Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

Subscribe

When I started tracing my family’s roots along the border, I began talking to many Mexican Americans and Tejanos who had a very different picture of the Rangers than the one I had known from the movies.

On the first episode of White Hats, we visit the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco to explore how the Rangers’ history and mythology have made them such enduring Texan symbols. Then we drive to South Texas, where historian Trinidad Gonzales talks about recent efforts to bring more attention to stories about the Rangers’ violence against Mexican Americans along the border—including his own ancestors.

White Hats is produced and edited by Patrick Michels and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, who also wrote the music. Additional production is by Isabella Van Trease and Claire McInerny. Additional editing is by Rafe Bartholomew. Our reporting team includes Mike Hall, Cat Cardenas, and Christian Wallace. Will Bostwick is our fact-checker. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Music used in the cold open is from the 1950s TV show Tales of the Texas Rangers. Archival tape in this episode was from WFAA-TV and the G. William Jones Film and Video Collection at Southern Methodist University.

Transcript:

[Truck door slams]

Jack Herrera: Without overdoing it, I have to think that there might be some metaphor here. I’m trying to get back to this history to understand it. To figure out a path forward. And in both directions, it’s a tricky road. Where I’m standing right now, it’s just completely washed away. I’m close to this history. I feel close to it, but . . . there’s those last five miles, of mud and boulders and washed away road between me and what I’m trying to get to, and trying to understand.

I’ve got to drive my truck across a stream now, and head up about twenty miles of dirt road, get back to the highway, and get back to the marker that does remember the people who died here.

Tales of the Texas Rangers theme: These are tales of Texas Rangers, a band of sturdy men. Always on the side of justice, they’ll fight and fight again . . .

When you grow up in Texas, you’re raised on the symbols that define this place: the heroes of the Alamo, wildcatters in the oil fields . . . and the Texas Rangers. No, not the baseball team. Instead, picture this: a stoic, steely-eyed man with a silver star pinned onto his shirt. He’s on horseback, riding through brushland or mesquite or limestone canyons. And he’s wearing a white Stetson hat.

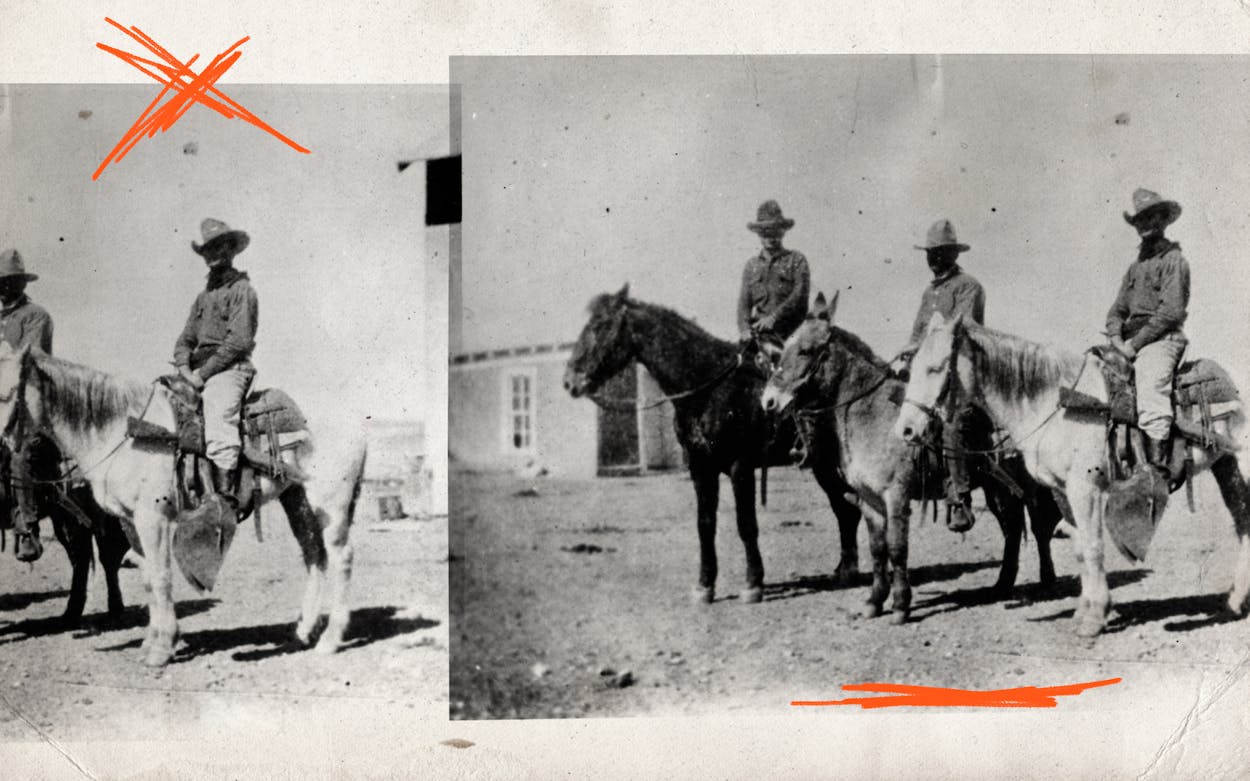

The whole idea of the Western hero—that cowboy-lawman—was born in large part from the Rangers’ true stories. The Rangers were created almost exactly two hundred years ago by Stephen F. Austin, the leader of the first Anglo settlers here. These original Rangers, a scrappy group of ten adventurous men, would become some of the great icons of the American West.

Rangers rode into battle against the Comanche. They helped Texas wage a war of secession against Mexico, and later a war of secession against the United States. They were among the men who finally brought outlaws like Bonnie and Clyde to justice. And they’re not just a vision from the past.

Rick Perry at press conference: “One riot, one ranger” is still prophetic and still true today.

Rangers Tremendous Job Tape: They’re able to do the tremendous job they do because each one of them is thoroughly skilled in the art of scientific criminal investigation.

Univision Anchor: El caso está ahora bajo investigación del FBI y los Texas Rangers . . .

Anderson Cooper: All right. So as you reported, the Texas Rangers have taken over this investigation, the FBI’s getting involved . . .

Mike Jerrick, Good Day Philadelphia: And the Texas Rangers—not the baseball team, the police, the Texas Rangers . . .

Alex Holley, Good Day Philadelphia: No no, not the police. They are different from the police, okay? The Texas Rangers, that’s a whole ’nother level.

Mike Jerrick, Good Day Philadelphia: They ride horses and stuff, don’t they?

Alex Holley, Good Day Philadelphia: And they wear cowboy hats and they have a star . . .

Today’s Rangers tend to ride trucks, not horses, and their guns hold a lot more than just six bullets—but they still turn up wherever they’re needed anywhere in Texas. Texans know that when the white hats arrive, things are serious. Heads turn when they enter a room.

When you remember that our state is just 177 years old, you realize that the Rangers are actually older than Texas. They were founded when Texas was still just an idea. And they were the men sent out to fight to make Texas a reality—at any cost.

From Texas Monthly, this is White Hats, a story of the legendary Texas Rangers—and a struggle for the soul of Texas. I’m your host, Jack Herrera.

Over the next six episodes, we’re going to dive into a history of manhunts and battles. But if you’re from Texas, you know that, in this state, telling history is a battle. From school textbooks to the Alamo itself, we’re in the midst of a bitter fight over how to remember where we came from. And the legacy of the Texas Rangers is where one line in the sand has been drawn.

In the last few years, new research and mass protests against racist policing have sparked a popular reckoning with the Rangers’ history. In 2020, the City of Dallas even took down a statue of a Ranger. But now, Rangers supporters are hard at work raising money for new monuments. And next year, they’ll mark a milestone in their history—their 200th anniversary—with parties and ceremonies all over the state.

It’s hard to overstate how important the Rangers are to some Texans. But to other Texans, that legacy is darker. In Tejano communities, old songs, corridos, tell haunting stories of los rinches, the men in the white hats who kill Mexicans.

My grandma grew up in a Mexican neighborhood in San Antonio. She told me that, growing up, her parents taught her to fear the Rangers. A white hat meant “run.”

I’m not from San Antonio, though. I grew up on the West Coast, but I moved here to report on the border for Texas Monthly. I may be yet another Californian in Texas, but I’m drawn to this state for a specific reason: my family has been on this land longer than Texas has been Texas. Herreras have lived in South Texas since the 1700s, in Laredo and San Antonio.

And when I think of what the Rangers mean to people here, I think about my grandfather, Guillermo Herrera, at home in San Antonio, or out on his ranch in Falls City. My memories of him have the soundtrack of an old western movie . . .

Clint Eastwood in The Outlaw Josey Wales: When things look bad and it looks like you’re not gonna make it, then you gotta get mean.

. . . because that’s usually what he had on.

Clint Eastwood in A Fistful of Dollars: When a man with a forty-five meets a man with a rifle, you said the man with a pistol is a dead man.

A Fistfull of Dollars. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

Eli Wallach in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: You know what you are!!!

His favorite was The Outlaw Josey Wales.

Clint Eastwood in The Outlaw Josey Wales: Well are ya gonna pull those pistols or whistle Dixie?

That one ends after a pair of Texas Rangers riding off out of town. That was my first time learning about who they were. And the Rangers appeared in plenty of other movies too.

Dylan McDermott in Texas Rangers: Rangers . . .

Actually, when you start looking for them . . .

Dylan McDermott in Texas Rangers: Our mission is to stop the outlaw . . .

. . . you start seeing the Rangers everywhere.

Matt Damon in True Grit: That’s right, I’m a Texas Ranger. . . . The Texas Ranger Presses on alone.

Jeff Bridges in Hell or High Water: Ranger down! Call it in, get back!

Jeff Bridges in True Grit: Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!

Sitting on my grandpa’s living room couch, I remember feeling excited when he told me that the Rangers still existed. I’d come from the suburbs in California, and I was amazed to think that some version of that old Texas still existed, a place of six-shooters and horses, and adventure and grit.

The Rangers’ charisma is undeniable: they offer a vision of Texans who are righteous, self-reliant, principled, and powerful. I think we’d all like to think of ourselves that way.

But as much as I want to believe in that legend, it’s been hard to live here today and not feel some ambivalence about the Rangers. One of the most consistent fantasies in old westerns is the idea of good guys and bad guys. I’ve been a reporter long enough to know that a story is pretty much never that simple. While the Rangers really have saved lives and have shown singular bravery, their history is also complicated . . . and bloody.

When I started tracing my family’s roots along the border, I began talking to many Mexican Americans and Tejanos who had a very different picture of the Rangers than the one I had known from the movies. In their history, the Rangers killed hundreds of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. This era—sometimes called la hora de sangre, or the “hour of blood”—was one of the worst episodes of state-sanctioned violence in this country in the twentieth century. In one particularly brutal massacre in far west Texas, Rangers executed a group of fifteen men in the village of Porvenir—including some teenage boys.

Earlier this year, I traveled out to the desert to stand on the ground where Porvenir once stood.

On a small marker on the highway near the site, I read the names of the dead. Three of them shared my name: Pedro Herrera, Vivian Herrera, and Severiano Herrera.

I don’t think those Herreras were my ancestors, but reading their names on the marker made me realize something. My grandfather Guillermo—who always dreamed of being a cowboy or a lawman out on the range—probably would not have been the Ranger holding that gun: he would have been the man staring down the other side of the barrel.

This is episode one: “Rangers and Rinches.“

This show started with a former colleague of mine here at Texas Monthly. Cat Cardenas. When I moved to Texas, Cat completely changed the way I understood the Texas Rangers. There was a whole hidden history I had never heard about—a history of Rangers murdering people with names like “Cardenas” and “Herrera.”

I needed to get my head around this. To see how the official story of the Rangers compares to stories I’ve heard from families in the Rio Grande Valley and El Paso. We decided to start at a museum.

Cat Cardenas: I mean, you have to make conscious choices when you are curating a museum, so I mean I think it’ll say a lot about how they view themselves or what they’ve chosen to put on display here.

Cat and I drove to the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, in Waco. The museum houses the Rangers’ official archives. But it’s also a roadside attraction built for kids and tourists.

Jack Hererra: Like, that’s where this process of deciding who we are and what our history is, it becomes very overt and obvious. Like, here’s who the heroes are, here’s who the bad guys are.

Cat Cardenas: It’s undeniable how important the Texas Rangers are to the legend of Texas and to the history of Texas. I want to learn more about how that has impacted the Mexican American community, and I want to learn more about the people that we didn’t get to learn about in school.

Moving to Texas, it’s been easy to learn about the Rangers—there are museums built for them—but it’s been much harder to learn about the history of people like my ancestors and Cat’s.

Jack Herrera: My grandfather said something to me once when he was talking about the family history. He said, like—it was very much like a “mijo” moment—he said, “Mijo, I don’t care if they were horse thieves or they were nobles, like I really just want to know who they were.”

Cat Cardenas: I think that’s just the overarching feeling of growing up here and being a Mexican American is that you simultaneously feel such an attachment to this place, and then you just feel such a disconnect because you’re not really given the same amount of information on your own people. And it’s such a great state, but it’s like, where am I in all of this?

[Seat belt clicks; car door shuts]

When I swung open the heavy door to the Ranger museum, one of the first things I noticed were these mannequins dressed in broadcloths and boots—stand-ins for the motley “uniform” that the early Rangers wore.

Jack Herrera: “We’re here with Texas Monthly; we’re meeting with Byron Johnson.”

Receptionist: “Yeah, let me go get him for you.”

Kids and their parents were wandering around the different rooms, and I could hear them calling out to each other from the different exhibits.

Cat Cardenas: I feel like I should have a backpack right now.

Jack Hererra: Yeah, and probably be holding onto a rope.

We had an appointment for a tour with the museum’s director.

Byron Johnson: Byron Johnson, how are you. . . . You wanna come back and we can talk about whatever you need to and then we can go through?

Jack Herrera: Sounds good.

We sit down in his office, which is kind of a museum of its own. The walls are wood-paneled, and it has the shabby charisma of a farmhouse or cabin.

Byron Johnson: This was the old Ranger headquarters. Here, this was the captain’s office. We haven’t done a whole lot to it because long after I’m gone, they may decide in the future they want to turn this back into what a Ranger office looked like in the 1960s.

Byron doesn’t come out of the Rangers’ ranks—he’s spent his career in museums like this one. Before he came here in the nineties, he ran local history museums in Albuquerque and Tampa. He takes a long view of this history, and he wants the museum to tell the whole story of the Rangers, even the difficult parts. But that’s a tough line to walk, because this place isn’t just a museum, it’s also a Hall of Fame. And it’s been attracting tourists since 1968.

Byron Johnson: When I-35 was being built, the city wanted a high-quality attraction to get people off the freeway. They didn’t want to see what you usually saw in Arizona, which is something that said, “Stop, see the live snakes,” or something like that. They wanted something of importance.

Byron says people still come from as far as Kyrgyzstan to learn about the Rangers.

Byron Johnson: And since the doors have opened, we’ve had over four and a half million people. [laughs]

Four and a half million people, to a roadside museum! What are all those people coming for?

It’s interesting to have a history museum for an agency that still exists. Real, live Texas Rangers still walk the earth today, solving murders and missing-person cases and white-collar crimes. I’ve heard people say they’re a lot like the FBI, but for Texas. Today there are 166 Rangers, serving the state’s 254 counties. Company F, the Ranger division that covers Central Texas, is actually headquartered just behind where we’re sitting.

But I think most people come to the museum for the Rangers’ history, the Wild West allure of their earliest days, both real and imagined.

Byron Johnson: One of the things that I ask Rotary clubs and Kiwanis clubs and things like that I’m speaking to is what is the largest entertainment franchise out there? And of course, right now everybody says, “Oh, it’s Marvel. They have twenty-eight movies.” And I said, “Well, not quite.” There have been over 230 movies made about the Texas Rangers with a major character going back to 1910.

There weren’t many movies made about anything before 1910. The first Lone Ranger show aired on the radio in 1933, and on TV in 1949. In other words, pretty much as soon as we started telling stories in any new medium, there were stories about the Texas Rangers.

Byron told us that there are as many as four thousand books about the Rangers, and the first was printed in the 1840s. That’s just two decades after they were created.

The Rangers have always had fans, which you see in the flashiest part of the museum: a room filled with Rangers memorabilia.

Jack Herrera: A bunch of lunch boxes with Lone Ranger on it. Lone Ranger flashlights, little figurines.

Patrick Michels: A rubber ducky.

Jack Herrera: “Hi-yo, Silver” kerchief with a certificate of authenticity.

It’s a whole fandom—it reminds me of a friend I know who collects Star Trek action figures. There are toy badges from the old Lone Ranger Kids Club. Even a doll of Shirley Temple dressed as a Texas Ranger.

Byron Johnson: Well, this case is on Walker, Texas Ranger, which everybody knows. We have a pair of Chuck Norris’s theatrical pistols, which are cast resin.

He pointed out the belt buckle that Chuck Norris wore in the show, which he says came from the museum gift shop! But I could hear in Byron’s voice—and honestly, this has come up a lot in my reporting—that as someone who’s concerned with the real history of the Texas Rangers, he has a complicated relationship with Hollywood.

Byron Johnson: We wound up working with them on, how do real Texas Rangers actually operate and what do they do, et cetera, cetera. Well, like most theatrical productions, they listened to us very politely and then basically did what they wanted to do.

Hollywood has been obsessed with telling Ranger stories for a long time. And here’s the thing: so have the Rangers. They’ve always loved telling their own tall tales.

Byron Johnson: This is probably the most treasured single item we have in the museum, with one of the more interesting stories.

Byron led us to a large framed oil painting of a young man in a brown animal-skin frontier shirt, and he’s sitting on these rocks, reclining on a scenic precipice with his rifle at the ready.

Byron Johnson: This is Jack Hays, who was arguably the best-known ranger commander in the 1840s.

The stories about Jack Hays are wild. He once charged headlong into a whole group of Comanche warriors, riding side-by-side with the Lipan Apache chief Flacco. There are other tall tales, including a famous shootout where Hays apparently fended off four score of Comanche warriors, entirely by himself, by—get this—climbing to the top of a huge rock.

Hays commissioned this portrait of himself, which shows him in the midst of that shootout in the rugged country outside of San Antonio. Here, I gotta be honest: my producer Patrick and I cracked up when we saw it: there’s what looks like a giant ocean behind Hays, as if he’s standing on a cliff in northern California, where Patrick and I both grew up. Unless there’d been a biblical flood in the Texas Hill Country in 1841, the painting takes some liberties.

Hays made a name for himself fighting not just for Texas, but for the U.S., when the Mexican-American War broke out in the 1840s. The Mexican Army was formidable—well trained, well equipped, and backed by mercenaries from Europe. This was rugged, frontier warfare.

Just the kind of war for Hays and the other Rangers. In Texas, they had developed a novel strategy: instead of lugging a cannon behind them, the rangers rode on horseback, traveling light with state-of-the-art repeating guns. And they volunteered to join the fight in Mexico. Military leaders like Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee saw them in action; it would revolutionize the way the U.S. fought wars.

Byron Johnson: Hays, because it was the first war with embedded reporters anywhere, Hays became literally a household name in the United States. He was in every newspaper and everything else.

After the war, Hays kept on chasing adventure, which took him to the California Gold Rush. He ran for sheriff of San Francisco County, and that’s where this painting in front of us came from—it was sort of his campaign poster. (Which might explain why the background looks so Californian.)

But Byron sounded a little skeptical . . .

Byron Johnson: . . . and he fought off eighty Comanches with a single-shot pistol and rifle, which if you believe that one, I have some swampland for you.

Whatever Hays was selling, San Franciscans bought it. Look it up! The first sheriff of San Francisco County—and a founder of the city of Oakland, by the way—was a Texas Ranger.

Byron Johnson: It’s amazing. Let’s go over here and talk about one of the more interesting modern twentieth-century Rangers.

A few months before our visit, the museum received a collection of artifacts from another Ranger with his own dramatic stories.

Byron Johnson: We have two of his pistols. They have gold inlay over them, they have ivory handles, they have in large gold letters his initials, M.T.G.

It’s almost funny how over-the-top these guns look. They look like movie props—every gangster’s dream. But they’re the actual guns of Texas Ranger Manuel “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas.

Byron Johnson: And Manuel Gonzaullas was arguably one of the most famous Rangers in the twentieth century. He served in East Texas during Prohibition, and in many cases, he was the only law enforcement in the entire area.

Gonzaullas was born in Spain, and served about a quarter century in the Rangers before going to Hollywood, where he taught movie stars how to walk and talk like a Ranger.

In 1970, when Gonzaullas was nearly eighty years old, a wax museum in Dallas debuted a life-size statue of him. The local TV station WFAA came out to cover it. And Gonzaullas treated them to some old war stories.

Manuel Gonzaullas, interviewed by WFAA: As I put my hand on him, he was playing possum. And he had his right hand laying down alongside of him. And he raised it up. And he had a .38 and he shot me. And the bullet hit me just above the heart and ranged up and tore my good suit of clothes. It scared the hell out of me. And of course I naturally, in self-defense, I emptied my left pistol into him. That was the end of it.

The Rangers museum isn’t large or fancy—there’s nothing in it that will truly take your breath away. But there’s a romance to it all, from the leather saddles to the old paintings of Southwest landscapes. Byron showed us different Ranger badges from over the centuries, the famous silver stars, which to this day get hammered out from Mexican cinco-peso coins. I even got to hold a replica of an old Colt Walker revolver.

Byron Johnson: They’re kind of the Holy Grail for firearms collectors these days.

Jack Herrera: Did you pick one of those up?

Cat Cardenas: Yeah, they’re pretty heavy.

Jack Herrera: Yeah. Two of those in your hands, like in the movies, I almost want to hold this like a rifle.

But we weren’t just there for fun. Cat had a question for Byron.

Cat Cardenas: Earlier, when you mentioned, like all law enforcement agencies, there are these big achievements that they have and then also darker aspects of their history. How does the museum go about kind of incorporating both of those things?

Cat and I had wondered whether they’d get into the Rangers’ violence against Mexicans.

Byron Johnson: We have some exhibits up on things like the Porvenir massacre and some of the other things that happened on the border now, but they’re not what they should be in size.

About Porvenir, they only have one placard, in an otherwise-positive exhibit about Rangers on the border. A card inside that exhibit said that it’s not clear whether Porvenir was a massacre or a firefight. It says it’s also unclear if it was Rangers who fired the shots that killed those men, including those three Herreras.

But there is no doubt. It was the Rangers. It felt like the museum was shying away from telling the whole story; maybe even letting Rangers off the hook.

Byron says it’s been hard to figure out how to fit these brutal stories about the Rangers into a museum that’s also a Hall of Fame, a place of celebration.

Byron Johnson: When I got here in 1996, there was none of the balance in place. I mean, the place basically just told one side of the story and that was it.

Byron says they have plans to expand, and he wants to use the new space to tell a more balanced history. But as of today, pretty much every inch of the museum celebrates the Rangers—and there’s almost no mention of their violence against Mexican Americans.

[Road noise outside]

Jack Herrera: It’s good to hear him say, “Is the museum doing enough to reflect that now? No.” And I’m glad he knows that because it’s very obvious to me that this museum is really focused on the heroes and the exploits, which do exist, and are fascinating to read about as a museumgoer. But it really isn’t a full picture of the Texas Rangers.

Cat Cardenas: Yeah.

We talked more on the way home. It hadn’t been surprising that the museum ignored stories of Texans who had been terrorized by the Rangers, the stories of Tejanos and Mexicanos like my family. But I was surprised by how it made me feel. Cat and I were in bad moods on the drive back.

Cat Cardenas: I think when you’re a little kid there’s generally the narrative of good guys versus bad guys. Like when you’re playing pretend and you’re doing little sharpshooter things, knocking cans over or whatever, that’s a very fun thing for kids to think about because it’s binary and easy to understand good versus evil. And the Rangers museum feels like it doesn’t really go past that very much. Of like, these are the good guys. And let’s not ask too many questions about the bad guys, quote unquote, and let’s not ask too many questions about if the Rangers were ever the bad guys.

Trinidad Gonzales: You can go straight; there’s another left here.

This is Trinidad Gonzales.

Trinidad Gonzales: . . . In fact, my grandfather, my grandmother, and my dad are buried over here on this side of the cemetery. My brother’s ashes were spread there as well.

He teaches history and Mexican American studies at South Texas College. We’re in a cemetery in Edinburg, about twenty miles from the Mexican border. Trini specializes in the history of this area, the borderlands where he was born and raised.

On the way to the cemetery, we drove through his old neighborhood—he pointed out the park where he used to get in fights. As we got closer to the cemetery, he showed me the field where he used to play baseball; when a hearse would drive by, he and his friends would pause the game, and hold their hats over their hearts as the funeral procession slowly passed.

Here among the headstones, on a hot morning in Edinburg, he wanted to tell me about his own history.

Trinidad Gonzales: We’re at Hillcrest Memorial Cemetery in Edinburg, Texas. And we’re in the section where my great grandmother, Santos Gamboa, is buried, as well as my grandmother and my mother are here as well. And some uncles and aunts.

Among all of his family here, it’s this woman, Santos Gamboa, who connects to our story about the Rangers.

Trinidad Gonzales: Yeah, right here. This is my great-grandmother, Santos Gamboa. This is her second husband, Juan Garza. She remarried after my great-grandfather was killed by the Rangers, and his father as well.

The death of his great-grandfather and stepgrandfather is why I’m standing here with Trini. So much of his family is buried in this cemetery, but those two men are not. Trini grew up hearing about them, though. In the afternoon meriendas he’d sit down with the grown-ups and listen as they drank coffee and ate pan dulce.

Trinidad Gonzales: As a kid they used to send me to get the sweet bread. “Here’s twenty-five cents, go get pan.”

He learned about how his great-grandmother’s husband had been murdered, and how Santos fought to keep her family together. One day, at a barbecue, Trini’s dad told him the story of what actually happened, the violent break in their family tree in the year 1915.

Trinidad Gonzales: I would hear the story about how my great-grandfather Paulino Serda was killed by the Rangers, and then his father Donanciano were killed. They were killed on the same day. She was there. The Rangers were apparently talking to her. They pulled her husband and her father-in-law to the side. I guess she couldn’t see them, but then she heard the gunshot and she ran to them. Of course she probably knew what was going on.

Their deaths would shape everything that came after. His great-grandmother, who was 35 years old at the time, packed up her kids and moved here, to Edinburg, to start over.

Trinidad Gonzales: And so a lot of stories I heard from my mother about my great-grandmother was about how she came here, and then her life after that. So she has her own cattle brand. My great-grandmother had her own cattle, had dairy cattle that she would produce milk for and she would also rent out. She had a store that was close to where my grandmother lived. And so those stories were always in conjunction with the resiliency of my great grandmother and my family in response to what had happened.

In some ways, maybe, there was much more to say about the family’s resilience than about the murders themselves, which were honestly senseless.

Trinidad Gonzales: They were living out around Laguna Seca area, which is a large ranch where a lot of my family members have worked as vaqueros. And my great-grandfather was the person who had the keys for all the gates, for the ranches.

Nineteen-fifteen was a violent year. Across the border, Mexico was in the midst of a revolution. And at the same time, a group of separatists in South Texas began fighting to return Texas to Mexico. It’s a largely forgotten rebellion.

Trinidad Gonzales: Apparently, the insurgents needed to get through the ranches. They came to him because they knew he had the keys. So, I mean, what was he going to do? Say no to these guys? So he let them get through.

Terrified about the prospect of armed Mexicans on U.S. soil, the state sent in the Texas Rangers.

Trinidad Gonzales: And as a result of trying to avoid conflict with those individuals, the Texas Rangers took him for, quote, a bandit sympathizer, and they arbitrarily killed him. . . . At that time, anybody who was a Mexicano was considered an insurgent or a bandit or a bad person.

This is the understanding that Trini grew up with, of how he and his family fit into the state, and of what role the Rangers’ played in his own family story.

And then he gets to seventh grade. And if you went to school in Texas, you know exactly what that means. Seventh grade is Texas history class.

Trinidad Gonzales: And of course, in nineteen-, was it eighty-two? Seventh grade history. The textbook about the Texas Rangers was: “Texas Rangers good; Mexicans, Indians, bad. They helped settle the frontier and pacified and dealt with . . . So you’re reading that as a Mexicano and reading about the Texas Rangers, and as a twelve-, thirteen-year-old, you’re going through this psychological tension of like, “Okay, my family has told me these stories about los rinches and how they killed my great-grandfather and his father.” But I’m reading it in the official state textbook of Texas saying Mexicans are bad. So that poses a question to Trini at that age, it’s like, “Are my family lying to me? Or maybe my ancestors were bad? How do I deal with this? How do I reconcile what I’m being told at home and what I’m reading in the textbook?”

I asked if he tried talking about it with his family, if they tried to help him make sense of it.

Trinidad Gonzales: Well, this is the early eighties, seventies, Generation X. Having conversations with your family about the psychological dilemmas you’re dealing with is not very common.

So he wasn’t sure what to say when he got back to class.

Trinidad Gonzales: And my teacher was Mr. Garza. And of course, he’s mimicking what the textbook says, “Well, the Rangers were good. The Mexicans were bad. They were bad Mexicans.” And of course I’m not participating because I don’t know how to participate in that conversation. He goes, “Well, don’t believe everything you read in the textbooks. The old people call them los rinches.” It was the first time I ever heard an educator tell me that, or a teacher tell me that. And there was such an affirmation to like, “Oh, okay. My family’s not crazy. I haven’t been lied to, right?”

Trini says he felt lucky to have a teacher who could say that. Mr. Garza had come up during the Chicano movement in the sixties and seventies in South Texas. He could talk about the history in a way the textbooks didn’t.

Trinidad Gonzales: And of course, that was the first sort of critical understanding I think all of us got in that class, that textbooks lie in their interpretations of our community. Regardless of what the state of Texas says. We just learn as you grow up and you build it into your sort of resiliency of living in the United States, that there are people, officially, who are going to lie about our communities and not necessarily really clearly see us as American.

Years later, in 2002, Trini was in graduate school. And he was studying history—in some ways, his family’s history. In his research, Trini was trying to figure out how people in the Rio Grande Valley described themselves before terms like “Latino” or “Hispanic” or even “Mexican American” existed. So he would read old newspaper articles.

Trinidad Gonzales: This was at the University of Houston at the Arte Público archive there on the campus.

He’d spend entire days in a small room in that library.

Trinidad Gonzales: So it looked like a closet that was repurposed. Like a big closet that had probably had bookshelves in there, but it was repurposed to be able to be a viewing room.

And he’s sitting for hours and hours in this room, just him and this big microfilm machine. And while he’s scanning these old papers, he finds one article that stops him, in a newspaper called El Defensor.

Trinidad Gonzales: . . . which was a newspaper published out of Edinburg, Texas, by Santiago Guzman.

Guzman was an early leader of LULAC, the Hispanic and Latino civil rights group, and he writes an editorial about a race for sheriff, where one of the candidates is a local political boss named A. Y. Baker. Ese tipo, Baker, was a former Texas Ranger.

Trinidad Gonzales: . . . and he points out that, “Why should we support A. Y. Baker when A. Y. Baker as a ranger had killed Mexicanos,” right? So I’m reading this and I understand all that history, right? And I get to the paragraph where he talks about, “Why should we support Baker? How can we forget the Matanza?” And of course, I know the term, but that’s the first time I came across the term in this context.

La matanza means something like massacre. It comes from the Spanish word for “pig slaughter.”

Trinidad Gonzales: And, “How can we forget the Matanza? How can we forget the Hinojosas, the Bazans, the Longorias, the Serda,” right? And I stopped and—“Wait a minute, did they say Serda? Was Serda written down in that?”

Jack Herrera: Did you know right away that it was your . . . ?

Trinidad Gonzales: There wasn’t any sort of speculation as like, “Could it be or not be?” I knew it was my family. . . . So that feeling of coming across a document from 1929, that I understood, not as a scholar, but it’s my family history being verified, right? In print.

Of course, he already knew this story. He’d heard about his great-grandfather’s murder from his dad at family barbecues, and then when they’d visit the ranch where Paulino Serda was buried.

Trinidad Gonzales: So these stories were always being told to me. That’s why I said, it’s a part of my skin, I can’t remember the first time I was told the story. I can’t remember the first time I learned this history. I’ve just always known this history. But it was like, here’s the first sort of paper documents I have. A document or a source that’s not an oral history, that correlates to my family’s history. Right?

For Trini, it’s a turning point. This recognition that even when you know your own history, there’s a whole other kind of power in seeing clearly how your story fits into something bigger. In this case, that his family’s tragedy is a chapter in the real story of Texas.

So Trini goes on to get his PhD, and becomes an instructor at South Texas College, where most of the students are Mexican American. Like his seventh-grade teacher, Mr. Garza, Trini helps students find their own history in the history books.

Professor Gonzalez—who early on insisted I call him Trini—helped me understand this history, which is also my own family’s history, in a new way.

Before we met, I read an article he’d written a few years ago that really helped me crystallize some of the ideas I want to explore with you here in this show. The piece that he wrote is called “A Border Antigone.”

Antigone is a Greek play written by Sophocles, almost 2,500 years ago. It’s set in Thebes, during the aftermath of a brutal civil war—between two brothers who each wanted to rule the city.

The violence was senseless, and messy, and at the end, both the brothers are dead. This is how the play opens: over their dead bodies. The new king of Thebes, Creon, says that the city needs a hero; that they need to move on. He declares that one of the brothers will be honored as a hero of the war. As for the other brother on the losing side—whose name was Polynices—Creon orders that the people of Thebes leave his body on the battlefield, unburied, to be consumed by the elements and wild animals. That would be his dishonor as a traitor.

Trini read this story in high school, and it came back to him as he learned more about what happened here during La Matanza, in 1915.

Over the course of just a few months here in the Rio Grande Valley, a shocking number of Mexicano Tejanos were killed by Texas Rangers, as well as by local officials and Anglo ranchers. It was a time of terror. And in the next few episodes, we’ll unpack why this was happening. But first I want to tell one specific story, and I think you’ll understand why.

One day in late September, 1915, two men rode into a Ranger camp to report a horse theft on their land. Sixty-seven-year-old Jesús Bazán, and his 48-year-old son-in-law, Antonio Longoria. Bazán and Longoria—two of the other names that Trini discovered in that old newspaper article. Both were prominent ranchers. Longoria was a county commissioner.

So they reported the horse theft. The conversation seemed to have been uneventful. And they got back on their horses and started to ride away. But then the Ranger captain—his name was Henry Ransom—got in his car with some other men. Antonio and Jesús would have heard it coming up behind them, an ominous sound.

Rangers back then drove Model T Fords, and Mexicans called them cucarachas, because their engines made a clicking sound as they drove. The car noise got louder behind Jesús and Antonio. And then one of the men reached out the window of the Ford and shot them in the back.

Ransom, the Ranger captain, ordered witnesses not to move them from the spot where they fell. Like Polynices, their bodies laid out to rot in the sun. Four days later, though, neighbors went and buried the men exactly where they had fallen.

Even for families that could bury their dead, Ranger killings mark them with a sort of dishonor. Trini’s great-grandmother happened to be there when her husband, Paulino Serda, and his father Donanciano, were killed. She was able to give them a burial, so that Trini could go visit them when he grew up. But Trini says that, to this day, Texas has never recognized their deaths. The state has issued no death certificates. No records. That’s why, at the time, people called these deaths “evaporations.”

Which gets us to what Antigone is about. In the play, Antigone is the sister of the brothers who died fighting each other. She knows they both deserve respect in death. And so she defies the king, and goes out to do what she can to honor her brother. She sprinkles dust over his body.

Trinidad Gonzales: And so that’s essentially what Antigone is about. Antigone is about these moral questions of who do you follow, the greater authority that is divine or the king and his decree? And of course she violated the king’s decree, and the morality of the play is that she ends up being right.

Trini, in his own way, is trying to sprinkle some dust over his ancestors.

[Road noise]

Trinidad Gonzales: So you can probably loop around this way to the left.

After we left the cemetery, there was one more memorial site I asked Trini to show me.

Trinidad Gonzales: And then what we’re going to do is go back to the expressway. And then we’re going to go to, there’s an interchange and it’s going to loop us to the left, going towards Brownsville.

A place that he and a group of historians convinced the state to set aside. To honor the victims of La Matanza.

Trinidad Gonzales: I just realized oh, we just passed it.

It’s easy to miss if you’re not ready for it.

Jack Herrera: You think we can just just turn around here?

Trinidad Gonzales: Yeah I don’t think it’s going to be any trouble.

We got out to take a closer look, standing on some grass off the expressway.

Trinidad Gonzales: During the Day of the Dead—we don’t know who did this—somebody left a wreath here for the marker.

Jack Herrera: So can you describe where we’re standing right now and what we’re looking at?

Trinidad Gonzales: So we’re standing between San Benito and Brownsville on the highway. We’re on a parking area where people can rest.

It was placed here five years ago. And it’s here, on the side of the highway, because this is where many of the victims died.

Jack Herrera: Can you read the sign for me? The marker.

Trinidad Gonzales: Okay. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, racial tensions near the United States–Mexico border and the lower Rio Grande Valley erupted into violence . . .

You can come here, on the southbound shoulder of I-69, to read the whole thing.

Trinidad Gonzales: The section of the highway between San Benito and Brownsville was the site of countless killings of prisoners without due process.

Rangers would show up in San Benito to take prisoners away from local cops and into state custody, and then move them to Brownsville. Supposedly it was for, quote, “questioning,” but many prisoners never survived the trip. It got so bad that the Anglo sheriff of Cameron County told his deputies not to turn prisoners over to the Rangers—he knew what they were going to do with them.

Trinidad Gonzales: It is estimated that hundreds, possibly thousands of Mexican Americans and Mexicans were killed.

Jack Herrera: So what does this marker mean to you?

Trinidad Gonzales: What this marker represents to me is the state of Texas finally acknowledging the past in an accurate way, right? This is how things occurred. And we should remember those occurrences, particularly to respect the dignity of those people who were killed.

It’s just three paragraphs. But it was powerful, standing there and knowing that was where the history played out. Knowing that the drive I just took had been many people’s last.

For Trini, the marker provides some solace. At last, a place people can come and leave a wreath to remember the dead. But to some Texans, it’s a provocation. And as the Rangers prepare to mark their bicentennial, this fight over how to tell their history, whose stories belong in the tale of the Texas Rangers, is suddenly very present again.

Next time on White Hats . . .