” she said candidly, “but this is new and different. I’m going to have to think about it.” Rubylee explained that she needed good prints, especially blouses, because the market was flooded with solids. But buying prints was a tricky business; solids definitely made safer merchandise.

Having discussed her apprehensions, Rubylee immediately set them aside. “Let’s go to work,” she said, and promptly bought the first outfit shown, a three-piece ensemble at $212 wholesale. As Beth moved through the line Rubylee consulted dozens of fabric swatches and gave her views on colors, sizes, and clientele. When she signed the order form fifteen minutes later, she had knocked another $2000 off her open-to-buy.

Rubylee’s next stop was in Group II on four, the upstairs annex of Group III. Betty Hanson, another name New York line, was Rubylee’s target here. She hadn’t made an appointment, but Steve Skoda, the line rep, was only too happy to show her his merchandise right away. Rubylee sat down in a chrome and leather director’s chair next to a table holding a big bouquet of orchids.

Steve moved very quickly through the line—neutral-colored knit skirts, pants, and jackets combined with striped blouses in soft pastel colors. Rubylee ordered very quickly. A striped jacket with culottes and slacks in petal-pink and lilac. A cream blouse with a three-color abstract appliqué on the front. “I think it looks just like Sylvie Browne,” said Rubylee.

With most of the buying done, Rubylee discussed the merits of fibranne, an expensive-looking rayon fabric now popular in many high-priced lines. “Our customers need more education about rayon,” she said. “It’s not what people think it is.” Rubylee also quizzed Steve on Betty Hanson’s advertising program, which turned out to be an extensive print, TV, and cable TV schedule. Rubylee was particularly interested in cable TV, since she had already put Bill Haire and Halston promotional programs on The Woodlands’ cable network. Then she wrapped things up with a quick preview of some tank tops and split skirts for summer. When Rubylee had finished she had written $5000 in orders.

It was 11:30 on Monday morning. In two hours Rubylee had spent over 10,000 of an independent businesswoman’s hard-earned dollars. If her instincts were right, that $10,000 would jump right back in her pockets this spring, along with a good profit. But if her intuition was awry, then she had just thrown that money away.

The Televisions Vanish

Late Monday afternoon a change came over the buyers. It was as if they were in a film that had suddenly been switched to a slower speed, with the volume turned down, or as if they were approaching the borders of narcolepsy. In the showrooms every line rep and line owner who was anybody in New York seemed to be getting ready to leave; they had acquired valuable forecasts about the performance of their lines when the New York market opened in three days’ time. Most showroom models celebrated their last day of work, and the showroom owners realized that the serious business of this market was over.

On Tuesday morning the loading dock at the rear of the building began to fill up with racks of clothes. In the showrooms scattered customers were still being shown the lines, but there was a morning-after pall to business. The models in the daring swimsuits who had attracted attention in the flashier junior showrooms seemed, now that there were no crowds to gawk at them, strangely undressed.

By Tuesday afternoon sales managers and showroom owners were pounding the calculators in their offices; the consensus was that it had been a very good, very encouraging market after a slow year. A fleet of cabs waited in front of the building; every buyer, rep, model, and other temporary denizen who hadn’t already left was getting ready to.

On Wednesday, the last official day of the market, one buyer sat alone in the Great Hall, watching a giant video screen from which a huge blonde model was purring, “I beg your Chardón.” A porter wheeled a live tree down a third-floor hallway. Maurice Taub said his market had been “only fair.” Kim Dawson saw the market as “a turning point for the economy.” Four bored-looking, fashionably dressed young Japanese men stared at the video screens in the entrance lobby; the screens were now blank.

By Thursday morning, even the TV sets were gone.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fashion

- Dallas