This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The road map that the State Highway Department provides free to a million travelers each year is a princely product in a competitive field. It is loaded with special features: distance and population tables, city schematics, park listings, and topographic illustrations. It is bigger than other maps of Texas, and it includes more miles of highway than other maps do. Because it is the work of craftsmen, it does contain a few errors. I should know. Last year I drove every inch of road on it.

But I can’t bear to lay eyes on that map anymore. I have come to think of myself as the man who appeared in television ads at holiday season some years back. His pale skin turned phosphorescent green, his abdomen swelled like a balloon, and he groaned, “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing!” Nobody else has ever driven all those roads, and if my advice is heeded, it will be a long time before anybody else tries. I enjoyed myself and I learned a lot while on my National Tour of Texas, but after gluttony comes dyspepsia.

The trip was one of those adventures that are a writer’s dream. The idea was mine, and it was born out of a patriotic fondness for Texas and from a deep curiosity about its fate. I also wanted to get out of the cities, away from the office and the fetters of settled life. Or I thought I did. I didn’t come home on weekends, I didn’t slow down on Sundays, I ate Thanksgiving dinner (two hamburgers) at the McDonald’s in Sweetwater (or was it in Roscoe?), and most of the time I traveled alone. Telephone calls and letters from friends kept me abreast of their lives, but I had trouble keeping pace with myself. I visited almost every city and town in Texas—yes, I have been to New York, London, and Paris, Saturn, Mercury, and Mars —and I’ve got a book of postal seals to prove I was there.

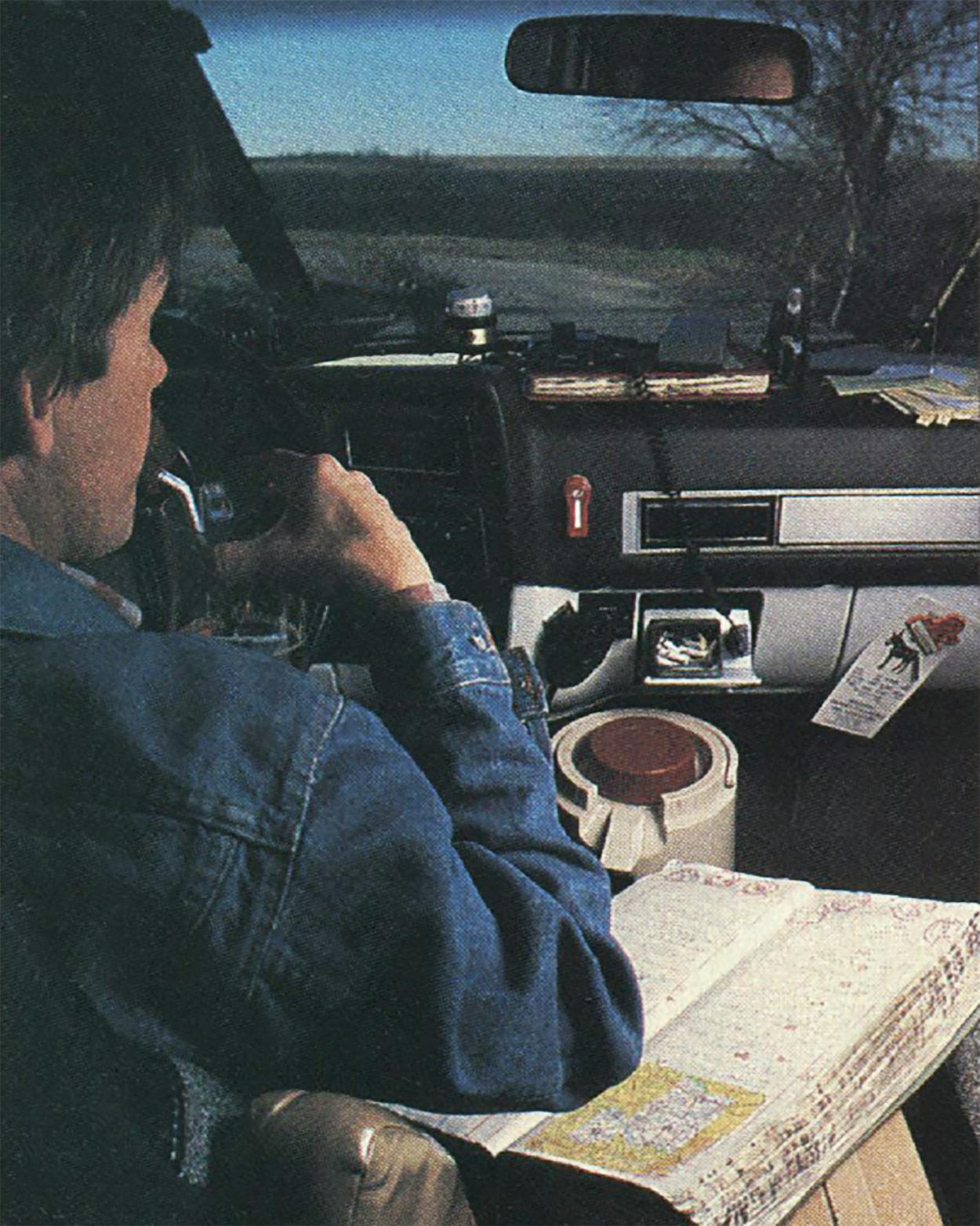

At the beginning of each week the American Automobile Association sent me a list of the roads I was to drive and the order I was to follow to get the job done. Interpreting the itinerary was like reading real estate listings in classified ads: “SH [State Highway] 214 N [North] to FM [Farm-to-Market Road] 145, appx. 11 mi.; FM 145 E to FM 1055, 18 mi.,” and so on. Though the schedule was doled out in daily portions, it was more demanding than I had anticipated. I saw so much of Texas—103,000 miles’ worth—that my memory can’t hold it all. If you mention your hometown to me, I’ll probably nod knowingly; I must have been there. But without help from the map’s index, I still won’t be able to tell you where Louise, Lydia, Margaret, Vivian, or Diana is.

If I had it to do over again, I wouldn’t flinch. The trip was worth taking—but only once. It schooled me in a footloose kind of life, filled my eyes with scenery, taught me more Texas trivia than anybody needs to know, and gave me new intimations about our state. It also put me out of the daily reach of my superiors, and as in any other business, there’s no way to overestimate the restorative value of a thing like that.

Off and Running

I began the trip on a cold and windy January 1, 1987, just outside the gates of the Cotton Bowl. By nightfall I was well on my way to the Rio Grande Valley, where I spent the first of many weeks in a motel, exploring grapefruit groves and Winter Texan camps.

Folk wisdom tells us that motels are an invention of the age of speed, but my experience has led me to doubt that view. Of course, motels are the quickest route to a shower and bed, but they are more than merely resting places for the human species at night. They’re menageries. On the fourth or fifth night of my stay in Harlingen, I was awakened at sunup by the baying of a basset hound in the room next to mine. I soon learned that the attitude, if not the policy, of motel managers is that the guests who rent the rooms also buy the right to host visitors of their own, regardless of sex, marital status, or pedigree.

A few weeks later in Laredo a caterwauling tom robbed me of my sleep, but I soon quit counting the nights I was sacrificing to crooning animal kings. I began to notice the Kafka-esque ritual by which guests legitimize their pets as visitors in motels. From ribbon-cutting day, motels post signs that say “No pets allowed in rooms.” So at registration time guests conveniently fail to declare their livestock. All the same, every evening just after sundown, guests and their pets promenade on the motel’s parking lots and greens, where the animals perform unspeakable acts in the public view. I learned that it is useless to protest, because pet owners will ignore you. This nightly ritual is so well established, I concluded, that it must have originated very long ago indeed. Motels, I’m convinced, were invented by Noah.

Because pets are a plague at all motels, motel quality must be judged by other standards. Bad motels are all of a personality type I came to know well. A bad motel’s switchboard and office—site of the only ice machine and the motel’s central thermostat—close at ten in the evening. Although the checkout time is eleven, the maids start playing reveille on hollow-construction doors (steel congas, I call them) at seven in the morning. Its bathrooms are supplied with a plumber’s friend. Its profits will soar, the manager believes, just as soon as he harvests the pharmaceutical molds growing in the carpet of the rooms.

At the same time, good motels in Texas number in the thousands. The chain and franchise motels that line our major highways are usually safe bets, quiet and clean—except during senior-trip week and cur-feeding time. But at independent, out-of-the-way motels, it’s important to know how to predict trouble. If there’s a single secret to spotting a slipshod motel operation, it’s this: ask to see the room before renting, and don’t forget to inspect the towels. I learned that it didn’t pay to stay at motels that had towels that wouldn’t span my thirty-inch waist. Tiny towels are a tip-off that the management is probably pinching pennies on roach control or air-conditioner maintenance. Even at motels where the towels pass the test, it’s wise to inspect the cars in spaces adjacent to yours. If there’s a bag of Gravy Train on the back seat, you would probably be happier in a room farther down the hall.

Kountry Kafes

Farm-fresh foods are part of the legendary lure of the back roads. That’s why our highways are lined with eateries with names like Country Cafe, Country Kitchen, and Country Cookin’. (To heighten our expectations of rusticity, the letter c is sometimes replaced with the letter k, as in “Kountry Korner.”) I found dozens of good hometown restaurants, among them Memo’s in Marfa, the Cold Water Cattle Company in Coleman, and the Cowboy Cafe in Canyon. But nary a one had the word “country” in its name. “Country” is a come-on; most “country” cuisine is supplied by big-city restaurant purveyors. Factory-made frozen french fries, for example, are now de rigueur across South, East, and Central Texas. Because local recommendations can’t be trusted and guidebooks are spotty in their listings, finding a good country restaurant is a matter of pure luck. But there are ways of recognizing a bad country cafe once you’ve entered its doors—and there’s a protocol to follow until you can get out.

A bad country cafe is one in which Granny entertains her offspring. Grandbaby, a howler passing through the terrible twos, periodically dashes into the kitchen where Mommy, the cook, wipes Baby’s face and leads her by the hand back into the dining hall, stopping along the way to discuss Baby’s vigor with the waitress. If your coffee hasn’t been served or your pancakes turn to charcoal during this scene, don’t mention it. If you do, you’ll never be served because you’re not a regular customer, and your disinterest in Baby’s development shows that you’ll never be one.

A bad country cafe is one that you enter at 5:45 in the evening, fifteen minutes after the town’s divorced men come through the door. Don’t show impatience if service is slow. If you’re female, your restlessness will be taken as a personal snub. If you’re male, one of those fellows is bound to recognize your unease as the mark of a man associated with the fellow’s ex-wife.

The drawing card of a bad country cafe is its television set, not its food. Don’t take your eyes off of it. If you do, people will think that you’re bored with their town.

At the bad country cafe’s salad bar the star attraction is canned fruit cocktail. Use it to sweeten your tea. That white substance in the sugar containers has already turned to stone.

A bad country cafe serves machine-breaded hamburger patties as chicken-fried steak, and the prices on its menu are exorbitant. But the washboards and mule-train tack that adorn the walls didn’t come cheap, and besides, where else are you going to park your semi-trailer truck? The country cafe is probably the only restaurant in town, and since the owner hasn’t seen you before, he already knows that you won’t be back.

No matter what, be polite. A bad country cafe is the last place in the world where you want to raise a ruckus about service or cuisine or anything else, because a lawman is always there. The cafe gives him free coffee and a public office space, and he doesn’t take kindly to disturbances at work.

The Devil’s Workshop

The pleasures of extended travel are not corporeal. Travelers, as a rule, don’t eat well or sleep well or get much exercise. Creature comforts—a bowl of oatmeal at night, an easy chair, a familiar old movie on tape—are hard to come by, and after a while, vice takes their place. I found myself smoking more cigarettes than ever, and if I had thought that I could face the hangovers, I would certainly have become a nighttime drunk. Good health is a requirement for travel, but the traveler’s malaise, a result of loneliness as much as motion, works against it. Three times on the road I succumbed to the flu. Each time, I pulled into the shell of my motel room and fed myself fruity soft drinks. Sleep and time made the misery pass.

Keep on Truckin’

The payoff that justifies a trip like mine and makes it worthwhile is familiarity with Texas. I developed a truck driver’s wisdom about the state. I can tell you, for example, that it takes less than a day to drive from Boston to San Diego or even from Egypt to China. I know the difference between Center and Centerville, Industry and Commerce, Best and Veribest. I could see that cotton has gone from Cotton Center in East Texas’ Fannin County to Cotton Center in Hale County on the South Plains. I visited both Tarzan and Ben Hur, and I know that the billboards in Forney, Nacogdoches, and New Braunfels—each proclaiming its town to be “The Antique Capital of Texas”—can’t all be true. I sent Chester a postcard from Chester and Fred a postcard from Fred. I became one of the few Texans outside of Briscoe County who know how to pronounce the name of the town called Quitaque. If you want to know, you’ll have to go there yourself.

I learned new ways to distinguish not only between towns but also between the regions in which they lie. You know you’re in South Texas, for example, when automatic-teller machines ask whether you would rather communicate in English or Spanish. If signs beside the road warn you of “Falling Rock,” you’re probably in the Trans-Pecos, and if they read “Low Water Crossing,” you’re probably in the Hill Country. Guadalupe Pass is the only place in Texas I noticed where wind socks warn motorists of gales, and the Red River counties are the only place where women habitually wear bonnets. You know you’re in East Texas when you see convenience-store racks stocked with welders’ caps. If you become aware of both the sun and the moon in the noontime sky, you’ve probably risen to the High Plains, where the sky dominates the landscape. I learned enough from roadside signs to know that “Brine” puts you in the Permian Basin, “Bush Hogging” means southeast Texas, and “Stripper Parts” is the cotton belt of the South Plains. Though I bought postcards showing such scenes as tobacco fields near Pleasanton, trout-fishing near Stratford, and snowmobiling around Hamilton, I found out that those images had no basis in fact.

The Shutterbug in Me

Like any tourist, I carried a snapshot camera. I took pictures of, among other things, 252 of the state’s 254 county courthouses—those at San Antonio and Belton slipped from my mind—and in the process, I filled a notebook with casual observations about civic architecture and monuments.

I noticed that in three Texas towns—Slaton, Childress, and Dumas—monuments to veterans were crowned with eternal flames. But all three flames have gone out. Designers in Plainview were more farsighted; their memorial is topped by a flame of brass. The miniature Statue of Liberty on the Capitol lawn, I discovered, is only a mail-order clone; identical statues stand in Port Arthur, Forney, Midland, and Big Spring. The Alcoholics Anonymous office on the Childress County courthouse grounds was a puzzlement to me: do county judges drink that much?

I’m sure that militant atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair would head for federal court if she knew that there’s a chapel on the grounds of the King County courthouse, that a Nativity scene graced the Montague County courthouse lawn at Christmastime, or that on the Hill County square is a sign saying “See You in Church on Sunday.” The courthouse adornments I liked best were those that symbolized the area’s economic pursuits: the spinach-eating Popeye in Crystal City, the pump jack at Andrews, the fiberglass milk cow at Stephenville, the stuffed Longhorn at George West, and Yoakum County’s first bale of 1987 cotton, on display at the courthouse in Plains.

Dozens of the courthouses are striking, especially the Romanesque-revival-style ones in the Hill Country and the foursquare hulks with neoclassical details between I-35 West and U.S. 281. But one stands out as an eyesore. The ugliest courthouse complex in Texas is in Canyon, the seat of Randall County, in the Panhandle. The original courthouse, a three-story red-brick structure erected in 1909, is flanked by low-lying office buildings built in the budget-minded, functional style of the early sixties. The new offices blocked the view of the courthouse, and after they were occupied, the old building was abandoned. The old courthouse sits in its square today, awaiting restoration or the wrecking ball.

Higher Truths

If I had any grand goal for the National Tour of Texas, it was to find answers to two questions that have nagged me for years: What is Texas? and Who is a Texan?—questions about qualities of character, not about political lines or vital statistics. I didn’t find definitive answers, but I did come closer, if only by confirming a trait that others have noticed. Most Texans are a history-bitten people. I came upon this realization when, after months of driving, it dawned on me that whenever I stopped to chat with someone about his hometown, the first thing he invariably said was “Well, we’ve got a lot of history around here.”

The claim was patently false over nearly half of the surface of the state. The High Plains were largely unsettled until the twenties, and for practical purposes, the Trans-Pecos and much of northwest Texas is still uninhabited today. With the exception of a half-dozen towns that trace their origins to Indians or Spanish colonists, civilization in Texas is less than two hundred years old; on the scale of history, Texas is a babe. Our picture of ourselves as a historical people is composed partly of longing, partly of pretense, and only partly of fact.

Yet most counties in Texas have a historical or heritage museum, and almost half have two or more. The sesquicentennial produced a spurt of museum openings, it is true, but the museums don’t seem to be a fad. Most of them have attracted a corps of retiree-volunteers, and I didn’t hear of any museums that are in danger of closing anytime soon. Despite the inevitable and innumerable invitations I received, I didn’t tour many of those museums because, after seeing a dozen of them, I began to feel as if I had seen them all: most wagon wheels look alike.

In several towns the love of history has reached what I considered to be admirable heights—in Crockett, for example, the historical society had courthouse offices and, what’s more, reserved parking spaces—but in others it seemed to have passed the bounds of reason and become a sacrifice. Nordheim (population: 369), Meadow (population: 571), Moran (population: 344), and Gail (population: 189 and the seat of untamed Borden County) all support museums. Crowell (population: 1,509) is host to two heritage showplaces, one of them devoted to the history of local fire-fighting units.

For better or for worse, the widespread enthusiasm for history is not universal. South Texans, whose ties to Texas often antedate independence, hardly participated in the museum-christening rush, and the big round rock that gave Austin’s most-bustling suburb its name sits at the roadside, unprotected and unmarked, its base resting on the muddy bank of a stream. So a sense of history can’t be the essence of Texanhood.

Texans differ so much that the questions I carried—the intellectual baggage of my trip—sometimes seemed to be useless burdens, best left behind. Most other Texans act as if they have found answers to those questions, though none of us has articulated them. Supporters of George Bush, for example, argue that he’s a Texan—when he wants to be—because he launched his career upon our soil; success in Texas constitutes Texanhood, these people apparently believe. Detractors say that Bush isn’t a Texan and can’t ever be, because he spent his formative years in the Yankee North; if that argument holds, where one spends one’s adolescence is the measure of Texanhood. The question of Texanhood is controversial, and a sure standard is hard to come by. Is country musician Jerry Jeff Walker a Texan because he chose Austin over New York? If he is, did Texas Observer publisher Ronnie Dugger forfeit his Texanhood when he left for New York? And what about poor Bum Phillips, who had no choice but to leave Houston for New Orleans? If George, Jerry Jeff, Ronnie, and Bum are Texans all, as some maintain, then verily, Texas is already the nation’s most-populous state.

Most Texans, whether they like his administration or not, regard Bill Clements as a Texan of the classic sort and would extend that honor to him, even if they were to learn that he had been born in Pennsylvania. But brashness and a tendency to be absurd haven’t won similarly begrudging-but-charmed respect for black state representative Ron Wilson of Houston. And though Willie and Waylon have become Texas icons, only the Latin minority and a few Anglo music cognoscenti are acquainted with the music of Sunny Ozuna and Flaco Jimenez.

My opinion, after seeing the whole state and meeting its people, is that nothing ties Texans together except our insistence on remaining tied together. Texanhood does not exist in nature; it is made. And nothing strengthens it more than the prejudice of outsiders. The scenes I saw through my windshield certainly aren’t the stuff that binds Texans into peoplehood. North Texas is easily mistaken for Oklahoma, East Texas for Dixie, and the Trans-Pecos for the states to its west. The Hill Country isn’t Texas; it has more in common with rural Pennsylvania. Our history fails to unify us: El Paso was a Union fortress, and the German communities of Central Texas were hotbeds of Civil War draft resistance. Nor does economics provide ground for Texanhood. Last year, while Houston and the Permian Basin were sinking slowly, West Texas cotton producers were dancing in the rains, and Fort Worth’s defense industries were gearing up for a boom.

I’ve decided to do what other Texans do: I’ll define Texas as my Texas, the Texas I know and like best. Texas is a place where people don’t need traffic reports to find their way home, where they can hear passing trains in the night, where the question Where’s he from? is usually asked before the question What does he do? It is Texas under the plow, Texas at the sawmill road, Texas on livestock auction day—rural Texas, where all the lines on the state map go.

Hail, and Farewell

I completed my Tour of Texas on January 1 of this year by returning to the Cotton Bowl. As soon as I had dismounted from my Suburban, friends, readers, and reporters asked me what I planned to do in 1988. This year I’m going to get away from Texas. I’ll spend most of my time south of the border, in Mexico. How will I get there? Driving, of course.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads