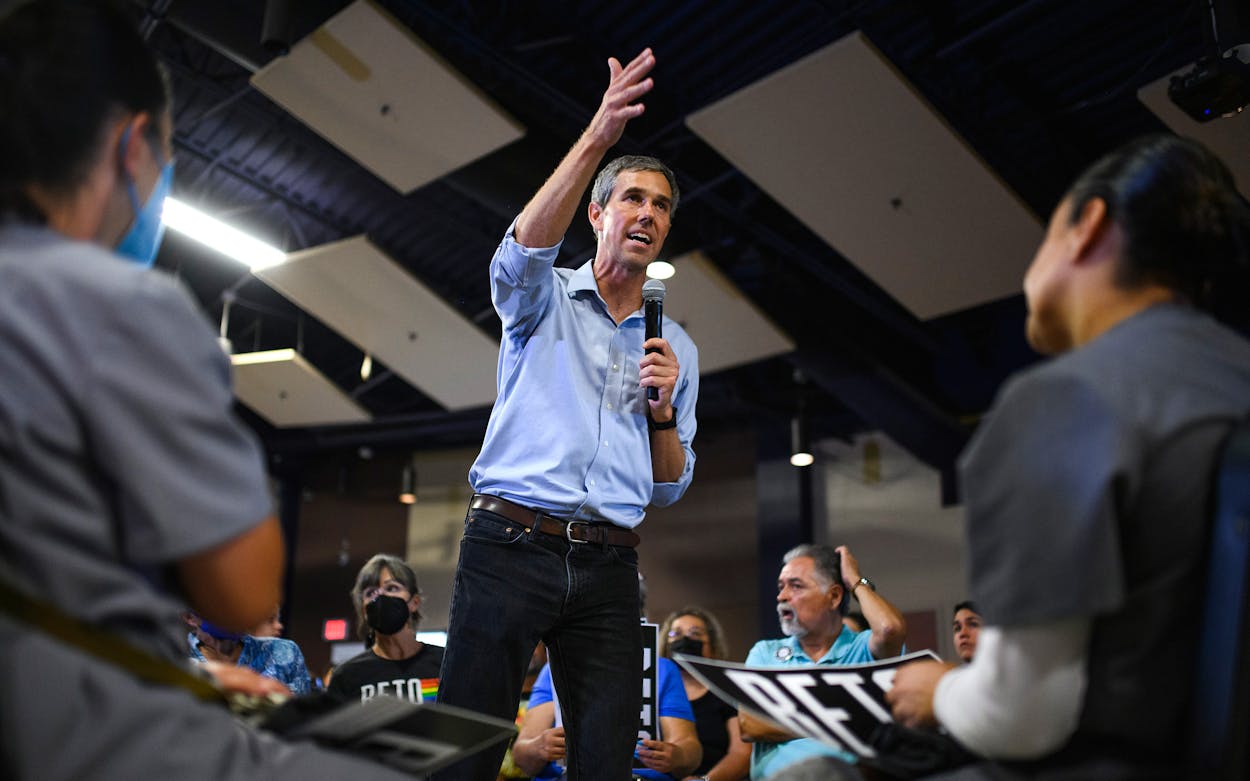

Depending on where in Texas Beto O’Rourke was speaking, his campaign speeches during his 49-day summer tour of the state could go one of a few ways. In places where he was addressing enthusiastic supporters, the Democratic candidate for governor would swagger into the center of the room—wherever possible, he holds his events in the round, a nod to ancient Greek theater that seems appropriate for someone who named his first son Ulysses—and begin by declaring that he had “big news” to deliver. He’d take his time before revealing that news: “We’re going to win this election on the night of November eighth.”

Then he’d tick off a list of reasons that sounded more like campaign talking points. For one, as he put it in the Austin suburb of Pflugerville, “We’re going to win because we are fighting for every woman to make her own decisions about her own body, her own future, and her own health care.” He’d then proceed to build toward a crescendo as he hit on the other major themes of his campaign—gun control, marijuana legalization, Medicaid expansion, teachers’ pay—and the crowds would eat it up.

In those settings, filled with supporters wearing their circa-2018 “Beto for Senate” T-shirts, it was easy to flash back to the time when O’Rourke was still the hotshot newcomer bursting onto the national Democratic scene, still riding high on “blue wave” momentum, still being feted by Oprah and Ellen and other mononymous, progressive-minded talk show hosts. At times, it could seem as if the missteps that followed after he conceded his defeat to Senator Ted Cruz—such as announcing a quixotic bid for the highest office in the land by telling Vanity Fair that he was “born to be in it,” or declaring in a presidential primary debate that “Hell yes, we’re going to take your AR-15”—never happened at all.

Stylistically, O’Rourke’s 2022 campaign bears a strong resemblance to his 2018 effort. He’s still driving around Texas in a Toyota Tundra, still drawing crowds in the reddest parts of the state, still guerrilla marketing himself in sprawling selfie lines. But this time around, he’s positioned himself less as an Obama-style agent of hope and change and more as the righteous opposition to Republican leaders, who, he argues, are the ones who have been waging a culture war that doesn’t represent Texas values.

It’s hard to imagine the 2018 version of Beto O’Rourke crashing a press conference in Uvalde to point his finger at Governor Greg Abbott, as the Democrat did in May. This time, the former congressman from El Paso is playing offense, trying to build a coalition of voters who believe that Republicans’ 28-year monopoly on statewide offices has left them serving an increasingly small minority of Texans. Unlike past Democratic campaigns, including his own, O’Rourke’s 2022 effort is centered on challenging the GOP’s conception of what Texas values are.

O’Rourke’s “Drive for Texas” tour began on July 19 and concluded last week, with many days featuring multiple stops. I met up with his campaign in Abilene on the morning of August 16, continued on to San Angelo later that day, and then caught up with him for two-a-days in Junction, Fredericksburg, Lampasas, and Pflugerville. The high-energy, celebratory gatherings happened in the places you might expect, such as Pflugerville, which is part of the Democratic stronghold of Travis County, but the vibe was similar in some surprising places. In Abilene, where O’Rourke lost by nearly fifty points in 2018, he delivered his big news to more than four hundred cheering supporters in a city that, he joked, “you can see glowing red from outer space.”

But then there were the other events—the ones in deep red rural areas where Democrats are as scarce as thunderstorms have been for most of this summer. Cars outside the venues were decorated with signs that read “Don’t Beto My Texas,” or sometimes just “Abbott,” and protesters waved Gonzales flags, taunting O’Rourke to come and take their AR-15s. Those who came to hear the candidate out were often outnumbered by folks out to declare that their town was most definitely not Beto Country.

O’Rourke tailored his presentation to the crowds. At the tiny public library in the west-central Texas town of Junction (population 2,451) or the old middle school cafeteria in Lampasas (population 7,291), thirty miles west of Killeen, he did not begin by announcing that he’s going to win. In Junction, where ninety or so supporters were outnumbered by at least a hundred protesters outside, O’Rourke’s demeanor was less swagger and more “I hope you’ll hear me out.” He kept his opening remarks brief, by his standards (fifteen minutes or so), saying he was eager to take questions from those who’d spent their morning chanting Abbott’s name. He also took a swipe at his opponent, saying, “They’re fired up because they’ve never seen a candidate for governor in person before,” a line he would repeat in Fredericksburg and Lampasas. At these smaller events, he’d cut to the chase, focusing on core issues—talking about schools, weed, rural broadband, veterans, and at least touching on guns and abortion before opening for questions. The town-hall portions of the events always led to more substantial discussion of the divisive latter two issues.

Sometimes those events would go well for O’Rourke. He might not have persuaded many protesters, but sometimes one of them would shake his hand and thank him for coming to town. And if they waited for him to finish with the selfie line, he’d chat them up one-on-one and try to find some common ground.

Few activities seem to make O’Rourke happier than shaking hands with someone he knows will never vote for him. In Lampasas, he took a break from the selfie line to address two young voters who had split off from the protesters to question him. One of them wore a T-shirt emblazoned with the words “I Hate Liberals,” and O’Rourke was eager to try to uncover some aspect of immigration or gun policy on which they agreed. “I think he’s decent,” Harrison Hays, the Texas A&M student and Lampasas native who wore the T-shirt, told me afterward. Even so, Hays said he didn’t trust that O’Rourke’s scaled-back ambitions on gun control—less “hell yes” and more “let’s institute universal background checks and red flag laws and raise the minimum age of purchase to 21”—mean that he wouldn’t pursue more-aggressive policies if he got into office.

Then, of course, there were times when things didn’t go so well. In August, a clip from one of the more contentious events, in the North Texas city of Mineral Wells, went viral. In it, O’Rourke describes the damage an AR-15 does to a human body, and someone carrying an Abbott sign laughs. O’Rourke spins on his heels and singles the man out—“It might be funny to you, motherf—er, but it’s not funny to me,” he proclaims—before continuing to talk about what happens when someone brings a battlefield weapon into a classroom. These moments also seem to energize O’Rourke.

Even before he formally announced his gubernatorial run, the political prognosticators at FiveThirtyEight ran a story with the headline “Most Candidates Take The Hint After Two Losses. Why Won’t Beto O’Rourke and Charlie Crist?” (Crist is running, again, for governor of Florida.) It was a fair question. O’Rourke certainly knows, if anyone does, how difficult it is for a Democrat to win a statewide election in Texas—no matter how big their crowds and fund-raising tallies might be. (This year, he’s raising a lot of money again—$27.6 million in the second quarter of the year, setting a new record for a statewide candidate. But Abbott, a prolific fund-raiser, still had considerably more cash on hand, and more to spend on TV ads.)

The novelty of his campaigning has long since worn off—O’Rourke has stood on tables to speak to crowds from Iowa to Virginia, and he’s stumped in every county in Texas—and a third loss would be humiliating. And while his 2018 campaign came during an election cycle that was favorable for Democrats, his 2022 campaign announcement last November came amid a slew of Democratic congressional retirements, in the sort of midterm environment that is historically brutal for members of the president’s party. What in the world made him think this was the time to jump back in?

The answer, if you spend any amount of time around him, seems surprisingly simple. O’Rourke does this because he finds purpose in it. He spent 2021 driving around the state serving as a volunteer deputy voter registrar, knocking on doors and holding town hall–style events on voting rights. He went door-knocking in small towns during the dog days of last summer, just to ask whoever answered the door whether they were registered to vote. On the road this year, he talks frequently about how he “fears the judgment” of his children if he’s not trying to make a difference. He waxes poetic about encounters in which he and someone who disagrees with him on everything, except maybe fatty versus lean brisket, share a moment of connection. “At the end of the day,” he told me after one stop on the tour, “we’re Texans, we’re human beings, we want to do right for our kids, and we want to come through at this moment.”

When you see all of this, the idea of O’Rourke as a relentless striver desperate to climb the political ladder—an image that emerged during his presidential bid—doesn’t really add up. Maybe what he told Vanity Fair three years ago wasn’t a regrettable boast, but something that’s at the core of who he is. Maybe he really was born to be in it. And maybe he foresaw some possibilities for Democrats in 2022 that others, at least until recently, did not.

At this point in the midterm campaign, things are looking up for Democrats nationally. Polls are showing that November might not bring the GOP landslide that seemed inevitable earlier in the year. O’Rourke seemed to recognize the reasons for this earlier than most members of his party. From the start, he’s been campaigning on issues that national Democrats have only just begun to emphasize—in particular, championing abortion rights and emphasizing growing threats to democracy, two issues that have emerged as chief concerns for voters. The overturning of Roe v. Wade has led to a surge of women and young, progressive-minded Democrats registering to vote.

If O’Rourke wanted a do-over on his 2018 run, in an environment that’s less hostile than history suggested it would be, he got one. One of the key changes he’s made involves how he talks about his opponent. Four years ago, O’Rourke ran a campaign that rarely acknowledged the existence of Ted Cruz. He was as upbeat a Democrat as you were likely to find in the middle of the Trump era, focused on the better angels of everyone’s nature, seemingly determined to make the election a referendum not on his opponent but on whether voters liked O’Rourke personally. In 2022, though, Greg Abbott’s name crops up frequently at O’Rourke’s campaign events—and not just on the signs being waved by protesters in the back of the room. O’Rourke goes after Abbott for the state’s abortion ban, for the failure of the power grid in February 2021, for refusing to accept federal funds for Medicaid expansion, and for calling a special session to bar transgender kids from playing youth sports—while avoiding any attempt at gun control in the wake of Uvalde.

When I asked O’Rourke what’s different for him in 2022, he immediately brought up the governor. “The biggest difference is Greg Abbott. He’s not one of five hundred and thirty-five members of Congress. He’s the chief executive of a state that failed to keep the power on last winter,” he told me, before reiterating his list of Abbott’s failings. Even the hopeful parts of O’Rourke’s campaign, and his conviction that he can bring Texans together, are framed in contrast to Abbott. “It’s been drilled into our heads for years by the people in power that we’re supposed to be scared of each other,” he said when I asked about the protesters. “I don’t blame some Texans for feeling that way.”

Of course, one can dislike the current governor without running a long-shot campaign for an office a Democrat hasn’t won since O’Rourke was playing bass in an El Paso punk band. When I asked him why he’s doing this, O’Rourke pointed to where the crowd in the Hill Country town of Fredericksburg—which tipped past seven hundred attendees, according to his communications director—had stood a few hours earlier. “I’m doing it for the same reason all these folks came out here tonight,” he said. “We all want to come through, and no one’s going to do it for us.” O’Rourke said that his children—two of whom are now in high school, while his youngest just started middle school—are a big part of why he’s running. “They’re not thinking about this in terms of the impact on their lives, but in terms of what’s happening in Texas and what’s going on in their schools, what they and every other El Pasoan was witness to in August of 2019,” he said, referring to the massacre at a local Walmart that killed 23 people. “I feel so accountable to [my kids], and I so fear their judgment, that I want to make sure that I come through.”

Gun violence is an undercurrent for much of his campaign. O’Rourke talks about it everywhere he goes—and sometimes makes it clear that, even as the policy aims he discusses have evolved, his personal position has not changed much. In deep red Junction, when a supporter told him during the town hall that she doesn’t understand why anyone needs an AR-15, he responded that while he was aware of the political calculus of what Texas voters want to hear, he nonetheless agreed with her. “There’s no legitimate hunting or self-defense reason for having this weapon,” he said. O’Rourke says his reasons for walking back the “hell yes” reflect not a change of heart, but rather a recognition of what’s possible. “It’s not perfect,” he said in Junction of his more-restrained gun control platform. “But if we don’t allow the perfect to become the enemy of the good, we’ll be able to get something done.”

O’Rourke frames most of his campaign messages, no matter how they’re positioned on the left-right spectrum, as matters of pragmatism. “A secret I’ve learned by listening to people is that Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike use marijuana at roughly the same rate in this state,” he said in Junction, adding that the tax revenue the state would bring in if the drug were legalized would be sizable. He notes that the Republican governors of Arkansas and Oklahoma expanded Medicaid, and he frames it as an issue of bringing billions of Texans’ federal tax dollars home.

It’s the same with hot-button issues that tend to inflame the culture wars. Even in conservative cities such as Abilene, Junction, Lampasas, and San Angelo, he talks about voting rights as a matter of honoring the legacy of those who fought for them generations ago. He brings up the state’s hostility toward transgender kids and abortion rights in front of crowds in rural and conservative areas, too.

National Democrats spent much of 2022 avoiding culture-war issues, preferring to keep the focus on so-called “kitchen table” issues. But O’Rourke’s theory of the electorate is that folks in Texas talk about a lot more than just the price of gas or goods. In the immediate aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade, as the Biden administration struggled to respond and congressional Democrats debated whether there was even a point to pursuing legislation to codify abortion rights, O’Rourke was attending rallies in Houston and Austin hosted by abortion rights organizations. Not long after a Greg Abbott strategist boasted that going after transgender kids was “a seventy-five to eighty percent winner” for his campaign, O’Rourke was posting videos on his social accounts of himself cooking a Mother’s Day meal for a family with a trans kid. His message seemed clear: for those families, and the folks who care about them, these are kitchen-table issues.

Still, the question remains: is O’Rourke’s 2022 approach—running to the left, giving common-sense reasons for his positions, and campaigning everywhere—the way to win in Texas as a Democrat? The Abbott campaign has been dismissive of the notion that O’Rourke’s message is resonating outside of his base; Abbott strategist Dave Carney told the Texas Tribune earlier this month that there is “no correlation” between crowd size and electoral results. And the protesters outside O’Rourke’s events often question whether the supporters he draws are even members of their communities. “I’ve seen a picture of the Lampasas County Democratic Party meeting, and there were like five people there,” Hays, in his “I Hate Liberals” T-shirt, told me.

Sometimes, though, the community ties between O’Rourke’s supporters and his protesters are undeniable. In Junction, a group of Abbott supporters had set up on the concrete porch of the town’s library annex, where the challenger would be speaking. The county sheriff stood nearby, ensuring that those who wanted to go inside the building had a path to do so—even if entering required them to pass a gauntlet of folks in red T-shirts chanting “Abbott! Abbott! Abbott!” in their faces. One of the protesters speculated that the Beto supporters must have been bused in from Austin, even though attendees were parking their cars, not exiting a bus, before walking into the building. But then one of the lead protesters noticed someone she recognized walking into the building. “Hello, Alice,” she said, surprise in her voice. “Are you going inside?” Her neighbor responded, “Yep,” and received a pat on the arm on the way in.

O’Rourke is convinced that his positions on contentious issues are popular in more places than those who see politics as a rural-urban divide assume. “Some of our assumptions have proven false,” he told me. “Like the idea that folks in Junction don’t care about the rights of their transgender neighbors, or that people in Canadian, Texas, don’t care about a woman’s right to make her own decisions about her own body.”

Much of what O’Rourke promises to do as governor will be difficult—if not impossible—to accomplish without the support of a state legislature that’s almost certain to remain in GOP hands. Promising to restore abortion rights sounds great on the stump, but a governor can’t repeal a law he disagrees with on his own. When I asked O’Rourke whether his chief role as governor would be using his veto as a backstop against right-wing legislation, rather than advancing his agenda, his sunny response almost strained credulity.

If he beats Abbott, O’Rourke said, Republican lawmakers “are going to be paying attention.” He believes the jolt of his victory will make them receptive to modest reforms on abortion rights, gun control, and immigration. “I think there’s a lot of common ground there,” he said, “and I will make the most of every single inch of it.” He may be right about the existence of common ground. But it’s equally possible that resisting cooperation with Governor O’Rourke would become a requirement for Republican legislators who wanted to survive primary challenges from the right in 2024 and beyond.

Even if we can’t predict what the repercussions would be, O’Rourke is certainly correct that a victory in November would send shock waves through Texas politics. That’s partly because it seems so unlikely. Polling in the governor’s race has narrowed—but from a 15-point Abbott lead last December to 7.2 points on average by the end of August. O’Rourke’s betting odds have improved, too; instead of being a ten-to-one long shot, he’s closer to five-to-one now. That’s a fine trend line if your goal is to score a moral victory. But moral victories don’t change who’s in charge.

O’Rourke learned that lesson the hard way in 2018. But as the 2022 campaign reaches its final months, the candidate is convinced that what he’s seen on the road speaks to something happening in the electorate that the pollsters and oddsmakers haven’t picked up on yet. “As our honorary fellow Texan Joe Strummer would say, the future is unwritten,” O’Rourke told me after his event in Fredericksburg, name-dropping the punk-rock icon who fronted the Clash and whose music can be heard from the speakers at every rally. “We get to decide this at the ballot box.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott

- Beto O'Rourke

- Abilene