All these years, you figured the Dallas Cowboys had turned mediocrity into an art form for the usual reasons. You know, team owner Jerry Jones, a string of clueless head coaches, self-styled talent evaluator Jerry Jones, and a roster that has way too many underachieving players every single season. Did we mention Jerry Jones?

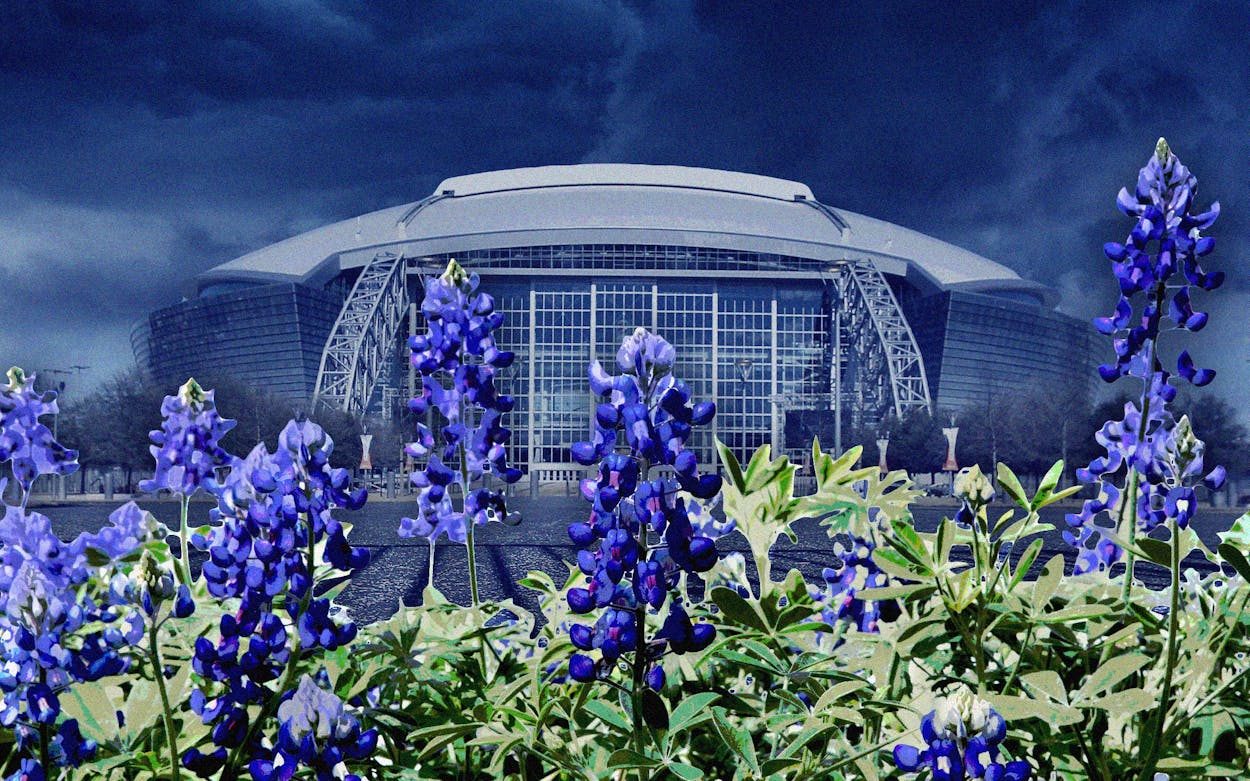

But what if there’s another possibility, and what if that possibility is so over-the-top it might actually make sense? And what if there’s a simple fix? How about the Curse of Granny’s Bluebonnet Patch? And what if it’s reversible? If Jerry would only convert a small square from one of his parking lots into a neat little bluebonnet garden, Cowboys fans could start planning for Super Bowl LVIII in Las Vegas next year.

We jest. Sort of.

Hasn’t Jerry tried everything else? Amid all the firing of coaches and churning of rosters, we’re about to have a twenty-seventh consecutive Super Bowl Sunday without America’s Team taking part. This year’s matchup will feature the Kansas City Chiefs and the Philadelphia Eagles. The Cowboys’ last appearance in the big game was January 28, 1996, during Bill Clinton’s first term.

I telephoned Marcy Smith after she wrote Texas Monthly detailing a possible explanation for why the Cowboys have been unable to reclaim their mantle of greatness since moving into the $1.3 billion AT&T Stadium in 2009. Smith’s theory? It’s a hex from her late grandmother, whose garden was paved over to build the Cowboys’ new home.

AT&T Stadium has marble floors and artwork and one of the world’s largest video screens. In its time, it has become the mine-is-bigger-than-yours goal of every other NFL owner. What the stadium has not had is a championship team. In fourteen seasons at Jerry World, the Cowboys have played just five home playoff games, winning three. They haven’t gotten close to another NFC Championship Game, much less a ninth Super Bowl.

“It’s kind of a joke,” Smith tells me.

Not really.

“I’m still angry.”

Smith and her husband, Edward, live on forty lovely acres in Colorado these days. But Smith grew up on five acres in Arlington, where AT&T Stadium and one of its parking lots now stand. “It was really peaceful,” she says. “We had friends. We played there and in the neighborhoods around it. We’d swing on vines in the creek bed. It was so much fun.”

Amid those five acres were Grandmother Myrtle Smith’s prized gardens, lush with a variety of Texas flowers, including, notably, bluebonnets. Smith still remembers the day the bulldozers took them out. Her grandmother had died years earlier, but Smith’s mother, Evelyn Smith Wray, still lived on the land. To this day, Smith believes the way her mother was tossed from the property has angered the gods of such things.

She has written Jones to voice her concerns, and to plead with him to plant a commemorative bluebonnet garden and possibly coax some positive vibes from the land that has produced mostly disappointment for Cowboys fans. “Every time they get close to the playoffs, it’s in the back of my mind, the way they treated my mom,” Smith says. “I know it doesn’t matter to them.

“I want to tell him, ‘This is what’s going to happen, Jerry: You need to talk to my [late] grandmother. You need a little plot of bluebonnets out there if you really want this to happen.’ In my mind, I can hear Granny agreeing they will never come back and neither will the Cowboys. It’s kind of a joke, but it’s also therapeutic for me.”

Smith mentions the ice storm that blanketed Dallas in the days leading up to Super Bowl XLV, in 2011. That was karma in action. “See what I’m talking about?” she says. “You think they’re done with you, Jerry. They’re not.”

If a little patch of bluebonnets—and some remembrance of Myrtle Smith—might get the Cowboys out of their 27-year rut, why not give it a try? So far, Jones has been unwilling to give Marcy Smith an audience.

Her grandparents, W. B. and Myrtle Smith, had a house on one side of the five acres. Her parents built a place on the other. Myrtle would tell stories of how the family home was built from the lumber of a Presbyterian church. “To hear my grandmother tell it, she pulled out all the nails herself,” Smith says. “My grandmother would play the martyr card all day long.”

That’s where Myrtle tended her bluebonnet patch. After Smith’s grandparents—and her dad—died, her mother lived alone on the property. Then, in 2006, someone from the city of Arlington knocked on Evelyn Wray’s door and told her the city was taking the land by eminent domain.

“She was offered $330,000 for four acres and two houses,” Smith says. (Myrtle had sold one acre to her second husband.) Wray stood her ground, eventually hiring an attorney who, according to Smith, wound up negotiating a sale price of $2.9 million for the land. But the payday couldn’t stop Wray’s heart from breaking. “My mom wasn’t an emotional person,” Smith says, “but she called one morning, and she’s crying and telling me, ‘Marcy, they’re bulldozing the trees.’ That was two weeks before she had to be out.

“Look, the neighborhood wasn’t the same,” Smith says. “Some of the apartments were sketchy. Some of the homes around the land were run-down. My mom’s house had been broken into a couple of times. It was time for her to go. But it was the way they did it.”

Smith says she’ll never forget the day she drove her mom away from the land for the final time. “As we were getting in our cars, she looked into the field that was no longer hers,” Smith wrote in her email to Texas Monthly. “She laughed for the first time in the past several months and said, ‘Myrtle is pissed.’ Her precious blue bonnets will soon be flattened with concrete, and they won’t be coming back. The caravan of cars slowly drove down the driveway onto Randol Mill Road, all of us taking the last glimpse of the rock house with yellow garage doors, finding it hard to believe it would soon be gone.”

And with it, perhaps, the football prowess that once belonged to America’s Team.

- More About:

- Sports

- NFL

- Jerry Jones

- Arlington