This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Rain don’t fall for the flowers if it’s falling

Rain just falls”

Holed up in his hacienda, Robert James Waller struggles to find himself. The vehicle at this moment is a song wailed by Jimmie Dale Gilmore on the CD player here in this new office-darkroom-studio at the foot of the Glass Mountains. Closing his eyes, cocking his head, and swiveling his ergonomically correct desk chair even closer to the music, Waller looks more like an angst-ridden teenager than the 55-year-old author of The Bridges of Madison County and the savior of American romance.

“You see?” Waller asks, indicating the aptly entitled song, “Rain Just Falls,” on the CD player. “That’s me.”

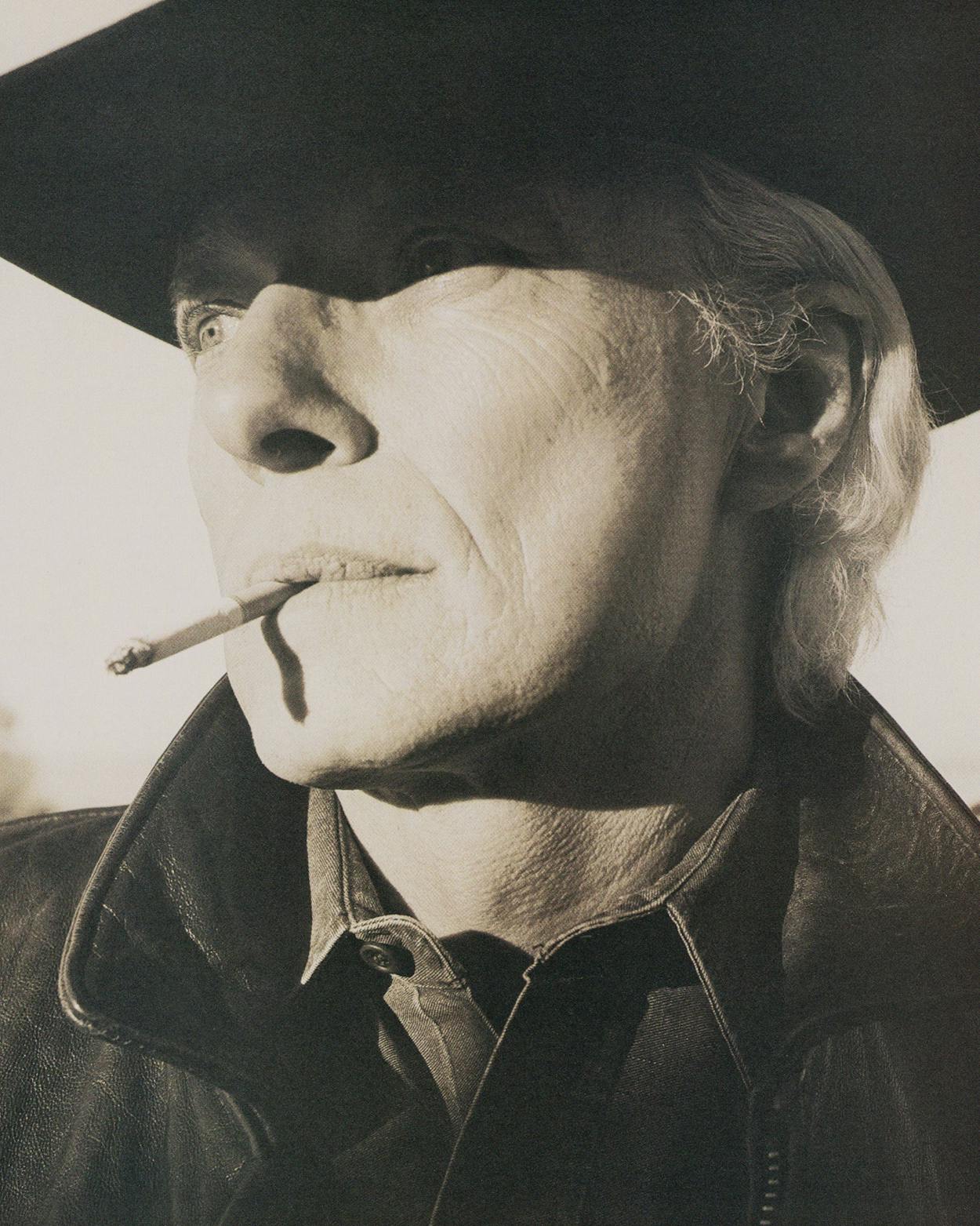

Outside, the West Texas air is as sweet as kisses, the sky over Alpine an impeccable blue, and workmen are putting the finishing touches on the new patio that will precede the new swimming pool. The Bridges of Madison County has been holding steady on the best-seller list for more than two years, and the movie version, starring Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep, hasn’t even opened yet. Loyal dogs laze in the sun. Waller’s wife, Georgia, looks at least 10 years younger than her 52 years. But Waller, immune to pleasure, collapses his tall-drink-of-water frame into an existential shrug. The man famous for creating soft-core, sentimental adult fantasies toughens up: The jutting cheekbones, the tight but broad mouth, the wide-set but narrow eyes, the plunging widow’s peak—all turn as harsh and unforgiving as the landscape just beyond his sun-washed patio. Life for Waller must be harder than it looks. “Ultimately there is no meaning,” he says, pausing portentously. “I couldn’t say it better than Jack Carmine,” he continues, volunteering to sum himself up in the words of one of his own creations, the loner-loser who is at the center of his latest best-seller, Border Music. “We come, we do, we go.”

No meaning? We come, we do, we go? Rain just falls? Isn’t this the same guy who has made a fortune exhorting readers to give up everything to find love, adventure, one last fling? Nine million readers worldwide bought into The Bridges of Madison County, in which a bored Iowa farm wife gets it on with a National Geographic photographer for four days that equal a lifetime. Two million people gave their hearts to Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend, in which a motorcycle-riding economics professor runs away to India to find perfect love with the wife of a colleague. Already, all over the country, Waller fans are pounding on bookstore counters to get ahold of Border Music, in which a Texas drifter loves up and then (stop here if you’re reading the book) loses a topless dancer to his own demons. Waller novels have more trembling, torment, and towering passion than the Lifetime channel, Geraldo, and an Iron John confab combined. So doesn’t Waller have a little more to offer than “we come, we do, we go”?

The truth is, it’s not easy carrying around the secret yearnings of an entire nation. (Ads for Border Music describe it as “an unforgettable journey of love and desire that will dare you to reach beyond the borders of your own life.”) Waller survives—and thrives—by cultivating an elusiveness that is both literal and metaphorical. In other words, wherever Robert Waller happens to be, he wants to be somewhere else. “It’s the essential tension in me,” he says of his contradictions. “The road versus the settled life.” Writing best-sellers, he dreams of resuming his old music career (the former bar musician has released a CD, The Ballads of Madison County) or heading back to India to take pictures (Waller now has a second book of photographs in the works). Happily married to the same woman for more than thirty years, he turned a story of infidelity into a gold mine. Declaring himself a nonserious sort of soul, he is nevertheless profoundly indignant at the trouncings he regularly receives from the East Coast literary establishment. (New York‘s Walter Kirn wrote of Border Music, “Freed by guaranteed best-sellerdom to write as poorly yet self-importantly as a person can, Waller conquers whole new realms of wrongheaded lyricism and off-key poetry”; Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times merely deemed the book “spectacularly awful.”) Finally, having fashioned for himself a life as rich, full, and unfettered as humanly possible, Waller feels compelled to declare its essential meaninglessness. You may be inclined to wonder just who is joshing whom. Or who is joshing himself.

Either way, Robert Waller has come to this remote corner of the state to define himself anew, to escape the fallout of media stardom (the tourists who caused traffic jams on his cul-de-sac in Cedar Falls, Iowa; the company that wanted to market Bridges suspenders and other fashions), and to pursue once again a life that is honest and true. The need started roughly two years ago, after what he calls “the Bridges tidal wave.” At that time, this lifelong Iowan felt the needle of his internal compass directing him south and west. He wanted a place that would satisfy his need for both fantasy and authenticity. For passion and for peace. For fame and obscurity. In short, a place where he could have it all.

Like the man said, rain just falls. We come, we do, we go. And sometimes, it’s to Texas.

“We’re gonna look at the pumps and the wells,” Waller says, folding himself into a dusty 1968 Ford Bronco. For lots of reasons, this particular daily ritual takes on a theatrical aspect when Waller is in charge. Partly it’s because Waller, tall and skinny in creased jeans, dark aviator glasses, cowboy boots, and a spotless ink-black Stetson, looks more like a Bavarian king on holiday than a West Texas rancher. Partly it’s because most patrones—certainly those as rich as Waller—could probably find a ranch hand to keep an eye on the property’s water system. It’s also true that Waller has shared this late afternoon ritual with more than one journalist. In some strange, postmodern way, he has given an emotional component to a chore once required for physical survival: Checking stock-tank levels, climbing up tank ladders, and tightening pump-jack packings is clearly soothing to Waller, proof that he is evolving into the cowboy he has long longed to be. “I tend to use ‘cowboy’ in the metaphorical sense,” he says of his affection for his latest incarnation. “Getting up every day, being responsible for your own life. Plus, there’s something visually satisfying about it—old dogs, old trucks, and shit-kicking music. I just like the way it all fits together. ”

This new identity sure looks real: There’s brush, there are mountains, there are cattle (he leases his land to a local rancher)—there are even wild animals. “We ran a lion up a tree a few weeks ago,” he says proudly. Most authentic of all is Waller’s passion for Texas. He watches the weather (“They’re called northers here, blue northers”), drives his jeep as if it were a cutting horse—his dogs nipping at its wheels—and, like everyone, is awed by the imperviousness of the land and the sky. Even so, the sight of Robert James Waller making himself at home here may make some Texans a little queasy.

“To my way of thinkin’, dancin’ lady, somewhere out ahead, west of Junction, there’s kind of a space-time curtain rifflin’ in the wind,” Border Music‘s Texas Jack Carmine tells his recently acquired lover, a former topless dancer named Linda Lobo, on their way back home from Minnesota. “And out beyond that curtain blowin’ around on the southern run of the high plains lies another land entirely: West Texas. You’ll see what I mean before long. Different place altogether, and if you feel it, you’ll live it and start believin’ you’re from a foreign country compared to everythin’ else of an American nature.” Texans who have never before ventured into Waller country—those unaccustomed to the overblown, torrentially emotional landscape his characters inhabit in The Bridges of Madison County and Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend—are going to have to brace themselves for the treatment given their home state. Suffice it to say that Cormac McCarthy, Elmer Kelton, and Larry McMurtry can rest easy. On paper at least, Waller is more interested in making Texas over in his image than in succumbing to any image Texas has ever been known for. Being more concerned with universal themes like love and loss, he has no use for the Texas myth or the Texas character. The place is pretty much like anywhere else, except that people drop their G’s and hang out at a few genuine landmarks like the Holland Hotel and the Crystal Bar. The weather, which even the most half-hearted Texan ignores at his peril, is barely mentioned. Characters experience the land not as conquerors but as tourists: Rattlesnakes aren’t a problem when Jack Carmine and Linda Lobo buy an air mattress and take it up into the mountains so they can make love under the stars. “[I]f one crawls across you,” Jack advises, “just lie still and pretend it’s me doin’ somethin’ wholly different and exotic to you; that’ll set you free, turn you into a buffalo gal.” Waller’s West is sanitized and suburbanized, and his hero, Jack Carmine, has less in common with cowboy culture than with the culture of narcissism.

So maybe it was no wonder that Waller was the subject of some derision when the talk started that he was moving here. He was dismissed as a pale Midwestern wannabe in the gossip sections of several Texas publications; even the friendly Dallas Morning News could not resist taking him down a peg. The lead for a story on Waller’s arrival in Alpine had him walking into the office of Parsons Real Estate and saying he wanted to buy a big ranch—maybe a thousand acres. You could see the punch line coming, of course. “Wellsir,” owner Flop Parsons told him. “Around here, a thousand acres is little.”

People wanted to believe that Texas was too tough for a tinhorn like Robert Waller. Nearly every profile of his West Texas life notes how remote the region is, that you can drive for miles without seeing a soul, that you can get only one station on the radio. But what would be striking to anyone returning to West Texas after an absence of several years is how much less remote it is: UPS and Federal Express serve the area; a cellular phone office is open for business on Holland Street. The Cinnabar Restaurant features flaky croissants and movie stars; at the ALCO discount store you can buy futons, treadmills, and posters of Green Day. The work of the late minimalist artist Donald Judd attracts international visitors to Marfa; Marathon’s Gage Hotel has accommodations that rival any place in Santa Fe.

Everywhere there seem to be young, hip, urban types who are looking for property: Forget Austin, they will tell you; Wimberley is overrun too. Alpine is the new nirvana. Alpine seems to agree: IF YOU DON’T OWN A MOUNTAIN YOU SHOULD, urges one local realtor’s billboard. Technology has made once-remote places like this feasible for people like Waller, who maintain a love-hate relationship with mass culture. Thanks to cable, computers, faxes, and airline connections, members of this techno-landed gentry can have it both ways; they can have an urban life in the country, they can sample the isolation without really having to submit to it. And the Old West, more and more, is just so much decoration. At Haley’s Trading Post, which was recently featured in a Chevrolet Suburban ad, rattlesnake rattles go for $7 apiece.

Perhaps that is why, finally, Alpine took Waller in without much grousing: The old days are gone, and anyway, he’s not a phony, he’s a fan. “Texas has such a sense of its heritage and loves its heritage and tries to preserve it,” he says. “I always felt I wanted to be part of a place that feels that way. Iowa was not like that.” Waller donates to local civic groups and assists friends in need. He helped “real cowboy” Sam Cavness find work as a location scout for a Lucky Strike ad, for instance. He and Georgia join locals for country and western dance nights. And so, the new-old man reinvents the Old-New West. His ever-present Stetson comes from Johnson’s Feed and Western Wear, but his jacket comes from the J. Peterman catalog. He switches to nonalcoholic beer when he drives, he shoots javelinas when he has to but feels nauseated afterward, he is teaching the cook to substitute soybean products for meat on occasion. He cries. “I weep easily and I’m not ashamed of it,” Waller says. Brewster County, known as the place where the misfits fit, has just made room for another one.

And possibly even more: “It’s New York after all—a syringe,” Waller’s daughter, Rachael, announces later in the day. She is standing beside U.S. Highway 90, staring at a bright white needle plunged into the dirt. Returning to Waller’s home with take-out Chinese (yes, from Alpine), she spied her father at work and stopped the car. Rachael’s husband, Vincent Young, has now been pressed into service, holding a photographer’s light while Waller poses for a sunset photo to be used in this magazine. Here too is a glimpse of the melting pot that will soon be Alpine: Vincent, of Puerto Rican descent, has close-cropped hair, both of his ears are pierced, and he is dressed appropriately for a young man from the Bronx—in a black T-shirt and black jeans. He met Rachael after she dropped out of high school before her senior year and left Iowa for New York to become, first, a tour manager for rock bands and, later, a nanny. They married here, to the strains of a mariachi band, and Waller bought them a neighboring ranchette. Now Rachael spends her days studying equestrian dressage. Two more immigrants complete the tableau: Behind the Hasselblad camera is James Evans, an ebullient photographer from Philadelphia who is assisted by his wife, Gene Krane, who is originally from southern Louisiana. All five of these people on the side of the road now call the Marathon-Alpine mini-megalopolis home.

“Idn’ this beautiful country?” Waller pronounces as the sun, oblivious, turns the sky carnelian. “It’s the last frontier.”

“Hello, Iowa. Sorry ’bout the Stetson,” Robert Waller says, tuning his guitar onstage at the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines and not sounding sorry at all. The curtain behind him shimmers with artificial stars. He is wearing black boots and his black hat with his tuxedo and cuts a gleaming, definitive figure. The occasion is Music for Lovers, a concert in honor of Valentine’s Day, “a holiday that makes us maybe a little bit better as Americans,” according to the emcee. Waller is the opening act for Paige O’Hara, the voice of Belle in Beauty and the Beast, and her husband, Michael Piontek, who played Raoul in The Phantom of the Opera. It’s a typical pop concert crowd, indistinguishable from a similar audience in California, New York, or Texas—average age is about sixty. The sameness can be disorienting to someone looking for the distinctly Iowan, especially when one gentleman in the crowd begins talking knowledgeably of Ross Perot and North Dallas real estate values. (Evidence of the shrinking nation is everywhere: The coffee shop at Waller’s hotel featured crab-and-cilantro quesadillas.)

Waller, too, makes no effort to play the hometown boy, even with his mother and a handful of old friends in the crowd. If anything, with his agent, editor, and the president of Warner Books, his publisher, looking on, he’s more reminiscent of a horizontal corporation. Waller reads a sweetly evocative essay, “Excavating Rachael’s Room,” from a collection published before Bridges but rereleased by Warner in a new compilation last year. “The Madison County Waltz,” a contagiously schmaltzy ballad he performs with admirable technical skill, is essentially a spin-off of Bridges for nonreaders. (“He was a cowboy, the last one it seems / a rider of sundowns, and old faded dreams . . .”) “Bandit” is a song that premiered in Border Music. Tuning up for another country song, Waller straightens his Stetson and shares some patter with the white-haired crowd about Brewster County (“1.4 people for six thousand square miles”) and his life there. “I called a friend from Muleshoe, Texas, the other night,” he says, his Texas accent broadening. “I said, ‘Gilbert, I’m gonna sing one of your songs tonight.’ Ah, Gilbert,” he continues, dropping his eyes to stare lovingly at his guitar, “we drink Lone Star and so on . . .” The message to the audience is plain: I am not of you anymore. My home is elsewhere.

It’s easy to ascribe such a transformation to cynicism or commercial convenience. In Waller’s case, though, slipping into new identities is more like a congenital compulsion. Start dissecting his personality and you find a man who has willingly subscribed to the male social dictates of the past three or four decades—all of them. He’s a he-man (“I’m pretty much of a lone wolf”); he’s a sensitive man (“I did my own laundry before it was chic”). He’s a roamer; he’s a family man. He plays the outlaw while he climbs the corporate ladder. In today’s self-help parlance you could say Robert Waller hasn’t a clue who he is—but you could also assert that he just wants to be everyone at once. “I’m comfortable with the world of ambiguity,” he says. He’s the quintessential baby boomer, embodying all the ambition and all the angst of the age of Oprah.

There is the proverbial struggle with home. “I spent my life trying to please my father,” he told People magazine in 1993, “but I never knew him.” It has become a part of Waller’s official biography that his father, a chicken wholesaler, dissuaded him from a career in the arts but encouraged him in basketball, at which Waller obligingly excelled, attending the University of Iowa on a basketball scholarship. (By then he’d married his teenage sweetheart, Georgia Ann Wiedemeier, who not surprisingly described their relationship to People as “magical.”) Then, also to please his father, Waller pursued a career in business management by acquiring a doctorate from Indiana University, eventually winding up as the dean of the college of business at the University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls. “My father thought being a professor was better than being president of the United States,” Waller says.

It was an impressive climb by any standard. Progressing from scholarship student to college dean, Waller developed an appreciation for what he calls “the value of the small increment.” “I knew I wasn’t real smart,” he says, “and I’ve never been a believer in big kills. You just get up every day and work hard and work smart, but you’re always making an investment in yourself. Eventually, it pays off.”

And you never stop. “I’m an obsessive,” Waller likes to say, and indeed, there is a desperation to his earlier years, in which he strove to make it both conventionally (to please authority) and unconventionally (to please himself). While pursuing his business career he continued a sideline as a professional musician—guitar, banjo, and flute—usually performing in Holiday Inn lounges, but once on Robert Kennedy’s campaign train. (From Current Biography: “Waller has said Kennedy’s sense of commitment made a deep impression on him . . . ”) In 1983 he also dabbled as a freelance writer for the Des Moines Register, composing surprisingly restrained (for him) and effective essays on everything from his twenty-fifth wedding anniversary to the river otters of Sweet’s Marsh, Iowa. Waller also at one point worked on an economic plan for the state and traveled the world as a corporate consultant. Affecting blue jeans, long hair, and cowboy boots, he had it both ways: He was a rebel and a conformist.

Then in 1985, at the age of 46, he had the obligatory epiphanic hospitalization, an episode of nervous exhaustion mistaken for a coronary. “The poet got caught in a fight with the dean and the poet won,” Waller says, proudly quoting his doctor’s diagnosis. The doctor gave Waller his cigarettes back and told him to find a beach for a month or so. Like any smart yuppie, he financed his hiatus with his American Express card. When he returned to work, however, he found his tolerance for higher education diminishing. “I couldn’t empathize with the students,” he says. Political correctness, the baby boomers’ babies’ revenge, was in full bloom: “Give somebody a bad grade, they’d call you a racist.” Waller, reduced to the proverbial besieged white male, took an unpaid leave in 1991 and with his wife started living on his savings. “We canceled all our magazine and newspaper subscriptions. We threw our credit cards in drawers and went to ground,” he says. Poverty didn’t scare him. In the early days, when they had been short of money, Waller had sung in talent contests, losing out to the likes of teenage baton twirlers. “When you’re hungry, there’s no shame,” he says. And if you aren’t gifted, it pays to be very, very determined.

Waller had taken up photography in 1986 and had found some jobs doing commercial projects. In the summer of 1990 he suddenly had an impulse to shoot, well, the bridges of Madison County, Iowa. In the process, he was gripped by what is an almost universal fantasy of male photographers: that around the next bend waits a beautiful, bored, and very hot babe. Waller went home and in fourteen days committed this notion to paper in the form of a novel. Following a friend’s recommendation, he sent the work to superagent Aaron Priest. What followed was, in Priest’s words, “one of the best marketing jobs I’ve seen in years.” Mainly through Warner’s personal nudges to independent booksellers, which in turn inspired enormous word of mouth, the book took off. Fifteen months after Bridges was published in April 1992, three million copies had been sold.

In retrospect, the novel is perfect for boomer consumption. It’s short (for those short attention spans), and it looks good. The cover, an understated illustration of a bridge in muted colors with an equally understated type treatment, makes the novel look literary, which appeals to the affectations of the upwardly mobile. (Bridges’ first fans were in fact residents of posh suburbs, like Darien, Connecticut.) It was touted by mega-boomers from Microsoft’s Bill Gates to Oprah Winfrey, who called it “a gift to the country.” But mainly it succeeded because Waller’s fantasy matched those of the vast majority of Americans: He validated their belief that for every person passionate love, or at least very good sex, is possible—and, perhaps more important, you can find it after forty. (From Bridges: “[T]o him, intelligence and passion born of living, the ability to move and be moved by subtleties of the mind and spirit, were what really counted. That’s why he found most young women unattractive, regardless of their exterior beauty.”) It didn’t matter that the story didn’t resonate with a sense of place, because there weren’t many authentic places left anymore. It didn’t matter that the characterizations were thin: People just projected their own longings onto the page and kept reading. And if the critics carped—which they did, vociferously—Robert Waller pretended not to care. “I can compete with these people in any league they want to move in,” he says sharply.

Finally, Robert Waller had it all. As a best-selling author, he could be an outsider and an insider at the same time. He was the voice of his generation. His yearnings were their yearnings, his strivings were their strivings, his confusion was their confusion. He was no longer alone.

Then came the Japanese man, arriving at his doorstep in Cedar Falls with an interpreter, asking to see the house. (“You’d look out the window and a flashbulb would go off,” Georgia remembers.) The shot glasses and sweatshirts featuring Roseman Bridge, the one he had immortalized in his novel. The copies of Bridges awaiting autographs, hundreds of them, some arriving without return postage, totally obscuring first the dining room table and then the dining room. Four lawyers, an accountant, an investment adviser, too many new best friends. Reporters asking whether he deserved his success. (“It’s not like winning the lottery,” he says in response to that frequently made assumption. “You too could have this if you worked thirty years, fourteen hours a day, and hoped for some luck.”) So much for connectedness; the lone wolf in Robert Waller started pining for a place in West Texas he’d seen on one of his road trips.

“Mr. Waller Is Unable to Grant Autographs Tonight,” the sign on the civic center’s green-room door says. Waller confides wearily, “It starts and then it never stops.” Even so, after a little post-concert coaxing, Waller steps into the crowded space with the concert’s conductor, a small, sharp-featured man named Joseph Giunta. Panic rimming his usually cool blue eyes, Waller leans back against a wall and stares. The crowd, consisting of no small number of little girls carrying Beauty and the Beast coloring books, stares back. “What do I do here?” Waller asks Giunta.

“Well, you can stay and chat or go back in,” the conductor replies.

“I’d rather go back in,” Waller says, heading for his dressing room.

But this place is crowded too, with well-wishers who call him Bob or Bobby, and he soon decides to take his chances with the strangers back in the green room. In succession, Waller is set upon by a woman claiming to be a character in his second best-seller, Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend, (“I was the only Ob-Gyn in Cedar Falls”) and then by a pair of middle-aged twin sisters awed by Border Music. “Texas Jack Carmine—he’s my dark side, uh-huh,” Waller says uncomfortably. For a man living in the shadow of his characters, he’s suddenly caught without a script. Relief comes only when, several minutes later, someone asks how he likes living in Texas. Waller beams, and his accent kicks in. “Way-ell,” he says. “We’re ten ars outta Dallas, four ars outta El Paso. Ar ranch is the only break in the fence for mahls. It’s wahld country, the last frontier. Ah lahk it.”

“This is Nashville music, not real country music,” Waller grouses, lighting up a cigarette and leaning over a rail that overlooks a small, dimly lit dance floor. In spite of his complaints, Waller is expansive this evening at a club in Manhattan called Denim and Diamonds, “a shot of country with a splash of rock and roll.” Someone in Warner’s publicity department thought this Houston-based chain would be the perfect place to welcome Waller to New York. Now, amid mirror-studded saddles, videos of bull riders, cowhide banquettes, and display cases of gimme caps and bolo ties, publishing executives don complimentary bandannas and try to learn to line dance in an effort to honor the man who single-handedly brought tens of millions to the company. “His tide has lifted all boats at our place,” says Warner Books president Laurence Kirshbaum.

“They’re not gonna learn shit doin’ this,” Waller says as a cowboy-hatted employee demonstrates the basics on the dance floor. “Put the music on.”

Except for the coat check guy, who’s from Big Lake, Waller is the most authentic Texan here. While everyone else looks a little awkward, skirting the dance floor as if it had cooties, he cases the party in his black Stetson, strobe-wielding party photographer trailing behind. He jaws with his German publisher (“Remember me from Munich?” the man asks, handing him the new German translation of Slow Waltz), chats up Texas music (“Jimmie Dale Gilmore—not too many people have heard of him, but he’s really somethin’ ”), and just like in a real honky-tonk, asks women to dance by making meaningful eye contact and cocking his thumb and chin toward the dance floor. “Get sexy and slide” are his instructions to a New Jersey woman tackling the two-step for the first time. For all his talk, Waller’s own dancing is pretty stiff. “I never learned to dance till I went to Texas,” he confesses. “I’m not a natural dancer.”

That the usual New York book party suspects (Fran Lebowitz, Diane Sawyer, and the like) are missing in action is not surprising. It’s hard to imagine anyone with literary pretensions wanting to be seen anywhere near any ersatz kicker bar, much less one that’s the scene of a party honoring Waller. No writer in recent memory has been so vilified by the critical establishment; Waller’s work has inspired a whole subgenre of mega-mean literary criticism. “I don’t know anyone who has read the book,” The New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane sniffed. “I don’t know anyone who knows anyone who has read the book. . . . The victorious sales of The Bridges of Madison County make it a more depressing index to the state of America than Beavis, Butt-head, and Snoop Doggy Dogg put together.”

Eventually, you start wondering who to root for. Waller isn’t advocating setting fires, frog baseball, or murder in the first degree, after all. As agent Aaron Priest says of Bridges, “This book speaks to people. To take the view that all book readers are idiots is absurd.” For better or for worse, it is Robert Waller who best taps into the lonely hearts of the American public. Internal longing is soppy and, well, simple. It is Waller’s particular and peculiar gift that he articulates the dream of perfect love in the language most people actually dream in. Love Story, you recall, was not known for its complexity either.

Which is not to say that Waller is a major talent or that, as Priest asserts, the critics assail him because they are jealous. He’s not a craftsman. (Profiles and press releases stress how quickly he writes his books. He could afford to slow down.) His characters are, essentially, sketched in, and though they are more recognizable than most critics give him credit for, they aren’t always that likable. Waller is so entranced by his male heroes that you tend to think it’s accidental that he got Jack Carmine’s self-pity just right, as well as the self-importance of Slow Waltz‘s Michael Tillman. And anyone who has spent an extended period of time around photographers will know that Robert Kincaid’s self-absorption rings all too true.

There is also a problem with repetition: Basically, Waller tells the same story over and over again. A loner (“one of the last cowboys”) meets an irrepressible but oppressed woman. They experience something like lust at first sight (“[T]he slow street tango had begun. . . . And the sound of it blurred his criteria and funneled his own alternatives toward unity. Inexorably it did that, until there was nowhere left to go, except toward Francesca Johnson”). They have very good sex (“You’re the best, Robert, no competition, nobody even close”). Then the man is called back to The Road, the woman returns to her old (dull) life, and yet both are fulfilled because they have experienced an all-encompassing, all-sustaining love. It’s the perfect fantasy for an age of diminished expectations. Wish for a little, you just might get it. At any rate, it was enough to propel Border Music to number three on the Times best-seller list two weeks after its release.

For the most part, Waller is pleased with his accomplishment. “Overall, I’m happy with my work. I love Border Music, I really do,” he says. A new novel, Puerto Vallarta Squeeze, is due out in the fall. Even so, he’s still visited by the usual restlessness, the kind that might give his publisher a coronary. “I was telling Georgia the other day, I don’t know how long this writing’s going to go on,” Waller says. “Maybe we’ll do nuclear physics next.”

But not just yet. As the book party winds down, Waller can be found on one side of the bar, regaling a cluster of attractive women. One in particular, a curvy blonde of a certain age in a short black dress, listens raptly. It’s as if fate has brought them together. She’s the Cosmo editor who condensed Bridges when it ran in the magazine. “After I finished,” she says of that project, “I had to close my door and cry. ”

As Waller chats her up, his Texas metamorphosis is complete. He looks like a ranch hand on the town. His hip is cocked, and he holds his longneck and cigarette in one hand. “You wouldn’t believe how big it is . . .” he says, waving his hand across an imaginary Texas horizon. His Stetson’s still high on his head, just in case a little rain might fall.

- More About:

- Books

- Writer

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Alpine