On a sweltering August morning, Edgar Ureste recalls, he discovered that he’d left the gate of his corral unlatched and that his horse Corona, a handsome three-year-old brown mare with a white star on her forehead, was missing. Corona, who was born in the early days of the pandemic that inspired her name, had been a gift for his daughter for her fourth birthday. Ureste knew that Camila would be devastated by the news of her horse’s disappearance.

Ureste lives in Boquillas, a Mexican village of around two hundred residents that sits across the Rio Grande from Big Bend National Park. On the Texas side stands the Boquillas Port of Entry, the only means of legally crossing the border inside the park. After realizing Corona was gone, Ureste wandered down to the river, following her hoofprints to the shore. At that time of year, during one of the hottest summers on record, the river was a shallow band of silty, tepid water. When he caught sight of her tracks in the muddy bank on the opposite side, Ureste knew that Corona had entered Texas. He returned home and mounted one of his workhorses, a stallion named Satanás, and crossed the river into the park to find her.

Ureste had heard from neighbors how park officials deal with livestock that enter without permission: they capture them and send them away, and the animals don’t come back. Some, he later heard, were euthanized. So he knew he needed to find Corona as quickly as possible. He wandered the banks along the Texas side and then to the park’s nearby Rio Grande Village, but there was no sign of Corona.

On a hunch, he rode over to one of the park’s corrals, and that’s when he saw her, penned up and alone. Corona whinnied with recognition. Ureste spoke to her in hushed tones, telling her he was sorry, and that he hoped she would have a good life. He knew he wouldn’t be able to take her back; for one thing, the gate was padlocked. And without a visa, he couldn’t ask park officials to assist him; he’d entered the park without permission. Instead he returned home and logged on to Facebook.

Until recently, Boquillas was a town without power. Its residents didn’t have refrigerators or air conditioners or TVs. Then in 2015 the Mexican government built a solar farm in Boquillas, wresting the town from the nineteenth century and granting it internet access, among other things.

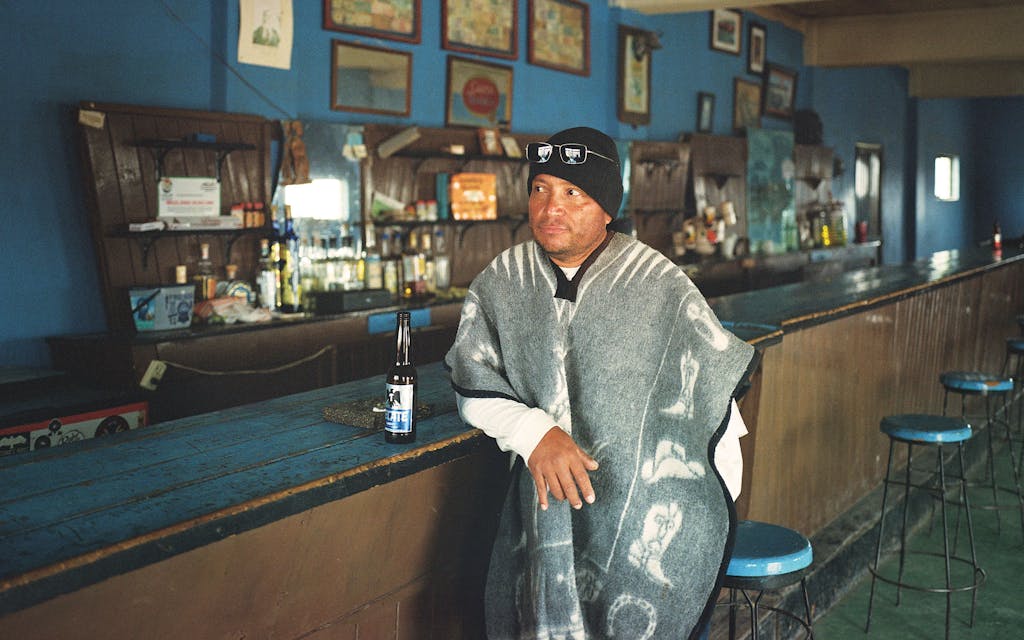

Ureste, who leads hikes through the Mexican portion of Boquillas Canyon, depends on the tourism that funnels from the park. He’s well-known to those who frequent the Big Bend and in recent years has amassed a small following on Facebook. His wife, Adriana Sanchez Valdez, sells local handicrafts and wares on the platform.

On August 18, 2023, Ureste posted a plea for help. “My dear friend Corona made the mistake of crossing the river into big bend ntl park,” he wrote. “My family is heart broken, specially my 7 yr old daughter. Corona was her best friend.” He asked that anyone with news of the horse contact him. The post, which included a photo of Corona, was shared by various Facebook groups, and hundreds of users weighed in, sometimes with ideological agendas in tow. “I’m praying for Corona’s safe return and for your daughters broken heart,” one commenter wrote. Said another, “Illegals can come across from where ever but not a horse. Abuse of government power.” In a region where horses are venerated, that Ureste could not simply reclaim Corona seemed unfair—cruel, even. According to Big Bend National Park’s information officer, Tom VandenBerg, park employees were threatened on social media.

Among those who came across Ureste’s post was Deborah Glenn, an Austin environmental scientist and minister who spends a lot of time in West Texas. Glenn recognized that Corona was blameless. “It was just being a horse,” she said. Looking to put some spare time to good use, she reached out to Ureste on Facebook and contacted park officials, who referred her to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, who in turn suggested she speak to the United States Department of Agriculture. After several calls, she discovered that Corona had been transported to a USDA facility more than a hundred miles northwest of Boquillas Canyon, in Presidio, the site of another international port of entry. With Ureste’s blessing, Glenn made the eight-hour drive from Austin to confirm that the horse was there.

Ureste learned that if he wanted Corona back, he would have to pay for not only the cost of housing her at the facility—$30 per day—and some medical bills but also her transfer back across the border, which would run to hundreds more dollars. There were other complications to consider. Without a passport Ureste wouldn’t be able to pick Corona up; he’d have to get someone else to bring her into Mexico. And that person would have to do so via Presidio’s port of entry—a nearly nine-hour trip from Boquillas along dirt roads. Ureste, who didn’t own a truck, would have to get someone to drive him. But he felt there was no other option. “Corona’s like a family member,” he said.

Unable to foot the bill, Ureste and his wife started a fund-raising campaign, selling T-shirts on Facebook bearing Corona’s face and the slogan #FreeCorona. Nearly a month later, Ureste was able to pay the USDA’s bill, and Corona began her journey home.

Glenn volunteered to pick her up in Presidio and take her across the border. It was an arduous day: The crossing was due to close at five, a deadline Glenn and an acquaintance who was assisting her nearly missed after spending hours trying to coerce Corona into a horse trailer while the hot September sun bore down on them. Eventually they made it across, where Ureste was waiting with a friend who’d brought his truck. Without much fanfare—everyone was too stressed to celebrate—Corona climbed the tailgate without hesitation and lay down on the bed of hay that had been made for her.

Raymond Skiles dedicated much of his three-decade career with Big Bend National Park to the issue of “trespass livestock,” the official term for farm animals that enter the park without permission. These wayward creatures, who trample vegetation and cause soil erosion, have presented park officials with one of their biggest environmental challenges. They also threaten archaeological sites by rubbing up against rock art and historic structures. And they eat—a lot. In 2018 the park estimated that trespass livestock consume about 1.5 million pounds of vegetation annually, in a region where such forage is scarce.

It’s a problem as old as the park, which was established in 1935, and it’s one that Skiles, a retired biologist, gets emotional about. “This is supposed to be a preserve for nature—not to be trampled and eaten,” said Skiles, who was deeply involved in creating the National Park Service’s Trespass Livestock Management Plan. “It’s a place for visitors to enjoy a natural condition, not to have to shovel s— out of their campsite.”

The protocols involving trespass livestock may seem harsh, Skiles said, but there’s good reason for them. In the past, the park tried issuing tickets to folks whose animals crossed, before returning the animals to their rightful owners. It tried pushing livestock back into Mexico without any penalty at all. But neither of those options worked (and both of them were, technically, illegal). Soon enough, those same animals had crossed back over. “The only thing that seems generally effective is to create a cost to having animals on the wrong side of the river by removing them,” Skiles said.

On the Mexican side of the park’s 118-mile border are numerous small ranches with horses and burros and cattle that are oblivious to lines on a map. “They don’t know any better,” Ureste said. “They don’t know they’re over there illegally.” Skiles suspects that the animals’ owners often know what’s going on, though. Boquillas and the other nearby villages rely on the desert’s scarce resources, which can support only a small number of grazing animals. “The folks could see that the grass is greener on the other side,” Skiles said, noting that the land in Mexico has been subject to constant grazing for centuries. He couldn’t help wondering if Ureste had let his horse cross the border in search of food.

Though Skiles is sympathetic to the livestock owners’ plight, he has less patience for park officials, who he says have eased up on enforcement in Big Bend. “The National Park Service for nearly the last six years has failed almost entirely to protect natural and cultural resources that are being trashed on a large scale,” he said. (Park officials did not comment on Skiles’s claims.) And livestock numbers are steadily increasing. The latest aerial survey of the park, according to VandenBerg, counted 376 trespassing animals, well above the annual average of 105 that were documented between 2010 and 2014, though the actual numbers are likely much higher.

The first time I spoke to Ureste, in October, was through Facebook Messenger. He asked me to call him after 9 a.m., explaining that Boquillas’s shaky electric grid was more reliable in the late morning. The solar array was, reportedly, built for a town of seventy homes, but now there are ninety, and the grid can’t always handle the demand. It often shuts down multiple times a day.

We agreed to meet on a Friday in Boquillas, where I would be introduced to the famed Corona, who had recently returned home. Ureste asked if I could bring him a Lone Star beer and promised to pay me back. “We dont get american beer here,” he wrote. It seemed like a fair enough trade: I would bring him a Lone Star—actually, I decided, a few—and he would take me to Corona.

I wasn’t sure if I was allowed to take beer across the border, so I wrapped in my sweatshirt three bottles from the six-pack I had purchased and placed them carefully in my tote bag, leaving the other three in my car. But the customs agent at the border crossing didn’t seem to care what I carried with me so long as I had my passport. I followed the footpath down to the shore, where I saw Ureste smiling at me from across the river. A man ferried me in a rowboat. The water was low and still; after only a few strokes we were on the other side.

Ureste was accompanied by his dogs: Roxy, a pit bull mix, and Abandonado, so called because of his origin story of abandonment. A group of horses and burros waited beneath a pergola that offered a bit of respite from the heat, their ears flicking manically at the cloud of flies that hovered above them. I paid a man $10 and rode a burro into the town, about a half mile from the shore, while Ureste walked beside me. “This is how I get my exercise,” he said.

Almost immediately, he asked me whether the rumors of the federal government shutting down were true, which could be devastating for a town that relies almost entirely on American tourism. The last time there was a shutdown, in late 2018 and early 2019, the border closed for 35 days. Edgar and Adriana set up a table atop a sandbar in the middle of the Rio Grande and sold tacos to folks from the park who were willing to wade into the river. “We still had to make a living,” he said.

Boquillas is accustomed to improvising in the face of unanticipated challenges. But some challenges are too monumental to overcome. After 9/11, the U.S. government shut down the Boquillas border crossing, previously a place where people could pass through without passports. Folks would just come and go, Skiles told me. “It was a wonderful, international time.”

The border remained closed there for eleven years, and the park tourists who would patronize Boquillas’s restaurants and buy its handicrafts all but disappeared. Residents could no longer purchase basic supplies from the park store or fill up on gas. (Their next closest option was Múzquiz, more than four hours’ drive to the southeast, untenable for many who don’t have cars.) “It became a ghost town,” said Ureste, who moved away during that time. Then in 2013 the crossing reopened—only now it was an official port of entry, and though Americans with passports could cross over, few local Mexicans had the documentation that would allow them to move in the opposite direction.

As it turned out, my own trip across the border was somewhat futile. Corona, Ureste explained to me, wasn’t here. She was pregnant, he said, and required more food than he could afford. He had decided to turn her out in a field in Sierra del Carmen, a grazing area at the southeast end of Boquillas Canyon.

Sierra del Carmen is a challenging two-day ride on horseback from Boquillas. That Ureste would go to the trouble of taking Corona there brought to mind Skiles’s belief that the townspeople on the Mexican side may purposely let their animals graze in Big Bend, which is much easier to access. Had Ureste, I wondered, allowed Corona to cross the border back in August and chosen not to do so now because he couldn’t risk losing her again?

As I sat opposite Ureste at a small restaurant in town, he admitted that folks out here will let their animals graze in Big Bend—why wouldn’t they when there’s grass to eat? But he wouldn’t have allowed Corona to cross over and risk capture, he insisted. “She’s family.”

Before I got up to leave, I handed Ureste the beers I’d brought over and explained that I had the other three bottles in my car, if he wanted them. “I don’t want to anger the beer gods,” he said and accompanied me to the port, then waited for me as I crossed back over to American soil and retrieved the remaining Lone Stars. When I returned to the border I saw him standing behind the tall steel barrier while Abandonado waited patiently at his feet. Grinning, Ureste extended his arms between the bars and accepted the gift.

This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Why Did the Horse Cross the Rio Grande?.” Subscribe today.