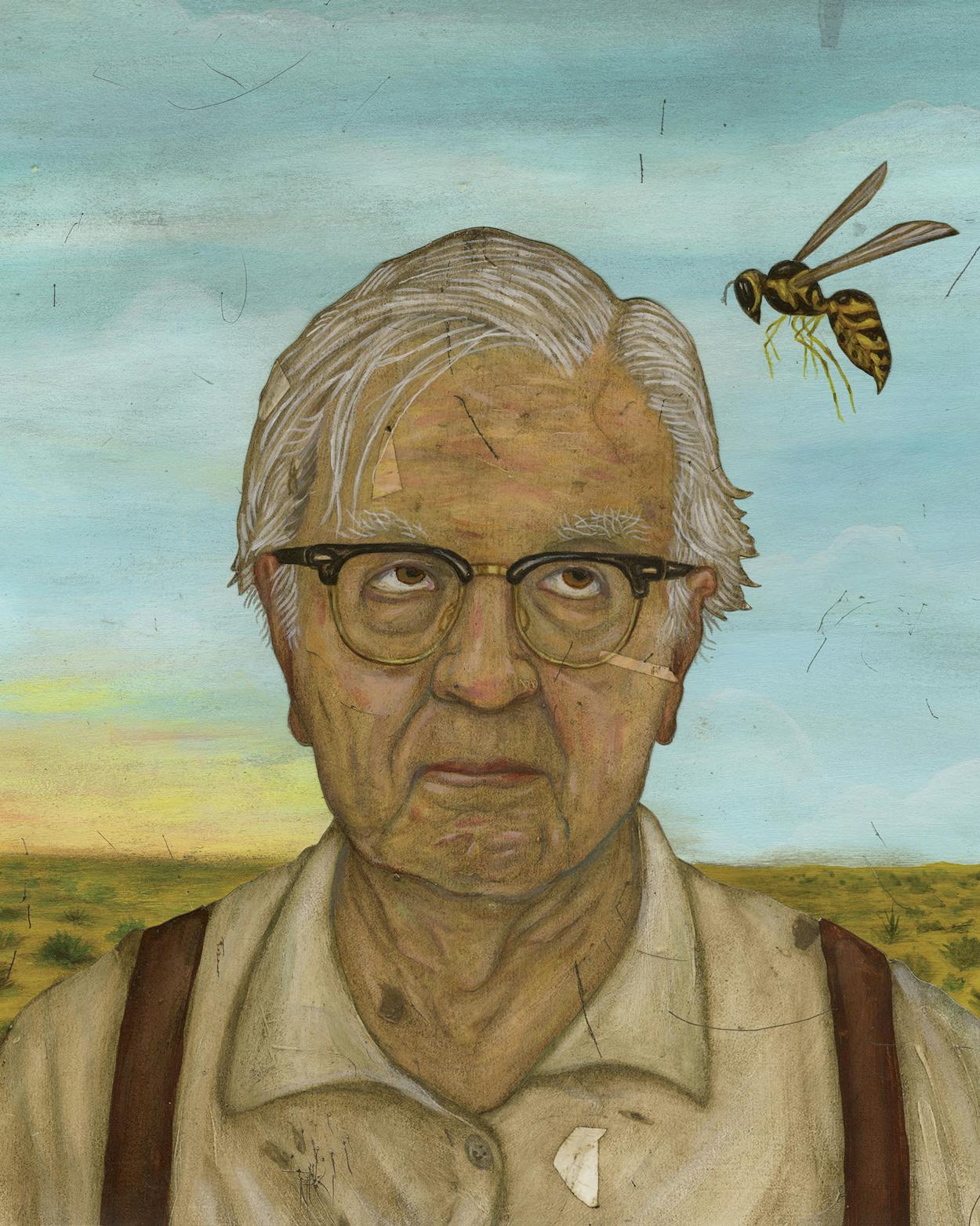

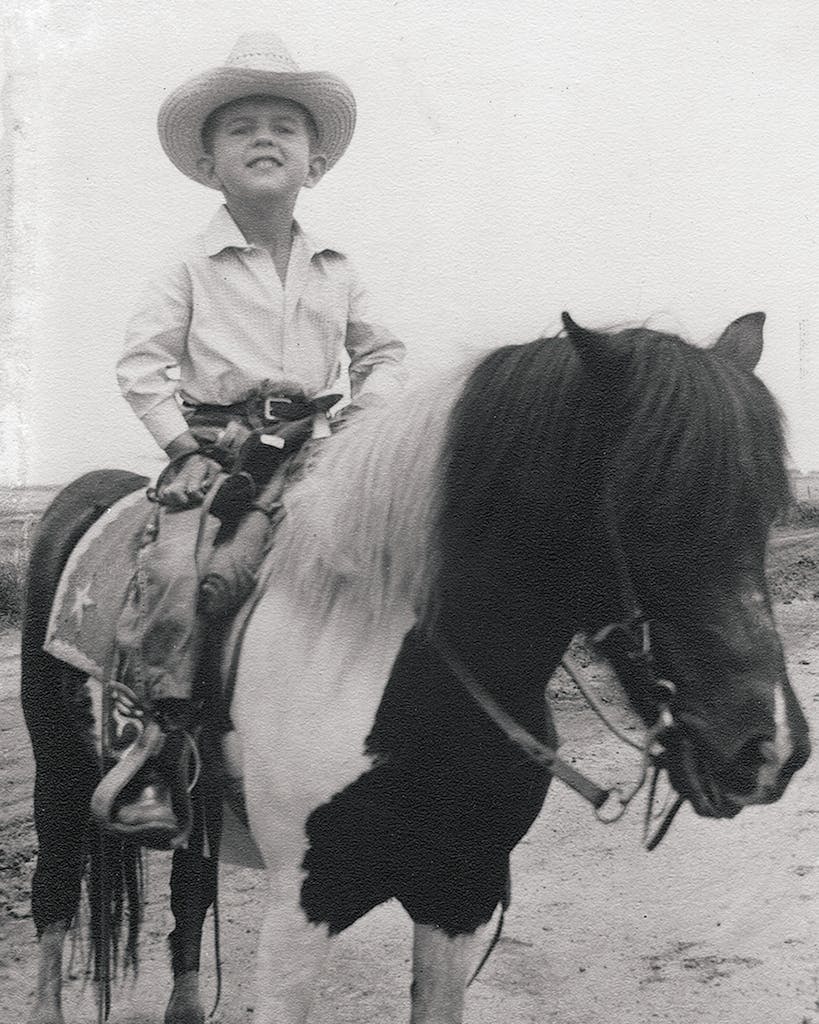

Larry McMurtry boasted impeccable Texas bona fides: his paternal grandparents had arrived in the state in the 1870s and entered the cattle business during its open-range heyday. But despite these bloodlines, McMurtry showed neither aptitude nor affection for the hard work of ranching. When he was three, his father, known as Jeff Mac, gave him his first pony, which, Tracy Daugherty writes in Larry McMurtry: A Life (St. Martin’s Press, September 12), “he promptly rode into a swarm of yellow jackets in a mesquite thicket, getting stung twelve times.” He didn’t fare much better on his inaugural cattle drive the next year. What’s more, he was skinny, his eyesight was poor, and his manner was excessively mild. As Daugherty notes, “It was clear to Jeff Mac and all of McMurtry’s uncles that the boy was not going to be a cowpoke.” Instead, the most famous son of tiny, desolate Archer City grew up to be a self-described “word herder” who wrote, collected, and sold books.

If McMurtry was ill-suited to the world of the hypermasculine Great Plains cowhand, it likely didn’t bother him all that much. As Daugherty explains, McMurtry found most men predictable, even boring. Women, on the other hand, fascinated him from an early age, initially as objects of desire (first stirred by the magazines and paperbacks he encountered at Archer City’s five-and-dime) but far more meaningfully as friends. As McMurtry wrote years later in a letter to the novelist Ken Kesey, “I have a long string of female confidants, stretching back to high school, in each of whom I have invested a great deal emotionally, and from each of whom I have taken some self-discovery.”

But most poignantly, as Daugherty insists, McMurtry was out of step with the geography and topography of far North Texas itself. Whereas many have embraced the majesty of its yawning blue horizon and sea of undulating green grass, McMurtry saw only a dun-colored bleakness, underscored by the region’s economic and cultural impoverishment. Daugherty cites a formative episode from the novelist’s boyhood when McMurtry was traveling with Jeff Mac across the Great Plains on Route 66. “I thought my father was driving us into the sky,” he later wrote. “The image always haunted him,” Daugherty writes, “a vision of escaping emptiness by heading into an even greater blank, as clean as a piece of paper.” Nomadism became McMurtry’s way of papering over the void: contrary to the pithy bumper sticker, he may have been born in Texas, but he got away as fast—and as often—as he could, spending much of his life in Arizona, California, and the Washington, D.C., area.

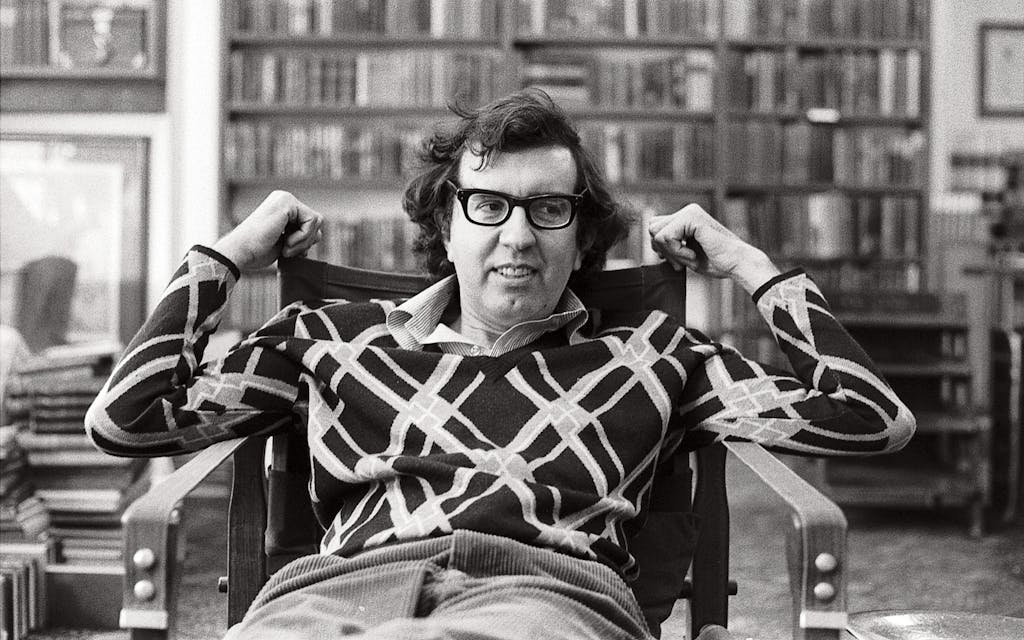

Little of this is news to anyone who followed McMurtry’s career with even moderate attention; his skepticism about his home state is a staple of his interviews and essays. But seeing all of the evidence gathered between the covers of one book, over the course of more than five hundred pages, brings this aspect of McMurtry’s persona into higher relief. It might have been easy, prior to Daugherty’s biography, to regard McMurtry’s carping about Texas as something less than a conviction—not invented, exactly, but exaggerated as a form of personal branding. Perhaps he thought such an offering to the East Coast literary establishment would help him gain access to their world. But such suspicions fade away as one reads these pages, prompting one to wonder: If McMurtry disliked Texas so much, why did he keep returning to it again and again, as both a subject of his work and a place to call home?

The main achievement of Daugherty’s book is to make clear that McMurtry’s deep knowledge of and frequent disdain for the state was a combustible mixture that fueled his writing. This plays out most famously in his best-loved work, Lonesome Dove. McMurtry was hardly immune to the romance of the ranching life; he spent countless hours as a child mesmerized by family stories and dime-store pulp fiction.

But having seen firsthand the difficulties and privations of this existence, he knew that the iconic figure of the cowboy was an avatar not of independence but rather of a wage laborer on horseback. McMurtry once went so far as to declare—hyperbolically, of course—that ranching was “a form of slavery.” And he intended Lonesome Dove as a corrective to those myths. Yet somehow, through an alchemy he never managed to fully explain, he wound up resurrecting those legends for a new generation of readers who were willing to accept a pinch—but no more—of revisionist history with their Tales of the Old West.

McMurtry’s cynicism about Texan manhood offered him one further insight, which is perhaps less celebrated than it should be. Long before academic historians had given the subject much thought, he weighed the costs borne by women on the Texas frontier. As he once explained in an interview: “I think that women had a terrible time in the early West. . . . It was a masculine culture and to some extent crude, to some extent fascistic, certainly not welcoming to women.” He recalled from his childhood how his father “found it difficult to forgive women the ease of modern arrangements—something as simple as tap water,” given how hard his own mother had worked. Although many of his most enduring characters are testosterone-sweating men, Terms of Endearment’s Aurora Greenway and Leaving Cheyenne’s Molly Taylor are just as vividly drawn as, say, Hud from Horseman, Pass By or Sonny and Duane in The Last Picture Show. McMurtry’s last editor, Robert Weil, gushed that “he and Tolstoy are the two great [male] novelists who can depict women.”

But as Daugherty makes clear, it wasn’t just old, rural Texas that McMurtry regarded with mixed feelings. He was also uneasy about the state’s intense modernization over the course of his lifetime. Yes, he once described Houston as “my Alexandria, my Paris, my Oxford”—a series of analogies surely never made before or since. But he fretted that an increasingly urbanized and suburbanized Texas was becoming more like any other place—and recognized that something important was lost in that transformation.

Which may explain why, even as he fled from the loneliness of small-town Texas, he orbited Archer City like a satellite throughout his life. It was there, in a refurbished mansion, that he lived on and off, without air conditioning, during the last years of his life. (He died in Tucson in 2021.)

Daugherty, a Midland native who has penned biographies of Joan Didion, Joseph Heller, and his fellow Texas writers Donald Barthelme and Billy Lee Brammer, is a steady guide through McMurtry’s world, though perhaps a bit unimaginative. He draws on and quotes so heavily from McMurtry’s work that at times the reader might feel as if they’ve been handed a headset and offered an audio tour narrated by McMurtry himself.

That said, this book, which was not authorized by McMurtry or his estate, is not a hagiography. Daugherty’s McMurtry occasionally comes off as cantankerous and vain, even pretentious. After all, who titles a book “Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen” and then, in an interview with the New York Times, cites it as one of the three best books ever written about Texas?

Taking back the proverbial microphone would have required Daugherty to engage in more of the sort of labor one expects from full-scale biographies. Though he consulted some archival material—McMurtry’s papers, housed at several Texas repositories, as well as those of figures including Kesey and Susan Sontag—this component of his research feels thin. Nor are there all that many fresh interviews. Daugherty’s notes and acknowledgments indicate that he interviewed perhaps a couple of dozen people (several of them associated with this magazine, which has covered McMurtry extensively).

But given the length of McMurtry’s career, the variety of media he worked in, and the many different places he lived, it’s easy to compile an extensive list of the writers, editors, agents, scholars, bibliophiles, booksellers, book critics, actors, directors, and family and friends whose thoughts and memories could have made for a more vivid, insightful, and, one might hope, surprising book.

Among the most pressing questions left unanswered by Daugherty’s biography is how to account for the maddeningly uneven quality of McMurtry’s work. Especially in his later years, McMurtry chipped away at his own legacy by producing multiple clunkers, including sequels and prequels to some of his finest novels, which had the unmistakable effect of corrupting the originals, much like the metastasizing Star Wars franchise. Daugherty notes this unfortunate trend but leaves the heavy lifting to unsparing book reviewers. If, as McMurtry confessed, he often wrote for money, should this change the way we view his writing? It would have been interesting to hear Daugherty’s take on this uncomfortable question.

McMurtry’s next biographer—it seems inevitable that there will be one, perhaps several—might consider the failed cowpoke’s lifelong fascination with the legendary cattleman Charles Goodnight as a helpful point of entry. A fictionalized version of Goodnight appears in several McMurtry books, and he served as the inspiration for Lonesome Dove’s Woodrow Call.

It would be difficult to summon a figure less like McMurtry than his beau ideal, who is the archetype of Texas masculinity. It was Goodnight who, as a member of a Texas Rangers squad, recaptured Cynthia Ann Parker from the Comanches. He helped blaze an eponymous cattle trail to Colorado in 1866 and remembered years later that the happiest days of his life had been spent herding livestock. He was strikingly handsome, with dark eyes, black hair, and a thick black beard. And by establishing an enormous ranch on the floor of Palo Duro Canyon in 1876, he opened the region for white settlement, earning the sobriquet “Father of the Texas Panhandle.”

Perhaps McMurtry admired Goodnight, in spite of himself, for those attributes that the dreamy word herder could never hope to embody. But maybe something else was at play. While much of McMurtry’s work is an ambivalent requiem for a fading way of life, Goodnight had felt a similar discomfort much earlier, as suggested by a silent film he made in 1916. Old Texas depicts the Panhandle as it had been when Goodnight arrived, in the mid-1870s: empty and beckoning, rich with possibility. But the movie leaves little doubt that this moment has passed. Goodnight drives home the point by staging a last bison hunt, allowing some of his Kiowa neighbors to chase down one of his buffalo, killing and butchering it in a traditional way. The tone is unmistakably elegiac. Long before Larry McMurtry came along, Mr. Texas himself had already turned off the lights and closed down the frontier.

Andrew R. Graybill is a professor of history and the director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Terms of Estrangement.” Subscribe today.

Remembering McMurtry

More than three dozen writers contemplate the legacy of Texas’s most beloved author.

Not long after Larry McMurtry died, a symposium was held in his honor in Archer City’s Royal Theater, the venue made famous by The Last Picture Show. A dozen writers spoke about the man widely regarded as Texas’s greatest novelist. This gathering, in October 2021, was the seed of Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry (University of Texas Press, September 5), a collection of 38 essays edited and curated by George Getschow, one of the event’s organizers.

There are some big-name authors here, such as Geoff Dyer, Paulette Jiles, and Diana Ossana, as well as plenty of current and former Texas Monthly writers, including Sarah Bird, William Broyles, Oscar Cásares, Gregory Curtis, Stephen Harrigan, Skip Hollandsworth, John Nova Lomax, W.K. Stratton, Katy Vine, and Lawrence Wright. But perhaps the most moving tribute comes from the Native American novelist Stephen Graham Jones, who at 23 was awed by the sight of McMurtry when he paid a visit to Booked Up, McMurtry’s legendary Archer City bookstore. “I’m still in your bookstore,” Graham writes, 26 years later. “All of us listed in the table of contents, we’re bunched down at the end of that aisle, and we don’t really want to leave. Even after you nod once, push your book dolly back into the shadows, we’re still looking into the space you just filled.” —Andrew R. Graybill

This sidebar originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Remembering McMurtry.” Subscribe today.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that McMurtry died in Archer City. He died in Tucson.

- More About:

- Books

- Writer

- Larry McMurtry

- Archer City