Not long after Steve Winn purchased a 1,400-acre property in the Hill Country, his new next-door neighbor Lew Adams took him on a tour. Adams, a 78-year-old environmentalist, is a fierce custodian of a Central Texas treasure you’ve probably never heard of—and for good reason. Since his parents purchased this land in Roy Creek Canyon, in the forties, the family has gone to great lengths to keep the nature reserve, located thirty miles west of Central Austin, a secret to all but a select few. Those lucky enough to descend into the lush, two-hundred-foot-deep gorge, following a rugged path that snakes through jagged limestone boulders and native flora sprinkled with wild turkey feathers, have done so only by invitation from the Adams family. The reason for this rigorous gatekeeping becomes clear to visitors when they reach the bottom and see a crystalline pool of spring-fed water—usually seventeen feet deep and cold to the touch, even in summer—shimmering beneath a dense canopy of centuries-old cypresses that block the outside world from view.

On this particular spring day, in 2019, Winn (not to be confused with the Las Vegas developer Steve Wynn) and his wife, Melinda, were the guests of honor. Looking awestruck as he stood beneath the towering trees, Winn, who made his fortune in technology and real estate, surprised Adams by comparing the landscape to a cathedral. When the two men parted ways later that day, Adams was hopeful that Winn’s immersion in the space had opened his eyes to the importance of protecting the land he’d bought next door and the springs around it.

Home to a newly discovered species of salamander, a rare species of freshwater arthropod, and hundreds of plant species, Roy Creek Canyon serves as one of the best remaining examples of the biodiversity that once reigned across Central Texas. If the arrowheads littering the area are any indication, the springs were frequented by Indigenous peoples for hundreds of years. But for the past eight decades, swims in the creek’s pristine waters have been reserved for the Adams family and its network of close friends, whose ranks have included birdwatchers, naturalists, and a who’s who of left-leaning Texas writers and politicians.

On a warm summer evening some decades ago, a visitor to Roy Creek might have encountered Governor Ann Richards and the journalist Molly Ivins holding court on a boulder beside the water. “Molly would come up here and tell some of the raunchiest jokes you’ve ever heard in your life,” Adams recalls. “And Ann could tell some too!” Like anyone else who used the site as a respite and a retreat, both women did so with the understanding that it should remain concealed from public view — and that they would be responsible for any dishes they dirtied inside the family’s tiny cabin overlooking the swimming hole.

“My mom and dad kept this place so quiet because they didn’t want people to change it,” Adams told me last October while we sat at a picnic table near the creek. “It’s both good and bad. Roy Creek has been protected, but if they’d brought more people into the fold, there would be thousands of people screaming about what’s happening right now.”

What’s happening is that in the coming months, the rolling hills of dense cedar and grassland that almost entirely surround Roy Creek Canyon will be developed into Mirasol Springs, a luxury resort and housing development financed by Winn’s company that could radically transform this largely untouched land.

Like most battles about a relatively small piece of property, the fight over Roy Creek is part of a much larger struggle.

On one side are the Lew Adamses of the world: environmental purists committed to the notion that the most beautiful and biodiverse parts of the Texas Hill Country should not only remain undeveloped but habitats should be restored to the shape they were in before heavy land use whenever possible. On the other side are developers, who are taking advantage of booming population growth in and around Austin and San Antonio—as well as the fact that only about 5 percent of the region has been set aside for conservation—to bulldoze some of the Hill Country.

Mirasol Springs is pitching itself as a third option, a model for sustainable growth. “Advocates for conservation and development should be able to coexist and embrace important elements of each side,” Jim Truitt, the director of real estate at Mirasol Capital, the Dallas-based investment firm behind the project, told me during a recent tour of the site. “Regional development is coming, and it needs to be cooperative.”

Though the final plans are still being amended, Mirasol Springs is set to include a seventy-room hotel, 39 residential lots, and another thirty cottages managed by the hotel. Guests will have access to a spa, walking trails, an organic farm, and the nearby Pedernales River for fishing, canoeing, and kayaking.

Compared with that of other Hill Country resorts, the proposed capacity is modest. The Omni Barton Creek Resort & Spa, for instance, about ten miles west of downtown Austin, sits on four thousand acres and has about five hundred rooms. Even more unusual, more than two thirds of Mirasol Springs—around one thousand acres in total—will be turned into a conservation easement, a move that guarantees that this portion of Winn’s land will remain undeveloped for generations to come. The site also will include a University of Texas–run field station that will be used for conducting biodiversity research. “Mirasol Springs will successfully demonstrate a new standard for Hill Country design that embraces land stewardship, eco-sensitive design and development, restoration and education,” Winn told me via email. “The project is a unique opportunity to create a living, learning and laboratory environment unlike anything in our state, creating a new standard for development and research education.”

Still, Adams is convinced that it’s only a matter of time before Roy Creek Canyon is severely damaged by Mirasol Springs. He and some other locals believe the project represents a philosophical shift in a part of Central Texas that boasts a high density of conservation easements—which preserve sensitive natural areas and limit building—in the state. That’s partly because of an extraordinary grouping of natural wonders within a few miles of one another, such as Hamilton Pool, Westcave Outdoor Discovery Center, and Roy Creek Canyon. The area is exceptionally fragile, even more so because the Trinity Aquifer, from which Mirasol plans to draw water, is already in decline and the Pedernales River, which the resort would also rely on for water, stopped flowing amid extreme drought conditions this summer and last.

“The alarms went off when people in this area first heard about Mirasol Springs,” said Christy Muse, cofounder and former executive director of the Hill Country Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting Hill Country habitats. “To their credit, the Mirasol people paused and wanted to hear what locals had to say. They thought they were doing something really great right off the bat and quickly learned that a lot of people around here don’t feel the same way.”

Developers held numerous meetings with local residents and faced a slew of media attention in 2022. Ultimately, they reduced the number of homes they planned to build, barred residents from digging wells, and added even more land to the property’s original conservation easement, ensuring that the vast majority of Mirasol’s land will never be built upon.

For Adams and others, though, the entire process has been troubling. As they’ve learned, when landowners such as Mirasol decide to develop their property, there’s little neighbors can do to stop them.

In recent years the drought in Central Texas, combined with the explosive development brought on by the growth of Austin and San Antonio, has caused water levels to plummet in parts of the Trinity Aquifer, a ribbon of limestone that runs from south-central Texas north to Oklahoma and provides much of the drinking water for the Hill Country. Experts agree that the “dry line,” long known as the “100th meridian,” the major boundary separating the more humid Eastern United States with the dryer lands to the west, is edging eastward. Over the past century, it has shifted 140 miles, and now runs about thirty miles east of Austin, leaving all of the Hill Country on the dry side. The region has endured severe drought conditions before. Between 1949 and 1957, rainwater across all of Texas dropped by half and temperatures rose, unleashing some of the driest years on record. At the time, around 800,000 residents lived in the Hill Country, including in the capital city. Today, nearly three million live there, and that number is rising rapidly, with Austin ranked as one of the fastest-growing cities in the country.

This summer the beloved swimming hole Jacob’s Well stopped flowing for only the sixth time in recorded history. Last summer, in New Braunfels, Comal Springs, whose water comes from the Edwards Aquifer, also ceased flowing, as did portions of the Llano and Pedernales Rivers (the Pedernales reached zero flow again this summer), which stopped feeding water into the Highland Lakes that Austinites rely on for drinking water.

There’s a strong chance that Central Texas springs will become a relic of the past, according to Doug Wierman, a hydrogeologist and a fellow at Texas State University’s Meadows Center for Water and the Environment who has served on the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation Board. “As development moves west from the I-35 corridor, one by one we are losing these iconic preserves,” Wierman said, comparing the growth to a steamroller moving west. “Roy Creek is not necessarily unique on its face. There are a lot of these springs tucked away in the Hill Country, but as land is partitioned, developments added, and more groundwater pumped, they’re disappearing.” When asked what could be done to stop springs from being destroyed, Wierman, who has studied Roy Creek and thinks it could face the same fate as Jacob’s Well, offers a simple answer: “Don’t pump the shallow groundwater that feeds the springs.”

Though Wierman is confident that even minimal pumping will lead to Roy Creek’s demise, Mirasol developers argue that there’s enough groundwater for the project to use during periods of drought without impacting local springs. They say that less than 5 percent of the development will include impervious cover, which keeps rainfall from being absorbed into the ground. “Unlike some developments, we’re not trying to see how many homes we can squeeze onto this property,” said one Mirasol planner.

To help offset the use of precious groundwater, Mirasol plans to use reclaimed wastewater and harvested rainwater. “Every rooftop on the entire property will be required to collect rainwater,” Truitt said, noting that deed restrictions will prohibit herbicides and pesticides, nonnative plants, and septic systems and private wells. “The goal is to redefine what responsible development across the Hill Country can look like.”

In order to preserve the groundwater that feeds the creek’s springs, the development has acquired a Lower Colorado River Authority contract that allows for pumping surface water from the nearby Pedernales River—the same one that stopped flowing this summer and last. Truitt said it would operate groundwater pumps only if the LCRA curtails its original contract, at which point the development, as a utility district, would be required by state law to provide guests and residents with a consistent and reliable water source. At no point, developers say, will groundwater be used for landscape irrigation.

There’s no easy way to quantify how much water Mirasol will use once the resort opens to the public. Though developers expect to use less, Mirasol’s contract with the LCRA allows it to pump around 100,000 gallons of water from the Pedernales each day, except under certain drought conditions. Based on water availability studies, the developers estimate the contract will provide about 80 percent of the project’s water. They say the region’s aquifer holds enough to supply the other 20 percent.

But there is little doubt that the Highland Lakes, which store water supply for more than two million Central Texans, are nearing a crisis point as long-term drought and lowered lake levels become a permanent reality of life in Central Texas. Already, some climatologists are predicting that conditions in Texas suggest that the state, like California before it, could be hit by a megadrought lasting for decades by the end of the century. These fears have prompted some experts to begin calling for the LCRA to begin implementing more conservation efforts. Because Central Texas continues to experience severe drought conditions, the LCRA has implemented the first stage of a drought contingency plan that asks customers to voluntarily reduce their water use. The region’s two largest lakes —Lake Travis and Lake Buchanan —are already at less than 50 percent capacity. Should the levels drop another 10 percent or so, to 900,000 acre-feet, the LCRA plans to implement “mandatory water use reduction measures” among customers with contracts including Mirasol. “With very little water flowing into the lakes and a ‘heat dome’ roasting our area since early June, lake levels are decreasing as significant amounts of water evaporate or are used on landscaping in the region,” John Hofmann, LCRA executive vice president of Water, said in a July news release urging regional conservation due to declining lake levels.

If the LCRA were to curtail its contract, Truitt said, the site also plans to build storage tanks that will fill up when water is plentiful. Storage tanks won’t last forever, but the developers are confident their water supply system will be sufficient to meet demand. Truitt notes that developers have a shared interest in ensuring that the creek continues to flow. Had someone else purchased the land Mirasol is building on, things could be worse. Another developer could have packed the site with homes without setting aside land for conservation.

That offers little comfort to Adams, who said, “What Mirasol is currently proposing is sort of like the canyon dying a slow death as opposed to a fast one.”

This was, to say the least, disappointing to Adams, who thought he had swayed Winn to his side when he had given him that tour back in 2019. Two years later, when Adams had a chance to ask Winn why he’d decided to turn that same land into a development, the businessman, he said, sounded more like a hard-nosed investor than someone committed to conservation. “He said, ‘Lew, anytime I invest in something I need to see a ten percent return on my investment,’ ” Adams recalled. Today he wonders whether Winn’s “cathedral” comment was part of an elaborate ruse.

He’s particularly rankled about the field station that UT will be operating. Adams said that before Winn bought the land, he pitched to school officials the idea of turning Roy Creek Canyon into a university-managed property dedicated to research and education. Their enthusiasm for this idea is documented in correspondence that Adams provided to Texas Monthly. But Adams said the project never materialized, and in the meantime plans for the field station on the Mirasol property were proposed and approved.

The UT officials Adams had been speaking to declined interview requests, and a UT spokesperson declined to say how the partnership with Mirasol emerged and how much money Winn had donated to the school. A budget proposal created by UT in 2020 and later acquired by Texas Monthly shows that the university sought more than $64 million in gifts from the Winn family that ranged from a $7 million field station to tens of millions of dollars for a variety of endowments connected to the College of Natural Sciences. The university is “thrilled to partner with the Winn Family Foundation” on the field station, the spokesperson said. “This research by our faculty and students relates directly to conservation and protecting land and water resources in the Hill Country.”

Adams said he managed to convince one former university administrator to meet with him last year at an airport hangar in Llano. According to Adams’s account, the former official from the College of Natural Sciences told Adams that he’d been forced by the school to sign a non-disclosure agreement about the university’s partnership with Mirasol. “He wasn’t proud of it, but he found a way to rationalize his decision,” Adams said. “He said, ‘Well, do you want UT to just drop out and not be a part of this development at all, even if it’s problematic for the environment?’ I said, ‘Well, I think they’re just using you all’ and he said, ‘Wouldn’t you rather have us as a voice at the table than have scientists have no say at all?’ The university declined to comment on Adams’ allegations about UT employees being pressured to sign NDAs.

Adams believes that the field station represents greenwashing, meaning cashing in on consumers’ interest in environmentally conscious products by making cosmetic adjustments. To service much of Mirasol Springs, he notes, the developers will need to build electric and water lines and roads, along with miles of sewage pipes that will run over the property. Relatively untouched land will soon be home to pedestrians and limited vehicular traffic, along with any runoff created by their presence and by construction. The developers said they will have extensive runoff prevention measures in place, and they have water monitoring systems in the creek. Guests won’t be allowed on his family’s property, but Adams still worries about hikers venturing into the canyon, destroying habitats and leaving refuse. “You’re talking about tens of thousands of people visiting Mirasol each year,” Adams said. “How are you going to possibly keep an eye on that many people?”

Adams isn’t only worried about the human traffic. He noted that, at one point, Mirasol had constructed a large dog kennel that could hold several dozen dogs, as well as an aviary where the Winn stores hundreds of farm-raised game birds that he and his guests shoot for sport. Adams is concerned the animal waste generated by both facilities could already have impacted Roy Creek, especially during heavy rains. “I’ve been told by experts that bird poop is so nitrogen-charged it is worse than anything if it gets in the groundwater,” he said. “I have no idea where all that is going and it’s really scary for us.”

In recent months, Muse, the co-founder of the Hill Country Alliance, has found herself in conversation with both sides of the dispute, always in search of compromises that will protect as much of the land as possible before construction begins this year. In normal times, she said, Mirasol — with its decisions to conserve water, negotiate with stakeholders, and implement a large conservation easement — would be considered a model development for the region. But as the resort moves closer to construction, Muse said she’s haunted by the reality that, when the current drought and a changing climate are factored in, the development raises more questions than answers. “There is a lot about this that I personally like, but the site they chose is just so fragile that it makes things really challenging and not just for Roy Creek,” she said. “The conservation community in this area is deploying every strategy we can think of to benefit water recharge and the flow in the Pedernales, and pulling water out of the river that makes up 25 percent of the flow into Lake Travis just doesn’t seem logical.”

In 1990 Austinites packed city hall on the day that council members voted on whether to allow a developer and oilman named James “Jim Bob” Moffett to build thousands of homes, multiple golf courses, and millions of square feet of shopping and office space atop the watershed that feeds the legendary swimming hole at Barton Springs. Outside, locals bearing signs packed the sidewalk. For hours, a seemingly endless stream of local speakers approached the lectern to rail against the proposed development. Some read poetry and sang, while others cited legal texts or found novel ways to profess their spiritual connection to Barton Springs, turning the meeting into a communal “love-in” straight out of the sixties, as this magazine’s Paul Burka wrote at the time.

In the wake of his defeat, an angry Moffett (who died in 2021) told Texas Monthly that, because of what he regarded as Austin’s radical conservationist impulses, Fortune 500 companies would never consider investing in the hippie haven. Three decades later, in the age of Instagram, the allure of Barton Springs has played an integral role in making Austin the fastest-growing city in the country, attracting large outposts of companies including Apple, Charles Schwab, Google, Oracle, and Tesla.

Somewhere in the crowd that day stood Adams’s parents, Red and Marjorie Adams. If his mother took a turn at the lectern (and Adams thinks she did), the council members would’ve likely known her by name. For years her weekly birding and conservation column, “Bird World,” had run in the Austin American-Statesman, among other Texas newspapers, giving her a forum to remind readers what was being lost as the region tilted toward a growth-first mentality. “I can remember the things that ‘used to be’ such as a Shoal Creek that had clear pools deep enough for kids to swim in, but which today is only a drainage ditch,” she wrote in 1993. “I can remember when Pease Park had enough natural areas left that roadrunners nested there . . . its wild plum thickets gave replenishment and shelter to migrating warblers.”

The night Moffett was defeated, Adams believes his parents were convinced they’d prevailed in a historic struggle for Austin’s soul. Three decades later, he said, it’s clear they hadn’t won a war, just an early battle. Adams can’t help but shudder when he thinks about what his mother and father would say if they knew a luxury resort was being built on the edge of the land they devoted their lives to protecting — a place whose architecture offers visitors a window into a Texas past that has been mostly reduced to mythology.

“Here we are fighting the same battle over another threatened Hill Country jewel,” Adams said, shaking his head. “Maybe if we’d publicized Roy Creek like Barton Springs, there’d be more people rushing to save it.”

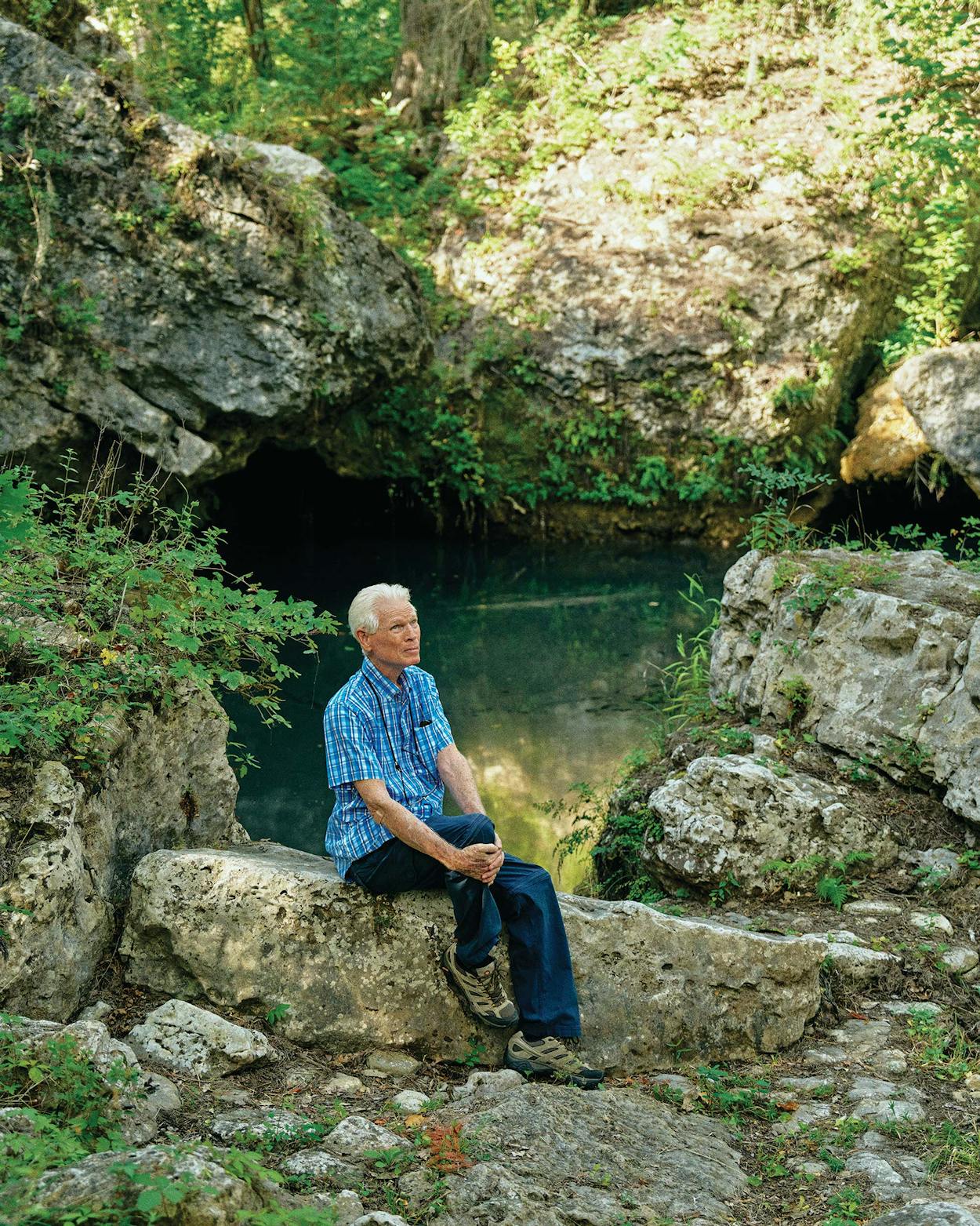

As a boy, Adams treated Roy Creek Canyon like a second home. Now closing in on eighty, his bright red hair turned solid white, he cautiously descends the steep path into his beloved canyon with reverence for a land worth fighting for.

Update: A previous version of this article stated that Steve Winn, the CEO of Mirasol Capital, declined to be interviewed for this story. Due to publishing constraints, Texas Monthly was unable to interview Mr. Winn, but he did offer the magazine a statement via email at the time. That statement has been added to the latest version of this story to more accurately reflect his participation in the reporting process.

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Not in My Backcountry.” Subscribe today.