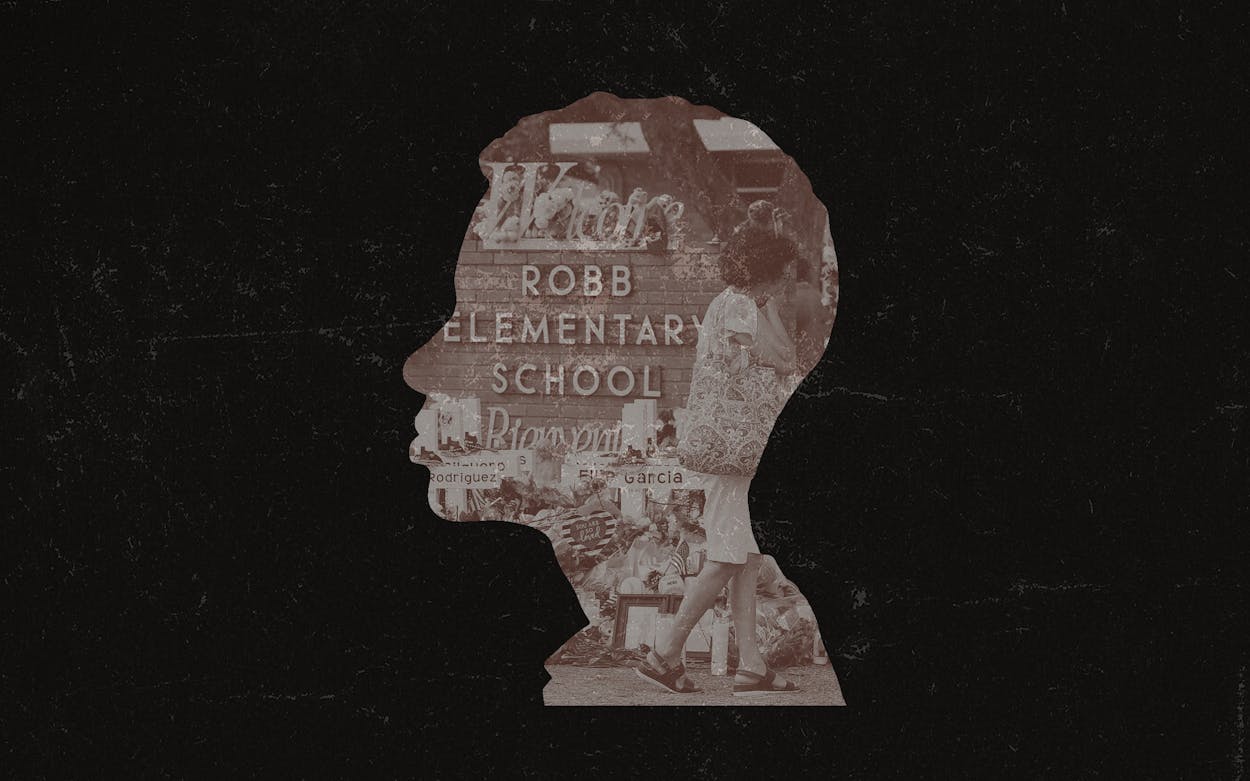

In the wake of the massacre in Uvalde, another insidious danger is threatening the community: a burgeoning mental-health crisis. We cannot ignore the fallout of mass shootings. Left unchecked, this unfolding health crisis will eventually harm, or even kill, more Texans. The mental-health infrastructure in Uvalde, as in so many other towns, has been neglected by the state and federal government for decades. But now we have the opportunity to stop further collapse and to rebuild that infrastructure in Uvalde—and in cities and towns across Texas and the country.

Providing mental-health resources without enacting gun reforms is a mistake, and will not alone solve the crisis. By not doing enough to address gun violence, officials in Texas are making the already desperate mental-health crisis worse—mass shootings create new patients. This broken system cannot withstand the thousands of patients just created.

But Texas does need to improve access to mental-health care. The state is home to more than 10 percent of the nation’s children, and is ranked forty-sixth in the nation for overall child well-being by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a philanthropic organization focused on improving child welfare.

In October 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association announced that the state of child and adolescent mental health is a national emergency, and that the problem is particularly acute in communities of color. In a recent ranking of access to mental-health care, Texas ranked fifty-first in the nation, behind all other states and Washington, D.C.

Specifically, Texas faces an acute shortage of licensed mental-health professionals. In a 2020 report, the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health at the University of Texas at Austin found that out of the 254 counties in the state, 173 did not have a single licensed psychiatrist. An additional 24, including Uvalde County, had only one psychiatrist to serve the entire population. Uvalde was a “mental health desert” before the tragedy. This means that, for children and adults in urgent need, the wait for can take months or more than a year.

In the days following the massacre, many Texas legislators blamed “mental health” for the shooting, not gun violence, and made overtures about needing to improve care. And yet, just weeks before the massacre, the state cut $500 million in programs in order to fund Operation Lone Star, a state border policing operation. Almost half of the cut—$211 million—came from the budget of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which oversees mental health care, in addition to Children’s Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and other critical, evidence-based programs that directly affect the health and well-being of children.

After the Santa Fe High School shooting in 2018, Texas lawmakers passed legislation to create the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium to improve mental-health care for children and adolescents and coordinate care for students identified as distressed. But Uvalde did not benefit from the program, which had not yet been established in the shooter’s school district. State leaders were quick to send Uvalde a $3.3 million Operation Lone Star grant this February, while failing for three years to send the medical professionals desperately needed in the town.

Now Uvalde needs those services more than ever. On June 8, Miguel Cerrillo testified in Washington, D.C., that his daughter, eleven-year-old Miah, a student at Robb Elementary, was no longer the same little girl after the massacre. In prerecorded testimony played at a congressional hearing, Miah shared an account of unbelievable fortitude. She explained how, after witnessing the murder of her teacher and classmates, she used her teacher’s phone to call for help. She survived the long wait for aid, as she lay injured with shrapnel wounds, by covering herself in her friend’s blood and playing dead.

Miah is what some might consider one of the “lucky ones,” the kids who survive these atrocities. Recent data shows that firearm injury is the leading cause of death in children in the United States. This, in and of itself, is beyond tragic, but what is often glossed over in discussion of this horrific statistic is the fact that for every death, countless other children like Miah are injured physically and psychologically.

Children who survive gunshot wounds often face a long, complex, and painful physical recovery. Roughly half of all kids who are admitted to the hospital with a firearm injury leave with a physical disability. Many children require lifelong multidisciplinary care, including frequent doctor’s appointments, therapies, and treatments. Caring for these kids would be difficult for any family. For those with additional barriers such as economic hardship, limited transportation, jobs that do not offer paid time off, or reduced health literacy, accessing care is a monumental task. And there are many such children in Texas, where 19 percent of kids live in poverty. Zoom in on Uvalde, and child-focused statistics are even more grim. Thirty-one percent of children in Uvalde County live in poverty, while 73 percent of students are considered economically disadvantaged.

The physical injuries are not the only wounds that need to be healed. The impacts of firearm violence on mental health are complex. Exposure to it is associated with elevated rates of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse. Survivors are also at higher risk of dying by suicide.

We know that exposure to trauma affects children’s development. This may have lifelong implications that not only hurt each child’s ability to reach their full potential but affect the entire community in immeasurable ways. The crisis also extends far beyond just Uvalde. Our state and federal laws and policies have left children vulnerable to unimaginable violence. Since the school massacre at Columbine in 1999, 311,000 children have experienced gun violence at school, But those estimates don’t include the thousands of Uvalde students at other campuses who experienced an active shooter lockdown on May 24 and had to be escorted to their parents by law enforcement. These numbers also do not account for kids across Texas and the country who are affected by fear of what they saw unfold at Robb Elementary on the news. The trauma of the Uvalde massacre is particularly felt by Latino communities, who identify with the victims and whose grief is compounded by the 2019 racially motivated massacre of Latinos by a white supremacist in El Paso.

When it comes to the specific long-term mental-health outcomes following school shootings, research is limited, but there are some takeaways. Some data indicates that children are resilient, particularly when they feel connected to their community and have access to abundant psychosocial resources and support. The State of Texas has committed $5 million for a family resiliency center in Uvalde, to serve as a “hub for community services including access to the critical mental health resources.” It should not have cost the town 21 lives, 17 injured residents, and thousands suffering with grief for aid to come.

Furthermore, $5 million is not nearly enough. The resiliency “hub” is currently located outside of the city and is not accessible by public transportation. Without a coordinated public outreach campaign, too many residents, even those directly affected, are not benefiting from these services. More than a month has passed since the massacre and there are still families directly affected by the tragedy who have not been able to access mental-health resources and who are waiting for urgently needed financial aid. The town already tragically lost Joe Garcia, the husband of teacher Irma Garcia who died two days after his wife was murdered. Many in Uvalde attribute his death to unbearable grief.

So what is the solution?

Officials must address firearm legislation. This is the only way to stop the acute bleeding. The bipartisan gun legislation signed by President Biden in June was a good start, but it doesn’t go far enough. There is abundant evidence that strict firearm laws save lives. Until we enact better policy, events like this will continue to occur.

As we work to stop the bleeding, though, we need to simultaneously work to heal our communities by pouring resources into the mental-health crisis. We have to recognize the profound trauma from not only this event but also from the acts of gun violence happening every day in our communities. The mental-health resources in Uvalde should be easily accessible for students and families, and that infrastructure should be replicated across the state.

We have the opportunity to rewrite history in Uvalde. To not only prevent the city from collapsing but to build it more resilient than it was before. And in rebuilding Uvalde, we have the opportunity to strengthen and protect all of our communities. While Uvalde, and now Highland Park, Illinois, are carrying the trauma of gun violence today, it could be any of our communities tomorrow. We cannot look away.

Monica Muñoz Martinez, PhD, is a historian who documents the long impact of racial violence and massacres. Martinez is a 2021 MacArthur Fellow and Uvalde is her hometown.

Lauren Gambill, MD, MPA, is a pediatrician in Austin and a member of the Advisory Board of Texas Gun Sense. She can be found on twitter @renkate.

Both authors are former Public Voices Fellows at the OpEd Project.