This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

You can champion a cause, but you can’t cause a champion. Champions cause themselves. When they set out to win, they do win, whatever their pursuits—and their pursuits are many. There are poker champions, who win a lot of money, and baseball champions, who win a lot of fame and a lot of money. Win a Nobel or an Oscar or an Olympic gold medal (Texans have done all three), and you’re indisputably a champion; eat 4003 jelly beans at one sitting or stand in a pig trough for 39 days (Texans have done neither), and you’re a somewhat questionable champion. Be Gene Autry’s horse and you’re a champion in name only.

But these are famous champs. They are admirable, true, but they’ve had their day in the sun. What about the people who shine in less exalted spheres, champs who are recognized only by their fellow aficionados? Once we looked, we found them everywhere: A woman who devotes her time to going to college, cashiering, and growing matchless African violets. A high school junior who struggled to produce the perfect lemon cookie. An entertainer who more than fulfilled his childhood dream of mastering the yo-yo. They and the five others on these pages are just a handful of Texans who stand tallest in their fields, and we tip our hats to them.

These unassuming winners popped up all over the state. Two national societies put us onto champs, as did hobby shops and gung ho hobbyists themselves. One person in tiny Hallettsville tipped us off to three winners. The budding chef was brought to our attention by the Pillsbury Company (which added that Texans are always Bake-Off finalists).

Meeting these folks, you might not suspect they’re champions. The guileless visages of two good ol’ country boys mask the keen minds of the state’s Forty-two kings. The dog breeder works full time to raise basset hounds with pedigrees purer than yours is. The accountant is a putt-putt whiz, and the airline budget manager is a fiddler who can cut loose and play with the best of them. In fact, he is the best of them. So are they all.

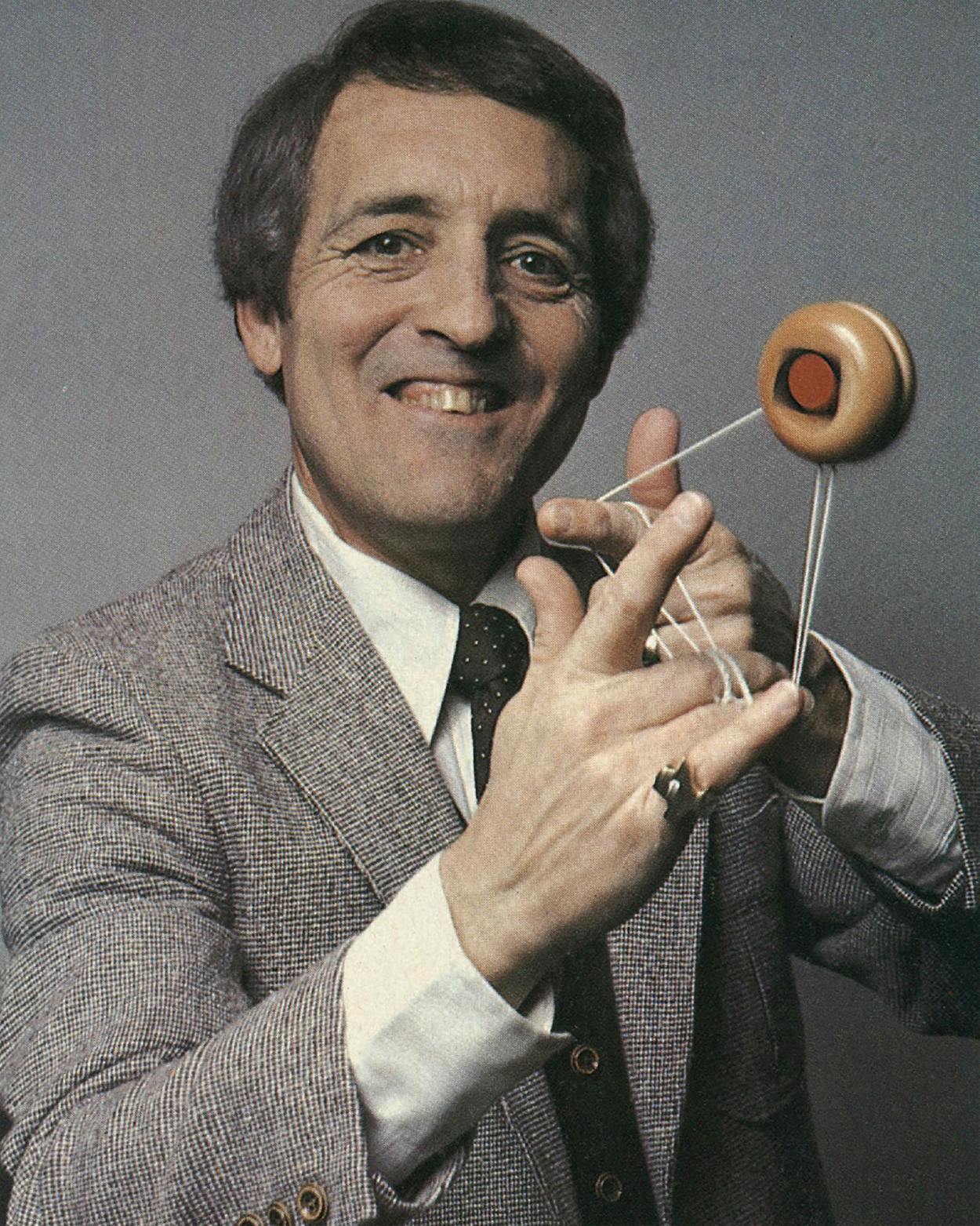

The Way to Unwind

Bunny Martin, 47, entertainer, Belton: “I’ve held the world championship yo-yo title for thirty years. I won it in 1951 in Toronto, Canada, and that was the last such contest ever held. At the time I was sixteen. The prize was $2500, and I thought I had the world on a string, if you’ll pardon the pun.

“I’d been hooked on yo-yoing since age eleven, when I skipped lunch one day and used the 25 cents to buy my first yo-yo. Back then the toy companies sent pros around to do exhibitions with yo-yos, and I followed one of them around for days to study his technique. He finally noticed me and had me do a little bit for him, and he said, ‘Hey, you’ve got a good snap to your wrist.’ Well, then I was really obsessed. I started practicing six to eight hours a day, and pretty soon I was really good.

“I have a collection of all sorts of yo-yos—some with rhinestones, one with bells, even a sterling silver one—but the best yo-yos are made of maple. I have about 250 maple yo-yos in my personal stock. Plastic yo-yos are all right, but none of them can compare with maple. It gives you the greatest control.

”There are thousands of yo-yo tricks: some elementary ones are Walk the Dog, Eating Spaghetti, Rock the Baby in the Cradle, Around the World—everyone knows Around the World. I can do it backwards with one hand and forwards with the other at the same time. The tough tricks are the ones like Man on the Flying Trapeze, Spider Web, Reach for the Moon, Brain Twister, the Atomic Bomb, and the H-bomb. I invented that last one. I also invented a trick I call Fireworks With a Yo-yo: I throw the yo-yo so it ignites a match held between someone’s teeth. To my knowledge I’m the only person who’s ever done that.”

African Violet Queen

Bebe Glaser, 35, student and cashier, Houston: “My African violets have won best of show awards at competitions held by the African Violet Study Club, the Houston Gesneriad Society, and the Houston council of the African Violet Society of America. Plants are scored according to a point system; 100 is perfect. I’ve never had a 100-point plant—is nature perfect?—but I’ve had 98s and 99s. I’ve also won collection awards, but my collection is down now. I used to have three hundred plants, but now I only have a hundred or so.

“African violets really are from Africa, so they prefer warm days and cool nights—maybe 75 degrees during the day and 10 degrees less at night. One secret is to put them under fluorescent light; they grow five times as fast that way. Most beginners overwater their plants. That’s the most common mistake; it causes the roots to rot. Or novices will overfertilize. African violets are like children: when they need something, you make sure they get it, but you don’t want to give them too much of anything.

“There are literally thousands of varieties of African violets. One of my very favorites is the variety called Houston, which was developed by my friend Billie Golla. It’s variegated—that is, two-tone—in shades of light and dark orchid with dark green foliage. It’s beautiful—but then, all African violets are.”

Putt Up or Shut Up

Robert D. Smith, 27, CPA, Dallas: “I’ve been playing putt-putt for half my life now, ever since I was thirteen. Altogether I’ve won about thirty tournaments on the state and national levels, including two national championships in 1972 and 1974. If I included the times I’ve won locally, there’d just be too many to count.

“I started playing putt-putt just for fun, but by the time I was sixteen I was playing competitively. That’s what sets putt-putt off from miniature golf, besides the fact that putt-putt courses don’t have giant animals like gorillas or dinosaurs to shoot through. Putt-putt is competitive. The people who play it play to win as much as to have fun. There’s skill involved, a much higher level of skill than in mini golf.

“I don’t think there’s really a secret of how to play putt-putt. Eye-hand coordination is most important, but just like anything else, you’ve got to work at it. The first time you walked out on a putt-putt course you’d probably hit the ball too hard—the playing surface is slick compared to a golf course green. But you’d develop a feel for it.

“I don’t get to play as much as I used to—I only played in three tournaments last year—but I still love it. To some people, putt-putt is no big deal. But if you like it, you’re hooked.”

Rocks Around the Clock

Joe F. Steffek, 67, retired farmer, Hallettsville: “I guess I prefer Forty-two to straight dominoes. There’s less figuring to do, and you pretty much know what you’ve got as soon as you pick up your hand. Forty-two depends a lot on luck. So I don’t know as I’d say we’re good at Forty-two; we’re just lucky. At the tournament there were 88 players, but we managed to hold out the full time—about twelve hours—and only lost one set. At one point one rock—domino—would’ve set us if my partner hadn’t had it, but he did. Oh, you’ve got to know what you’re doing, all right, but you’ve got to have that little bit of luck too.”

George Bujnoch, 52, industrial castings supervisor, Houston: “There’s not much to do in the country at night except play dominoes. It’s a good way to keep busy and have a good time, too. There’s two types of dominoes, you know—straight dominoes and Forty-two. There have been state championships before for straight but not for Forty-two; the tournament we won in March was the first ever. Joe’s my brother-in-law; we’ve been playing together for twenty years. That’s probably part of the reason we won. If you’ve played with a person long enough, you just get to know the way they play.”

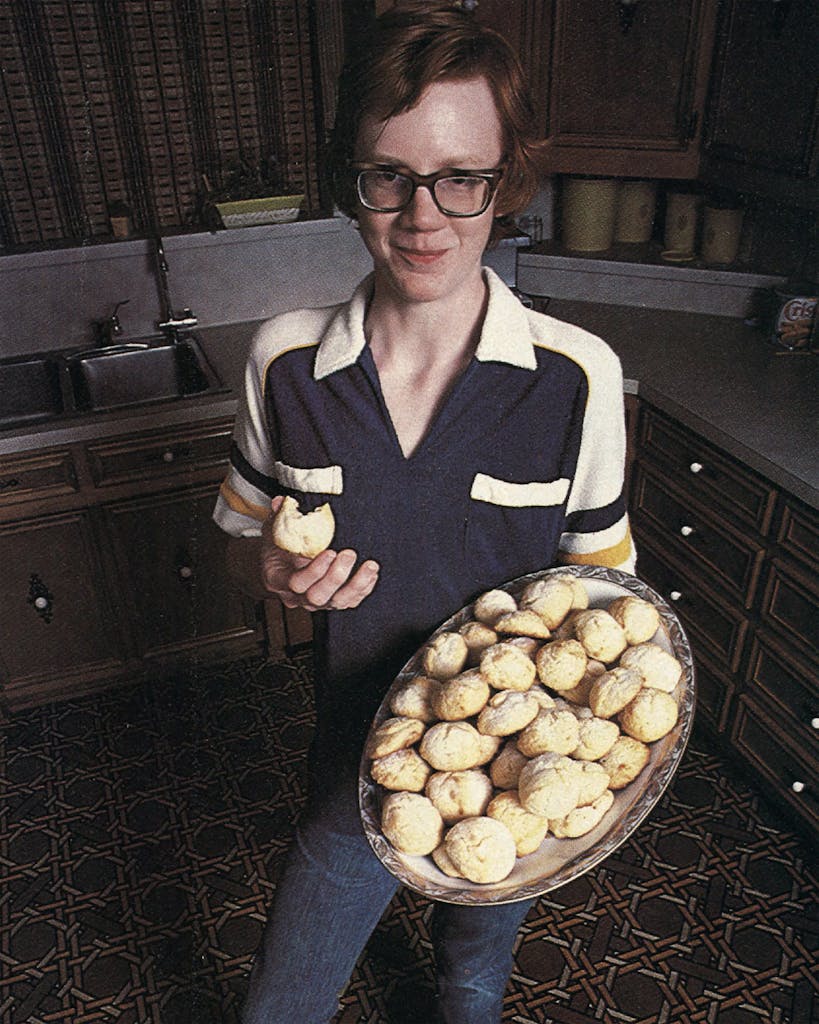

Student, Baker, Lemon Cookie Maker

David Cato, 16, student, San Antonio: “I was the youngest finalist in the last Pillsbury Bake-Off, in 1980. There are only one hundred finalists nationwide. My recipe was Lemon Light Drop Cookies; it has lemon yogurt in it. I adapted it from another recipe, and I must have made it ten times before it came out right. I still make those cookies occasionally, but not as much as I used to. I got a little tired of them. Sometimes I put together a main dish, but desserts are my favorite thing to cook.

“I first got interested in cooking by watching my mother cook and helping her in the kitchen, and finally I decided to try my own hand at it. I’ve been doing it for quite a while. My mother was also the one who suggested I enter the Bake-Off—she had entered it once but hadn’t placed.

“No, I don’t get teased much about cooking. Things are changing. In the cooking classes at my high school a large percentage of the people are boys. There were some other guys who were finalists in the Bake-Off too, so I was not alone. But I don’t know why anybody wouldn’t want to learn to cook; the good thing about it, after all, is that you get to eat when you’re through.”

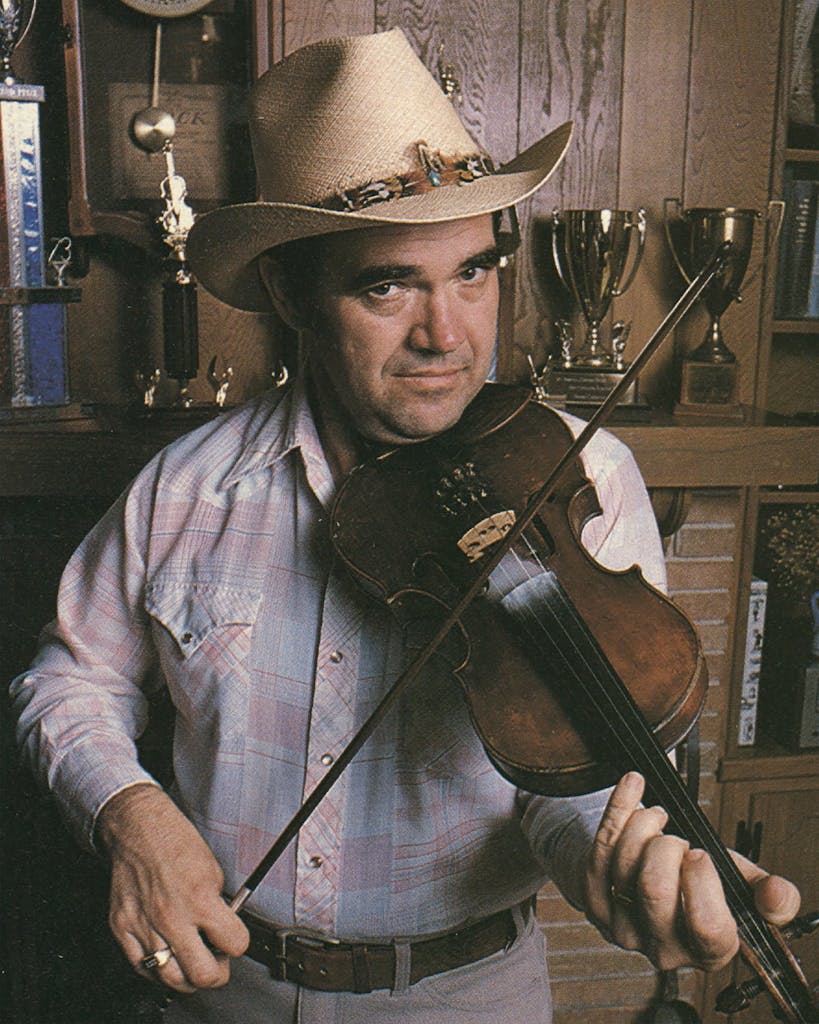

Taking It on the Chin

James Chancellor, 38, budget manager, Richardson: “I was the state champion and world champion fiddler in 1980. The contests for those two titles are held in Hallettsville and Crockett, respectively, and I won them both. I play under the professional name of Texas Shorty—I’m not that short, really, I’m five nine, but I never did try to shake the name.

“My dad got me started in music when I was six. One day he came home with a guitar and a mandolin and told me and my brother to choose one. I learned to play both. I didn’t start playing the fiddle till I was twelve, when I met a man named Benny Thomasson. Benny was a fine fiddler. He’s the one who taught me about old-time, breakdown fiddling. That kind of music doesn’t come printed; you can’t walk into a store and buy a piece of sheet music and learn it. It’s passed around from fiddler to fiddler. Two years after I met Benny I won my first contest, and then I began to win a goodly number of them.

“The World Fiddle Festival in Crockett used to have a rule that if you won three years in a row you had to retire as an undefeated champion. That’s what happened to Benny Thomasson—he was that good. Well, when I was sixteen, I entered that same festival, and I won. Then I won the next year and, sure enough, the year after that. So I had to retire too—undefeated at eighteen. That was twenty years ago. When the festival organizers decided to let undefeated world champions participate again, I entered the contest one more time—with a little bit of nervousness, because there’s a certain security in being an undefeated champion. But I won again. And this year I’ll shoot for two in a row.”

A Woman of Breeding

Beverly Stockfelt, 49, dog breeder, Fort Worth: “My husband, Lee, and I own 23 basset hounds—at last count. The American Kennel Club has confirmed four of those as champions. That means that each dog won a certain number of points and defeated a certain number of other dogs at specialty or all-breed dog shows. One of my winners is Champion BevLees Davy Jones. He just won best of breed at the Dal-Tex Basset Hound Club Specialty Show. I was really pleased. Davy comes from a long line of champions—his great-great-grandfather, Champion BevLees Tom Sawyer, is also an AKC champion.

“We breed our dogs carefully, trying to produce offspring that are a little bit better than both parents. We start to train them very early. I started with Davy when he was about three weeks old, teaching him to stack—that means assume a show pose—and to walk on my left side. I keep him in shape by walking half a mile a day with him—that is, if I’m up for it; he’s always ready to go.

“We got interested in bassets in 1961, when we took one from some people who were going to send her to the pound otherwise. They’re warm dogs—adaptable and lovable. Raising bassets is a full-time hobby. It means a lot of heartache; you get so attached to them, and sometimes you plan three years in advance for a certain breeding only to get no show material out of it. Raising these dogs also takes a lot of money. I’d say we spend $6000 a year, between upkeep for the dogs and the expense of shows. We were lucky to find an old greyhound farm a while back. It already has the kennel buildings and the dog runs, so we have room to keep all the dogs we want.”

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Dogs