This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Long before we modern folks discovered air conditioning, our forefathers learned to endure the wicked Texas summer by observing the customs of our first landed gentry, the Indians. Those so-called savages survived the stifling Junes, Julys, and Augusts with a minimum of sweat by whiling away a good portion of los días del perro at the local swimming hole. The number of arrowheads, pottery fragments, cooking utensils, and other assorted leavings that have been found around the state’s larger springs testifies to the Indians’ presence.

Like the Indians, most swimming holes were eventually displaced. They fell prey to development, water pollution, and, more important, the evolution of the modern swimming pool, a leisure device that has effectively removed the swimmer from the pool. Have you ever tried to do laps in a kidney-shaped pool? Today swimming in pools is like going to a baseball game in the Astrodome. It can be done, but somehow the hot dogs just don’t taste the same. Now, don’t get me wrong. I know the Old Mill Stream might not be what it used to be. But I don’t believe we are doomed to a life of pouring Murine into our chlorine-shot eyes either.

Swimming holes can be found in every corner of Texas, from the sedate Crystal Springs resort near Maud on the edge of the Arklatex to the historic Big Bend Hot Springs outside Rio Grande Village in far southwest Texas, a stone’s throw from Mexico. All of them harbor the liquid kind of summer magic that can summon up memories of splash fights, cannonballs and can openers, games of Marco Polo, and reddened skin. But swimming holes aren’t merely nostalgic items for me anymore, because swimming isn’t just a pastime. It has become great sport too. Those experts who know about human bodies say that there exists no better form of exercise.

It took me almost four years of swimming regularly to realize precisely why the Town Lake jogging path gets stacked up like Dallas’ North Central Expressway during rush hour: joggers enjoy scenery as much as they like getting healthy. Why spin around and around the high school track when you can run and actually go somewhere? It’s the same with jogging in the water. I swim to feel better, but I want an experience to go with it. So I began to search for the swimming hole of the eighties, a place scenic enough to dredge up all my golden memories yet big enough, clear enough, clean enough, and cool enough for serious exercise.

Flowing spring-fed water is the top priority. If you can’t see where you’re going underwater, half the experience is lost. Besides, stagnant ponds breed disease. The water temperature should be cool, no more than 80 degrees, which prevents bacterial growth. Swimming in water that isn’t regularly tested for bacterial contamination can be as dicey an experience as eating Houston Ship Channel oysters. But in the spirit of Joni Mitchell, who sang about preferring apples with spots to apples treated with pesticides, I’ll take my agua straight.

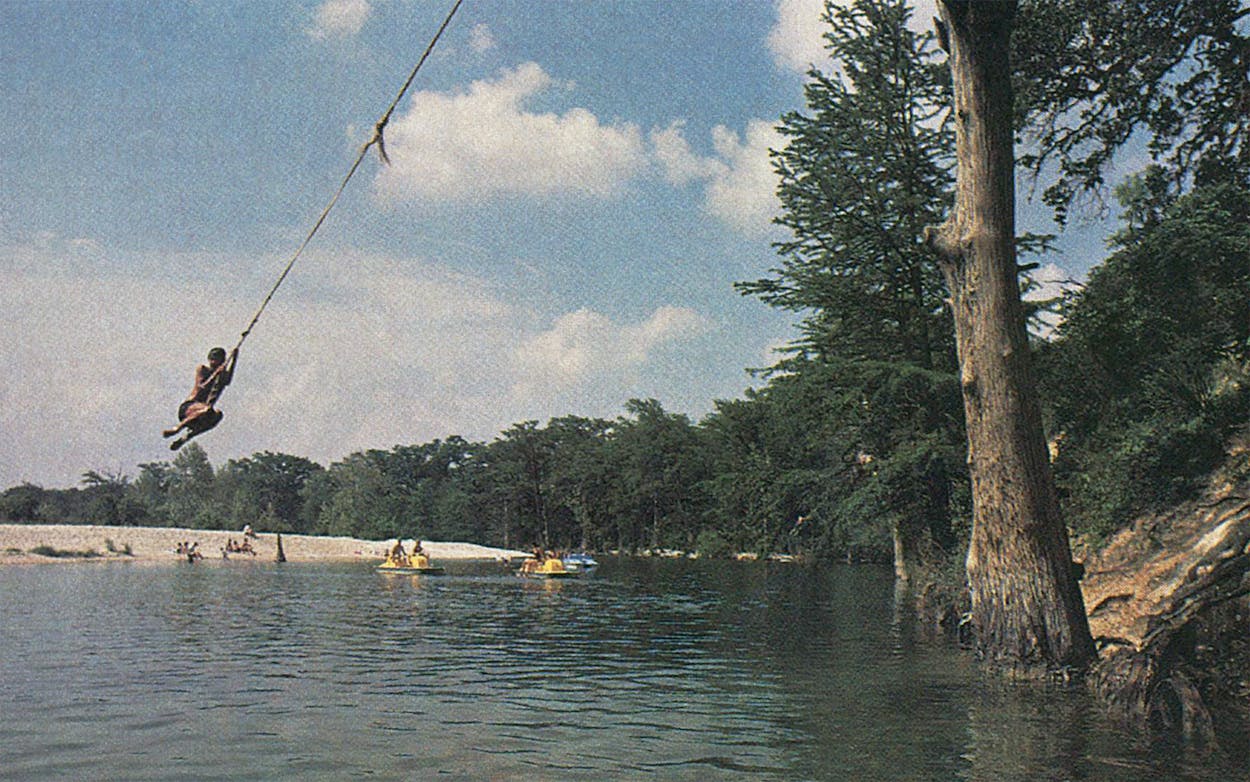

Of course, the area around the swimming hole should be clean—trash cans and rest rooms can be all too rare. Shade trees definitely add to the ambience. So do fish to swim with, big rocks to sit on, ropes to swing from, and waterfalls to look at. Out of respect for private property and out of fear of shotguns, I steer toward swimming holes with easy public access. Remember too that reckless swimming and diving inevitably lead to accidents. Water conditions vary according to rainfall, flow rate, and season, and all rivers and low-lying areas are subject to flash flooding. Use the phone and call ahead.

The majority of the places that met my criteria are in the Edwards Plateau region of the Texas Hill Country—the Country of 1100 Springs, according to geography books and Pearl beer. Above ground, the rolling limestone formations make for the prettiest wide-open spaces this side of the Big Bend. Below ground, the Edwards Aquifer’s vast network of springs provides rivers and streams in the area with a steady flow of sparkling water. Just as Neddy, the moss-eared hero of John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer,” attempted to traverse New York suburbia via backyard swimming pools, you could almost travel from Del Rio to Austin by water if you had enough gumption, bravado, and disregard for the law to jump fences. I’m not quite that obsessed. To me, it’s easier to plunk down $15 for an annual state park entrance permit, procure a pair of goggles, a swimsuit, a towel, a handful of change, and a bottle of Swim Ear, and head down to my favorite spot day after day.

Admittedly, the swimming holes of today aren’t quite as wonderful as those of years gone by. They are endangered as much as the plant and animal life they harbor, especially now that large human populations are tapping into the same underground water sources. At least two managers of swimming holes have expressed the fear that their slices of heaven will dry up within fifteen years if more-stringent measures aren’t taken to preserve the aquifers. But progress isn’t all bad. I’m waiting for the time when long-range cordless telephones are developed. Then during the summer I can take care of business and hone my butterfly stroke at the same time—the closest thing to beatitude I know.

Barton Springs

Austin’s Oasis

Forget Willie Nelson, the state capitol, UT, and the Silicon Whatever-it-is. Barton Springs is Austin. The urban jewel of swimming holes, Barton Springs is the home pool of at least one English Channel veteran, the mayor (“There is no finer place on God’s green earth,” he once told me), sunseekers from all nations, and too many ducks and crawdads to count. In the heart of Zilker Park, the historic spring-fed pool separates Austin from the rest of Texas’ large cities, providing a subtropical retreat in a growing sea of asphalt. The springs have served as a resting spot for overheated humans for centuries. Comanches played here, and three Spanish missions occupied the site during the 1700’s. It became a formal swimming hole around 1837, when Uncle Billy Barton named the place and started charging admission. The pool’s present layout came about in the thirties when Barton Creek was dammed and concrete embankments were constructed. The pool extends 950 feet end to end, though only four fifths of the distance is deep enough for swimming and diving.

Some of the fresh water comes from the creek upstream, but the springs, emanating from cracks in the steep limestone shelf near the diving board, are the primary source of the brisk water. Even when the air temperature exceeds 100 degrees and the humidity smothers the senses like a wet blanket, this body of water maintains its steady 68 degrees. Huge pecan trees and cottonwoods provide ample cover on both of the grassy slopes that flank the pool. During the warm months, the east bank belongs to the sunbathers and scene-makers. The distance swimmers usually stay on the west side near the entrance.

In the last twenty years Austin’s population has almost doubled, and this placid spot less than two miles from downtown has borne some of the overload. The clarity of the pool has diminished, and some days the water takes on a milky hue. Now whenever more than an inch of rainwater accumulates in the Barton Creek watershed, the management closes the pool because of the health hazards generated by urban runoff. On particularly hot weekends in the summer, when three to four thousand people file through the gates, Barton is best appreciated in the early morning or late afternoon, before or after the floaters sully the lower end with their coconut oil. Still, even at its busiest, there’s always plenty of room to put down a towel and take the plunge.

While I’ve read my share of quality-of-life studies, I’m still not sure exactly what they mean. As far as I’m concerned, there’s no better measure of Austin’s character than Barton Springs. As long as the pool is properly preserved and revered by Austin citizens, there is hope for the city that is growing so fast around it.

Barton Springs (512-476-9044), off Barton Springs Road in Zilker Park, Austin. Admission $1.50 for adults, 50 cents for ages 12 through high school, 25 cents for children under 12; additional $2 parking fee on weekends and holidays during the warm months; free parking and shuttle service for those who park half a mile away under the MoPac overpass; rest rooms, bathhouse, lifeguard.

San Marcos River

Aquarena Springs Meets the African Queen

The San Marcos River begins just across the street from the campus of Southwest Texas State University, frothing from a small waterfall where Pepper’s, commonly known as the Old Icehouse, is located. Then it widens into a small lagoon before meandering through the campus, city parks, and back yards of San Marcos. Fed by hundreds of springs in the privately owned Aquarena Springs amusement park, the shallow, steadily flowing river is lined with low grassy banks, huge clusters of elephant ears, and generous shade trees. The foliage is so green and dense it resembles a jungle. If you didn’t know better, you’d expect to see the African Queen around the bend.

In spite of its lush surroundings, the river is a contradiction as a swimming hole. The clear blue water is the finest in Texas, and its constant 72 degrees is only gently shocking to the body. But the river is mostly shallow, and the few deep parts host an abundance of duckweed.

The best way to swim the river is to jump in either at the falls by Pepper’s or by the Clear Springs apartments upstream, across Aquarena Springs Drive from the area on campus where most tubers put in. You can also go downstream to the Lions Club tube rental in City Park, aim the body upstream, and swim against the current. It’s like running on a treadmill, but it works, requiring a brisk stroke to avoid being towed downstream. On weekends that method turns into a real-life video game, the object being to swim in place without getting bonked by the onslaught of tubers, snorkelers, and scuba divers moving with the current.

Collegiate swimmers will have an easier run of the river after the university finishes improving the permanent concrete banks along the Sewell Park segment that flows through campus. The new poollike area will resemble a scaled-down version of Barton Springs. Sewell Park, named for S. M. “Froggy” Sewell, a math professor remembered as the river’s first dedicated swimmer, is for the use of university students, faculty, and staff only, but City Park, adjoining Sewell downstream, is open to the public. Eight miles farther downstream in downtown Martindale lies another swimming hole. A ten-foot dam there is popular among daredevil dam sliders, but the pool isn’t large enough or clear enough to suit me. I only wish regular aquanuts could splash around the headwaters at Aquarena Springs. The only way you can legally do that now is to get a job at the Underwater Theater with Ralph the Diving Pig.

City Park (no phone), Jowers Access Road, and Sewell Park (no phone), Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos (follow the Lions tube rental signs). No admission charge; rest rooms in City Park only, tube and canoe rentals, no lifeguard.

Comal River

Tube Heaven

Billed as the World’s Shortest River, the three-and-a-half-mile Comal winds past the gingerbread homes and quiet streets of New Braunfels. Fueled by the Comal Springs—the largest and grandest springs in Texas and the Southwest—the Comal River has been a drawing card for Indians, explorers, and immigrants alike. During its brief journey before joining up with the Guadalupe, the Comal is perfect for a number of water sports, the primary activity being tubular. There are so many tube rentals and float areas in town that should the tire industry in Akron ever founder, New Braunfels could be designated as America’s new Rubber City.

The two best locations for tubing are old reliables, the Tube Chute in Prince Solms Park and Camp Warnecke. The chute is exactly as advertised, an S-shaped concrete bypass of Stinky Falls, where flour, grist, and lumber were milled in the mid-1800’s. The ride is fast, a little scary, and somewhat dangerous because of the strong, swift current. Tennis shoes are a must if you value your feet. After the chute, it’s only a brief float to the next thrill (and admission charge), at venerable Camp Warnecke, a once-idyllic family resort with a charming screened-in day pavilion out of the un-air-conditioned twenties—it’s cooled by a steady trickle of water running down the metal roof. The grounds have been built up in recent years with a tad too many condos and diversions like go-carts spoiling the scenery, but the lime-green water hasn’t changed at all. A small dam creates Warnecke’s aquatic attraction, a bumpy stretch of rapids that is ideal for tubing. The current not only thrusts tubers along at a quick clip but also makes their return upstream toward the dam almost effortless.

Although tubes dominate the Comal, the serious swimmer is not to be denied. Just below the source of the springs in Landa Park is a landscaped stretch of river with cool, dark blue-green waters and plenty of workout space. This section, known as Hinman Island City Park, is between Landa and Prince Solms Parks. The river is about thirty feet wide and as deep as ten feet here; a straight quarter-mile stretch can be easily swum with a minimum of obstructions. On weekends the heavily used park loses its aura of tranquillity, forcing the swimmer to go underwater in search of solace.

The Tube Chute (512-625-4251), Camp Warnecke (512-625-7296), and Hinman Island City Park (no phone), New Braunfels (follow the signs to Landa Park). The Tube Chute: admission $2.50, rest rooms, no lifeguard. Camp Warnecke: admission $2.25, rest rooms, bathhouse, cabins, no lifeguard. Hinman Island City Park: no admission charge; rest rooms, bathhouse, no lifeguard.

Krause Springs

Water Music

Krause Springs is one of Texas’ most visually and audibly stimulating swimming holes. The pool, at the bottom of an overhanging bluff and surrounded by a stand of towering cypresses (some of them estimated to be more than a thousand years old), is fed by a series of springs at the top of the bluff that join to form a trickling 25-foot waterfall. On most mornings before noon, the only sound besides that of the birds, crickets, frogs, and locusts is the soothing splash of water dropping into the pool. The waterfall, choked with ferns, moss, and elephant ears, lost a bit of its magnificence when the bluff’s overhang sheared off in January. The fallen rock sits in the middle of the pool, a warning to foolhardy divers.

Although the springs attracted at least five Indian tribes in earlier centuries (an undisturbed midden helped place the site in the National Register of Historic Places), the swimming hole wasn’t officially opened to the public until 1963, after owner Elton Krause cleaned up a hog pen on the top of the bluff, constructed a sixty-foot swimming pool and a picnic area, and built several rock canals to channel the spring water through the swimming pool and over the falls. Scattered around the upper grounds are picnic tables, barbecue pits, and rest rooms, all built of native stone by Krause. The landscape includes a pecan grove, cypresses, scrub oaks, mesquites, and junipers, and the area is frequented by white-tailed deer.

The hole is nicer to look at than to swim in. Swimmable space amounts to a 50-by-250-foot area, most of it near the falls, where the depth approaches 8 feet. Because there are numerous boulders in the water around the falls, diving is prohibited. Sunfish hanging out at the base of the falls don’t seem perturbed by human intrusion.

The swimming hole and falls are reached by descending a steep metal stairway and hopping across a shallow stream to a large rock outcropping. On the rocks damming the small creek that feeds the swimming hole, you can make like a lizard and contemplate the ways of the world, a tonic for any stressed-out city slicker.

This relatively small space fills up quickly on hot days—more than ten people around the hole constitutes overcrowding. Arrival before noon is recommended for those interested in aping Thoreau.

Krause Springs (512-693-4181), one mile east of Spicewood, on Spur 191 just off Texas Highway 71 (in Spicewood, watch for signs to Krause Springs). Admission $1.50 for adults, $1 for children 4 through 11; rest rooms, camping, hookups, no lifeguard.

Blanco River

A Swimmer’s Stream

The Blanco is a shallow, swift stream that cuts a particularly spectacular path near the Devil’s Backbone portion of the Hill Country. Along the river are numerous swimming spots, most of which can be reached via private property only. The Blanco State Recreation Area, however, is one of the most accessible swimming locales in the state, since U.S. Highway 281 bisects the park. With downtown Blanco less than a mile to the north, this stretch of the river isn’t overwhelming in beauty. It looks more like someone’s back yard than the wilds. The sloping, manicured banks are dotted with willows and oaks, day shelters, and barbecue pits. The water is cool and refreshing, though the clarity is only fair for a spring-fed river—visibility in the dark green water is limited to just a few feet. Swimming isn’t the main activity here, but it coexists with fishing, picnicking, and camping. Still, there is a relatively uninterrupted run of more than a thousand feet of water for a swimmer to move in. Most people swim above the dam, just to the west of the park entrance. Ladders on either side of the river, and the dam itself, provide access to the water.

Blanco State Recreation Area (512-833-4333), Blanco. Admission $2 a car; rest rooms, camping, no lifeguard.

Little Arkansas

A Slice of the Ozarks

About thirty miles downstream from the town of the same name, the Blanco River runs wild, cutting a path through limestone-layered canyons pockmarked with hardy, gnarled short oaks that cling to the sides of the white cliffs. Tucked away in a corner of this rough countryside is Little Arkansas, or Lil Ark, as it is also known. About seven and a half miles from Wimberley, this rustic, privately owned and operated recreational site can be reached by going east on Ranch Road 3237 on the outskirts of town. At the Corral, an outdoor, sit-down movie theater, turn right onto County Road 173 (Flite Acres Road). Then follow the hand-painted signs (don’t miss the right turn onto County Road 174) for several miles of paved and then unimproved dirt road, crossing the river three times before you get there. Liza Howell, the sunbonneted owner of the grounds, runs her family resort with an iron fist. If one fails to hear her personally lay down the laws of her resort at the entrance, signs scattered about the grounds drive home the point: “This Resort Is for Ladies and Gentlemen Only,” “Don’t Dig Worms,” “Don’t Chop on Trees, Roll Rocks Down Mountain, Disturb Spring, Dig or Pull Ferns,” “No Asses allowed in Springs,” “No Trotlines,” “No Electric Toasters or Skillets.”

All the Noes are necessary because, in truth, Little Arkansas’ ecosystem is fragile. Footpaths have left the delicate limestone surface brittle where several springs run down a heavily wooded hillside before pooling together and tumbling over a short fifteen-foot falls. A small concrete dam has been constructed just up the river from the falls. Upstream from the dam the shallowness of the Blanco limits swimming in the chalky blue-green water, but two riverside docks shade a pleasurable wading area. The water below the dam is even more shallow, but a small hole beneath the falls is deep enough for a good splash. The falls here, like those at Krause Springs, have eroded over the years. If you explore them, stay away from the edge.

The campgrounds do resemble a slice of the Ozarks, with a hodgepodge of cabins, mobile homes, and hookup sites. The place has character and characters. Howell limits admission to families and anyone else she chooses. “I’ve got plenty of customers the way it is right now. I don’t need any more,” she contends. Swinging singles need not inquire.

Little Arkansas (512-847-2767), about seven miles east of Wimberley on County Road 174. Admission $5 a car for day use; primitive rest rooms, camping, cabins, hookups, no lifeguard.

Blue Hole

Cypress Canopies

Less than half a mile from the main square of Wimberley, an artsy Hill Country village that caught the eye of roving tourists long ago, lies the Blue Hole, a narrow, troughlike stretch of Cypress Creek canopied by (what else?) a stand of stately cypress trees. The water is, as the name suggests, deep blue and is cold enough (65 to 68 degrees) to turn your skin the same color.

Blue Hole is a traditional swimming hole. The creek is not really wide enough for a long workout—the swimmable stretch is about 250 feet long. But even the most dedicated lapper tends to forget that drawback in the company of giant trees, two formidable rope swings, tree ladders for diving, and that icon of Texas summers past—a string of light bulbs hanging overhead.

There’s a sense of community at this spot, which World War II troops from San Antonio once used for R and R. One family has held an annual reunion at Blue Hole for the last forty years, and some campers have visited the grounds since the twenties, when the place was first opened to the public. The clientele I encountered on my last visit leaned toward the young, hip, and laid-back. A couple of beat boxes on the premises were tuned to KLBJ-FM, but life at the Blue Hole doesn’t rock. It shuffles somnambulantly. The management reserves the right to refuse service to the rowdy and restricts admissions in those rare instances when the park fills up. This is another area that can lose its charm fast when crowded; swimming is best during the middle of the week in the summer.

Blue Hole (512-847-9127), Cypress Creek, Wimberley (a quarter mile east of Wimberley on Ranch Road 3237, watch for the First Baptist Church; the road to Blue Hole is just to the left of the church). Admission $1 a person or $5 a car (up to four people); rest rooms, camping, hookups, no lifeguard.

Sabinal River

Utopian Memories

I went to Utopia because Nadine Haby told me to. Nadine grew up in Utopia, a sleepy little ranching town in the heart of the Sabinal Canyon, and her eyes got kind of misty one night as she stood behind the cash register of her family’s restaurant in Uvalde and reminisced about the river running through town, the ol’ rope swing, and all the fun she had there. It had been a great place to be a kid, she told me, but she wasn’t sure if it was anymore. Don’t worry, Nadine. Utopia is still almost like utopia and a pretty good place to be a kid in the summer.

The upper dam in the small city park is as pleasant as she described it, with plenty of tall oaks and cypresses hovering over the banks of the emerald Sabinal. It’s easiest to get into the river from the dam, since the muddy, soft bottom at the water’s edge is slippery. Once in the water, swimmers should stay away from the shore to avoid getting tangled in the reeds and bulrushes. Nadine’s swing is still there, and so are some wooden slats nailed onto a tall tree as a makeshift diving platform. But the crowds aren’t. Tourists usually make a beeline for the Rio Frio, less than fifteen miles down the road, and the locals haven’t been caught up in the throes of swim fever yet. The rodeo arena and the baseball field in the city park seem to attract most of the attention these days.

Utopia City Park (no phone), just west of downtown Utopia off Ranch Road 1050. No admission charge; rest rooms, day cabins, no lifeguard.

Rio Frio

Limestone Luminescence

The mighty Frio River springs to life in Leakey, then shadows U.S. Highway 83 to Concan before making its break toward the Gulf, bolstered along the way by a series of small dams that create pools tailor-made for a good underwater workout. The surroundings are spectacular, with the west bank jutted against a high limestone outcropping. Junipers, oaks, mesquites, and cypresses predominate. The limestone-filtered water is a luminescent green, chalky and cool, but not cold. With the water temperature remaining in the seventies throughout most of the year, the Frio is ideally suited for dipping. The bottom along the west bank is muddy, but smooth rocks line the rest of the riverbed. Though last year’s drought was not kind to the Frio—the river flow was so slow that some swimming areas had to close because of high bacteria counts—this year it’s holding up rather well so far, even at Garner State Park, the Stewart Beach of swimming holes. On weekends and summer holidays Garner, halfway between Leakey and Concan off U.S. 83, is often congested, with more than 10,000 campers, swimmers, rafters, and other assorted urban exiles jamming its overused facilities. The visitors are an international bunch. I saw more license plates from Mexico than from any U.S. state. Sound of Garner: Accept’s “Balls to the Wall” blasting out of the windows of a Rabbit with Coahuila plates.

There are ways to enjoy Garner in spite of its popularity. Rope swings line the cypress-studded western bank of the Frio, which moves through the park at a steady clip. If you can dodge the paddleboats and water trikes, you can swim a narrow and straight quarter-mile stretch up from the dam. The day-use area just above the last dam in the park is the best for immersion. Stick to the trench near the west bank, but stay far out enough to miss any wayward cannonball artists flying off the swings.

If the congestion overwhelms you, head to Camp Riverview, a more mundane though no less sylvan setting three miles south, just off U.S. 83, with groomed lawns and tall pecan shade trees. A dam provides a gentle tube run through the length of the camp and a nice but shallow swimming area. This is a family place, plain and simple. Ghetto-blasters are discouraged.

Four miles farther downstream, just off U.S. 83 on State Highway 127, is Neal’s Lodges, a relatively off-the-beaten-path family resort with cabins and campgrounds perched on a high embankment above the Frio. Neal’s swimming hole may not be the largest, grandest, or clearest, but overall it is the best swimming spot around, boasting a deep hole, several rock islands for basking, and giant cypresses on both banks. The west bank juts into a steep limestone-layered canyon wall, which helps provide extra shade in the afternoon. Neal’s once had the world’s greatest rope swing (it was actually a metal chain), but insurance regulations brought it down. Not all the fun has disappeared, though. The low and high diving boards remain, and tubes can be rented on the grounds for those who prefer floating to drenching. The swimming hole is about 75 yards wide and averages 10 feet in depth, ample space for a swimmer to splash and choogle.

It could have been the idyllic setting, or maybe my imagination, but the water seemed cooler at Neal’s than it did upstream. One of the property’s owners, Mike Lynch, said that the water never warms to more than 78 degrees. The whole scene was inspiring enough to prompt one girl to ask, “Doesn’t this remind you of a beach in California?” Not exactly. Left Coast water was never this translucent.

A smattering of trash and broken glass in and out of the water indicated that a few customers have yet to learn the etiquette of waste disposal. But I’m told that the problem is getting better at Neal’s, not worse. And on a quiet morning one Saturday, I was convinced. Time will stand still at Neal’s if you let it.

Since Neal’s limits the number of day-use admissions, early arrival is recommended, especially on weekends.

Gamer State Park (512-232-6132), Camp Riverview (512-232-5412), and Neal’s Lodges (512-232-6118), Concan. Garner: admission $2; rest rooms, dressing rooms, camping, cabins, hookups, day cabins, grocery store; tube, paddleboat, and water trike rentals; no lifeguard. Camp Riverview: admission $3 a car, families only; rest rooms, dressing rooms, camping, hookups, day cabins, snack bar–commissary, no lifeguard. Neal’s Lodges: admission $1.50; rest rooms, camping, cabins, hookups, tube rentals, horseback riding, hayrides, grocery store, cafe, no lifeguard.

Balmorhea

The Desert’s Aquamarine

From a distance the Balmorhea Recreation Area looks like a typical desert oasis with a clump of cottonwoods, willows, ashes, and sycamores rising out of the sandy brown flats. On closer inspection, the white adobe structures on the grounds bring to mind an Indian reservation. It isn’t till you pass through the gates to the pool that the realization hits: this body of water is something out of the ordinary. For starters, the pool covers one and three-quarters acres and holds more than 3.5 million gallons; that’s huge enough to earn it bragging rights as the Southwest’s largest. But its superiority isn’t just a matter of quantity. Every pool is only as good as its water, and Balmorhea’s water makes it the perfect swimming pool–swimming hole combination, neatly balancing convenience and natural beauty.

Once a retreat for Mescalero Apaches and a source of water for Mexican farmers, the San Solomon Springs went modern in the thirties, courtesy of the Civilian Conservation Corps, which walled the springs in, built a Spanish-style bathhouse, installed concrete embankments for easy entry and exit, and landscaped the grounds with grassy lawns; no improvements were necessary to the natural gravel bottom or the springs, from which emanates some of the most enticing water in the world. Its pure, bright color adds new significance to the word “aquamarine,” and looking at it in the hot sun practically blinds you. From below, the visibility is as sharp as that in the Caribbean off Cozumel. The water temperature hovers between 72 and 76 degrees year-round, cool to the touch but not too shocking for the faint of heart. The spring-fed pool is circular, with two armlike appendages—a concrete-bottomed shallow end and a deep end with diving boards. You can jump off the high board and swim a straight stretch of about seven hundred feet to the Spanish-style pavilion at the edge of the springs. Add the scenic backdrop of the Davis Mountains, and Balmorhea rates as the finest freshwater swimming hole in this part of the world, bar none.

In spite of the seemingly desolate desert surroundings, one doesn’t ever get too lonely in these environs. Balmorhea is a magnet for those seeking summer relief throughout the High Plains and Trans-Pecos, and on summer Sundays more than a thousand visitors crowd the recreational area. Still, there is plenty of room for everybody, fish included. Two resident water enthusiasts, the Comanche Springs pupfish and the Pecos mosquito fish, are endangered species of desert fish that remain abundant in Balmorhea and in the canals that crisscross the park.

Believe it or not, some locals complain that the water is not chlorinated, although there are no obvious sources of pollution within a hundred-mile radius of the pool. Thankfully, the water must remain free of chemical treatment because, after it runs through the pool, it is used to irrigate local farms. Besides, the flow of the springs completely changes the water in the pool every six hours. If it’s chlorine they want, they can find plenty of it in North Dallas.

Balmorhea Pool (915-375-2370), Balmorhea State Recreation Area, four miles southwest of I-10 on U.S. 290, Toyahvale. Admission $2 a car; additional admission to the pool $1 for adults, 50 cents for children 6 through 12; rest rooms, bathhouse, cabins, camping, hookups, lifeguard.

Western Springs

Small Wonders

As precious as water is out here, human survival in West Texas has always depended on knowing just where every puddle is located. And though the scenery looks forbidding to the passing motorist, this part of Texas has its share of seductive swimming holes. To the south of Balmorhea, geothermal activity has spawned several hot springs in and around Big Bend National Park, including the Hot Springs on the old J. O. Langford homestead near Rio Grande Village in the park and the Kingston Hot Springs seven miles north of Ruidosa. Neither is really big enough for swimming, but the hot mineral water (105 and 115 degrees, respectively) is great for soaking and is reputed to have restorative properties. The same area is studded with tinajas, natural potholes in rocks that trap water, particularly during the rainy season from May to October. These smaller cousins of the cenotes found in Yucatán are excellent sources of fresh water that is clear, light green, and as deep as fifteen feet; some, such as the Ernst tinaja (seven miles northwest of Rio Grande Village), are as big as twenty by thirty feet. Regardless of the size, these tubs are perfect for cooling off, if not for practicing for your next English Channel crossing.

One certain method of finding swimming holes out West is to follow the watering stops on the southern route of the old Butterfield stagecoach trail, which roughly parallels U.S. Highway 90 from San Antonio to El Paso. Thirsty horses needed fresh water in the frontier days, and it was most easily found in springs along the route in Brackettville, Del Rio, Dryden, Sanderson, Marathon, and Balmorhea. The Marathon Post (which is also known as Fort Peña Park) south of Marathon, is typical of them. The small springs that create a reed-choked pool about one hundred yards in length flow over a concrete dam, then go underground and disappear. As unassuming as this body of water appears from a distance, it is cold enough, with water temperatures in the sixties, to soothe even the most sophisticated savage. Marathon Post lacks any and all facilities, but it’s a welcome spot nevertheless. To get there, turn south one block east of the historic Gage Hotel and follow the road about three miles beyond the railroad tracks to the park.

Joe Nick Patoski lives and swims in Austin.

- More About:

- Water

- TM Classics