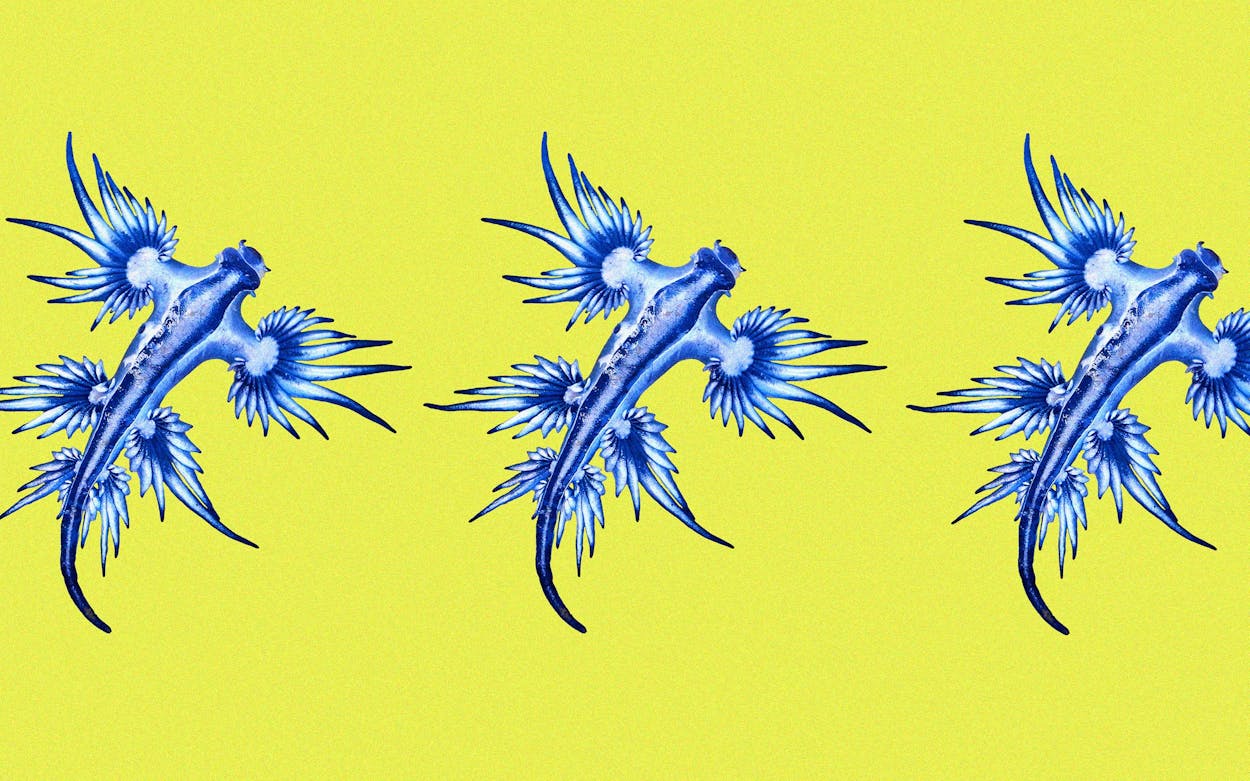

The list of creatures one ought not touch in Texas is quite long, and among the most outlandish entries is Glaucus atlanticus. The small sea creature, which grows to about an inch long and looks like a cross between the Pokémon Gyarados and the blue liquid used in a sanitary pad commercial, is in fact a member of the nudibranch order. Nudibranches are soft-bodied, hermaphroditic gastropods commonly known as sea slugs. The bright blue Glaucus, which gets called everything from blue dragon to sea swallow, lives on the surface of the ocean, moved around by wind and currents, embodying a go-with-the-flow ethos we’d all do well to incorporate more into our own lives. For this reason, they have a tendency to wash up along Texas shores around this time of year, but no matter how much you might want to sequester these bad boys in a Poké Ball, you don’t gotta catch ’em all. In fact, it’s best you stay away, as these living tchotchkes can pack a punch even more potent than that of the better-known Portuguese man-of-war. A single sting could send you right to the hospital.

The blue dragon’s toughness comes from the fact that its primary food source is the Portuguese man-of-war. “That’s what makes them so dangerous,” says Jace Tunnell, the reserve director at the University of Texas’s Marine Science Institute, in Port Aransas. Taking big ol’ bites for such a li’l guy, the Glaucus uses mucus to neutralize the man-of-war’s stinging cells, then transports those same cells through its digestive tract and stores them in its extremities, to be released into anyone dumb enough to try and give it a squeeze. As a result, the blue dragon’s venom is singularly strong. “It’s concentrated, so it’s even worse than man-o’-war sting,” says Tunnell.

Stinging cell freecycling is not the only way Glaucus atlanticus has evolved to be badass. The bright blue color for which it’s earned so many nicknames is actually on its underside. The creature’s ocean-facing back is a gray hue, making it inconspicuous to its underwater prey while blending in with the blue ocean surface. Basically, these ballers live their lives floating on their backs, like this, just casually waiting to munch on one of the sea’s most venomous creations. Sensory-deprivation queens!

The blue glaucus isn’t specific to the Gulf of Mexico—the adaptable critter is also found through the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. It tends to wash up along our shores, though, especially during springtime. “Here in Texas, spring is known for being the windy period,” says Tunnell. “So in March and April, when the conditions get just right and you have big waves and strong southeastern winds, that’s how they get pushed up on our shores.” They’re usually a small part of a greater displacement, accompanying washed-up man-of-wars, blue button jellyfish, pink meanies, and other things you won’t want to touch.

Nevertheless, Tunnell says, it’s hard to actually see a blue glaucus, because they are so small. “And once they get up on the sands, if it’s sunny, they dry up real quick, and then you wouldn’t even recognize them,” he explains. Should a beachcomber stumble upon a washed-up mass of stinging blobs, look for the blue glaucus closest to the waterline. But don’t touch, no matter how much you might want to tickle its ultramarine tummy. Should you get stung, Tunnell says vinegar and hot water are the best remedy for the pain, but that’s for mild reactions. “In very rare cases, there have been people who have died from them,” he warns. “If you get stung in the right spot, and you’re not someone who can handle a sting, and you have a bad allergic reaction, something bad is going to happen.”

Barely bigger than a quarter, hardly ever seen, with a license to kill and a skin tone that resembles the visuals from a particularly wild salvia trip, the blue dragon is an icon of the sea. Indeed, whenever it makes an appearance, it dominates the news cycle. Last spring, when a few were spotted on Mustang Island and North Padre, the dragon was covered not just by local outlets, but by CNN and Newsweek. That’s cultural cachet, my friends—the kind of passive influence that gets you an invite to the Met Gala.

- More About:

- Critters