It has long been a mystery how, exactly, the Devils River got its name—and what, exactly, happened to the apostrophe. But the leading theory will ring true to anyone who has attempted to navigate it. Though early Spanish explorers named the river after Saint Peter, it’s said that the settlers who followed in their footsteps regarded the waterway and its surrounding terrain as so forbidding that they thought it could have been carved by Lucifer himself. And so the gatekeeper to heaven gave way to the ruler of hell.

Given that grim reputation, that off-putting name, and the river’s remote locale—it begins at the western fringe of the Hill Country and ends in West Texas, near the Mexican border—it’s perhaps no surprise that the Devils is one of the most untouched rivers in the state. As recently as fifteen years ago, fewer than two hundred people a year tried to paddle its length, usually with a paid guide. Many of them no doubt returned home with stories of treacherous rapids that scared off anyone within earshot.

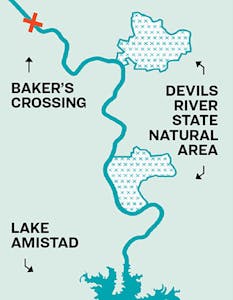

For years, another major knock against the Devils was that there was only one official campsite along its length, at the Devils River State Natural Area’s Del Norte Unit, a 20,000-acre parcel about fifteen miles downstream from Baker’s Crossing (where most overnight paddlers enter the water). Those looking for a place to sleep or dry out were warned not to disobey the ubiquitous No Trespassing signs along the privately owned banks; for years it was rumored that you were as likely to be greeted with a warning shot as a wave.

For years, another major knock against the Devils was that there was only one official campsite along its length, at the Devils River State Natural Area’s Del Norte Unit, a 20,000-acre parcel about fifteen miles downstream from Baker’s Crossing (where most overnight paddlers enter the water). Those looking for a place to sleep or dry out were warned not to disobey the ubiquitous No Trespassing signs along the privately owned banks; for years it was rumored that you were as likely to be greeted with a warning shot as a wave.

In 2010, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department almost doubled the amount of available parkland when it paid $13 million for the nearly 18,000-acre Devils River Ranch, about ten miles north of Lake Amistad, where the current ceases its perceptible flow. As more paddlers came to the area, the TPWD, working with local landowners, opened two more paddle-up campsites, at mile 12 and mile 20. It also opened a campsite on the new parkland, at mile 29.

By one estimate, more than a thousand adventure-seekers now visit the Devils every year. That’s many fewer than visit some of Texas’s other rivers, which is by design: only a limited number of paddlers are allowed on the river at a time. The Devils is not for the faint of heart. It bisects a rough-and-tumble landscape dotted with cactus and patrolled by black bears, mountain lions, and rattlesnakes. During rainstorms, the aquamarine stream can turn into a raging brown torrent, hurling boulders and uprooting trees. The landowners remain a cranky lot. And though there are more campsites, they are still primitive.

But those willing to face such risks are in for something special, especially if they take to the Devils during the spring, arguably the best time to visit. Deep in Devils country are limestone canyons, gin-clear water, prehistoric rock-face paintings, and countless specimens of airborne, waterborne, and land-based fauna. And there is stargazing to beat all stargazing: in January, the Devils River State Natural Area became one of only six International Dark Sky Sanctuaries, meaning it’s one of the darkest places in the world.

Last spring, craving a wilderness adventure, five friends and I—all of us experienced outdoorsmen—decided to dance with the Devils ourselves.

As I paddled my canoe along the Devils River, the echo of unseen whitewater rushing ahead triggered my adrenaline and anxiety. The six of us were a few hours into our thirty-mile, four-day expedition, still adjusting to the river’s drop-and-pool rhythm, a geological pattern alternating between constricted chutes and broad lakes of bright, green-blue water. We should have been exhilarated. But hearing the river’s hydraulic growl in the near distance, I rehearsed my safety-first mantra: when you are on the Devils, you are on your own.

Once we got past the thick canebrakes that obscured what came next, we saw that those first rapids were shallow in the extreme, mainly because of the recent drought. My friends and I quickly jumped out of our boats—a two-person canoe and four one-person kayaks—to push and pull them over the rocks. We were careful to avoid twisted ankles or more serious injuries; help was a long way off, and cellphone service is nonexistent in the canyons. In the early going, we spent much more time wading than paddling.

After we left the first stuttering rapids, though, we encountered an enchanting scene. Leafy willows shaded dappled pools, dragonflies buzzed, butterflies fluttered by, and tanagers, redstarts, and cardinals darted through the air, like flowers taking flight.

After TPWD purchased the Devils River Ranch, local property owners and environmentalists worried that more visitors and expanded access would cause the Devils to be “loved to death.” In short order, TPWD convened a group of stakeholders, ranging from fishing guides to ranchers and state staffers, to craft a plan to provide access while still protecting the river.

As a result, boaters and anglers on the river today must abide by strict guidelines. TPWD issues a maximum of twelve day-trip permits and twelve overnight-trip permits each day, and all must be secured ahead of time. With a few exceptions, anyone making an overnight journey also needs a campsite reservation; each site has a one-night limit. Furthermore, explorers must carry a backcountry toilet setup and a secure garbage container, leave glass bottles at home, follow state boating laws, and refrain from starting open fires on the banks. Break the rules, and fines ensue.

Eight hours into our first day, my friends and I were less than ten miles into our journey, tattooed with bruises and scrapes from negotiating rough limestone chutes on foot. If you’re given to fishing and goofing around, as my companions were, it can take all day to reach the camp at mile 12, the first site below Baker’s Crossing. Although we had our required camping permits, we opted to take advantage of a right-of-way loophole and sort out an impromptu campsite on one of the low-lying islands in the stream—legal but risky if there’s a chance of flooding. We skipped the tents and placed inflatable pads out where we could find flat spots, and then we set up a camping stove to boil water to prepare a dinner of dehydrated packets of beef Stroganoff. Stars emerged as darkness fell, billions of pinpricks showing through the blanket of night; encouraged by the gurgle of running water, sleep didn’t take long to arrive.

On the afternoon of the second day, seriously pink from hours in the sun—we had spent most of the morning using our fishing rods rather than our paddles, slowing our progress to barely a mile an hour—we arrived at the famed Finegan Springs, just upstream of the Del Norte Unit camp at San Pedro Point, mile 15. A collection of hidden rivulets poured off the high cliffs, sending a cascade of crystal water through gargantuan bushes of poison ivy. We spent a long time admiring the fern-furred emerald cliff, kept lush by springs pumping out up to 20,000 gallons per minute.

There was a fierce wind blowing upstream as we approached Dolan Falls, two miles farther on, which is partly encircled by a nearly five-thousand-acre preserve owned by the Nature Conservancy. The falls are considered the true crux of any trip on the Devils. You cannot boat over the falls; for us the trick was lowering our boats and gear down a drop of about twelve feet around the slick, water-carved rocks. They looked like oversized, otherworldly versions of Henry Moore’s reclining nudes.

Though still relatively shallow, the river quickly regained its vaunted muscularity below Dolan Falls, as several more springs added impressive volume. We were having a fine time but knew enough not to be complacent. Anyone who doesn’t respect the hydraulics of this desolate river is courting serious trouble.

After Dolan Falls, we couldn’t resist a little more fishing, abiding by TPWD’s catch-and-release policy for smallmouth and largemouth bass along the Devils. I strung my fly rod, tied on a crayfish pattern, and pulled a couple of nice eleven-inch smallmouth bass suspended in the deep water below the froth. We caught bigger fish on the Devils, but these felt like a prize.

After that lovely respite, the Devils had yet another challenge in store. We arrived at Three Tier Rapid, a series of boulder-strewn shelves approaching mile 19. Thanks to the springs, we were now mostly floating free on the quickened current. As we skirted yet another wall of impenetrable reeds splitting the channel, though, our dinged-up canoe became pinned sideways against a rock. The river was not quite waist-deep, but in seconds the boat was half-swamped as water poured over the side. We were sinking. My sternman hollered to quickly unload our bags so we could free the canoe before the water buried it. This was not the churning thrill of tumping in a whirlpool, but it served as a reminder to pay attention.

Crisis averted, we were on high alert for other demons lurking as we approached the end of our trip. After lunch on our final full day, we cruised past an ancient pictograph high above the river that shows a hunched canine chasing a funny-looking fowl. Archaeologists have documented more than 350 prehistoric art sites in the Lower Pecos area dating back some four thousand years and are still finding new ones. As we continued downstream, pockets of water shone turquoise, a phenomenon caused by the pale limestone along the bottom reflecting the afternoon sunlight. Sunburned and sore, we drifted over deep pools and gaped at fish—gar, perhaps, or catfish—roughly the size of fat baseball bats.

Such a scene would normally have inspired us to reach for our rods, but with the late sun broiling the edge of the desert, the Devils River had seriously reordered our priorities. Everybody stripped to the waist and splashed in the pools. We broke out a snorkel and mask and took turns letting the cool water massage our weary bones while we made friends with the fishes. I felt surprisingly sentimental when I came back up for air; we had only five miles and one night left before the journey came to an end. I didn’t know when we’d make it back. I just wanted to soak in this true blue place.

This article originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Temptation of the Devils.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Parks & Recs