The Texas map draws inspiration from as many cultures as any state in America. There’s Czech: Praha, Moravia, Dubina. And German: Breslau, New Baden, New Ulm, and New Braunfels, to name just a few. Scattered across the landscape are small towns with names coming from the Polish (Panna Maria), Swiss (New Bern), Norwegian (Oslo), Danish (Danevang) and Russian (Marfa, Odessa) pioneers who got there first. Plus, to visit most of the great European cities, you never have to leave the Lone Star state: We’ve got Paris, Rome, Athens, New London, Berlin, and Dublin (plus Edinburg if you’ve forgive the un-Scotsman-like spelling).

But aside from family names and others deriving from English and Native American sources (Comanche, Quanah, and anything with Caddo attached), Spanish is the most common wellspring of inspiration for our place names. Often as not, we Texans butcher it, whether we are referring to a town or a street or a river. (Although maybe not so often as those Californians do.)

Yes, we get a few right. We completely nail Laredo, Del Rio, Seguin, Comal (as in the county), and aside from some emphasis and flattened vowels, mostly do okay with El Paso, San Antonio, Bandera, and Concho (again, as in the county). Bosque County is sort of a typically Texan hybrid: locals pronounce it “boskie,” which is close to the Spanish “bose-kay,” but not all the way there, yet nevertheless much closer than “bosk” or “boss-cue,” to rhyme with barbecue.

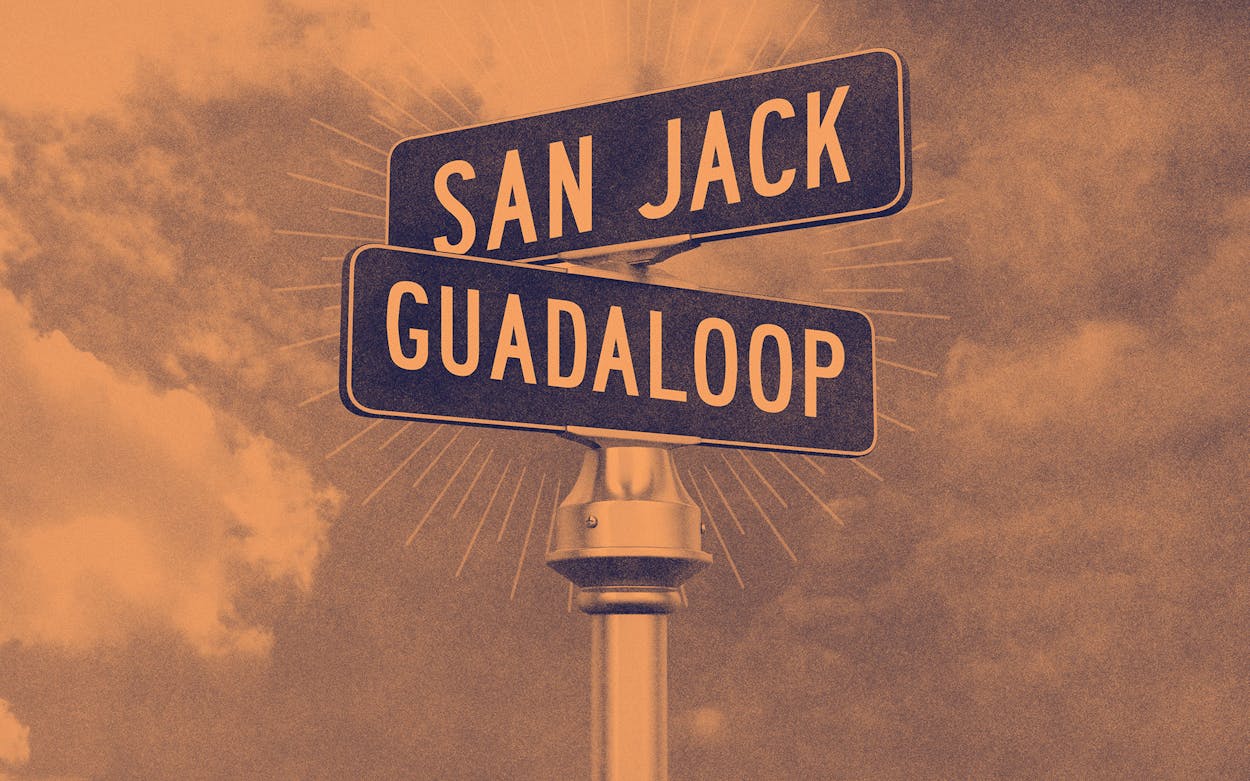

But others we render unrecognizable. It should be “ah-ma-ree-yo,” not “amarila,” or “mo’-rila,” as I’ve heard in bars. “Sahn ha-seen-to,” not “san jacinna.” Refugio should be “ray-few-hyo,” not “r’-feery-o,” and the nearby shrimp port of Palacios should be “pah-loss-ee-os,” not “plashus.” Don’t get me started on how Austinites render Menchaca “man-shack” and Guadalupe “wad-a-loop” or “gwadda-loop.” Like that extra “s” that all-too-often slides into New Braunfels, how did that extra “r” creep into the Pedernales River, rendering it the purda-nalleez? And how the heck did we turn “may-hee-ah” into “m’hay’a”?

But my favorite is the northeast Texas town of Bogada. It’s intended to be named after Bogota, Colombia, but their first mistake was to massacre the spelling. Then the locals compounded that error by pronouncing it, roughly, as “B’goda,” and that is what you call it to this day, unless you want to be mocked as an outsider.

Hell, the entire state is a mispronunciation: If we want to get right down to it, it should be “tay-hoss” instead of Texas. (Or even “tayshas,” if you want to go really old-school Castilian.)

But should we care? Should we cede our traditional Texan mispronunciations because there are now more Anglo Texans with knowledge of Spanish and more native Spanish speakers immigrating from south of the border? Should we be ashamed of our butchery of the Spanish tongue?

Probably not, says Gustavo Arellano, the former editor of Orange County Weekly and the authority to turn to when you needed to “Ask A Mexican.”

“Some people cry racism or whatever, but to me it just shows we have a shared heritage,” he says. “Whether we are fifth- or sixth-generation or not, we are going to call it whatever locals were calling it when they got here.”

Of course there are exceptions. Arellano, a Southern California native of Mexican heritage, cites the relatively recent migration to Southern California from the Midwest.

He blames those middle America accents for turning Los Angeles into that soft g sound we hear universally today (“anghe-les” instead of “ahn-heles”), and smaller towns like Los Feliz from “fay-leez” to “feel-ez.” “But the best one is how they turned a town named after Father Junipero Serra, not into joon-i-perro serra, but into ‘wanperro serra,’” he says.

There will always be sticklers, people who insist on the “correct” pronunciation of the place-names, but even native-born English speakers have problems with English-born names. There’s “hyewston” in Texas and “house-ston” street in New York City (given that it’s originally named after a man named Hugh, score one for Texas there), and Birming’um, England versus Birming-ham, Alabama.

To Arellano, the linguistic change is inevitable. “It’s gonna happen,” he adds. “Americans are going to butcher Spanish names, but I have to say it goes both ways. There is a town near here called Cudahy, and growing up I always heard it [from native Spanish-speakers] was ‘Carra-hie.’ The white locals called it ‘Cudda-hay.’” The same phenomenon is on view in Houston, where Tellepsen Street, named after a Norwegian immigrant, has been rendered into “tailspin” by those living in the barrio nearby.

For some long-time Texans, a sense of guilt is creeping in. Pronounce street names as you’ve always heard them and you risk being shamed by those with a better understanding of correct Spanish. But consider this: Nashvillians don’t pronounce Demonbreun correctly, nor do denizens of “Glasgie” (Glasgow, Scotland). In “Noo Yawk,” locals have so long and so routinely slaughtered the Dutch place names that littered the landscape, we no longer even know that places like Yonkers, the Bronx, and Flushing ever had any connection to the land of tulips and dikes.

Given that, why should residents of Refugio, Bogada, San Jacinto County, or San Felipe Street feel ashamed when they say their place names the way they were taught to?

Whatever will be, will be—que será, será. Or, as we might say, kay sirrah sirrah.