It can be hard to meet your heroes. In the spring of 1871, the American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson left Boston to take his first and only trip to the far West, where he encountered a sawmill operator named John Muir. The two men seemed to have much in common: Emerson was the leading light of the transcendentalist movement, which emphasized the basic goodness of humanity and nature, and Muir later became a celebrated preservationist and cofounded the Sierra Club. Yet Muir was disappointed by his encounter with the famed author, who was so timid that he declined an invitation to camp in Yosemite Valley, lest he fall ill in the night air.

Muir’s disregard for Emerson, though, pales in comparison with the sentiments of the Texas-born author John E. Williams. The plot of his 1960 novel, Butcher’s Crossing, which turns on an 1870s buffalo hunt that devolves into an orgy of mindless slaughter, was a pointed critique of the sanitized view of the natural world held by men such as Emerson, who, Williams said (with exaggeration), had “never got very far beyond Brookline, Massachusetts.” If Emerson had truly experienced the West, Williams suggested, he and his northeastern admirers, accustomed to the relatively tame fauna and low-slung peaks of New England, would have discovered that nature, however majestic, can also be brutal and unforgiving, devoid of spiritual meaning, and suffused with a terrifying nothingness.

Like much of Williams’s other work, Butcher’s Crossing quickly slipped into obscurity, selling fewer than five thousand copies before falling out of print. With the release in October of a powerful movie adaptation, directed by the documentarian Gabe Polsky and starring a brilliantly cast Nicolas Cage, Butcher’s Crossing seems poised for discovery by an audience familiar with the canon of revisionist westerns. Before authors such as Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy transformed contemporary literature about the frontier era, Williams presented readers with some grim truths about the period—lessons that we would, today, do well to heed.

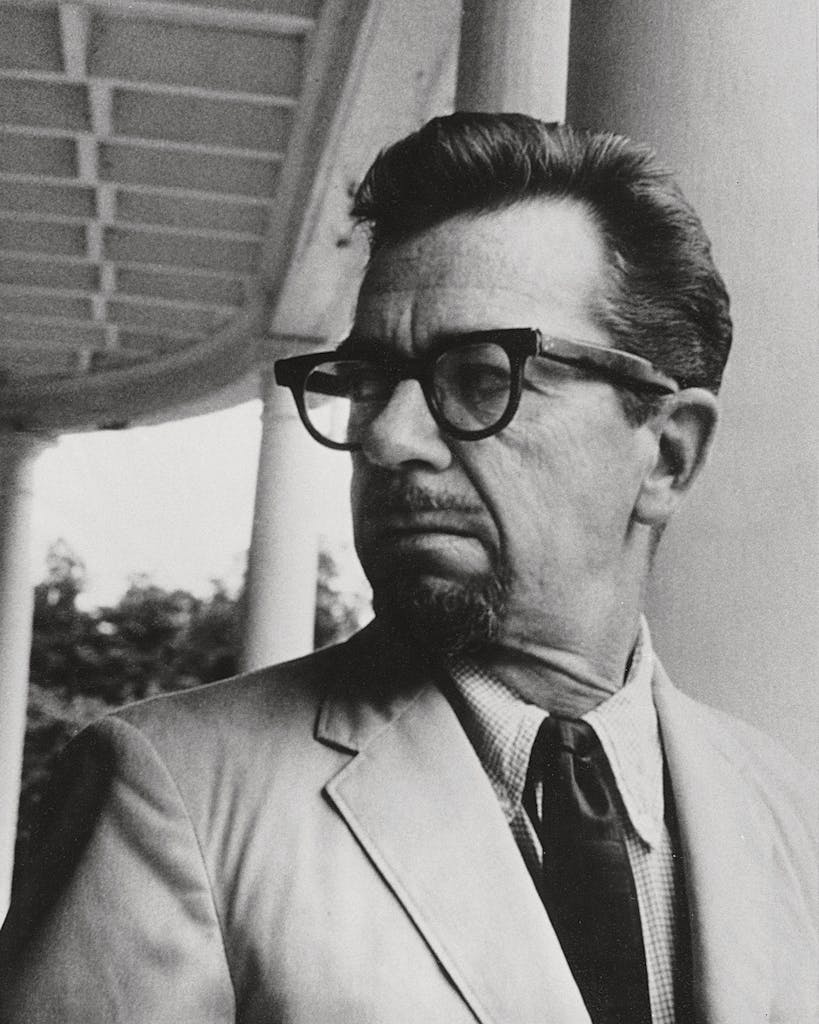

Williams was born in 1922 in Clarksville, sixty miles west of Texarkana, and grew up poor in Wichita Falls, where his stepfather worked as a janitor. John Ed (as the younger man was then known) followed a different trajectory, characterized by sartorial flamboyance and an insatiable appetite for reading. He briefly attended a local junior college but dropped out and took a job at a radio station.

In 1942 he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces as a radioman and was stationed in South Asia, where he flew “the Hump”—the resupply route from India to China that crossed the Himalayas—in a C-47 transport. He claimed he was once shot down, and though his biographer is skeptical on that front, it’s clear that the war affected Williams deeply. As his widow explained, “It never went away. Two and a half years of killing, killing, and killing.”

After the war, Williams published his uneven first novel, Nothing but the Night (1948), about the strained relationship between a father and his dissolute son. On the advice of the book’s publisher, he enrolled at the University of Denver, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees there, followed by a doctorate in English from the University of Missouri, in 1954. The next year he returned to Denver, where he directed the school’s creative-writing program and led a turbulent personal life characterized by multiple marriages and alcoholism. Upon his retirement, in 1985, he and his wife settled in Fayetteville, Arkansas, home to that state’s flagship university, which now holds his archives. Elliott West, a historian friend of mine who taught at the school for decades and was Williams’s neighbor for a time, remembers him as “cantankerous . . . [and] more than a bit jaded,” traits compounded no doubt “by tubes up his nose and an oxygen canister next to him while he sat chain-smoking.” Williams died in Fayetteville in 1994 at age 71.

On one occasion Williams said of his readers, “There are not many of them, but that’s all right. . . . Would a hundred thousand good readers make you a hundred times happier than a thousand good readers? I doubt it.” This equanimity served him well, since even after winning the National Book Award in 1973 for Augustus, an epistolary novel about the life of the first Roman emperor, he was largely ignored, including in his own academic department. Renown came only in 2006, when New York Review Books reissued Williams’s 1965 novel, Stoner, a portrait of the interior life of a beaten but unbowed college professor that was hailed by one critic as “something rarer than a great novel—it is a perfect novel.” (A fine biography of Williams by Charles J. Shields, published by University of Texas Press five years ago, is titled “The Man Who Wrote the Perfect Novel.”) Stoner found legions of new readers in the United States and became an international bestseller in places as far-flung as Italy and Israel.

Butcher’s Crossing was inspired by Williams’s own encounter with the West after he first arrived in Denver, which fueled his sense that “the whole transcendental business” broke down beyond the Missouri River. The naiveté of the movement’s devotees is embodied in the character of William Andrews, who, roused by hearing Emerson lecture and reading some of his works, drops out of Harvard and heads west, arriving in the dusty Kansas town of Butcher’s Crossing. As he explains to a merchant there, “I came out here to see as much of the country as I can. . . . I want to get to know it. It’s something that I have to do.” Will soon falls in with a hunting outfit, led by a man known only as Miller, who for years has been obsessed with returning to a small valley in the Colorado Rockies where he claims to have once spotted a herd of five thousand buffalo. Will agrees to fund the expedition, and they add a cook and a skinner. The group heads out in late August, intending to return in six weeks.

After a rough traverse of the Great Plains—including a desperate search for water that Williams describes unforgettably, with horrors besetting the men and their animals alike—Will finds what he came for when they reach the mountains. In a scene from the movie (which follows the book faithfully but not obsessively), Will (Fred Hechinger) marvels at beams of sunlight streaming through a pine forest and shouts rapturously to the cook: “This is God!” But the mood dims quickly as the killing starts and it becomes clear that Miller (Cage) intends to wipe out the entire herd. In a character sketch found in Williams’s archives, he describes Miller as “Basically anti-human. Fully (yet fanatically) alive only in the hunt.” Cage, sporting a shaved head and a thick beard, summons the controlled mania of his better midcareer performances in movies such as Face/Off and Lord of War.

Williams made clear that he was not sentimental toward the buffalo, which he dismissed in a newspaper interview as “simply a glorified cow.” Yet his description of the carnage will move all but the hardest of hearts. On the first day of the hunt, Miller slays 135 animals and afterward walks among them with a dazed Will: “They threaded their way among the buffalo, some of which had fallen so close together that their bodies touched. One bull had dropped so that its huge head rested upon the side of another buffalo; the head seemed to watch them as they approached, the dark blank shining eyes regarding them disinterestedly, then staring beyond them as they passed.” Schneider, the skinner, then instructs Will in the gory art of dressing a bison carcass, flaying the skin and then tearing it from the body with the help of a rope tied to a saddle horn. Will’s inaugural experience gutting a calf is rendered even more graphically and ends with him in a river, scrubbing furiously and trying—like Lady Macbeth—to get the blood out.

Still greater traumas await Will and his companions, portended by a single flake of snow, “large and soft and slow, like a falling feather.” By the book’s bleak end, everyone has been stripped of whatever dreams of the redemptive—or merely remunerative—West they may have had. One of the men dies in an accident, another is consumed by a terrifying rage, and Will finds himself headed west on horseback, alone, unsure of his destination.

Williams speculated that Butcher’s Crossing passed without much notice “because it was pushed forward as a western, and of course it’s not,” by which he meant that it did not conform to the genre’s mythic tendencies. All the same, a reviewer for the New York Times considered it a western, just not a very good one, writing that the book “contains little excitement and moves as though hauled by a snail through a pond of molasses.” Of late, more perceptive critics have praised it as an “antiwestern,” given its explicit subversion of the stereotypes laid down most famously by Owen Wister in his 1902 novel The Virginian, which features clearly drawn good guys and bad guys and culminates in a showdown. Butcher’s Crossing wasn’t the first “antiwestern”—that honor may go to Oakley Hall’s Warlock, which preceded it by two years. But it staked out thematic ground later explored by more famous books such as Little Big Man, True Grit, Lonesome Dove, Blood Meridian, and The Son.

The term “antiwestern,” though, is a bit of a misnomer, as it suggests little more than binary opposition, when in fact Butcher’s Crossing offers piercing insights into the American West. Perhaps it would make more sense to think of it as an “authentic” western that gets the little details right while landing on a bigger, far more important truth: the West, rather than a site of transcendence, was a region exploited by what Williams termed “capitalism run amok,” a notion at the center of the “New Western History” that emerged in the mid-1980s.

In manuscripts found among his personal papers, Williams wrote that “it is peculiarly American to avoid the past” and that “we fear it because it shows us what we have become.” While Williams’s critique of our discomfort with history courses through each of his three major novels, it is acute in Butcher’s Crossing, given that the American West serves as an especially unforgiving mirror. The tens of millions of bison that were whittled down to a few hundred are merely emblematic of the wider pillaging of the Western landscape; consider all the gold and silver dug from the earth, the scarce water resources diverted for industrial agriculture, and the sod-busting that helped to create the Dust Bowl. Even a valley in Yosemite—which so enchanted Emerson in 1871—had a dam built in it to create a reservoir, despite Muir’s heroic crusade to protect it. And this is to say nothing of the genocide perpetrated against Indigenous peoples by those who sought control of the region.

In a 1973 academic essay considering the challenges that face the historical novelist, Williams quoted the English writer Robert Graves, who observed that, for those fiction writers wishing to bring the past to life, “it is hardly enough to retell accepted history with dramatic embellishments; there should be a ghost clamouring for justice to be done him.” The phantasms Williams conjured in Butcher’s Crossing—above all the despoliation of the natural world—have haunted us since Emerson’s time. As anyone paying attention to the depletion of Texas’s groundwater, the pollution of our gulf and rivers, and the destruction of our native animals’ habitats knows all too well, they haunt us still.

Andrew R. Graybill is a professor of history and director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said Yosemite Valley was dammed to create a reservoir. This article has since been updated, as of October 18, 2023, to note that the dam was built in a valley in Yosemite, not Yosemite Valley itself.

This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Greatest Western You’ve Never Heard Of.” It originally published online on October 16, 2023, and has since been updated. Subscribe today.