This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Nearly within sight of the vast Dow Chemical Company complex in Freeport is the place where the New Brazos River empties into the Gulf of Mexico. It’s called new because the river’s course has been altered a bit to fit man’s needs. Down the rutted beach families play and bikinis blossom and trail bikes kick up sand. On the west side of the river, a long, deserted beach stretches out toward Sargent, accessible only by boat. Once, the mouth of the river was a famous spot to fish for tarpon, spectacular silver fish that can grow larger than a man. Today there are no tarpon there or at Port Aransas, and only a few down the coast at Corpus Christi and Port Isabel. No one knows why the fish have disappeared.

The Tarpon River was not a secret, exactly, but almost nobody went there. Which was always a small shock to me because at times it was full of tarpon.

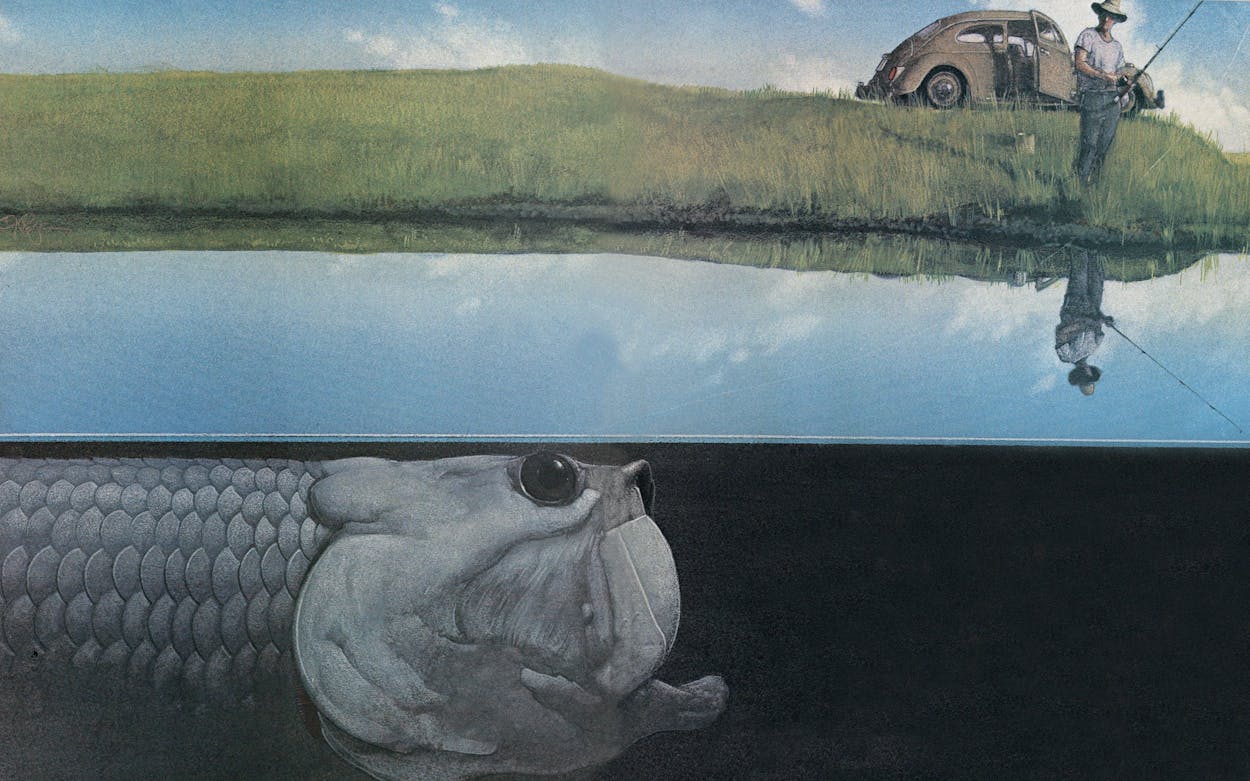

Perhaps it was the beach. To reach the river, you had to drive maybe half a dozen miles of torn-up beach that was really only suitable for jeeps and four-wheel drives. My trusty gray Volkswagen Bug made it most of the time, though, with only an occasional mire. The beach drive was a miniadventure—dodging old wooden pallets and tree trunks and the remains of a campfire, the little engine roaring the best it could with 36 horsepower, low gear naturally, and driving on the hard-packed sand at the water’s edge whenever possible. The surf would be muddy as the surf on the upper Texas coast usually is, but I always had a small thrill of anticipation if the wind had laid and the water settled out. I never stopped and fished in the surf, though.

The beach widened at the mouth of the river and there were dunes and the sand was as white as it gets around here and had a clean look, as if the wind and the tides had scoured everything. I usually parked on the flat part of the beach at the high-tide mark, but if the water was coming in high, I had to stop and find some flat driftwood and run the wheels of the car up on it back in the dunes. Gave you a running start out, and momentum was all-important.

I used what is called a popping rod in Texas, a relatively stiff 6½- or 7-foot, two-handed casting rod with Ambassadeur reel. I never saw spinning tackle used, although it was plentiful elsewhere on the coast. Lures were mullet-shaped sinking style, red and yellow preferred, with about twelve inches of steel leader against the tarpon’s rough mouth and sharp gill covers.

Over the years, the tides had built a sandbar angling out from the mouth of the river roughly perpendicular to the surf. It circled out into the Gulf and you could see breakers maybe a quarter mile offshore. Inside the breakers the river was green with blue glints, and the tarpon were there.

You’d see them rolling, great silver creatures as big as a man, occasionally fretting at the surface as they fed or breathed. Your hands would shake and you’d get caught in half a breath as you tried to toss the plug just so in front of a rolling tarpon. I believed that color and size were not that important, figuring that they would strike the lure out of annoyance more than anything, but I would change colors and try again, just to be doing something. Because the tarpon didn’t strike very often. And when they did, they proved the stories in the outdoor magazines right by throwing the lure most of the time.

More than once I was there before daylight, waiting for the pink light before dawn, with only a subdued roar from the surf to keep me company. Somehow I always believed that I had a better chance at that time of day, a belief that persisted through time after fruitless time of trying.

“The tarpon didn’t just vanish, but they became fewer and fewer until you would see maybe one too far out into the river to reach with a cast.”

I was nuts about the Tarpon River. My fishing buddies would try it once or twice and go back to drifting the bays “where we can catch something.” So I did many trips alone, which wasn’t a bad deal at all. The riverbanks were narrow strips of sand separating the water from the swampy marsh full of rattlesnakes, and I could cover a mile or a mile and a half with tarpon rolling in front of me and maybe one or two other fishermen in sight.

They were a curious bunch, the other fishermen. I called them the tarpon pros in my head because they looked so intent and ready. Their success ratio was probably no better than mine, but you’d never get me to believe it. So I covertly watched what they did and peeked into their tackle boxes and imitated their actions and still didn’t catch a fish.

I would get a bump now and then. That’s how I got the idea that the tarpon were striking out of annoyance rather than for food. It would be just a sudden hard yank, different from the sensation of catching the plug on the bottom, and sometimes a tarpon would burst from the river’s surface immediately, so I knew he had struck my plug.

I’d hate to have a reading of my pulse after that.

Catching a tarpon began to obsess me. I had seen several jump, had a few bumps myself, and had watched one of the tarpon pros land a four-footer from a boat. But I had never connected. It didn’t seem to matter how often I honed the hooks on my plugs or repacked the tarpon kit I had made from an Army surplus binocular case.

I began to practice casting in the back yard. Convinced that accuracy was the key, I spent hours tossing a hookless plug into a bucket. My wife thought I was crazy, but she divorced me later anyhow. And I could hit the bucket more often than not from fifty or sixty feet away.

I got so I would sneak off a few minutes early from my job and race the sixty miles to the river for an hour’s casting before dark. The Volkswagen piled up the miles without complaint and bounced valiantly across that blasted beach again and again, but no tarpon.

I still couldn’t understand why more local people didn’t share my excitement and my lust for tarpon. Here were these fabulous game fish, trophies that people flew thousands of miles for, and they were waiting in the river an hour or so away from Houston.

Why didn’t people fish for them? How come they didn’t make the fishing columns again and again? I couldn’t understand. It was one of those times when I felt out of step with the world.

I’m not sure what happened. Perhaps my backyard practice improved my casting or I absorbed the rhythm of the fish, but suddenly I began to be more successful at the Tarpon River.

On a couple of trips in a row, I actually jumped a tarpon. Again there would be a hard yank and a jump, but this time I would be connected. And stare stunned at the red reel whining at me as line peeled off. The fight never lasted more than a couple of seconds, but it intensified my efforts. All this took place in my third season.

I haunted the Tarpon River long after everybody had quit for the season. I arrived before dawn on Saturday and Sunday, and I stayed until dark and drove that horrible beach back with only the headlights to show me what not to hit.

I had grown accustomed to being the last fisherman chasing the increasingly scarce tarpon in the fall. They stayed in the river longer than the outdoor writers knew, as late as October, when there was a definite chill in the predawn air and nobody else was on the beach.

Fall is the best time on the Texas coast anyway, and I loved the mornings at the river when I hadn’t seen another car on the beach and the tarpon were still around and I had them all to myself. The air was different and the sky was sometimes threatening and I was all alone and it felt very fine, indeed.

The tarpon didn’t frustrate me, which was strange because patience is not one of the few virtues I can claim. But they were so—“magnificent” is the word, hokey though it may be—so magnificent that I was willing to devote the time and energy to them, and I got some reward just for being there. I even felt a touch superior, as if the Tarpon River were a private preserve, mine because I alone was willing to go there.

There must be some sort of justice, because when I finally caught one, I had witnesses. One of the witnesses was my fishing mentor, the man who taught me how to chase speckled trout and redfish in the bays and who was nearly as nuts about fishing as I.

He was not nearly as crazy about the river and the seemingly futile pursuit of tarpon as I, but he would come and cast for a trip or two before going back to the bays and his trout. And the one and only time I caught a tarpon, he was there and saw the fish, so I know I was not dreaming. I would love to write flaming prose across these pages about my one and only tarpon, paragraph after paragraph detailing every lunge and the spray of saltwater and the like, but I don’t remember. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that I was in shock.

I do remember that it was a Saturday and it was blasted hot, the kind of Texas summer heat that makes you take shallow breaths and move cautiously. I do remember that I had moved some hundreds of yards away from my friend because I was scared he would suggest we leave and there were still tarpon showing.

And I remember that yank and the tarpon glistening against the sky and the sound of his body blasting back into the water like somebody had dropped my Volkswagen in the river. And there were runs—there must have been runs because the river was too shallow for the fish to go deep and sulk—and finally he was up against the bank and a tiny wave from a passing boat helped me lift him up on the sand. I remember yelling for my friend and his awkward running as he saw that I had landed one. I remember taking a scale from the tarpon’s side.

I’m not sure whether we fished anymore that evening; I think we did, but I just don’t remember. We did put the tarpon back into the river and hold him gently upright until he caught his breath and moved away.

After that season the tarpon went away. Oh, they didn’t just vanish and I did fish for them for months after I caught that one, but gradually they became fewer and fewer until you would see maybe one or two, like a rear guard or something, usually too far out into the river to reach with a cast. And then they stopped showing up altogether. Some said it was pollution and some just shrugged and some had never fished for them anyhow.

It’s all too bad. There are lots of other kinds of fishing for me now and my tackle and boats are much more sophisticated and I suppose I know a lot more about the sport, if only by the osmosis of two decades of doing it. But the Tarpon River was magic for me and it’s gone.

Once or twice after the tarpon left, I did go and walk the banks with rod and reel ready, but the tarpon were just flat gone. Even my tarpon scale is lost, although my son kept it for me for a while, and the gray binocular case with all the tarpon lures has vanished. The whole thing’s gone.

I do get something of the same excitement now, fishing offshore from my own boat with all the gear and tackle and radios and weather forecasts. But the Tarpon River was special, a ritual and a vocation almost, which sounds rather silly if you’re not me and weren’t there.

The Tarpon River wasn’t a secret, but it should have been. And perhaps there should have been an elaborate initiation rite with tasks to perform and obstacles to overcome before one was allowed to walk its banks.

Actually, perhaps there was.

Peter Barthelme lives in Houston.

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- Wildlife

- TM Classics

- Fishing