On an otherwise ordinary day, FBI Special Agent Jason Rennie received an extraordinary package. He had been told ahead of time by the U.S. attorney’s office in Plano that it contained allegations of public corruption—a notification he’d never received in his eleven years with the agency. So, when he arrived at his office, in Frisco, to find a standard FedEx box waiting for him, he was especially curious. Sitting in his brown cubicle, he emptied the contents onto his desk: DVDs, USB drives, and some paperwork. After a few preliminaries, he inserted a disc into his computer, settled in, and pushed play.

The video had been taken in what looked to Rennie like a small hotel room, complete with a wall mirror and a window with a decorative shade. On one side of the room, two men and two women were crammed behind a small table; on the other side, a stocky, Spanish-speaking man with close-cropped hair, dressed in jeans and a polo shirt, was seated on a double bed. Every so often, a loud cheer erupted from outside the room. Rennie didn’t understand Spanish, but gradually he realized that the racket didn’t sound like anything you’d hear at a hotel. “Then it dawned on me: they’re in a prison,” he said. As he would later confirm, the man on the bed—who did not appear pleased—was a prisoner.

As his investigation continued, Rennie learned the specifics: that the video, which he received in March 2016, had been shot at La Picota, a prison in Bogotá, Colombia, where many of the country’s incarcerated drug traffickers are held in a luxury area with a soccer field (hence the cheers), and that the man on the bed was Segundo Villota Segura, the leader of a billion-dollar drug manufacturing enterprise until his arrest in 2013. As an FBI translator’s report for Rennie explained, Villota was complaining that he’d paid someone $1.5 million to bribe public officials and that he seemed to have nothing to show for it.

In response, one of the people at the table, an older gentleman with a slight hunch in his shoulders—a private investigator named Chuck Morgan, Rennie later learned—assured Villota, “I paid four people, thanks to you. I was able to pay four people in Washington, D.C.”—and, he also noted, a fifth person, in Ohio.

A few minutes later, the other man sitting behind the desk, who had the deep voice of a classic rock deejay, a white ponytail, and a long, white goatee, piped up. “I know he was mad at us,” he joked, referring to Villota, “because he didn’t offer me any Chips Ahoy! chocolate chip cookies.”

Villota, unamused, ripped open a small bag of cookies and passed it to the man, who, Rennie would discover through a Google search, was a San Antonio attorney named Jamie Balagia, also known as DWI Dude, or just “the Dude.”

The Dude munched on a cookie, then lowered his voice. “By doing it the way we’re doing it . . . it gives me the ability to close my ears sometimes if I need to,” Balagia explained to Villota, pressing his fingers to his ears, “and it protects all of us.”

Rennie had never seen anything like it. A trim and tidy white-collar crime investigator who’d grown up in Texas, he was part of a fellowship that gazed upon boxes of bank records with paternal affection and believed a glass of wine was best paired with a few hundred seized emails. He worked on Ponzi schemes, mortgage fraud, health care fraud—cases he usually developed as spin-offs from other cases, through cooperative witnesses. But this was highly unusual—a potential U.S. public corruption case documented on video—and it had come to him out of the blue.

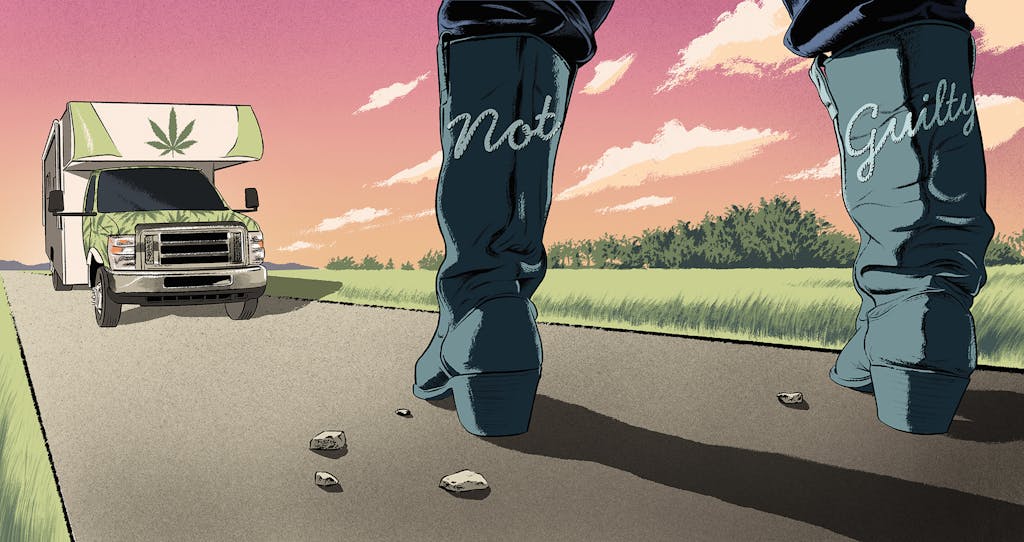

Rennie’s web search revealed Balagia to be an eccentric choice of attorney. When the Dude wasn’t paying visits to Colombian prisons, he was tooling around central Texas in a Winnebago custom-painted with images of marijuana plants and of Balagia himself in a tuxedo jacket, his long, snow-white beard falling over a purple paisley tie. He placed TV ads that ended with him looking into the camera and telling viewers, “Save my number to your cellphone. Now.”

Balagia had further increased his public profile in 2014, when he ran for Texas attorney general as a Libertarian, promoting a “reeferendum” to liberalize the state’s marijuana laws. He even had his own anthem to the tune of “The Ballad of Davy Crockett.” Jamieeeeee, Jamie Reeferman, lawyer of the high frontier.

What, Rennie wondered, was this joker up to in Colombia? The video looked like a scene out of Better Call Saul. “They’re talking about bribing people in Washington. They’re talking about paying people. They’re all acknowledging getting paid. They’re talking about stuff that happened in the past that’s criminal in nature,” Rennie said. “So, it’s very clear that we had at least something to go on.” This was evidence either of a massive corruption conspiracy or of a ham-fisted attempt to defraud a powerful Colombian cocaine manufacturer, mounted by a bunch of idiots.

In person, Balagia exuded mellowness like a marijuana perfume, whether he was walking into a courtroom, a church, or a San Antonio branch of the Mexican food chain Pappasito’s, where he was a frequent presence. Often dressed in a bolo tie and cowboy boots stitched with the phrase “Not Guilty,” he’d flash “Hook ’em, Horns” signs for photos and bestow warm greetings in his resounding, raspy baritone: “Hey, cuz! What it is!”

Balagia was born and raised in Austin, the third of five kids. As he told me during a series of phone conversations, emails, and letters over the past year, his mother was a homemaker, and his father supplemented a state job with night shifts as a convenience store clerk; they lived what Balagia called an “upper lower class” life. In high school, Balagia worked at Safeway after school and drove a baby-blue 1965 Mustang from party to party. “We loved to dance away our weekends to KC and the Sunshine Band,” he said. He started as cornerback for the then-powerhouse Reagan High School football team in 1973 and made it to the state championship game at the Astrodome, where he faced off against a young Earl Campbell.

After graduating from Southwest Texas State University with a degree in criminal justice, he joined the Austin Police Department in 1979 and worked his way to the undercover vice unit. But the vices proved alluring, and in 1988 his colleagues busted him for snorting cocaine and smoking weed, leading to a suspension. After he went through treatment, he was assigned a desk job.

If the Dude was blessed with a single gift, it was unwavering optimism. At age 31, he decided to turn his life around. He found Jesus, kicked drugs, got married, and entered law school at the University of Texas at Austin, finishing in 26 months. In addition to having two children of his own, he looked out for two stepchildren and other family members. “My father passed away when I was ten, and so he was in that father-figure position for me,” said Balagia’s nephew Vincent Balagia, who tagged along on family vacations. The Dude also made a point of welcoming people who were no relation at all. When she was growing up, his daughter, Kalista Balagia, recalled, “Our house was like this safe place for people who would otherwise be transient, for lack of a better word, people who were going through battles or personal struggles. I remember random strangers being invited to Thanksgiving, and I’d be like, ‘What is going on here?’ ”

In 1993, after the Austin American-Statesman published an article about Balagia’s newly established criminal defense practice headlined “Trading Badge for Briefcase,” the clients came pouring in. At first, he took all kinds of cases, but he found he was so repelled by violent criminals that he didn’t want to defend them. He made a list of the kinds of clients he did want: people he would choose as a neighbor, who would help his wife fix a flat tire on the side of the road. The result pointed him in a direction. “We are now going to focus on DWIs and marijuana possession,” he told his staff.

His employees predicted a misdemeanor practice would go bankrupt. But Balagia “was a marketing genius,” said his firm’s office manager, Stacy O’Brien. “He’d always come up with the weirdest stuff, and we’d laugh at him and go, ‘Oh my God, that’s ridiculous!’ And all of a sudden, it’s a huge hit.” He had the company vehicles wrapped with the firm’s phone number, his own face, marijuana leaves, and the phrase “Busted? Call the Dude!” He

advertised on radio and television, telling listeners and viewers to decline Breathalyzers and blood tests. He explained how to handle DWI arrests in interviews posted on Alex Jones’s Infowars website, and he sponsored such events as a Cheech and Chong performance, MarleyFest, NORML gatherings, and the Dude Fifty-Mile Race, where his “Dudettes” passed out DWI Dude T-shirts, lighters, rolling papers, koozies, and playing cards. “My one hundred percent hemp rolling papers were the bomb—everybody wanted those,” he said.

It wasn’t long before the Dude became a local celebrity. Standing in line at the movies or the grocery store, strangers would ask him, “Are you the Dude?” They’d smile at his “weedmobile” heading down the road, or they would honk, take photos, and even hold up their joints, “smiling like crazy,” he said.

By 2005, Balagia had such reach throughout central Texas that he opened a San Antonio office, closer to Cornerstone Christian Schools, which his children attended. As in the Austin office, San Antonio staff members would bond by watching the latest Standardized Field Sobriety Test videos, in which a client might attempt ballet for the officers and then ask them for hugs. For his Christian employees, Balagia offered Scripture readings and conducted a weekly Bible study. Between the two offices, Balagia eventually counted nearly twenty employees.

He was a people person, and a boisterous one at that. “He’s just loud,” said June Gonzalez, a paralegal who worked in Balagia’s San Antonio office. As a single mother of two and a Christian, she appreciated the office’s family atmosphere and Balagia’s faith. “He walked into the courthouse and his presence was known because he would say ‘hi’ to everyone. ‘Hey, how you doing?’ Like he’s running for mayor,” she said. His colleagues admired the way he tried to help all sorts of people he met. “We used to tease him all the time that he had to have some sort of ‘project,’ ” said O’Brien. “It could be another lawyer. It could be somebody at church. It could be somebody he met at a restaurant.”

One project was Jack Pytel, a middle-aged former attorney who had surrendered his legal license and spent nine months in prison after pleading guilty to bribing two San Antonio city council members on behalf of a client in 2004, when he was 58. (The two city council members also pleaded guilty.) Balagia hired Pytel as a private investigator. “I give everybody a second chance; that’s what I’ve always believed in,” Balagia told me. Pytel behaved like a member of the Rat Pack: smoking, drinking, and telling jokes in the company of high-powered attorneys. “Jack was kind of like an older cousin or an uncle kind of a guy,” Balagia told me. “I mean, he might not be the best guy to write an appeal, but he’s the best guy to take the prosecutor out for drinks and, all of a sudden, your guy’s getting probation.” He adored Pytel, even if some of his colleagues didn’t. (“He was annoying, squirmy, a slimeball,” said Gonzalez. “He was really full of himself.”)

By 2010, the DWI Dude firm had become a recognized force. “I was getting not guilty verdicts in cases where everybody said, ‘There’s no way you can win this case,’ ” Balagia said. He says he took forty to sixty new cases each month, mostly misdemeanor cases with a $6,000 retainer. Some years, he says, the firm brought in close to $3 million—$200,000 of which belonged to Balagia. In Manor, just east of Austin, he’d built a four-thousand-square-foot, two-story residence with columns, a terra-cotta roof, and a pool; in North San Antonio, he owned a three-thousand-square-foot home.

Still, he had his worries. His legal strategy often depended on clients who had refused to take Breathalyzer or blood tests, just as he had advised in his ads. But states had begun passing “no refusal” laws that required those stopped for DWI to submit themselves to such tests. Such a law would mean fewer easy wins for Balagia. Although Texas hadn’t yet passed such legislation, “we had all been concerned,” he told me. “We were looking at the end of our golden goose.” While Balagia realized he needed to diversify, he still didn’t want to take on cases involving violent crimes. He didn’t want to downsize, either; he loved his employees too much. He needed a plan B.

One day, Pytel told Balagia that a friend of his might be able to help him out. But it would require going big.

From his office in Frisco, FBI agent Rennie couldn’t figure it out. For all Balagia’s worries about the changing DWI landscape, “just looking at his financials, he was doing very, very well.” Why would he risk involving himself with Colombian drug traffickers?

Initially, Rennie may have overlooked the obvious: Balagia was pushing sixty, and a big score could fund his retirement. Maybe more important, Balagia was seduced by the promise of adventure and the prestige of an international drug case. “Ego played into this, I’m ashamed to admit,” he later testified. Didn’t he deserve a shot at the big time? He may have marketed himself in a humorous way, but he believed his legal skills were no joke.

Balagia was working in his San Antonio office one day when Pytel brought by an old pal of his named Chuck Morgan, whom Pytel had met years earlier, when he was working for the Bexar County district attorney. Originally from Pennsylvania, Morgan was a private investigator with sharp cheekbones and a receding hairline who wore boots and a cowboy hat. Like Pytel, Morgan inspired strong reactions: Balagia drank up Morgan’s tales of risk and danger, while some women in the office thought he was in love with the sound of his own mangled language.“Chuck would say ‘where the tire meets the road’ or ‘where the tire hits the street’—always just a little bit off on every saying,” Balagia said.

Morgan told Balagia he was making Colombia a better place by ridding it of traffickers. Yet he seemed to like hanging out with them.

Morgan told Balagia how he’d worked as a pilot for the CIA during the Vietnam War and then for the Drug Enforcement Administration. In the early seventies, he said, he went to Colombia to set up his first sting on a load of marijuana. He told Balagia he continued working drug investigations in Colombia for thirty years, acting as an undercover operative for the DEA, and eventually buying a house there and marrying a Colombian woman, Adriana, who sometimes worked with him on cases.

Still, he remained a bit of a mystery. Morgan would tell Balagia how great it was to be “back in the game”—a phrase that Balagia never examined too closely. Best he could tell, Morgan had been active as an undercover operative from 1970 to 2000, then took a decade-long break before starting back up as a private investigator. (During later trial testimony, Rennie acknowledged that Morgan had worked with the feds at some point in an undercover capacity.)

Morgan told Balagia he was making Colombia a better place by ridding it of traffickers. Yet he seemed to like hanging out with them. He showed off photos of himself with Pablo Escobar or other traffickers such as the Ochoa brothers, and he would brag about his homes in Florida and Colombia and a two-hundred-acre ranch in Boerne. Balagia was impressed—seduced, even—so he didn’t spend much time pondering whether the hobnobbing with narcos and the boasting were part of Morgan’s deep cover or a sign of unresolved contradictions. Once Morgan offered him a way to get in on the action, he was all ears.

As Morgan explained, when an accused trafficker hires an attorney from the U.S. for an extradition case, that attorney usually travels to the country and sits in while the client is interviewed by federal prosecutors. If a client decides to cooperate—and typically they do—they are extradited to the U.S., where their attorney negotiates the best deal in return for their cooperation. Balagia had no experience with international cases of this sort, but Morgan made the job sound like a cakewalk. He described the attorney’s role as that of a mere coordinator. “You’re really just a chimpanzee,” Balagia said. “You tell the client what the U.S. is offering. It’s take it or leave it.” (Adriana Morgan, Pytel, and Chuck Morgan’s attorney did not respond to interview requests.)

Morgan outlined his plan: he would attach himself to suspected Colombian drug traffickers and persuade them to hire Balagia as their U.S. lawyer. From his Colombian contacts, Morgan would purchase the names of coconspirators and provide them to the DEA in exchange for reduced sentences for Balagia’s clients. If those coconspirators were indicted, Morgan would reach out to them in turn to offer his services. In this way he would develop what Balagia called a “self-perpetuating machine of money.”

“Chuck said the big boys were paying two million each or more for plea deals,” Balagia told me. (In fact, that was the high end of the pay scale, for the most difficult cases.) “I can do a plea deal as well as anyone else, and if Chuck is helping give the clients tradable information, then the clients are happy, the feds are happy, and I’m happy.”

Balagia assumed Morgan knew what he was doing—or, at least, that he had swagger and his wife had powerful Colombian friends. He made it seem as if he just needed a warm body with a law degree to make the scheme work. “He knew I didn’t speak Spanish,” Balagia said. “I’m just this replaceable cog.” Well out of his depth, Balagia decided to trust Morgan.

Morgan already had a prospective client lined up, someone who would make it easy for them to test the business relationship, as the trafficker was not yet under indictment; he was looking for a way to retire from the business without losing all his assets. In 2010 the Morgans, Balagia, and Pytel flew to meet with the prospective client in Medellín, and Morgan made sure to imbue the trip with the same drama as his stories. The four of them had dinner at the home of Escobar’s sister, Maria, whom Adriana Morgan had befriended. According to Balagia, after driving past the guarded entry, the group was escorted onto the elevator that went only to Maria’s floor, where Chuck Morgan showed Balagia and Pytel the bulletproof windows that had been installed after the originals were shot out. The windows were open.

“Is the danger over?” Balagia asked Maria’s new husband. “No, there are still death threats,” he said.

Balagia stepped away from the windows.

As they traveled throughout the city, Morgan pointed out rooftop lookouts who he said were monitoring the group’s movements. He told Balagia and Pytel the city was so dangerous that they shouldn’t wear any jewelry; crime wasn’t as bad as it had been in the eighties and nineties, but after a few years of peace, turf battles were on the rise. Morgan instructed Pytel and Balagia not to leave their hotel under any circumstances without him, but the pair couldn’t resist sneaking out to a casino. “Chuck threatened to send us home and pull us off the case,” Balagia said. “He and Adriana became full-time chaperones for the rest of the week there—boring!”

Finally, it was time for the meeting, in the hotel’s cocktail bar. The prospective client arrived with a group of bodyguards and other associates. While he spoke with Pytel and the Morgans in Spanish, Balagia, not understanding a word of it, watched the TV above the bar. Hopeful as he was, he couldn’t tell whether the meeting went well.

When the group got back to the States, Morgan told Balagia and Pytel that the client had decided to wait to hire a lawyer until he was arrested. But, Morgan said, if a Texas client ever came his way, he’d call them for the job.

After that, Balagia didn’t hear from Morgan for a few years. He continued promoting himself and argued for marijuana legalization as the Libertarian candidate for attorney general in 2014. The San Antonio Express-News described him as looking “like a cross between a ZZ Top roadie and a contestant in a late-period Howard Hughes look-alike contest.”

In August, three months before the election (in which he would receive 2 percent of the vote) he got a phone call. “We want to interview you for a job,” Morgan told him. “I told you I was going to get a Texas case sooner or later.”

The client was Hermes Alirio Casanova Ordoñez, a.k.a. Megatron, one of Colombia’s top cocaine traffickers. Unlike his namesake Transformers villain, this Megatron was known as a courteous and reasonable businessman. “Mega seemed like a really nice guy, but uneducated and grew up in a farming village. He was always polite and cooperative,” Balagia said. Associated with a large crime ring that had been targeted by the feds since 2010, he had been indicted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Texas on drug trafficking charges. Though he hadn’t yet been arrested or extradited, he was looking for an attorney.

Unsurprisingly, the DWI Dude was not his first choice. The Colombian had interviewed a North Texas attorney named Don Bailey, who regularly handled extradition cases and who’d set a typical charge of $180,000. But Bailey told me Megatron wanted something he couldn’t offer. “He wanted to know what I could do to make the case go away—you know: who could be paid off? Because that’s the way they do things in Colombia,” Bailey recalled. “I said, ‘You can’t do that in the U.S.; that’s illegal.’ ”

When the prosecutor in the case, Assistant United States Attorney Ernest Gonzalez (no relation to June Gonzalez), asked Balagia how he came to be hired, Balagia said, “I guess the guys awaiting extradition down there are just thumbing through the phone book.” (Balagia was “being a smart-ass, as I am wont to do in situations like that,” he told me.) In fact, Morgan arranged for Balagia to meet Megatron’s Colombian lawyer, Bibiana “Bibi” Correa, at a hotel near the San Antonio airport, having led her to believe that Balagia had good connections. For their fee, Morgan said, the trio would need $700,000 from Megatron, with $350,000 as a down payment.

The case was hardly standard fare for the DWI Dude’s office. Just before his first trip to Colombia to meet with Megatron, in October 2014, Balagia talked with Gonzalez. The prosecutor knew Balagia was inexperienced and reminded him to get a license from the Office of Foreign Assets Control, which would allow him to accept payments from accused drug barons. But for some reason, Balagia never applied for the license—even though Gonzalez would later remind him again. “Bottom line is, I failed to do due diligence,” Balagia told me. “I stepped in with a half-assed approach.”

Perhaps he’d been distracted. In November, not only did he lose badly in his campaign for Texas attorney general, he also was handed a six-month suspension by the State Bar of Texas. Back in 2011, he had represented a woman after the DEA seized $50,000 from her car. Unable to prove that she’d come by the money illegally, the agency returned the $50,000—which then somehow wound up sitting in Balagia’s office bank account for months.

Megatron was arrested in December, and the following month the U.S. attorney’s office sent a terabyte of discovery evidence, which June Gonzalez had to translate. “It was a lot of work,” Gonzalez said. She wasn’t sure why the practice was taking on such a complicated case, but she kept her opinions to herself. She reviewed recorded phone calls, read through records of intercepted deliveries, and matched the records with photographs of labs and semisubmersible watercraft that were used to transport illegal drugs.

Just as Morgan had hoped, the Megatron case wasn’t their only federal case for long. Others in Megatron’s crime ring heard about Morgan (“El Gringo”), including Villota, one of two brothers who went by the nickname “Los Corticos,” or “the shorties,” as they were both about five foot three. In 2013, when they were arrested, Los Corticos were regarded by the DEA as the largest producers of cocaine in Colombia. Along with Megatron, they had been indicted for distributing large amounts of cocaine from labs in the mountainous jungle region of Cauca. Morgan and Balagia agreed to take Villota’s case, charging $900,000, asking for half of the money up front.

The fees started to roll in. Between September 2014 and May 2015, Megatron’s lawyer, Correa, paid in installments that often arrived as cash in paper bags. Once, June Gonzalez and Balagia drove to a mall parking lot in Houston, where a middle-aged man they had never met dropped a shopping bag on the back seat filled with nearly $80,000. Gonzalez called the interaction “businesslike—like, ‘Hey, this is for the attorney.’ ‘Thank you.’ ”

By the end of 2015, Gonzalez, who had spent much of that year reviewing and translating the incriminating documents and recordings that prosecutors had provided, had concluded that the evidence was overwhelmingly bad for Megatron and Villota. “We’re toast,” she told Balagia. A cartel bookkeeper had become an informant. “The bookkeeper kept handing over the phone numbers every time they would change [them].” For years, Balagia said, every one of their conversations had been wiretapped.

Nonetheless, for a long time Villota maintained high hopes—too high, he eventually realized. In December, Morgan called Balagia and said there was an emergency; they had to go to Colombia right away. “This is top secret! We need to have a meeting! No one can know about this! We need to discuss it! Mum’s the word!” Balagia said, imitating Morgan. “I’m like, ‘Huh?’ Why don’t you just say I need to talk to you? . . . He was the drama king of the universe.”

It turned out Villota had complained to Morgan that he had paid top dollar but was still under arrest. He was beginning to wonder if he’d been ripped off.

Federal investigators believe that Balagia, Morgan, and Correa had offered to bribe officials. “Segundo [Villota] wasn’t asking about bribery out of thin air,” Rennie told me. “He was given assurances that things were going to happen.” Apparently feeling that Morgan and Balagia were taking advantage of his situation, Villota decided to secretly record their meeting and send the video to the FBI.

By then, Balagia says, he felt like he was on a sinking ship.

Members of the group tell different stories about what happened in Villota’s cell that day. Correa told me that they decided to lie just before they met him at La Picota and tell him what he wanted to hear—that the legal team was greasing palms—in order to buy themselves time. Balagia remains adamant to this day that the first time he heard about bribery was in the cell at La Picota.

But in the video of the meeting, Balagia doesn’t seem to bat an eye when Morgan mentions paying bribes. “I’m sitting there . . . I hear [Adriana] say to Chuck something like, ‘He wants to know about the guys you paid off in Washington, in D.C.’ And I’m like, ‘What did I just hear?’ You know, this is weird.

“Why didn’t I immediately jump up and go, ‘What are you all talking about? I’m not party to this.’ I wasn’t gonna jump up and say squat. As a matter of fact, if you look at me, I didn’t even move.” He says he found Villota intimidating. “Hard, hard-core. Like this guy would have you hit. Without a doubt. And very aggressive and loud and threatening. . . . And I’m just, ‘Hey, man! I’m a lawyer!’ You know?” At his trial, Balagia insisted that he was just playing along in a tense situation. “Chuck was the boss,” he told me. “I accepted it because I was getting paid a lot of money.”

Balagia swears that after the meeting, he confronted Morgan about the bribes and that Morgan told him it was a story Correa had told the clients. “He goes, ‘Down here, if the best lawyer in the nation says, “I’m going to fight all these constitutional laws and I’ve got a big team and blah, blah, blah,” and the next guy walks in and he can barely keep his pants on, but the guy goes, “I’m gonna bribe the judge,” guess who gets hired? This is the Colombia way.’ ” Balagia says he threatened to report the deceit to Ernest Gonzalez, but Morgan told him the information could put them all in danger. If word got back to the clients, Morgan said, they would kill Correa and her husband and baby, they would kill Morgan’s wife’s family, and then they would come for Morgan himself.

Balagia thought about this. Surely, he figured, the clients would take their plea deals and conclude that bribes were a contributing factor in their reduced sentences. How would they know they’d been lied to?

What Jason Rennie saw in that prison video was a man in over his head: “Balagia was a cat on a hot tin roof. He was not comfortable. He was looking around. I think he was looking for cameras. I think he kind of in the back of his mind thought, ‘I don’t need to be here. This is not a good situation.’ But after [Villota] paid these people over a million dollars, you don’t really say no to him.”

During the investigation, Rennie pored over financial statements and other records, on the trail of the money that Correa had sent north. After months of searching, he concluded that none of that money had been deposited into the accounts of any government employees involved in the Villota case. No one had been bribed.

Having ruled out public corruption, Rennie turned his focus to Balagia. What he found was intriguing. “People’s whole lives are on their credit cards, and their banks, and their phone records,” he said. “You can put that in the time line, and you’ll know everything you ever wanted to know about somebody.” Between September 2014 and May 2015, Rennie determined, Balagia was depositing funds into a rarely used personal account. Suddenly it was flush with cash deposits—and, significantly, each deposit was less than $10,000, the threshold above which cash transactions must be reported to the IRS. What’s more, Rennie discovered, Balagia hadn’t gotten the required license that prosecutors had told him he needed to obtain from the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Without that license, he couldn’t legally take money from suspected drug traffickers.

The ATM portion of the scheme was remarkably sloppy. According to prosecutors, multiple coconspirators deposited nearly $175,000 into Balagia’s account through ATMs in seven states—sometimes at institutions two blocks from each other, with only thirty minutes between transactions. To Rennie’s mind, the huge amount of money paid to Balagia suggested that he had promised his clients something big.

And that promise pointed toward a crime. Villota had been cooperating with the DEA, then stopped after Balagia entered the picture. “I had no reason to believe that [Villota] wasn’t wanting to cooperate, that he wasn’t wanting to talk to us,” Ernest Gonzalez later testified. “He told us . . . that he did. He had provided us information already.” The cause of the delay, the feds surmised, must have been Balagia, and if an attorney prevents a client who wants to cooperate from doing so, they are potentially committing an obstruction of justice.

But before anyone could be arrested, Rennie needed to corroborate what he’d seen on the La Picota video and catch Balagia in some overt act—and this is where he had great luck. By chance, Villota’s brother, Aldemar Villota Segura—the other half of “the shorties”—was being held at the Collin County Jail, in McKinney, only eighteen miles from Rennie’s office. Indicted along with his brother and Megatron, he’d been extradited and was working with a different legal team to negotiate his plea. “That was definitely convenient,” Rennie told me. “And so we started to think, ‘Okay, is there a way that we can do any proactive evidence collection?’ ”

Soon enough, Rennie found himself sitting across a table from a mild-

mannered Colombian man with a square head, a thinning mustache, and puffy eyes. Aldemar was an articulate and commanding businessman who was leery of his brother’s lawyers. “I told my brother these people were ripping him off,” he said to Rennie. “He’s a fool to give them any more money.” Then he told Rennie he was game to be a decoy.

They’d have to be careful. Balagia seemed to be growing increasingly nervous, as though someone had tipped him off that he was under investigation. In May 2016, he tried to head off a possible accusation by bringing up the topic of bribery in a meeting with Ernest Gonzalez. For some reason, Balagia told Gonzalez, his client seemed to be under the impression that part of his fee was going to bribes—specifically, that $200,000 or $250,000 was going to pay off Gonzalez. Well aware of the investigation into Balagia, Gonzalez played along. “Oh yeah, like I’m that cheap,” he said, laughing.

“Do you believe, in this case, that you are the brains behind the operation?” Riddles asked him on the stand. “Maybe a birdbrain,” Balagia replied.

Cautiously, then, as part of the sting, Aldemar asked Balagia to represent him, and in November 2016, Balagia, Morgan, and June Gonzalez met with him in a conference room at the Collin County Jail, along with a woman who introduced herself as his accountant and interpreter—actually a wired undercover FBI agent.

Aldemar insisted on clarifying his terms, per his instructions from the FBI, even as Gonzalez explicitly mentioned that she always worried about recording devices in jailhouse conference rooms. Aldemar was okay with a $1.2 million fee, he said, adding, “The money is drug money.” Rennie listened closely as Balagia responded that he could fill out some paperwork to accept the drug money, a position at odds with the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986. (An OFAC license allows an attorney to work with international drug traffickers on a designated list, but the fee paid is not supposed to come from drug proceeds.)

Next, Aldemar raised the possibility of bribery. “My brother [paid] one and a half million dollars, and nine hundred thousand were paid to some people in Washington, D.C.,” he said. Rennie noticed that the group looked nervously around the room and seemed to go out of their way to downplay this incriminating arrangement. Morgan explained that he had secured help in Washington, and sometimes that had cost money—“maybe an extra scoop of ice cream on a sundae,” he said—but no one, he emphasized, was making any promises.

Undiscouraged, the female undercover agent pushed for confirmation after the meeting ended. Outside, as Balagia, Morgan, and Gonzalez were saying their goodbyes in the parking lot, the agent reiterated that Aldemar wanted the money used efficiently. “You understand what he’s looking for, right?” she asked. “His understanding is basically like this money is going to the right people to get him off the charge. And that’s what he’s looking for, that’s . . .” she trailed off.

“It was nice meeting you,” Balagia said, excusing himself abruptly.

Morgan, though, played it cool. He flirted with the undercover agent as he walked her to her car. “You’re a pleasant surprise!” he said. “I was expecting some big old guy, you know? Guns in their hands.”

The agent laughed. “Oh, I know. Nowadays, we go unnoticed. It’s the best thing.”

Then Morgan addressed her concern about Aldemar’s “understanding”: “I don’t have a problem with one word he said.”

“Uh-huh,” the agent said. “Okay.”

“Where in the States would you be wanting to deliver?”

By then, Balagia says, he felt like he was on a sinking ship. He had the unnerving sense that he was being watched and that the fantasy of becoming an international player might be evaporating. Then there were money issues: a Colombian associate of Correa’s, who’d taken Segundo Villota’s payment, had overcharged the drug trafficker by $600,000 and shaved off that amount for himself, only to be kidnapped until the money was returned—an unsettling reminder of the type of characters who were in the mix. And Megatron had yet to pay the remaining $350,000 of his fee. “Paga todo,” Balagia told Megatron, pushing him for the remainder. “Money talks and bullshit walks.” If Megatron didn’t pay, Morgan said he wouldn’t hand over the thirty names required for reduced sentencing. “Chuck’s going, ‘I’m not gonna to give it,’ ” Balagia said, “and I’m crappin’ my pants going, ‘Then why am I even here?’ ”

Balagia says he just wanted to be done with the cases. “I was so fed up with everything, I was just like, ‘Whatever,’ ” he told me. “Let’s just wrap the three of them up, get them the best deal possible, let them go do their five to ten years, and kick their butts down to Colombia, and I never have to hear another word about them.”

If he only knew how soon he’d be done with them. Two weeks after the meeting at the jail, Balagia, Morgan, and Gonzalez piled into Balagia’s black Mercedes SUV, decked out with marketing for the DWI Dude, and drove to the agreed-upon location for Aldemar’s cash pickup: an Asian fusion restaurant in Grapevine called Lava 10. From a room at a nearby Comfort Inn, the FBI surveillance team, including Rennie and a few other agents, were monitoring the undercover agent’s transmitter.

For once in his life, Rennie thought, he wouldn’t have to wonder what car the suspect was driving.

Morgan got out of the SUV and walked into the restaurant, where the undercover agent directed him to the parking lot out back. There, a colleague handed over a bag full of cash. No sooner had Morgan accepted the payment than agents arrested him and whisked him to the Comfort Inn for questioning.

But in the middle of the operation, some confusion occurred. In an adjacent lot, a car driven by an FBI agent pulled in front of Balagia. Although the agent’s instructions were just to block Balagia’s view of the arrest and help make sure the government got its $300,000 back, he misunderstood his assignment.

He jumped out of his vehicle and aimed his gun at Balagia. “Don’t move! Don’t move!”

“Hey, man,” Balagia replied, “I’m not doing nothing.”

“Who are you?” the agent asked.

Balagia pointed to the image of himself on his car.

The agent contacted Rennie, realized his mistake, and cut Balagia loose, giving no explanation for his actions. “He just runs back in his car, starts his car, and drives off, and leaves me sitting there. And I’m like, ‘What in the world is going on?’ ” Balagia told me.

But now Balagia knew the FBI—or somebody—was watching. “All of a sudden, Chuck’s just missing, and I’m like, ‘Oh God, did the cartel get him or did the feds get him?’ ” Balagia said. “I was trying to call Chuck like crazy. And then I tried to call Ernest Gonzalez . . . and the DEA agents who were working the case, because I was like, ‘Look, I don’t know if Chuck’s been arrested or if he’s been kidnapped.’ ” All but one of his calls went straight to voice mail. The only person he reached, a DEA agent, denied knowing anything.

All the way home, he kept asking June Gonzalez, “What did Chuck do?”

Rennie understood what would happen next, and on some level, it seemed Balagia, who eventually realized that his business partner was in custody, did too. A few weeks after Morgan’s arrest, Balagia told his office manager that he’d be going with June Gonzalez to meet with Megatron at the jail where he was being held in McKinney. The office manager asked, “Are you staying overnight or coming right back?” With a laugh, Balagia replied, “I don’t know. Maybe I’m going to get arrested.”

In fact, as soon as Balagia’s wife dropped him and Gonzalez off at the Collin County Jail, two men came walking toward them. “Are you James Morris Balagia?” one officer asked. Balagia said, “Yeah, that’s me,” and handed Gonzalez his cellphone and wallet as he was handcuffed.

At trial, where he was charged with money laundering, obstruction of justice, wire fraud, and violation of the Kingpin Act against international narcotics trafficking, Balagia tried to play dumb. After the government froze his assets, his court-appointed attorneys, Gaylon Riddles and Matt Hamilton, argued that Morgan was the ringleader. Balagia was in over his head, they said, a “hippie” and a “hillbilly” who drove a “Scooby-Doo van.”

“Do you believe, in this case, that you are the brains behind the operation?” Riddles asked him on the stand.

“Maybe a birdbrain,” Balagia replied.

It was hard to argue with that. Nonetheless, the prosecution countered, he’d deposited $475,000 into his bank accounts. Much as he might try to blame others, Balagia had failed to file for an OFAC license, failed to file IRS paperwork, and picked up drug money in cash. He’d obstructed justice by impeding Segundo Villota from cooperating with prosecutors. And in meetings that had been recorded, associates had made comments about bribery, and he never took exception to that line of discussion—except near the end, when he seemed to suspect that he was being monitored as he met with Aldemar.

Megatron, Correa, and Morgan—who ostensibly developed dementia sometime after his arrest—all pleaded guilty and testified against Balagia. (Adriana Morgan and Pytel were not indicted.) Balagia was found guilty on all counts after a two-week trial in Sherman. In May 2021 the judge sentenced him to fifteen years and eight months at the Federal Correctional Institution at Big Spring, about one hundred miles southeast of Lubbock. Morgan, who received a lighter sentence because of his cooperation, was released in December 2021; Correa is scheduled for release next summer. Megatron will be released in 2037.

“I think Chuck and Jamie had a plan,” said Rennie, explaining his theory of the case. “The plan was: Chuck is going to do all the dirty work, Jamie is going to keep his ears closed . . . and Bibiana is going to take care of the stuff in Colombia. And I think they just let Segundo believe that Jamie had connections that he could exercise in Texas to take care of everything that needs to be taken care of.”

“Everything I did was so stupid,” Balagia told me one of the last times we talked. “I want to kick myself in the butt every day when I think about it. But I fell in under Chuck’s little magic—which is embarrassing to say, because I’m supposed to be intelligent and streetwise and, you know, whatever.” He maintained that he never intended to break the law and is appealing his conviction.

And if the appeal doesn’t work out, he said, “I’ll be smiling and stepping on. That’s where it’s at. I’m kind of like, this is the wildest adventure in the universe. If you read this in a book, you’d go, ‘This is crazy! The author, he’s smoking too much weed.’ ”

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Dude Abides.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Crime

- San Antonio

- Frisco

- Austin