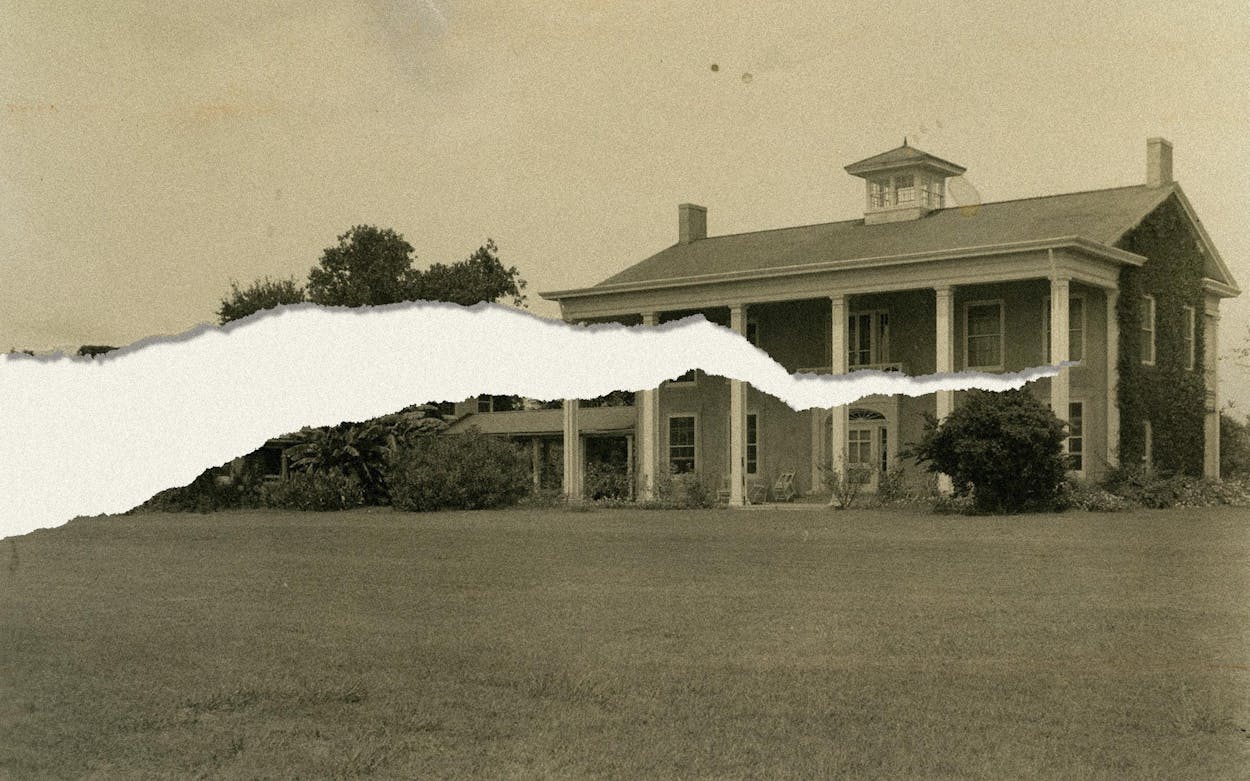

After visiting the Varner-Hogg plantation an hour south of Houston, amateur historian Michelle Haas seemed incensed by what she had seen. At an exhibit that details the farm’s use as a sugar plantation worked by at least 66 slaves in the early nineteenth century, she’d watched an informational video. To her mind, it focused too much on slavery at the site and not enough on the Hogg family, which had turned its former home into a museum celebrating Texas history. She’d also seen books in the visitor center gift shop written by Carol Anderson and Ibram X. Kendi, two Black academic historians who have been outspoken on the issue of systemic racism. Haas denies having been angered but emailed criticisms to David Gravelle, a board member of the Texas Historical Commission, the agency that oversees historical sites at the direction of leaders appointed by Governor Greg Abbott. “What a s—show is this video,” Haas wrote on September 2, 2022. “Add to that the fact that the activist staff member doing the buying for the gift shop thinks Ibram X. Kendi and White Rage have a place at a historic site.”

Over the next eight months, Haas continued to email Gravelle, advocating for such books to be removed. In turn, Gravelle, a marketing executive based in Dallas, took up the cause internally at the Historical Commission, calling on agency staff to do away with the titles Haas didn’t think belonged at the gift shops. As of November of this year, the Texas Historical Commission no longer sells White Rage by Anderson or Stamped From the Beginning by Kendi, or 23 other works to which Haas later objected, at two former slave plantations in Brazoria County, including Varner-Hogg. Among the literature no longer available for purchase is an autobiography of a slave girl, a book of Texas slave narratives, the celebrated novel Roots by Alex Haley, and the National Book Award–winning Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison.

The Texas Historical Commission declined to provide Texas Monthly with a list of titles no longer for sale. Chris Florance, a spokesperson for the agency, said many books were removed from the historical sites as part of an effort that he said was launched in March to reduce inventory as the agency transitions to a new point-of-sale software system. Emails acquired by Texas Monthly through an open-records request reveal, however, that Gravelle was concerned about the way those books presented Texas history and about potential attention from state lawmakers over what books were available for purchase. The emails also show that he had raised those concerns in February, before the agency decided to change its software system.

Haas, a Corpus Christi native, has spent years critiquing historical narratives about slavery. In 2006 she cofounded Copano Bay Press, an independent publishing house specializing in firsthand accounts of Texas history. She wrote and published 200 Years a Fraud, a full annotation of Solomon Northup’s 1853 memoir Twelve Years a Slave, which was made into an Oscar-winning film in 2013. In her book, Haas disputes Northup’s account of his life and argues that many U.S. histories are overly harsh to the South and do not acknowledge that slavery was “a socially acceptable and economically worthwhile practice worldwide at the time our thirteen colonies arose.”

In 2022, Haas launched the Texas History Trust, a nonprofit advocacy organization that aims to fight back against what it describes as “historical societies, university history departments and authors who warp Texas history based on feelings, not the historical record.” She has protested the inclusion of so-called “woke ideology,” “neo-Marxist” influence, and critical race theory in Texas schools, even though CRT—a framework for examining systemic racism, for example in lending patterns—is not taught below the college level in the Lone Star State.

Haas says that Gravelle, who declined multiple requests from Texas Monthly for an interview, was familiar with her before her September 2022 email about the Varner-Hogg plantation. According to Haas, Gravelle is listed on the Texas History Trust’s mailing list and has purchased books from Copano Bay Press. “We don’t go yachting together or anything,” Haas said. “[But] he’s someone who’s friendly to us.”

In the first week of February, a few months after Haas reached out, Gravelle emailed three of the commission’s board members, including the chairman, and two high-ranking staff members, citing concerns “about some of the books (and perhaps other items) and the interpretation at our sites that are not about accurate Texas history, but seem to wander off into present social issues.” Gravelle wrote that he was inquiring because he’d seen a video that questioned the sale of certain books at historical sites, an apparent reference to a recording produced by Haas and posted on the Texas History Trust’s YouTube channel in December 2022.

Gravelle made clear in emails that he feared reprisal from members of the Legislature based on which books were for sale. “I believe we need to take immediate steps to learn the extent of this problem and articulate a remedy, including the source of how this material was approved,” Gravelle wrote in the February email. “There is a good chance it will end up in the open forum of the Lege,” he wrote, adding that he was concerned about “the inevitable press that would be generated due [to] the emotional nature of this national argument if we do not address it quickly. And I mean quickly.”

Matters were not resolved speedily enough for Haas, however. In mid-April, she sent an email to multiple staff members, which she requested be passed on to the board of commissioners and John Nau III, the chairman of the Texas Historical Commission. She then forwarded the communiqué directly to Gravelle. Haas reiterated her concerns about the informational video she’d seen at the Varner-Hogg plantation, and included a list of 23 books that were available at the nearby Levi Jordan historical plantation. “I attach a list of the books available with the publisher’s description of each,” Haas wrote. “You may assess for yourselves how relevant they are to the history of Brazoria County.”

Haas later told Texas Monthly she felt some of the books were inappropriate. “I’m a history person, not a modern theory person. To me, scholarly works on Texas slavery and the voices of the enslaved will always matter more than what Ibram X. Kendi has to say.” Of the titles in the list she sent, seven were historical books that are about or feature sections on slavery and white supremacy—three of which touch on slavery in Texas, specifically—and two are historical novels on the same subjects. Most of the 23 books Haas listed were written by Black authors.

Haas also criticized the Varner-Hogg museum for not focusing enough on slaves who had perpetrated violence against each other at the behest of their enslavers. “Several of the static exhibits at Varner detail the torture inflicted upon the enslaved people who labored there but omit the fact that the chief torturer was one of the slaves,” Haas wrote.

On May 3, Gravelle forwarded the list of books to the board member who leads the historic sites committee, John Crain, president and CEO of the Summerlee Foundation, an animal-welfare nonprofit in Dallas. Gravelle wrote that “there is no question these books are not about Texas history.” That description wasn’t accurate: one of the 23 titles on the list, for example, was Remembering the Days of Sorrow, which features testimony from numerous Texan slaves.

Gravelle then sought to craft a seemingly neutral policy to remove the specific books to which Haas objected. “Honestly, it is not hard to fix,” Gravelle wrote to Crain. “Create a policy which focuses on [how] the only books/gifts subjects that can be placed in a site should be about Texas history. Put the non-historical books in a box and remove them. Waiting on the bureaucracy to move isn’t good enough. The visitor who visits a gift store today will get an impression from the books. Is it the one we want them to have?” Gravelle concluded, “As Committee Chair, maybe you can help.”

Crain, an Abbott campaign donor who was appointed by the governor to the commission, did not respond directly to Gravelle via email. But he noted in an email related to Texas Monthly’s record request that typically he handles inquiries such as Gravelle’s in person. “As a general practice, I bring these issue[s] to the Chairman. Normally, this is shared informally at meetings.” Nau, the chairman, is also a two-term Abbott appointee who has donated more than $1.8 million to Abbott’s campaigns since 2015. Neither Crain nor Nau responded to multiple requests for interviews.

Gravelle also shared his concerns about books with commissioner Donna Bahorich, a former State Board of Education member and former campaign manager for Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick. Bahorich also declined multiple requests from Texas Monthly for an interview.

By the end of May, Gravelle’s recommendation to remove books became a policy. The commission staff created an inventory reduction plan, outlining proposals to halt all purchasing for Texas Historical Commission stores, sell merchandise at a markdown, and identify stock for removal. The deputy executive director of historic sites, Joseph Bell, sent an email to Gravelle confirming that “non-Texas-history books” had been removed as part of a broader inventory reduction effort, per Gravelle’s request.

According to an internal Texas Historical Commission spreadsheet, the two plantation sites had 87 titles available for sale as of June 12. As of November 22, that number had dropped to 39, and all 23 works on Haas’s list, as well as White Rage and one Kendi book, Stamped From the Beginning, were no longer available for purchase at either plantation site. Whether the books were removed and donated, destroyed, or simply sold and never restocked, is unclear. Florance did not respond to questions about what titles were removed and what became of them.

Haas took credit for the removal of the books in an email to supporters of the Texas History Trust. “Hey….remember those politically charged books being sold to the public at state-run history sites?” Haas wrote. “Those are gone now. We worked hard to make that happen.” In an interview with Texas Monthly, however, she couldn’t name the exact titles that had been removed from the sites. The video at the Varner-Hogg plantation that she criticized can still be viewed at the visitor center, at least for now.

When asked if the removal of books could have unintended consequences, Haas said, “There’s always the possibility of overreach or scorched earth. What I wouldn’t want is for someone to say, ‘let’s just print that list out and take it over there and go pull those books.’ What I wanted was for them to evaluate each of these titles on their merit for inclusion at state-run history sites.”

After the publication of this story, Haas said she opposed the Historical Commission’s removal of some of the books. “Slavery is the most historically significant part of the history of those sites. Hell no, I didn’t want the removal of books on the subject.” She cited Remembering the Days of Sorrow, specifically. “If THC, under its new retail policy, has decided not to sell, for example, the WPA slave narratives, I will rally for the return of that title.”

Haas proposed to Texas Monthly, though not in her emails to the Historical Commission, that plantation gift shops could stock other books in place of those removed. She said there are “adequate replacements for something like Roots that that are maybe closer to home,” specifically suggesting The Color of Lightning, a historical-fiction book loosely based on the life of Britt Johnson, about a former slave who moves from Kentucky to Texas and sees his family attacked by native tribes that are hostile to settlers. “Do I say it should be included because he prospered after [being enslaved]?” Haas said. “No, but it is a historical fiction account of this figure that would be good to include.”

That culturally significant books about slavery were apparently made casualties of the culture war deeply concerns historians such as Michael Phillips. He is writing a book on eugenics in Texas, was recently a senior fellow at Southern Methodist University, and filed an initial records request regarding the commission’s efforts to remove the works from gift shops. “We have an appalling situation,” Phillips said. “The idea that these books are irrelevant somehow is really striking.” He added, “to eliminate books about racism at slave plantation sites is like doing an Auschwitz tour and never mentioning antisemitism.”

Out of the 39 books currently available across the two Brazoria County plantation sites, only a handful focus on issues of racism and white supremacy. Visitors won’t find Roots, but they can buy several books that one would not expect to see, following Gravelle’s policy of excluding “non-Texas-history books.” They include a guide to birds in the state, a book of wildlife photo portraits, and a southern cookbook.

Correction, December 12, 2023: A prior version of this story reported Michelle Haas emailed a list of books that she objected to that were available for purchase at the Levi Jordan historical plantation to Texas Historical Commission Chairman John Nau III. She addressed the email to him and other commissioners, but did not include him as a direct recipient.

Update, December 12, 2023: This story has been updated to clarify Haas’s employment and to include more context on the 23 books she emailed the commission about, her thinking on why they might be inappropriate, and her suggestions for replacement titles that could be sold.

Joelle DiPaolo contributed reporting to this story.

Photo Credits: Varner-Hogg: ART Collection/Alamy; Paper: MirageC/Getty

- More About:

- Politics & Policy