Paul Reubens, who was most famous for portraying the bizarro eighties icon Pee-wee Herman, died on Sunday, a month shy of his seventy-first birthday, after a six-year struggle with cancer. Reubens wasn’t a Texan—he was born in New York and lived most of his life in California—but his greatest work, 1985’s Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, was surprisingly influential in defining the Texan identity for a whole generation of non-Texans.

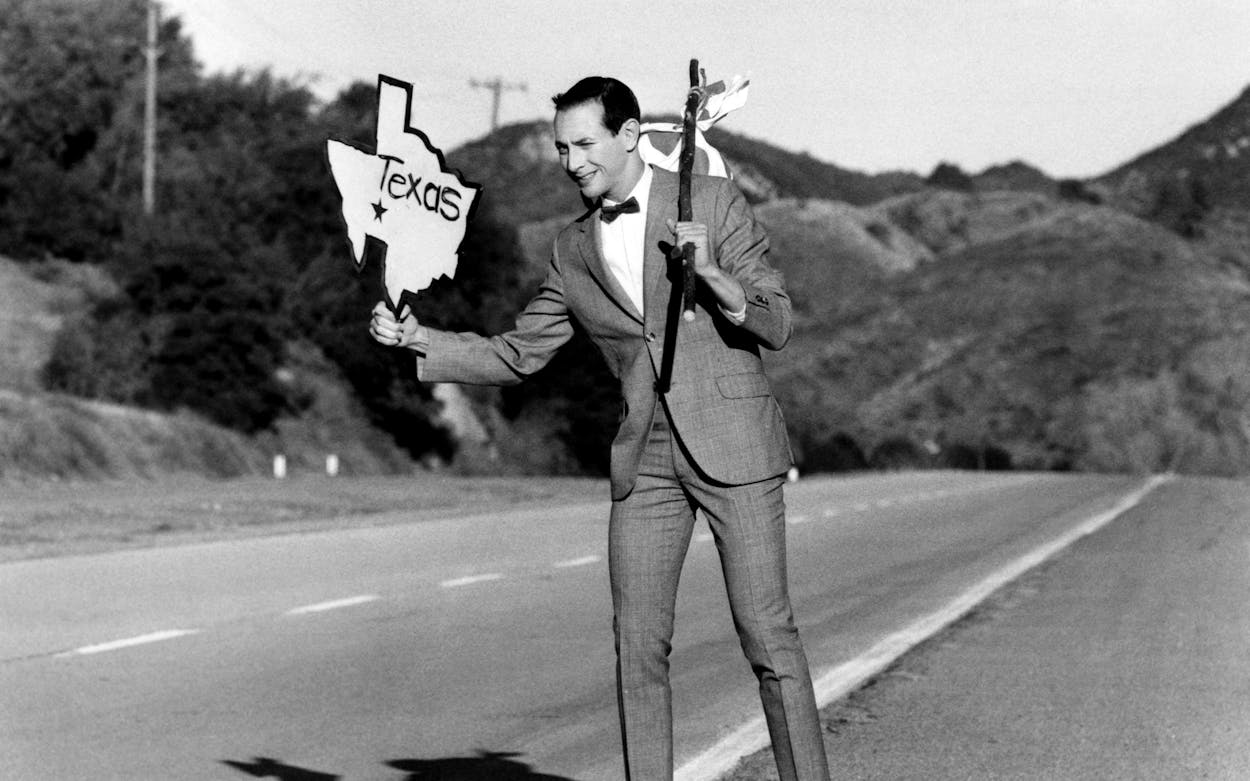

The film (which is also the debut feature of director Tim Burton) centers around the title character’s mission to find his stolen bicycle, which he’s told by a psychic is in the basement of the Alamo. That’s an absurd premise befitting a character steeped in absurdism—Pee-wee lived in a magic house, wore a gray plaid suit with a red bowtie, and appeared on late-night talk shows and in other movies in character. But the depiction of Texas, through Pee-wee’s quest in the hit film, helped define the state in the imaginations of non-Texans.

Pee-wee spends the movie adventuring to San Antonio, where he learns two important things: first, that Texans are incredibly proud of their state, and second, that there is no basement in the Alamo. Growing up in Indiana, I didn’t learn a whole lot about Texas history in school—believe it or not, it’s not a subject that gets taught much elsewhere—and for years, the only thing I really knew about the Alamo was that it didn’t have a basement. I wasn’t alone in associating the words “Alamo” and “basement” because of the movie. Alamo tour guides frequently answer questions about it from smart-aleck tourists, and if you find an adult between the ages of 35 and 50 in, say, Minnesota right now and ask them to name three facts about the Alamo, I’ll bet you twenty dollars that they’ll say the word “basement” before they say Davy Crockett’s name. (Also, the Alamo kind of does have a basement now—there’s one under the gift shop, though it wasn’t built until at least four years after Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. Inspiration can come from anywhere!)

When I moved to Texas at eighteen, it turned out that the stereotype of the state offered by the movie was more or less true. Remembering the Alamo is incredibly important to a number of Texans. (Indeed, disparaging the old mission is so verboten that Texas leaders have been known to shut down challenges to its official mythology.) The call-and-response that follows “The stars at night are big and bright” is indeed so ingrained in the Texas psyche that you probably heard four claps the moment you read those words. Big Adventure’s image of a Texan is broad, sure; Texans wrote Forget the Alamo, after all, and there are surely some Texans somewhere who are unmoved by “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” But it’s also a gentle—even loving—version of the stereotype. The Texans in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure are welcoming and friendly, and they seem to want nothing more than for Pee-wee to share their love of the state.

When I moved here at eighteen, that was my experience too. These days I can clap along with the best of them, and I have my own favorites among the figures at the Alamo (Crockett, Susanna Dickinson, Juan Seguín). I decided to stick around because, as it turned out, that depiction of Texans I got from Pee-wee Herman as a little kid turned out to be pretty accurate.

Reubens didn’t spend a whole lot of time in Texas. After a 1985 screening of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure at the Alamo, he didn’t return until 2011, when he served—in character—as a guest judge on Top Chef: Texas. But he treated the state with a good deal of affection and warmth, at a time when it might have been easy to be snide or dismissive instead. That earns him a place, however bizarre or surreal, in Texas lore, and we’ll remember that as part of his legacy.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Obituaries

- Film

- San Antonio