This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

This was what Paco Olivera had waited eight years for. Tomorrow he was to take his alternativa at the bullfight, tomorrow he would cease being a novillero, a novice, and join that select group of bullfighters who have mastered their profession and become matadors. Even the word was like a tonic to him; his face would light up each time he found occasion to pronounce it, savoring the stately Spanish cadence that draws the word out into three distinct syllables: “ma-ta-dor.” He had been waiting for this night since he was twelve, when he had announced his intention of becoming a matador. Now that it had come, his pride knew no bounds.

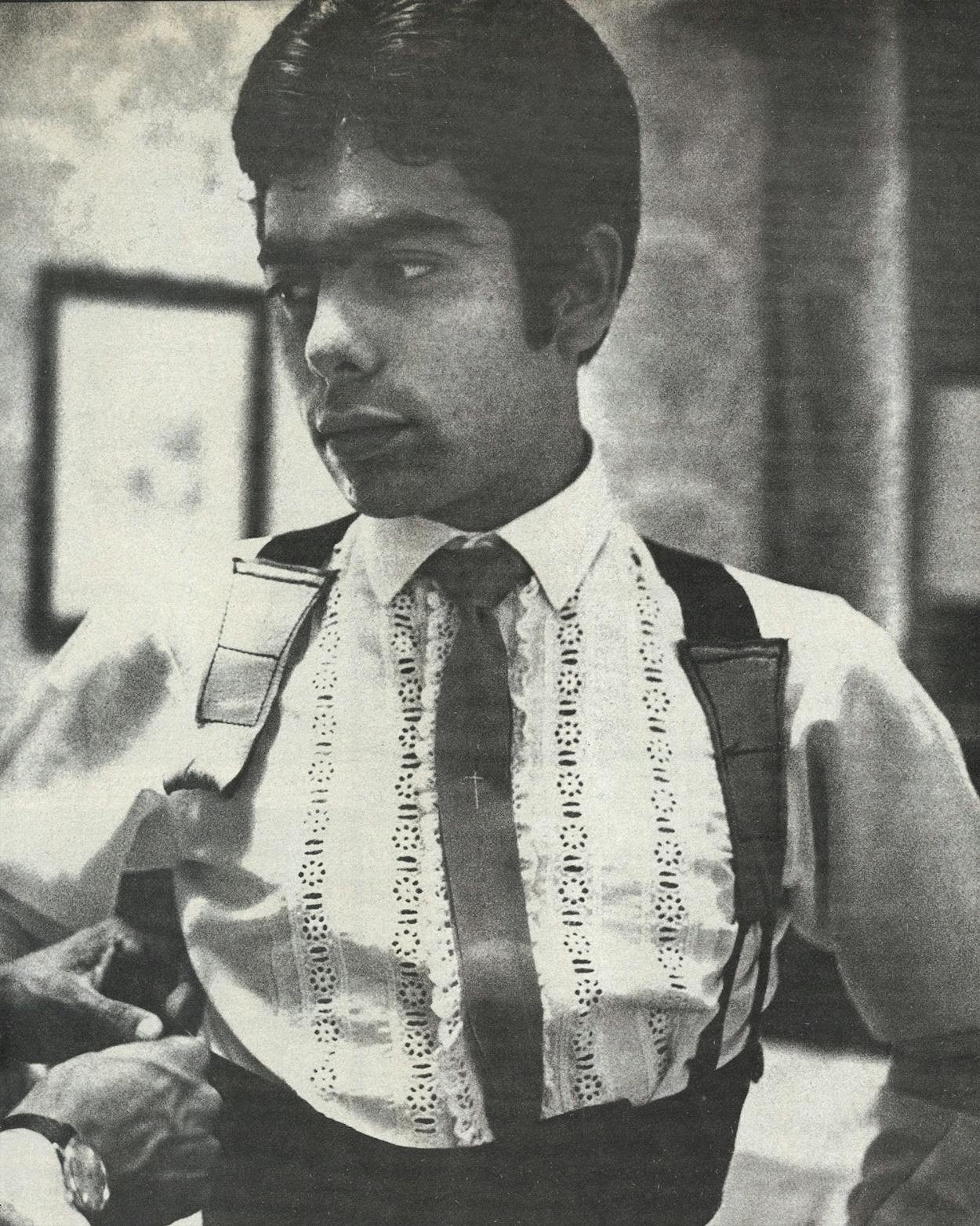

At twenty, Paco is small and, like all bullfighters, extremely graceful. He was sitting at the head of a long table in the brightly lit cafe in Reynosa, flanked by the members of his cuadrilla, the team that assisted him in the bullring. His manager was there, as was his mozo, the personal servant who would act as his sword handler and attend him during the dressing ceremony the next day. There were also several of his novillero friends who had driven up from Mexico City to be with him for this important occasion. They could not quite hide their envy.

Nor could the other patrons of the cafe resist glancing over at the young man sitting so nonchalantly in his chair. Perhaps they did not know who he was, but there is something in the way a bullfighter carries himself, even in the way he holds his head and moves his hands, that announces his identity to the world. Bullfighters are different from American athletes. They are held in a special awe that transcends their ability or their courage. Even the mediocre ones are considered to be in a class above normal mortals, are regarded as a kind of combination of priest and athlete.

“Bullfighters are held in a special awe. Even the mediocre ones are considered to be in a class above normal mortals, are regarded as a combination of priest and athlete.”

Paco was very conscious of this, conscious that this was his time and his alone. It was not important that his alternativa was being taken in an insignificant plaza in the border town of Reynosa rather than in the Plaza Mexico in Mexico City. A plaza such as Reynosa’s does not draw the true aficionados, and the matadors do not put out their best, for they know the fans will not notice, much less appreciate, the finer points of their art. But none of that mattered to Paco. What did matter was that he would be given his initiation by Manolo Martínez, the number one matador in all the world.

Paco had worked hard for the honor. If you were to go down to the Plaza Mexico in the early morning you would see perhaps five hundred would-be novilleros, some as young as ten years of age, working out with their capes just as Paco had. Some would be charging each other, their hands at the sides of their heads to simulate horns; some would be caping the trundle, a two-wheeled cart with a set of horns mounted on its front; some would be working alone, others under the tutelage of retired banderilleros or matadors. Of the five hundred you would see on any given morning, perhaps four or five would actually get the chance to fight a bull as a novillero. And of these, the odds were very good that none would become a full matador.

Paco had fought as a novice since he was sixteen and had killed over a hundred bulls in 68 corridas. Cynics might say that Paco’s rich family had paid Manolo to preside at his alternativa, but Manolo was already about as rich as a bullfighter can get. Besides, it is not good politics for a senior matador to put his stamp of approval on a novillero who will turn out to be nothing. That sort of thing is remembered in bullfighting. Manolo was there because he thought the young novillero had promise.

To make the honor greater still, the number three matador, Antonio Lomelín, would also be appearing on the card. For many aficionados, this was the real draw; since Antonio does not have the technical skills of Manolo, he takes more risks. He is also a more emotional killer when he goes in over the horns.

But as Paco celebrated in the cafe, neither of the matadors was yet in town. They would not arrive until the next day. Paco, of course, had come in early. In fact, he had already been down to look at the bulls. Leaning over the heavy corral fence, he’d studied the six sleek fighting machines, these arbiters of his destiny. The bulls had been advertised at 475 kilos, or a little over 1000 pounds, each. Under Mexican law, bulls under 450 kilos may not be fought in a corrida by full matadors. An impresario who puts on a corrida with bulls under 450 kilos or under the age of four years can be fined or sent to prison. But such an occurrence is beyond the memory of anyone. And certainly the bulls slated for Paco’s alternativa seemed of the proper age and weight. He surveyed them all closely but would not say which he preferred to draw. “No,” he said, “for me that is bad luck.”

At the table that evening an American tourist who had heard that Paco was a matador came over to talk bullfighting. It was the tourist’s first bullfight. He asked Paco if he didn’t feel sorry for the bull. The novillero regarded him with surprise. “No,” he said, “of course not. Does he feel the sympathy for me?” One felt love, respect, affection for a good bull, he explained, but never pity or sympathy. But the man didn’t understand how he could love the bull and then kill him. How did Paco feel when the bull was dead? he pressed. Paco smiled, his white teeth gleaming. “Contento,” he replied.

He was becoming tired of the man, so he didn’t try to explain the corrida further. He knew it was useless: you can’t make someone understand who does not feel it inside. Bullfighting, to Paco, is making art, and art made in the face of death is great art. But he knows that others see only the blood and the suffering of the bull. They think it quite all right for a steer to be hit in the head with a sledgehammer, but they consider it cruel for a fighting bull to be killed with a sword.

“Most Anglos find it difficult to appreciate the meaning of the bullfight because they think of it as a celebration of death rather than what it is—a defiance of death.”

Most Anglos find it difficult to appreciate the meaning of the bullfight because they think of it as a celebration of death, rather than what it is—a defiance of death. According to the Spanish mystique, the bullfighter is the spectators’ surrogate against death. If he enters the arena of his own volition and faces death willingly, then can death be such a terrible enemy? To maintain this illusion, it is very important that the matador face the possibility of destruction with superb grace and disdain. He must work close to the horns; he must take risks. Otherwise there is no point. A cowardly matador who uses tricks and gimmicks and stays well clear of the bull’s horns incites the crowd’s anger; he has defeated the very purpose of the corrida de toros.

But one does not say these things to matadors, or to novilleros who are about to become matadors. They may understand them inside, but they don’t speak of them. Such talk is reserved for philosophers and intense aficionados who feel a need to explain the fiesta brava in terms they can understand.

Certainly no such weighty constructs clouded Paco’s mind as he left the cafe to walk to his hotel room. The only thing he said was directed to his manager. “If I get bull seventy-one [which he had privately decided was the best of the six], should I fight him for my alternativa or save him for last for the crowd?” he asked.

His manager answered, “Let us wait until we get bull seventy-one to decide.’’

As they parted Paco joked, “Now the only thing that can stop me from becoming a matador is if I’m killed in a car wreck on the way to the plaza.’’ And that was true. For he would take his alternativa in the ring before he fought his first bull; even if that bull killed him, he would still die a matador.

Paco slept late the next morning, staying in bed until it was almost time to go to the sorteo, the pairing and drawing of the bulls. It would not take place until twelve-thirty, but Antonio Lomelín, who had arrived that morning, went an hour earlier to look over the bulls. The corral was already swarming with factotums and aficionados. Making his way through the crowd, Antonio was waylaid many times to sign autographs, to talk, or just to exchange greetings. When he finally reached the corral he studied the bulls for a long time. Photographers from the Mexican papers surrounded him, cameras clicking. Antonio is a handsome man, somewhat larger than Paco, but his face shows the strain and fatigue of the sixty to seventy corridas he fights each year.

As the matador watched, his manager threw rocks at the bulls to make them move around so Antonio could study how they carried their heads and thus learn which horn they might favor. (A bull is either left-horned or right-horned, meaning he prefers to hook with that horn. The matador, naturally, will always want to pass him on the other horn.) Antonio liked bulls 71 and 63, just as Paco had.

The sorteo is a very important part of the corrida. Generally, there are six bulls and three bullfighters, so each matador will fight two bulls. A manager would like to see the two best bulls paired so that his matador will have a chance to draw the two best fighting bulls in the corrida. Instead, as a compromise, the managers usually agree to pair the bulls in a best-worst coupling.

The ceremony for assigning the bulls to the matadors has not changed for perhaps a hundred years. A disinterested party takes three cigarettes, empties the tobacco from them, and writes a pair of numbers on each of the papers. Then the managers roll the papers into very hard little balls. The balls are put in a hat and each manager draws for his matador. The president of the bullring stands by to record which bulls each fighter has drawn. Very solemnly he receives the cigarette papers and transfers the bulls’ numbers to the official ledger.

Antonio did not stay for the sorteo; it was beneath his dignity to do so. But Paco was there. He drew bull 71, which had been coupled with bull 37. He and his manager decided that he would fight bull 71 for his alternativa and then do the best he could with bull 37 later.

“I must please the people,” he said. “And I think this is the best way.”

Paco was happy with the draw. Both of his bulls were corniabiertos, open-horned bulls that are less likely to give the matador a cornada, a goring. The other four bulls were cerrados, bulls whose horns point forward, allowing them to inflict more serious injuries. Antonio Lomelín has had sixteen femorals, wounds to the inside of the thigh that pierce the femoral artery. These are the most dangerous wounds in bullfighting—without immediate medical attention a matador can bleed to death in minutes. Antonio has been lucky: all his femorals have occurred in important bullrings that were equipped with an infirmary, where a surgeon was standing by. But there was neither infirmary nor surgeon at the arena at Reynosa.

At five o’clock, in his hotel room, Paco prepared himself for the dressing ceremony. His mozo, Jorge López, had come in to assist him. Paco was nervous. He held his right hand out to judge the degree to which he was shaking. There was a certain tremble, but he was far steadier than one would have imagined under the circumstances.

The ceremony began with Paco going to the small bathroom to shower and wash his hair. Then he returned to the bedroom and sat on the bed to clean his fingernails. He was meticulous, determined to be completely clean when he went into the ring. When at last he was ready to dress, he sat down on the side of the bed with a towel wrapped around his waist. First came the long white understockings. They were silk and required a lot of smoothing before they were exactly right. His mozo secured them below the knees with elastic bands. Next he shucked the towel and pulled on the white linen pantaloons, made in a style almost as old as the bullfight itself. Then came the pink outer stockings, also silk. His trousers were of an elastic material, but even so it was not easy to put them on properly. To get them fitted Paco straddled a rolled-up towel. He held one end of the towel, his mozo the other, and they both tugged and pulled. The pants in particular must be skintight: a bullfighter wants no loose fabric that a horn might accidentally catch. Many people think the pants need to be tight in order to show the bullfighter’s cojones plainly, but that is only a fable dreamed up by tourists.

By now a small crowd was standing against the far wall. Paco’s manager was there, as well as his father and grandfather and a number of the novilleros. But Paco paid no attention to them; it was plain that his mind had turned inward to the two bulls he would face that evening. His mozo helped him on with the ruffled shirt, then wrapped the sash snugly around his waist. Next came the thin tie and the heavy brocaded vest and jacket. The mozo pulled the vest tight and fastened its inner snaps. Paco had to hold his breath like a woman getting into a corset before his servant could make the fastenings come together. After that came the shoes, like ballet slippers, and the black hat, the montera, with lead in it to make it stay securely on his head. The last act was the tying of the tassled strings called machos at the knees of his pants.

Paco was ready. His “suit of lights,” which had been bought by his father for this very special occasion, had cost $900. Normally a bullfighter pays around $600 for a traje de luces. He will wear it, barring mishaps, for six to eight fights and then sell it to a banderillero or a novillero for a couple of hundred dollars. But Paco was not going to sell his suit. It would go into a glass case in the parlor of his father’s house in Mexico City.

The mozo and the peones, as the banderilleros are called, collected Paco’s sword case, muleta (the small killing cape), and fighting cape. His father held the door open for him, and the procession descended the stairs, Paco walking very proudly. His third cape, the ceremonial one, was wrapped around his left arm. In the lobby and in the parking lot several women rushed up to kiss him on the cheek and to wish him good luck. He accepted the affection stiffly, for his mind was now on the bulls. But the kisses were very much a part of the tradition.

In the car Paco was very quiet. A crowd awaited him as he pulled into the back of the arena. Several officious policemen were on hand, but they were ineffective against the throng of people who swarmed toward the suit of lights. With the help of his entourage Paco struggled through the gate to the alleyway that led to the door from which he would make the paseo, his entrance. Antonio and Manolo were already there, their ceremonial capes hung over their right arms. They were laughing and joking with each other and with the aficionados who surrounded them. But they stopped when Paco came up and gave them a formal bow. In turn they each gave him an abrazo, a hug, which in Mexico is much more meaningful than a handshake.

It was now only moments before the grand entrance. Paco went to the little private chapel and knelt before the Virgin. In his room he had prayed for ten minutes in front of his own portable chapel while his entourage stood silent and respectful. Now he was saying another prayer, bending awkwardly in his suit of lights. When he had finished he rejoined Antonio and Manolo, who stood stiffly in front of the gate. Paco was in blue with gold trim, Antonio was in red, and Manolo was dressed from head to toe in gold. Only a matador can wear gold. If a banderillero buys an old suit of lights from a matador he must remove the gold braid.

Outside in the callejón, the space between the barrier and the stands, the impresario, Luis Tamez, stood looking up at the crowd. He was anxious—it appeared that he was about to lose money. There were perhaps five thousand seats, of which three thousand were now filled. At $7 a person, that made his take around $21,000. The six bulls had cost $9000; Manolo had cost $7000 and Antonio $6000. If there were enough left over Tamez would have to pay Paco $1000. But that was highly unlikely. At best, the impresario would break even.

Despite its popularity, the corrida de toros makes few men wealthy. At one time bullfighting served the same function in Mexico that boxing did in the United States: it was a way for a poor boy to get out of the slums. But no longer. Now the novillero’s family must have money to pay for practice bulls and assistants. For four years Paco’s father, who is a rich architect in Mexico City, and his grandfather had paid for his passion. Still, Paco’s chances of earning the kind of money that Manolo and Antonio make are very slim indeed.

As the trumpets sounded, the attendants swung open the gates for the matadors. The trio came walking across the sand of the arena, Manolo Martínez in the middle, Antonio on his right, and Paco, as was proper, walking one step back. Behind the bullfighters strode their cuadrillas. The crowd cheered as they crossed the arena, and the matadors raised their arms in acknowledgment.

All except Paco. By now he was very pale. He came to the barrier and accepted the fighting cape from his mozo. “Agua,” he said in a tight voice, holding out the cape so that water could be poured on it. Then he scuffed it in the sand to make the bottom heavier. A stray gust of wind can blow the cape back against the matador’s body, and the bull’s horns will follow. But he does not want to get the cape too heavy; it can make his wrists numb so that he loses the fine touch he needs to control the bull.

The trumpets blew and the first bull came skidding into the arena. Paco stood behind the barrier and studied the animal while his banderilleros took it through a series of passes. He was watching to see which horn the bull favored, to see how easily he was incited to charge. Paco watched for perhaps two minutes and then walked out into the arena, waving away the banderilleros, adjusting his cape, walking toward bull 71. He took the bull through one pass, the classic veronica that looks so simple, yet requires such skill. Then he motioned to the banderilleros to take the bull away and walked back to the barrier. Manolo came out to meet him. They embraced. It was the moment Paco had waited years for. Manolo said, “Now you are a matador. And I welcome you.’’

“Thank you, maestro,” Paco replied. Then Antonio came out and embraced him. Across the arena the banderilleros were keeping the bull occupied, but no one was paying any attention to them. The senior matadors retired. Paco lifted his montera and, holding it aloft, slowly turned a circle to acknowledge the applause. But he did not dedicate the bull to the crowd. He had reserved that honor for the man who had made this moment possible. His father was sitting in the front row; Paco walked to the edge and pitched his montera to him. Then his father leaned over the high wall and they embraced. The crowd cheered its appreciation of the gesture.

Paco had been mistaken about bull 71. He was not a good bull; he was cowardly and would not charge. Paco did the best he could with the cape, but he could not put together a series of linked passes. The bull would do nothing but make little chopping rushes and then stand panting, staring at Paco. At one point the new matador walked up and slapped the beast on the muzzle—with no effect.

Finally Paco summoned the mounted picadors to shoot the iron point of the lance into the bull’s hump. This is done to make his head come down so that the matador can go in with his sword over the horns. Most matadors are so short and the bulls so tall that if the tossing muscle is not weakened the matador has no chance. But Paco allowed only one blow and a very mild one at that. Then he performed the quite, the use of the cape to take the bull away from the horse.

The trumpets blew for the banderillas, the barbed darts that are thrust into the bull’s shoulders. Many people think they are for goading the bull, but that is not true. They are used to correct his hooking tendencies. If a bull hooks with his right horn, the banderillero places the barbs on the left side to make him more conscious of that side so he will charge straight ahead. This timid bull required no correction, and the placing of the banderillas was an emotionless event.

Paco began trying to work the bull into a kill position. He had taken the muleta and sword from his mozo. The bull would not charge. Paco incited him with the muleta, stamping his foot, but it was no use. The bull had taken up a position against the barrier in his querencia, his turf, and he refused to come out. This is the most dangerous place in the ring to try to kill a bull, for he can simply stand still and hook both ways as the matador comes in over the horns. Manolo, watching from behind the barrier, shouted, “No, make him come away.”

But Paco did not seem to hear him. He walked toward the bull. His face was very pale. The bull just stood there. Paco tried to get him to charge the muleta, but he refused. He stood with his feet spread, a posture that closes the shoulder blades so the sword will not go in. A bullfighter tries to position the bull so that his front feet are close together. That opens the killing spot, which, at most, is only as big as a half-dollar. It is obviously very difficult, even under the best circumstances, to go in over the horns, looking down a three-foot sword, and hit that tiny spot.

Manolo yelled again, “No!” But still Paco would not hear him. He profiled, incited the bull with the cape, and plunged in over the horns. The sword went in a quarter of the way, then flipped out. A banderillero retrieved it and handed it to Paco, who was sweating and ashen. He walked back to the barrier to rinse his mouth out. He looked up at his father, who could only spread his hands in a gesture of resignation.

Five times Paco went in over the horns, with no opportunity to make the kill with grace and nobility. The bull would do nothing but stand chopping sideways with his horns. In the end Paco simply gathered himself up and, disregarding the danger, went at the bull in such a way that the sword could not miss. It was a very dangerous kill, but it was effective.

Paco came back to the barrier drenched in sweat. Antonio tried to console him. “You did well with that basket of bones. The best surgeon in Mexico could not have gotten a scalpel in him.”

But that was not the way Paco had wanted it to be. Every novillero wants to be awarded an ear on his alternativa, just as every rookie in the major leagues wants to hit a home run his first time at the plate. The crowd had been sympathetic to his situation, but they were not about to demean the sport by awarding him a trophy for his less than exciting effort. His had been a bad bull, but it is, after all, the job of a matador to make a good bull out of a bad one. And Paco had not done that.

Manolo, in a very nice gesture, dedicated his first bull to Paco. In an amazing feat of technical skill, he ran his sword in and out of the bull three times before he finally killed him. He did it to show his contempt for the quality of the bulls. Before he made the final thrust he gave the president of the bullring a mock salute with his sword, as if to say, “Do you expect a bullfighter of my stature to fight such bulls? You should not have let the fight go on.” It was also his way of telling the crowd, “This young man, who is today becoming a full matador, deserves a better chance with better bulls. I, Manolo Martínez, the number one bullfighter in all the world, can tell you so.”

Then Antonio fought his first bull, received the ear, and was roundly applauded by the crowd. Manolo did a technician’s job on his last bull and retired, yawning, to the barrier. Antonio was awarded another ear on a bad bull that he corrected, and then it was Paco’s last chance.

When the bull came into the arena Paco met him sliding on his knees to do the pass of death. Bull 37 turned out to be the best of the day, but even with a good animal Paco could not achieve the style of Manolo Martínez or Antonio Lomelín. In the end he killed the bull with adequate grace, and the crowd waved handkerchiefs to ask the president of the bullring to give him an ear. One of his banderilleros cut off the ear and Paco paraded around the ring with it while the ladies in the crowd threw roses and purses and the men threw wineskins. Paco gathered the roses up in his left arm, still holding the ear in his right hand. His banderilleros threw the purses back to the crowd and Paco picked up the wineskins and used the wine to wash off his face. He did not drink because he, like all bullfighters, drinks very little, if at all.

In the end he stood facing the president of the bullring, still carrying the roses, and held the bull’s ear aloft in a supplicating gesture. The president did not award him the ear. The crowd wanted him to have it, but the president as much as said to him, “Now you are a matador, and you must earn an ear the same as any other matador.”

That night Paco went to the hotel where Manolo and Antonio had stayed. They were checking out to go to their next bullfight. He embraced them both formally and thanked them. He looked very young in his slacks and sports shirt, and they looked very old in theirs. “I have realized this night,” he told them, “that now I must be in competition with Antonio Lomelín and Manolo Martínez. I must please the crowd the same. I will no longer be treated as a boy, as a novice. It will be difficult, I think.”

A little later Antonio sat in the restaurant. As he waited to be driven to the airport he was asked why he had chosen to become a matador, a question for which there are probably as many answers as there are bullfighters. Paco, confronted earlier with that question, had said, “For the honor of my family.” But Antonio’s answer cut to the heart of the matter. He said simply, “Because it is part of my spirit.”

Asked how Paco had done, he laughed. “Well, he made a lot of mistakes. But what else is to be expected?” Then he became very serious. “The young man took his alternativa. That is nothing. The real alternativa is when you lie on the surgeon’s table with the bad cornada, with the blood draining out of you, thinking, ‘This is the last bull I will ever fight. And he killed me.’ The young man has never had a true cornada. Let him lie on that table and make his prayer, ‘God, please let me have one more bull to fight before I die.’ Then he will be a matador.”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads