This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

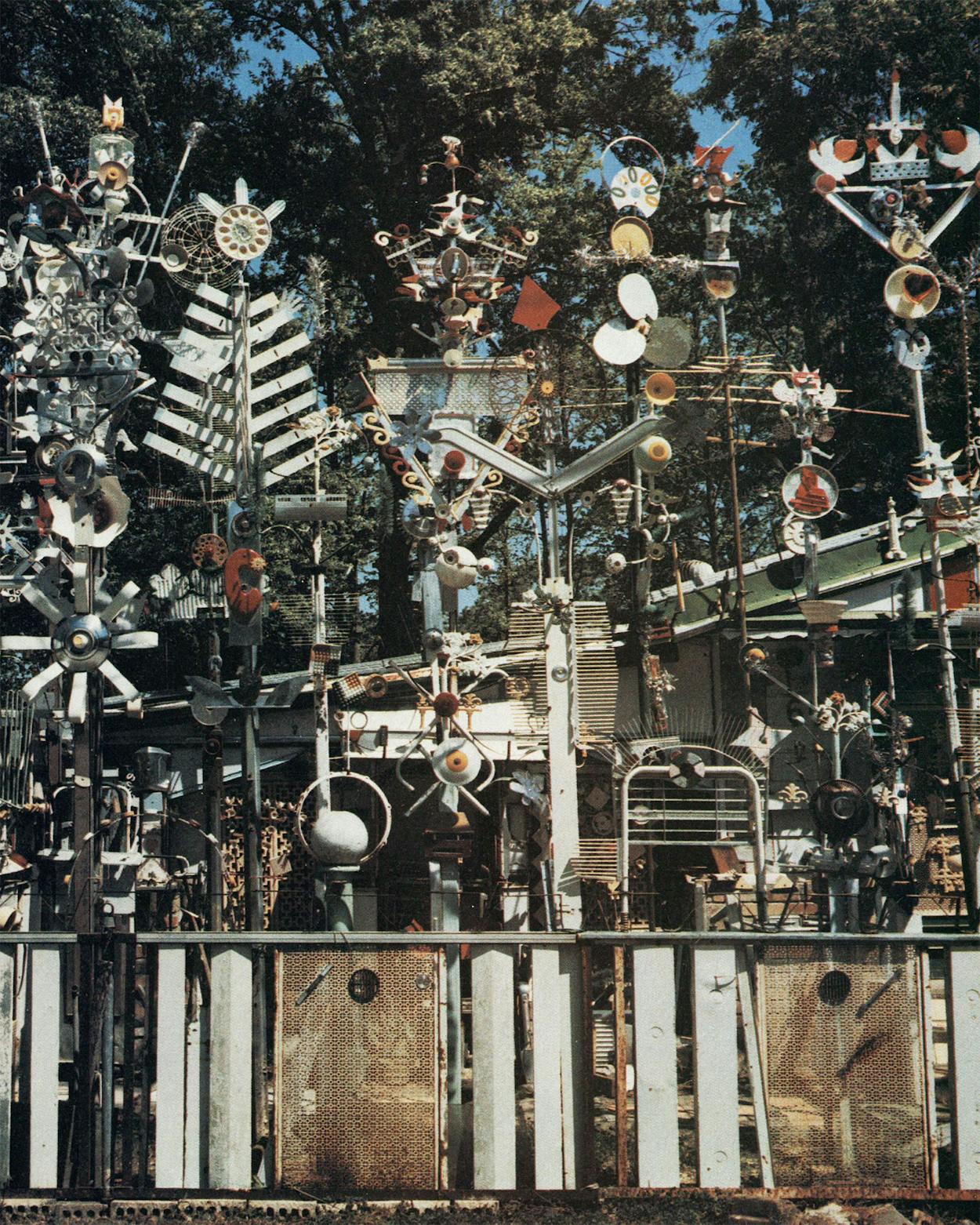

On Ledet Road, in a poor, shambling part of Beaumont, there is a jerry-built house, hunkered and asymmetrical, like a clubhouse that boys might build for themselves in the woods. In the side yard of this shanty is a forest of strange stalagmite sculptures. The tallest are about twelve feet high and are made of metal and adorned with whirligigs, pie plates, chrome auto parts, spoons, forks, coffeepots, cutout tin, refrigerator cooling coils, Venetian blind slats, and baby doll parts. It is a jolting assemblage. Objects that had nothing in common in their former lives now have a united purpose and an unexpected elegance and symmetry. Poised for ascension, they impart an odd sensation: looking at them, you want to stand on your tiptoes.

The man who made them is Felix Harris, known to most people as Fox. This old black man is what students of the genre call a folk artist, a person who starts to make art late in life, often at the urging of God, and whose gift seems to have fallen full-blown from the sky. A folk artist works in isolation from other artists and not for recognition. He has total confidence in his work but is not particularly impressed by it or by himself. At first he appears naive, but he isn’t; he knows exactly what he is doing. The term fits Fox like a glove.

He was born in 1905 in East Texas. He “came up,” to use the vernacular of that region, in the small sawmill town of Trinity. He has been a logroller, a tongue hooker, and a rail pusher, all lumber and railroad occupations, which from a good distance in time sound very rustic and romantic but were simply grueling jobs. Now, at 79, he lives in Beaumont, a widower, estranged from his one son, in the three-room house he built himself. He spends his days, at least the warm ones, pounding and hammering tin into shapes with templates he has designed and then erecting his sculptures. When the weather is cold he stays indoors until he judges that his gas bill is at the limit of what his Social Security check will allow. Then he goes outside and builds a fire in the hulk of an old space heater to warm himself.

Fox’s living room, low-ceilinged and about ten by fifteen, is obsessively decorated. He has tacked metal strips around the walls in a zigzag pattern, metal strips that used to be tracks for adjustable bookshelves. There are religious artifacts—hands clasped in prayer, portraits of Jesus—and a profusion of plastic flowers. One bouquet is stuck in an upside-down set of bongo drums. His living room is also a warehouse for future sculptures, a good many components of which are stacked on an old, out-of-tune upright piano. The piano ensemble is a still life of other people’s discards.

When asked how long he has been making his yard pieces, Fox is vague. Instead he talks about how people, mainly kids, are prone to tear them down. But his neighbor, a square-shaped, loquacious Cajun named Franklin Carmouche, says Fox started some 25 years ago, about the time he retired and finished his makeshift little house. As to why he builds them, Fox is more specific: “The Lord say to me, take nothing and make something.”

Fox, like his sculptures, is attenuated. He is about six two, and everything about him—torso, legs, feet, hands, forehead—seems rendered by El Greco. His nappy hair is swept back and spun with silver, and it looks more like a casque than a head of hair. A powerful norther had blown through Beaumont the day I met him. He was wearing a red and black knit cap, a gray polyester sport coat, gold shirt, dark pants with long johns peeking out the cuffs, socks, and cracked white patent leather loafers, the right one in such decay that it was rigged to his foot with a couple of shoelaces. We sat by the gas heater in his living room. Fox’s memory is failing him, and like many old people, he takes facts and events and rearranges them to suit himself, the way a child stacks and restacks blocks. He talks at times as if Noah, the Kaiser, Abraham Lincoln, and George Washington were contemporaries. His biblical stories ramble, and parts are unintelligible, but all his parables contain a theme that is startlingly clear and a sentence or two that strikes like lightning. His Bible lore is in the oral tradition. He can’t read or write, a bane he has worked over the years into a hairball of frustration, although sometimes he is philosophical about it: “Reading is good—but understanding beats it all.”

Fox cradles his forehead in his long hand to try to bring things back. His mother’s name was Rose Ann Taylor; his father’s, Hance Harris. “He was half-Injun.” His grandmother, Rose Ann’s mother, lived with them. “My grandmother, I was the onliest one she talk to. She told me about the times she was coming up. She been sold three times.” Her name escaped him for a moment, then leaped into his memory. “Jane, Jane Taylor.” He counts off a litany of brothers and sisters—“a brother Clee, Wesley (he double-jointed and could pull up a small tree), sister Nanny, another one Texana, Alfred, Hance, Bubba (he couldn’t talk), Beatrice, John Henry (he the oldest of the bunch)”—but you suspect a sibling or two might be missing from the list.

He got the name “Fox” as a child for outrunning a man on a blaze-faced horse. Fox and his brother Hance apparently took to needling the man. (Fox is wanting for teeth, so many of the details of this and other stories were a mumble by the time they rolled out of his mouth.) “Folks tell us, quit monkeying with the man. We watch, and he roll a cigarette and lit it, then he whirl his horse on me and I took out. I beat him to the house. He come up. ‘Hance, where that boy?’ My daddy say, ‘Who that?’ ‘That Felix.’ Daddy call me around, and that man sat on his horse and look me up and down and say to Daddy, ‘That boy outrun my horse. I call him Fox.’ ”

Fox could dance as well as run. “Thank the Lord I got these foots,” he says. He claims to have been such a sensational hoofer and piano player that people came to try to lure him to Hollywood, that other folks were so jealous of his talents they wanted to kill him—Fox is haunted by would-be assassins out of his past—and that “women drop their cooking to come watch me.” The first two claims, although they may well be true, sound a little like an old man’s embellishments. The last, based on a performance I saw, sounds altogether plausible. Felix is too stove-up to dance, but he hammered out a couple of pieces on his out-of-tune piano. They were fast, maniacal, bluesy pieces, accompanied by a furiously stomping foot and intermittent wailing. It was a fearsome display of energy and rough talent, and it was not hard to extrapolate from it the picture of a hard-drinking man carousing in honky-tonks across East Texas.

But Fox abandoned whiskey and carousing, or, more accurately, God took away his thirst for those things. He got in a scuffle one night outside a bar—at what point in his life this occurred is unclear. “I come home, laid in my bed, and the Lord told me, ‘Quit drinking.’ ” He tells this story with drama and precision; no doubt he’s told it hundreds of times. “When I woke up, God, he take the taste out of my mouth.” That vision, or dream, which must have appeared in the midst of a mighty hangover, is closely connected in his mind with another one in which God put Fox’s burden down (God tossed away a piece of brown paper He had been holding in His left hand) so that Fox could start to pursue a pure and less painful life (God picked up a piece of white paper in His right hand). During the vision, God gave Fox instructions to make things. God told him, “I’ll make a way out of no way.”

Umbrella in hand, I went walking in Fox’s crowded sculpture garden, only to find that my earthly possession was snagging up on the intricate rigs that towered all around me. The lofty pieces are surrounded by a fence that is also decorated with art née junk. If getting old is simply becoming a child again, Fox has all cylinders working. The sculptures are nonsensical and whimsical—the products of a childlike mind—but the pieces are also stately. Fox says he started bolting various objects onto tall metal poles and rods to keep people from stealing them, but that practicality has been replaced, whether Fox intended it or not, by a more spiritual purpose. Those forks, spoons, arms, and pie plates are reaching for heaven.

Fox vacillates between painful remembrances of the past—“I been as low as a grease spot on the floor,” he told me—and profound contentment with the present. Church helps to keep him on an even keel. Every Sunday he goes to Borden Chapel Baptist Church, an occasion for which he dresses in one of the several Abe Lincoln-esque suits he owns. Fox is not interested in selling his sculptures, nor is he even much concerned with what happens to them after he dies. Mr. Carmouche, who is Fox’s alter ego and a good bit more practical about worldly matters, bridles at his friend’s saintly stance. He thinks Fox should sell his work to the highest bidder (assuming there was one), rather than giving up the ghost with no cash in hand for his earthly works, and he’s likewise convinced that people are simply waiting for Fox to die in order to steal away with the things he has labored on for so many years. Listening to the two of them argue, I knew I was a thoroughgoing citizen of Carmouche’s world, but I wanted, however vainly, to be like Fox, and in that respect Fox fulfills his peculiar mission in his little backwater of Texas. He has risen to his occasion. He has made something out of nothing.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Sculpture

- Beaumont