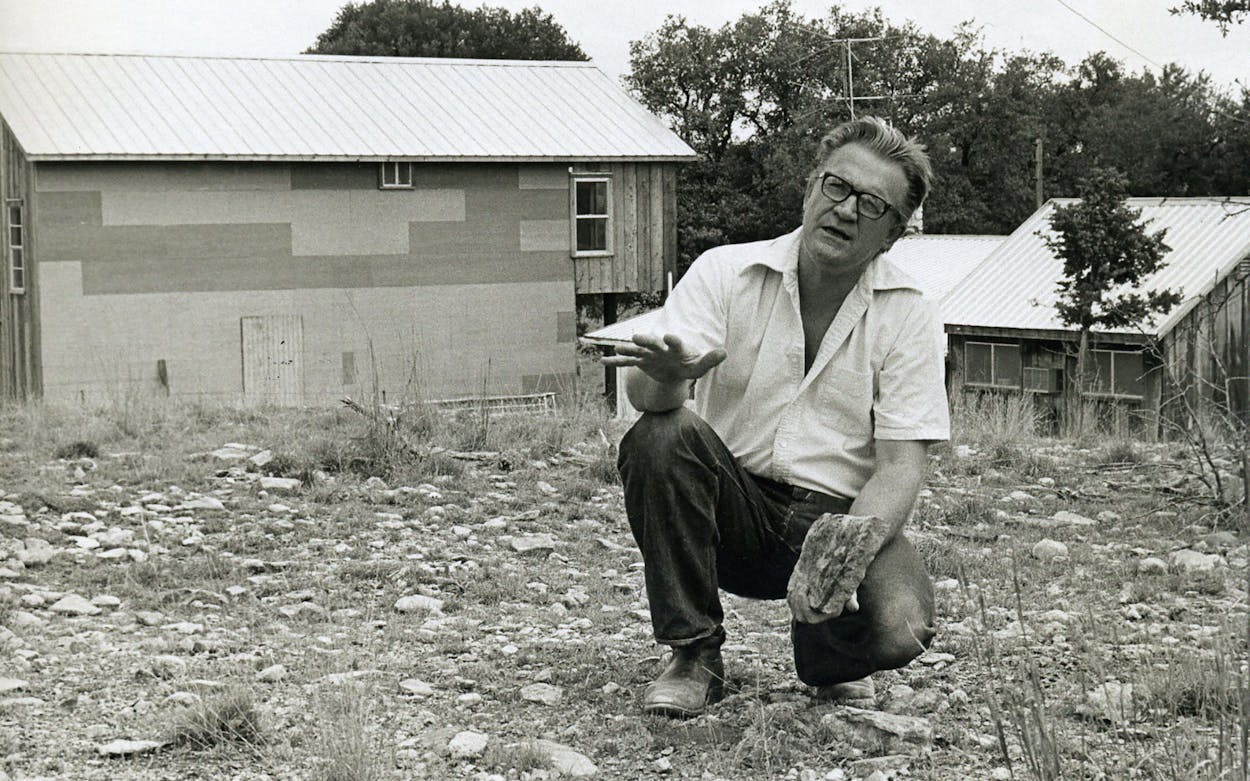

The writer John Graves was of a different era. He was born in Fort Worth in 1920, he attended Rice University as an undergraduate and Columbia University for a master’s in English, and he was injured by a grenade on Saipan, losing the use of one eye, while fighting with the Marines in World War II. By the time he was first published in Texas Monthly, in 1974, he was 53 years old and famous for his 1960 debut, Goodbye to a River, which had been a finalist for a National Book Award.

Founding editor William Broyles—and most of the magazine’s staff—was at the time Graves’s junior by close to thirty years. But if such a venerated writer could be coaxed into working for Texas Monthly, which had been founded just a year earlier, well, that would be a coup for the young publication.

When Broyles penned a farewell to the old writer in 2013, on the occasion of Graves’s death, he recounted a visit to Graves’s ranch, located outside of Glen Rose, which Graves had dubbed Hard Scrabble, to inquire about just such an arrangement. “We walked the land with the dogs, we worked a little on a rock wall, then we sat on the screen porch and I asked John about writing a column for Texas Monthly,” Broyles wrote. “ ‘What about?’ he asked me. ‘This,’ I said, ‘just keep writing about this.’ ”

Graves demurred, basically telling Broyles that he was too old for such work. “I knew that all of us at Texas Monthly, young kids really, needed a literary godfather, a real writer whose presence could anchor and inspire us,” Broyles recalled in the piece.

Graves ended up writing the magazine’s Country Notes column through the end of the seventies and later compiled those stories for a collection, From a Limestone Ledge: Some Essays and Other Ruminations About Country Life in Texas, which was, like Goodbye to a River, nominated for a National Book Award.

“The Loser,” from the August 1978 issue, is a perfect example of such rumination, as well as a perfect example of the work of a “real writer.” Graves recounts a winter drive from Hard Scrabble to a small spread outside of Fort Worth, where there is to be an auction of the remnants of an agrarian’s stab at making a life in the country.

Graves writes: “I was looking at a hatless thin-clad man who sat on the edge of the pickup’s bed beside the auctioneer. He was in his forties, pale and slight and balding and with the pinched waxy look of sickness on him, maybe even of cancer, and as I watched his dark worrier’s eyes swivel anxiously from bidder to bidder and saw the down-tug of his lips when something sold far too low, I knew very well who he was. He was the erstwhile lord of this expanse of wet sand and red mud, the buyer and mender and operator of a good bit too much machinery for 45 arable acres, the painstaking nurturer and coddler of those fat penned cows.” Spoiler alert: this man was, so exquisitely depicted by Graves, the inspiration for the piece’s headline.

Beyond the Country Notes columns, Graves would continue to write for Texas Monthly throughout the years, publishing his final story, “Great Guns,” about the various firearms he’d amassed throughout his life, in October 2006, when he was 86 years old.

John Graves was, just as Broyles had wished, a literary godfather to the staff of Texas Monthly. He did anchor us and he did inspire us, as he does still.

- More About:

- Writer

- Farmers

- John Graves

- Bill Broyles

- Glen Rose