In the last week, three people have died during or shortly after hikes in extreme heat in Texas parks. On June 21, a 17-year-old boy was rescued from the Lighthouse Trail in Palo Duro Canyon State Park and later died at the hospital; two other members of the group survived. Two days later and four hundred miles to the southwest, on Friday, a 31-year-old man and his 14-year-old stepson died in Big Bend National Park after hiking on the Marufo Vega Trail, in the scorching Chihuahuan Desert. A 21-year-old stepson survived and, according to park spokesperson Tom VandenBerg, is now home with family in Florida. In both cases, the hikers were on the trail in the heat of the afternoon, when heat indices had soared to approximately 103 degrees Fahrenheit in Palo Duro and 119 in Big Bend.

Coincidentally, I spoke with VandenBerg, the park’s chief of interpretation and visitor services, about severe heat on Friday morning, a few hours before the latest tragedy occurred. We were discussing a sobering and perhaps surprising statistic: Big Bend has the third-highest per capita fatality rate in the National Park Service, according to a recent Backpacker.com ranking. VandenBerg said the ranking surprised but didn’t shock him. “This is an unrelenting place,” he said. “We’re always sort of surprised when people show up and they don’t know that it’s hot here. . . . Just last week, I was working at the visitors center, and I had two separate groups come in and ask me where the lakes are. I’m not kidding.”

It’s worth noting that these deaths are still exceedingly rare, with only 5.8 fatalities per million visitors in Big Bend, according to the Backpacker.com analysis, which drew on statistics from 2010 to 2020. Texas’s other national park, Guadalupe Mountains, also ranked high on the list, coming in at number ten, with 2.8 deaths per million. (Alaska’s vast Denali National Park is number one, with 9.8 deaths per million travelers; the top causes are exposure and falls. The Virgin Islands, where drowning is a risk, is number two.)

Rattlesnakes, mountain lions, and bears often get more press, but heat is by far the biggest safety risk in Big Bend. At the moment, the park is under an extreme heat advisory, with temperatures regularly topping 110 degrees in low-lying areas. Conditions vary considerably within Big Bend’s 800,000-acre expanse, which encompasses mountain, desert, and river ecosystems—and in the desert, where the risk is highest, temperatures may range wildly during a single 24-hour period (from, say, in the seventies at night and in the morning to triple digits in the afternoon).

“We typically have about two or three deaths a year,” VandenBerg said. He confirmed that there have been four deaths so far in 2023, two in 2022, one in 2021, none in 2020 (when COVID closures resulted in low visitation), and three in 2019. Though park rangers aren’t informed of the official cause of death each time as determined by the medical examiner, “it is safe to say that the majority of these unfortunate incidents are cardiac-related, or the result of another underlying condition that is exacerbated by heat and strenuous activity.”

As Texas Monthly reported in 2021, the pandemic changed the demographics of who visits state and national parks. More and more travelers were novices who hadn’t spent much time in the wilderness. That led to a higher number of rescues at some parks. VandenBerg says that, anecdotally, he still encounters novice travelers more frequently than he once did. Safety tips that may seem obvious—don’t hike in extreme heat, bring more water than you think you need, do your research before you go—are not always so, if you didn’t grow up spending time in nature. “We really want people to be cautious,” VandenBerg says. “Hiking miles in the desert isn’t for everyone, and that’s okay. Maybe plan several smaller hikes earlier in the day, rather than one long, hot hike.” He encourages everyone to stop by the visitors center upon arrival to speak with a ranger or volunteer. “We’ll talk about it and help come up with a plan for you.”

Similar factors are at play in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, about two hours east of El Paso. Though the 86,416-acre park receives far fewer visitors than Big Bend, Guadalupe Mountains is a bucket list destination for Texans who hope to climb the state’s highest peak. A spokesperson for the park wasn’t available for an interview, but Backpacker.com noted that, perhaps surprisingly, car accidents accounted for three of the park’s five fatalities from 2010 to 2020. The park lies along U.S. Route 62, a highway frequented by commercial truckers, and some of the roads are steep and winding. The park’s most recent fatality took place last month, when a hiker fell off a ledge; four months earlier, on New Year’s Eve, someone died on the Guadalupe Peak Trail in windy, freezing conditions.

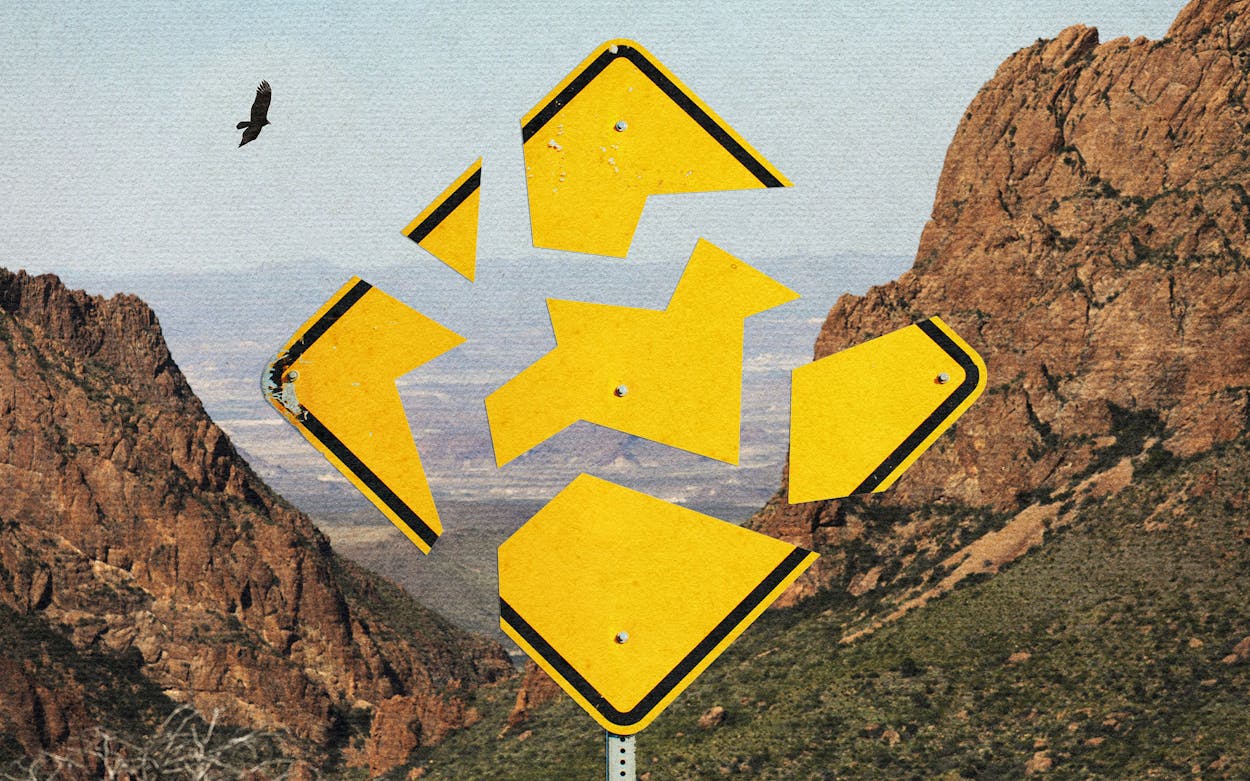

Ultimately, park staff can only do so much to warn travelers away from taking dangerous risks. I asked VandenBerg if Big Bend ever closes trails due to severe heat; he said that it isn’t realistic to do so. “It would actually be pretty much impossible to close the trails and enforce that for day hikers—two hundred miles of hiking trails,” he said. “We don’t have the staff or resources to patrol all of them at all times.” He added that Big Bend doesn’t issue overnight camping permits for low desert trails in the summer, and that many trails already have “abundant signage” warning hikers to turn around if the weather is hot. Marufo Vega, where one of the latest deaths occurred, is among them, in part because it’s an especially remote and risky path; at least three other fatalities have occurred there, as well as numerous other rescues. In January I hiked the Lighthouse Trail in Palo Duro, where one of last week’s fatalities happened, and was struck by the sheer number of safety signs—at least three or four, with glaring all-caps letters and eye-catching colors—at the trailhead, where there was also a water station.

Again, your chances of being seriously injured or killed in a national park are still vanishingly low—probably far lower than the odds of getting in a car crash back home—so don’t let these tragic events scare you away from some of Texas’s most spectacular places. But do let them encourage you to take safety seriously, plan ahead carefully, and never take unnecessary risks. “It’s about not overestimating your abilities or underestimating the desert,” VandenBerg says. “I think that’s a good message: respect the desert.”

- More About:

- Parks & Recs

- Health

- Big Bend