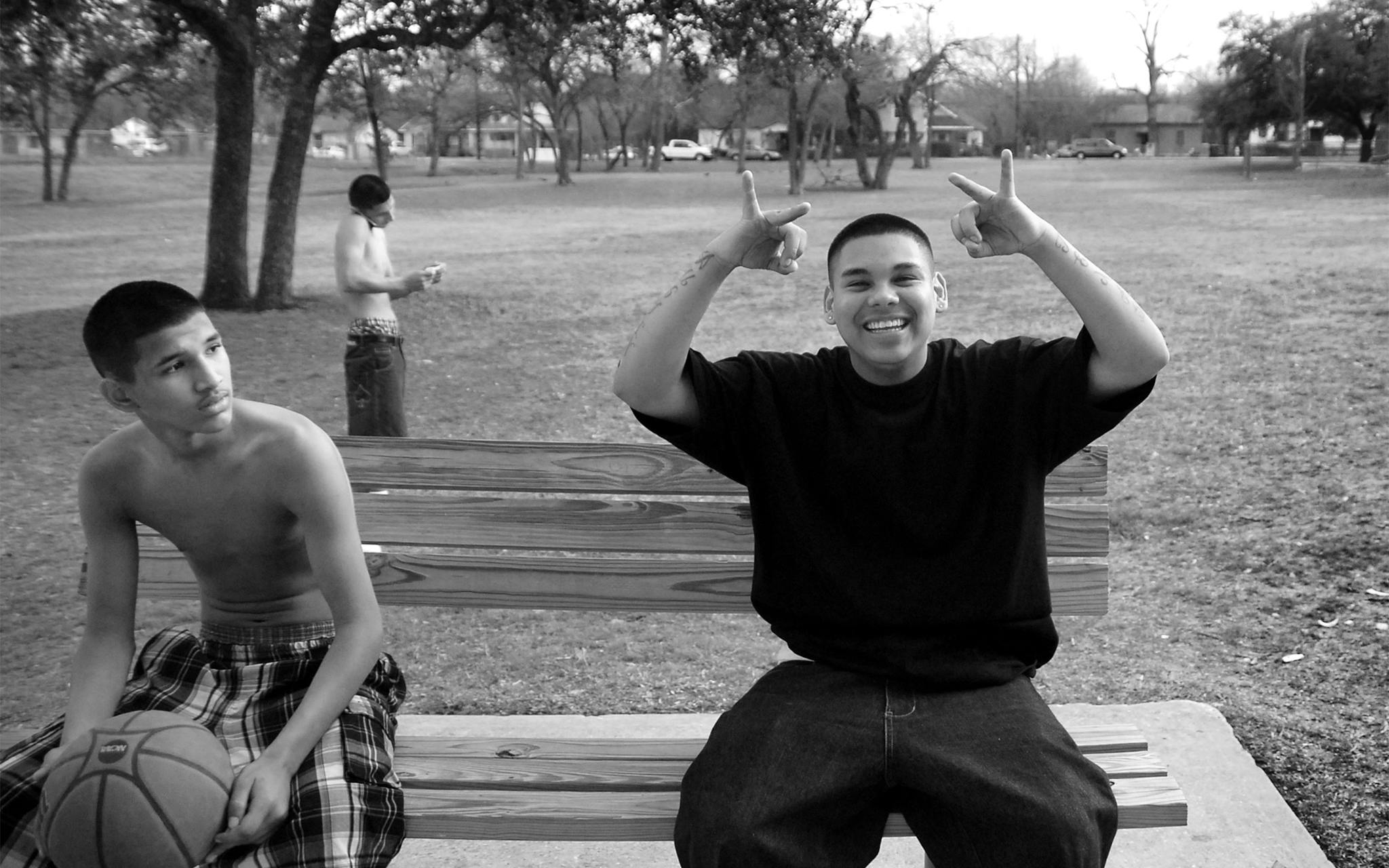

The first time I met thirteen-year-old Christian Martinez, he told me he was fifteen. He was an athletic-looking kid without a pinch of fat who wore a white tank top and sported the close-cropped fade common to East Austin Latino boys in the late aughts. He sat on a hillside bench in the dead center of the Booker T. Washington Terraces, one of Austin’s oldest housing projects, with a boy named Juan, whom I would never see again, and a pudgy kid called Big Boy, who never left Christian’s side.

When I explained that I was a University of Texas student working on a journalism project and wanted to ask him about life in his neighborhood, Christian was surprisingly eager to talk. As a steady February wind blew across our faces, he spoke for thirty minutes in a laid-back drawl that was clearly influenced in cadence and vocabulary by Houston rap.

Over the first five months of 2009, the last part of my senior year, I visited Christian’s neighborhood 43 times, taking photographs and recording interviews that would eventually become The Boys of Booker T, a multimedia project that chronicled the experiences of families whose fathers had been incarcerated, with a particular focus on young men.

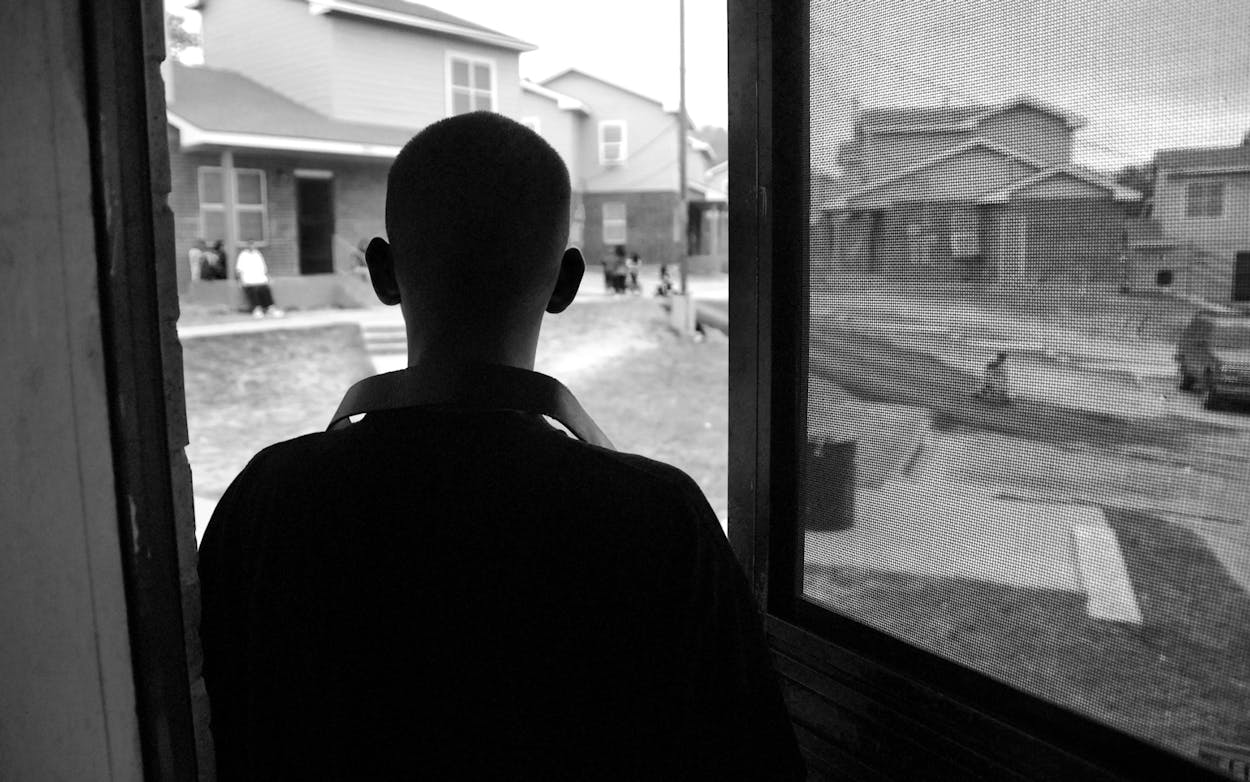

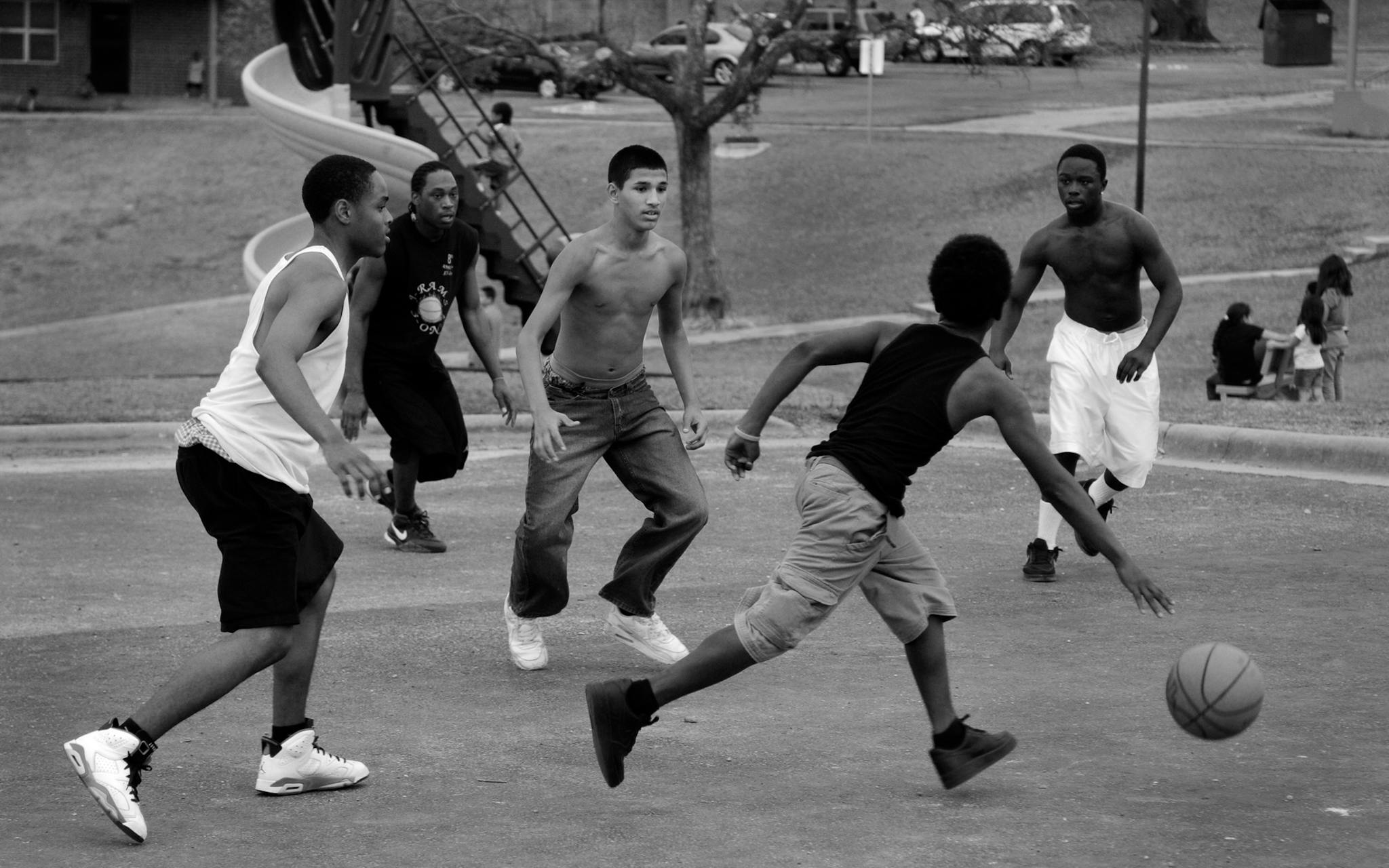

Booker T., a triangular cluster of government-subsidized apartments built on a steep slope in East Austin, was notorious in the nineties and aughts for drug dealing and gang activity. The boys I met in the 0-2, as they proudly referred to their neighborhood in the 78702 zip code, formed a tight-knit brotherhood but also found trouble waiting outside their screen doors. Josh Fabela, one of Christian’s closest friends, regularly attended church for a year and a half before he “fell off” into drugs and crime and landed on probation. “I’m over here smoking weed, doing stupid things that I shouldn’t be doing, but I don’t know—I still do ’em anyways because I feel like that’s who I am,” he told me in a 2009 interview. Isidro Cruz, whom the boys called Duck for the way his hair flipped out in the back, was the eldest of the group. He was a three-sport varsity athlete who worked hard in school but would still join his boys in a fight at a moment’s notice. “Everybody that lived there in that neighborhood, we all considered each other brothers,” he later told me. “We all lived by the rule ‘If they pick on you, they pick on all of us.’ ”

Arleen Juarez was Christian’s responsible big sister, trying to finish high school while tiptoeing through the minefield of her younger brothers’ misdeeds. She had a different pair of Air Jordans to match each outfit and a CD player spinning Lil Wayne, Usher, Eminem, and South Park Mexican. She said she was “happy I wasn’t a mom” and was falling head over heels for her new boyfriend, Joshua Rivera, who hailed from the nearby 2-1 but hung out at Booker T.

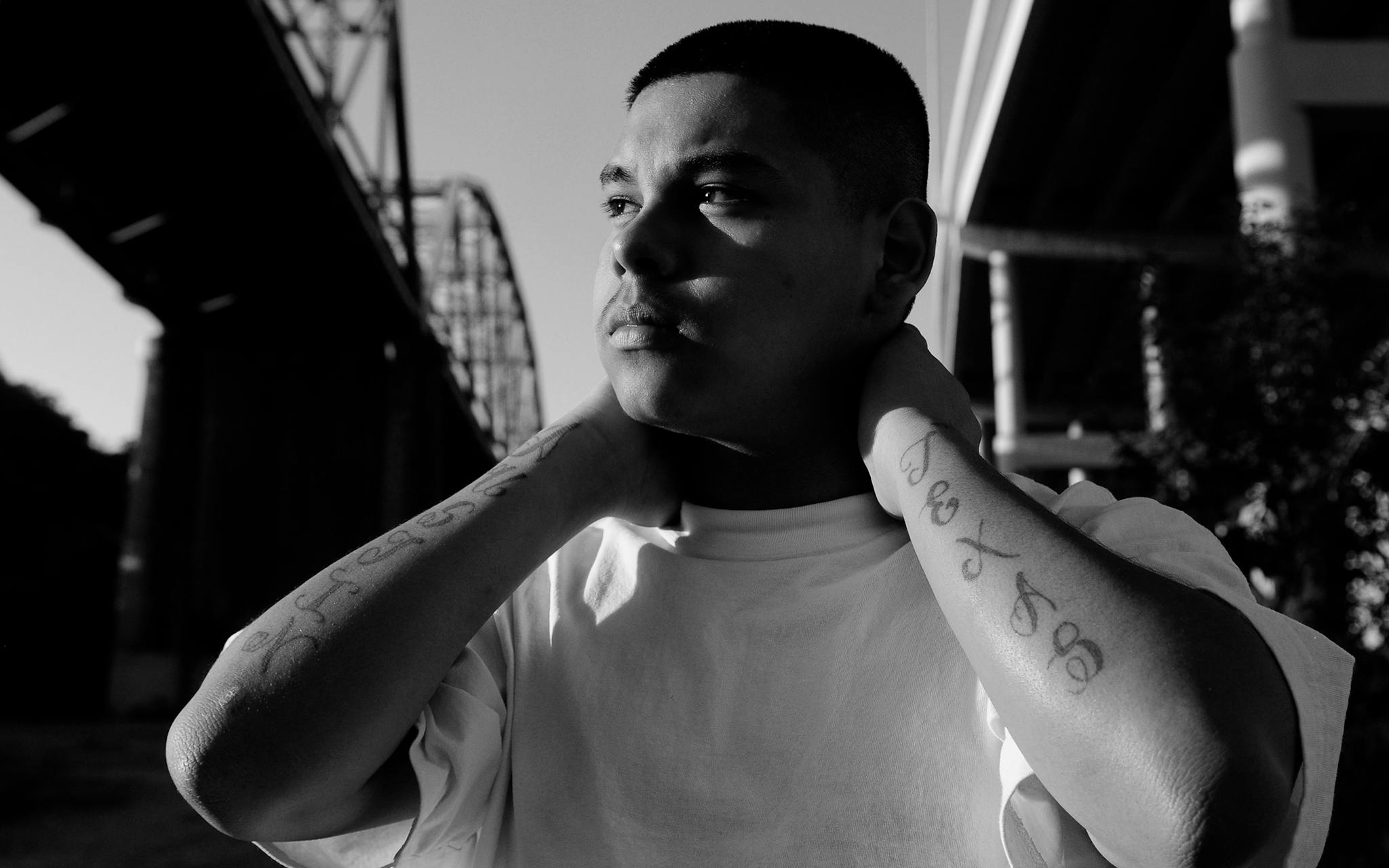

Of all the kids I met that spring, Christian stood out. His charismatic energy and confident air set him apart as a leader and a gatekeeper of the neighborhood. “He was the youngest out of all of us, but you couldn’t tell,” Fabela later told me. “You’d think he was the oldest.”

Like most thirteen-year-old boys, Christian was rarely serious when we spoke. A typical interview would be interrupted repeatedly by impromptu freestyle raps peppered with his favorite epithets: “nigga” and “bitch-ass nigga.” While some of the older brothers and dads of the neighborhood were affiliated with actual prison gangs, Christian and his friends were just testing the waters. They called themselves the “Texas Click” and had “T.C.” tattooed on their wrists next to three small dots arranged in a triangle, a common tattoo among Latino inmates signifying “mi vida loca.”

But while it sometimes seemed as if Christian and his friends were merely playing gangster, their crimes were no joke. They would steal cars and “hit licks,” kicking down doors to take laptops, cash, and other valuables from the fancy new homes popping up all over their rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. By fourteen, Christian had bought at least four cars using the money he made selling stolen merchandise.

But there’s honor among thieves, and Christian was in many ways the Robin Hood of Booker T., known for his fierce loyalty and generosity. “He probably had one of the biggest hearts out of all of us,” Cruz told me. He added that Christian would regularly use the profits from his break-ins to feed and clothe his neighbors. “There was times where we were struggling,” one neighbor, Demetria Acevedo, told me, “and he would just pop up with pizzas . . . and I would just look at him like, ‘Thank you.’ I never asked how he knew.”

At Kealing Middle School, Christian’s mischievous antics and constant boundary pushing drove his teachers crazy, but many of them secretly enjoyed the way his lively spirit broke up the monotony of class. “You couldn’t help but banter with him,” said Amy McMillan, a former Kealing counselor. “He was rarely sullen, and middle schoolers are sullen.” And he was thoughtful. Christian once invited McMillan over to his family’s apartment, where he surprised her with a cookie cake he’d bought for her birthday. “I don’t even know how he knew it was my birthday!” she said.

Christian once told me the only person he was scared of was God, and he’d never hit a lick with someone without first taking them to church. “He always made sure that on Wednesdays and Sundays he filled up a whole row,” his mother, Maricela Juarez, remembered. And when his ten-year-old neighbor Miguel Umanzor Jr., a.k.a. Big Boy, begged to join Christian on his burglaries, Christian wouldn’t let him. “He’d be like, ‘Go home’ or ‘Go over there and play with your other friends,’ ” Umanzor said. “He wanted better for me than he wanted for hisself.” Christian was his protector, Umanzor’s mother, Demetria, recalled. “When we first got to Booker T., Miguel was picked on by the other kids because he was the short, chubby kid, and Christian just took him in.”

Christian was also a promising boxer who trained at the Oswaldo A. B. Cantu / Pan-American Recreation Center, on Third Street, and had won several fights—both sanctioned and not so sanctioned. His lightning-quick hands, rivaled only by his tongue, had already earned him that most coveted currency of the 0-2: respect.

But behind his tough exterior and spirited personality, Christian carried about him a sense of injury typical of so many of the young men I met at Booker T. “They never felt safe,” McMillan told me. “I think Christian was constantly in [a state of] fight-or-flight.” She remembered watching helplessly one day as he stormed down the halls of Kealing, upset after a run-in with a teacher, slamming his fists into the lockers. “I saw an anger and fear that I’d never seen in Christian. I think he was scared of how out of control he was.”

Christian’s mother, Maricela, immigrated to Houston in 1982, when she was ten years old. Knowing no English, she was bullied at school and dropped out after getting pregnant at fifteen. She spent the next twelve years caught in a cycle of poverty and abuse and gave birth to five more children. Believing that, as an undocumented woman with little formal education, she had few options, she stayed with her children’s chronically incarcerated father, Jorge Martinez, until 2000, when he was sentenced to ten years for aggravated assault. Feeling “finally free” but struggling to make ends meet, she moved into Booker T. with her three sons and three daughters and took a job waiting tables at Capt. Benny’s Seafood, a kitschy boat-shaped restaurant off I-35 and U.S. 290 where she made $4.25 an hour plus tips.

She worried constantly about Christian. While he would often boast of his father’s fighting exploits and jokingly threaten to have his dad come by the next time I was around and “beat your bitch ass up,” his elder sisters recalled the longing for their father that he, as the youngest son, felt most acutely. And like so many other sons of incarcerated fathers, Christian saw few possibilities for his future other than criminality, the path his elder brothers Jorge and Lee had taken. “Christian has really fought between doing good and doing bad,” Maricela said. “But I think, at the same time, the three closest males in his life have gone in that direction, and even though I have been there to support him through everything, they just think, you know, that they have to follow that pattern.”

Despite his mother’s loving pleas and the valiant efforts of a cadre of school counselors, social workers, and juvenile probation officers, Christian continued to break the law and was, as Maricela put it, “looking to be put away for a long, long time.” She later told me, “I felt hopeless. I wanted to help him, but I didn’t know how.”

On the morning of April 11, 2010, a year after officially wrapping up The Boys of Booker T, I was driving from Houston to Austin along a bluebonnet-lined 290 with my fiancée when my phone rang. It was Maricela. Christian had been in a car accident around 3 a.m. that day on the very same stretch of 290 with his brother Lee and two friends. He and Lee were in the hospital in Houston, and while it seemed Lee might pull through, Christian’s prognosis wasn’t good. I immediately turned my Chevy Silverado back east and sped to Memorial Hermann Hospital.

As family and friends huddled in a dimly lit waiting room, Christian lay in a bed down the hall, his breath sustained only by the rhythmic pulsing of a ventilator. Christian had been asleep in the front passenger seat when the Nissan Maxima drifted off the highway and slammed into an SUV parked on the shoulder. The trauma of the crash left him with no discernible brain activity, and when Maricela arrived around 9 a.m., doctors were reviewing the grim test results and discussing organ donation, which Maricela eventually agreed to. Late the following night, she and Arleen accompanied Christian as he was wheeled to the door of Lee’s adjacent room. Though Lee was in a medically induced coma, Arleen gently lifted his hand to say goodbye to his younger brother. They were told they could go no farther, and they watched as Christian was taken into, as Maricela put it, “a surgery that I knew he was not coming back from.”

In the twelve years since Christian’s death, his family and I have stayed in touch. I got married and moved to Dallas, where my wife and I are raising our five children. Maricela and her children eventually moved out of Booker T., as did every other person featured in my original project.

In 2019, when I realized that it had been nearly a decade since the crash, I began reaching out to Christian’s friends and family about the possibility of revisiting their stories. A quick scroll of Facebook told me that several of the original boys of Booker T. now had sons themselves, a few of them around the ages of my kids. I wanted to hear from them. How did they look back on their time in the neighborhood? Did they miss it at all? How did it shape them as men? As fathers? How had losing Christian affected them?

Over the past two and a half years, I’ve taken ten trips to Central and South Texas, recording interviews and taking photographs to honor Christian’s memory and provide a deeper, multigenerational picture of the community he invited me into.

Arleen Juarez

Christian’s eldest sister’s sweetness—rather than the 0-2 tattoo her brothers sport, she has tattoos of a dinosaur and “a little horsey”—belies the difficulties she has endured. “I hadn’t, I guess, got hit by life,” she told me of the days when I first met her, a decade earlier. “So I guess I didn’t realize how, um . . . how ugly it could get.”

Arleen’s romance with Joshua Rivera was marked by tragedy early on. Christian was killed less than a year after they met, and two months later, Rivera’s mother died in a motorcycle accident. Devastated, he turned to PCP and other drugs to cope, and he began abusing Arleen. She stayed with him for six more years, giving birth to two children: a son, Diomani, in 2012, and a daughter, Hailee, in 2014. But the abuse continued, and they split up for good in 2016. Two years later, Joshua was sent to prison for assaulting Arleen and another woman.

Soon after, Arleen and the children moved into Maricela’s new residence, a mobile home in Kyle, thirty miles south of Austin, with her sister Marianna and Marianna’s children, Dan and Christian. On a typical morning, Arleen would quietly climb out of the bed she shared with Dio and Hailee, dress for work, and walk the kids to the bus stop before first light. Then she would get in her car and brave an hour or more of traffic to get to her job managing an apartment complex in Leander, north of Austin. Hours later, she would pull into the driveway after dark, just in time to check homework and get the kids bathed and in bed.

Two years ago, just as the coronavirus pandemic began, she and Marianna moved into the apartment complex Arleen managed. On weekdays all the kids live with their grandmother so that they can stay in their familiar school and Maricela can watch them while their mothers work. Though it hurts Arleen to see her children experience the same pain she did growing up without a father, she’s determined to see them break the cycle. She has taken parenting classes when her work schedule has allowed and spends time on the internet learning how to properly discipline her children. “My mom would just hit us, and I don’t think that’s, like, a great message,” she said.

The past decade hasn’t gone as she would have hoped—“not even close,” she said. But she remains resolved. “It makes me feel sad, angry, but it also makes me want to do better. A lot of the stuff that happened was not in my control, and I think I handled it the best I could. And yeah, it just makes me wanna push harder for the next years.”

Joshua Rivera

In 2009, when he was a frequent visitor to Booker T., Joshua Rivera stood out for his giant smile and his head of thick black curls. That’s the young man I remembered when he unexpectedly reached out to me in 2016 looking for life advice. Arleen had recently left him, and he was struggling. Two years later, he was locked up in Pam Lychner State Jail, in Humble, on a five-year sentence for domestic assault. In 2019 I sent him a letter asking if I could interview him, and he agreed. “I definitely have a story to tell,” he wrote, “and it might help save someone else.”

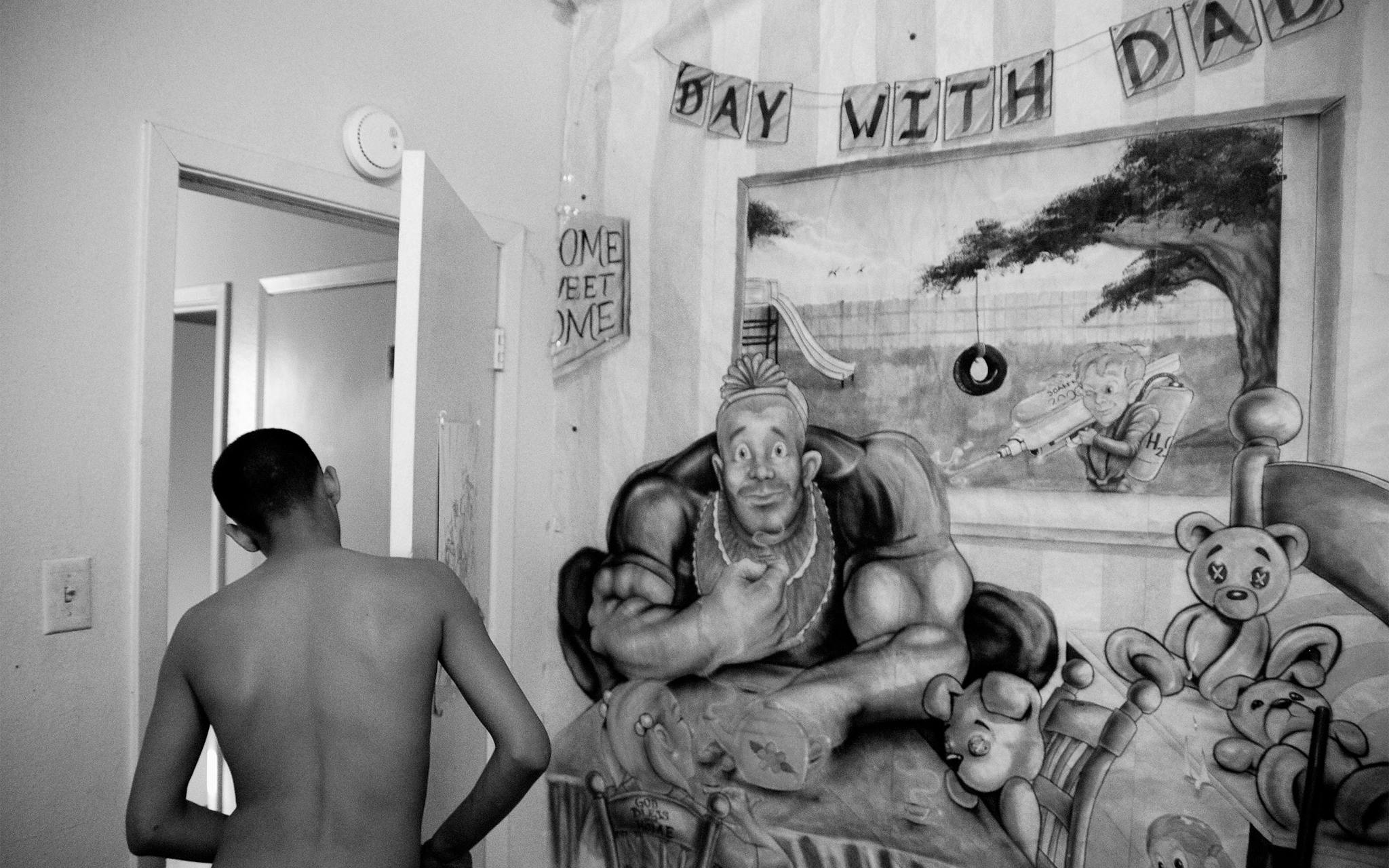

I met with him on a cold, cloudy January day under the watchful eye of a Texas Department of Criminal Justice communications officer in a visitation room sparsely decorated with a folding table, two chairs, and a mural of a pastoral landscape. Rivera sat by a window and candidly recounted his traumas and mistakes of the past decade—his father’s incarceration, his mother’s sudden death, his PCP addiction, and the violent eruptions that ultimately landed him behind bars. “I chose to do [drugs] because I didn’t wanna feel hurt and pain,” he told me. “And doing drugs led me to doing some things I wasn’t supposed to be doing.” He added, “It makes me wanna cry at times. It hurts that [my children] are living their daily lives, waking up, brushing their teeth, going to school, and I’m stuck in here. I can’t do nothing for them.”

Josh Fabela

Fabela lives with his wife, Regina, and two young children in southeast Austin in a quiet apartment complex far from the rough upbringing he knew at Booker T. “We all loved each other, but we hated the place,” he said of his friends and his childhood home. Today he breeds exotic pit bulls that he sells as pets and dreams of watching his son, Josh Jr., play baseball, basketball, or football for the Longhorns. “I wouldn’t ever let my son be raised like that,” he said of his youth, when he had to fight nearly every day to prove his toughness. “He’s gonna enjoy his childhood.”

Isidro Cruz

In 2016 Cruz left Austin and moved to the sleepy coastal town of Robstown, where his wife, Natalie, grew up. He was recently promoted to manager of the O’Reilly Auto Parts a mile from their one-story tan-brick house. Cruz points to Christian’s death as a turning point in his life. “What if I was there?” he said. “What if I was in that passenger seat where he died? And ever since that day, I never stole again. I never started any problems. It changed me.” He quit smoking and selling weed a few years back, and on his days off he attends church with his family, coaches his son’s baseball team, and takes the seven-year-old fishing on Corpus Christi Bay. “There’s nothing that I miss,” he said about his years growing up in Booker T. “I’m at a better place. I have God in my life. I have a beautiful family. I moved out of the whole city of Austin, Texas, because . . . there was nothing there for me.”

Lee Martinez

I never met Christian’s brother Lee when I visited the Booker T. complex a decade ago; he was “on the run,” as Christian would say. The first time I saw him, he was in that hospital bed, one room away from where Christian lay dying. Lee had been sitting behind Christian that night as they drove to Houston to sell stolen merchandise, and he too was seriously injured. His neck was in a brace, a hole had been surgically cut in the top of his skull, and his two little sisters, Marianna and Kassandra, were weeping at his side.

Lee was three years Christian’s senior and, like his father before him and his brother after him, has been no stranger to the prison system. Even at seventeen, at the time of the accident, he had a rap sheet that threatened to keep him forever stuck in a cycle of recidivism. As Christian once told me, “He tries to do good, but I don’t know why—he just can’t.”

When I reconnected with the family a couple of years ago, Lee, who’d made a full recovery from the accident, was sleeping on the couch of his mom’s small home, which she shared with Arleen and Marianna and their young children. Lee’s troubles with the law hadn’t ended, but he was doing odd jobs for a rural property owner and picking up his nieces and nephews from after-school care. One cold November day, I watched him prepare ramen noodles for the kids and dutifully help them with their homework. “I think it has made a big difference in Lee, being able to provide that way,” Maricela told me. Yet, not long after that conversation, Lee landed in jail once again, on domestic violence charges. He now lives with his girlfriend and their infant daughter in North Austin. The rest of the family keeps their distance from him while still helping to care for his child.

The tenth anniversary of Christian’s death came early in the pandemic shutdown, and there was no formal observance planned. I drove down that morning to the cemetery where he’s buried to see who might show up. At 1:50 p.m., Lee pulled into the parking lot and walked quietly to the graveside. He wore camo cargo shorts, a black Nike shirt, a brand-new Houston Texans cap, and an ankle monitor not so subtly hidden under black Nike crew socks. He was alone. He pulled out a portable speaker and played some rap songs. Against that soundtrack, he spent nearly an hour painstakingly clearing the weeds from Christian’s grave, pulling up grass to form an “02” in the dirt, and carefully crafting the words “MISS U” and “LEE” out of small twigs. As rain began to fall, he silently stared at his handiwork and the temporary nameplate that still marks his brother’s grave.

Dan, Diomani, Gordo & Hailee

While Arleen’s and Marianna’s children have grown up with incarcerated fathers, the chaotic realities that their mothers endured at Booker T. have faded from their lives, like the picture of Christian that hangs in the hallway of Maricela’s home, in Kyle.

Arleen’s seven-year-old daughter Hailee can often be found bounding across her grandmother’s living room, her head exploding with the thick black curls she inherited from her father. Hailee’s ten-year-old brother Diomani is a gentle soul who likes to play video games, read, and craft detailed monsters out of crumpled paper. “He has a really big heart, so that scares me a little,” Arleen told me. She worries that without the same tough exterior that her brothers developed, he’ll be hurt.

Marianna’s youngest, whom the family calls Gordo, is named Christian, in honor of his late uncle—a decision Marianna made in the hospital bed after a scary, complicated labor. “When I held him, I could just see so much of my brother in him,” she told me. Though Gordo bears his name, it’s Dan, Marianna’s eldest, who resembles Christian most strikingly. The ten-year-old has the same dark complexion and wiry build, and he moves with a restless energy that evokes images of the uncle he never met darting through the terraced maze of apartments on that East Austin hillside. Yet, like his cousin Diomani, he carries himself differently than the children who grew up at Booker T. One day recently, Dan was hit by a kid at school. Arleen and Marianna were shocked to learn that he didn’t hit back. “If somebody would’ve done that to us, we would’ve probably, like, got into a fight,” Arleen said. “They don’t know that life, and I think that is one thing I’m happy about.”

Maricela Juarez

Any story about absent fathers is also a story about mothers, and Maricela is the matriarch and heroine of this one. When I asked her recently what her life was like back when I first met her, she described the hopelessness of watching Christian follow in his father’s and elder brothers’ footsteps. “No matter what program they put him in, he continued to have this obsession for breaking into houses,” she told me. “It made me feel as a failure as a mom—that I had failed, and I didn’t know how to help him.”

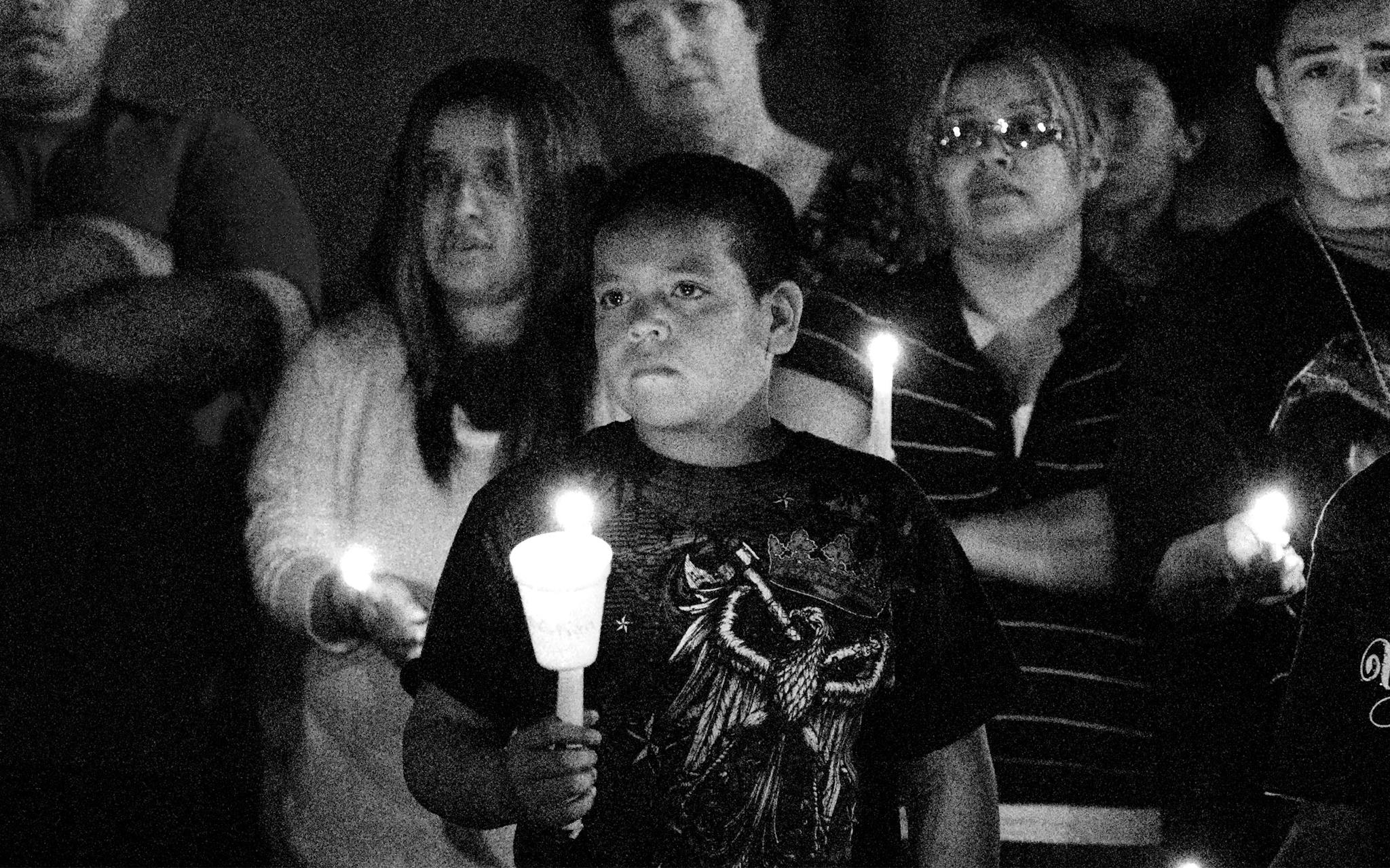

The days after Christian’s death had brought the familiar mourning rituals of the 0-2: the candlelight vigil, the taco-plate benefit, the red and black T-shirts airbrushed with Christian’s face, the balloon release on his birthday. But for Maricela, the questions lingered for years as grief turned to anger, and anger to blame. “I was blaming everybody that I could blame, including myself at times,” she told me. “So I prayed a lot and asked God to help me forgive . . . It’s taken all these years to be able to forgive and realize that losing Christian had a purpose.”

That purpose began to crystallize a few months after Christian died, when Maricela and I had the opportunity to share the Boys of Booker T documentary with a group of kids in a recidivism reduction program in San Antonio, where I lived at the time. We made regular trips to the facility, and after I moved to Dallas a few months later, Maricela continued to visit monthly for the next nine years, until COVID-19 ended the program. “Seeing how those boys, how it makes a difference in their lives, I can definitely see that God had a purpose in selecting Christian, and, you know, that has brought peace to me,” she said.

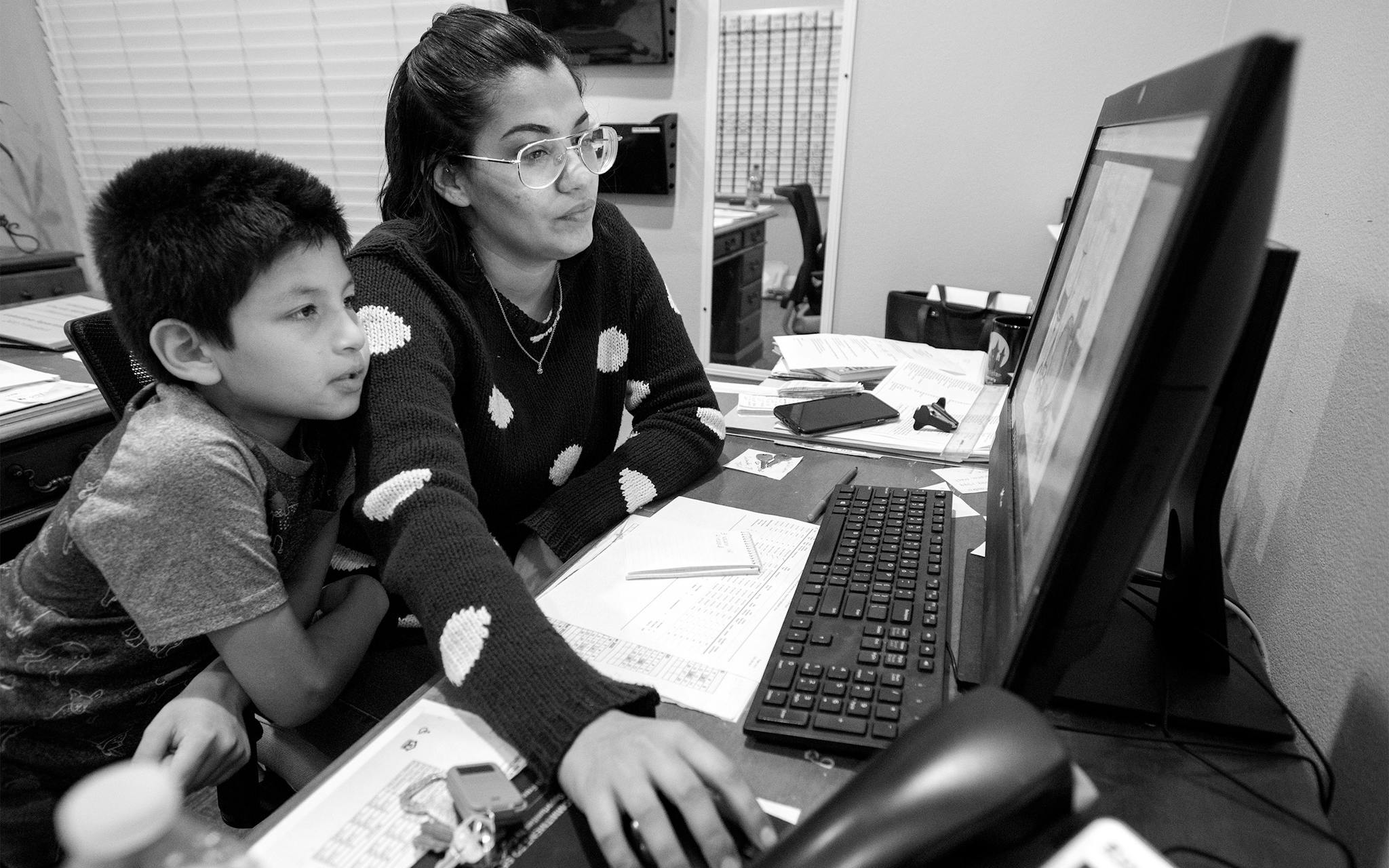

Inspired by that volunteer work, and with more flexibility after her youngest daughter started high school, Maricela began to hesitantly think about a life beyond Capt. Benny’s and the survival mode in which she’d lived for more than two decades. She enrolled in high school equivalency classes at Austin Community College and, after completing that program in 2016, began coursework in criminal justice. In 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, she earned her associate’s degree working from her kitchen table. “I felt that if I could be in the criminal justice system, that I could make a difference because those kids and I, we can relate. I feel that I could have the compassion to work with them and guide them, which is something that I always longed for when Christian was involved in the juvenile system.”

At Maricela’s home, the quiet nights are disturbed only by cicadas, barking dogs, and the sound of motorcycles revving up and down I-35. Her plans to work in the criminal justice system have been postponed by the pandemic, and today she works as an enrollment specialist for ACC’s adult education division at the school’s Eastview Campus—just across the street from Booker T. “Some days it’s harder than others,” she said, to drive through the old neighborhood on her morning commute. Although she isn’t working professionally in criminal justice, she recently began sharing her story again in a victim impact class required for young offenders in the Williamson County juvenile system.

Her face has aged, and the involuntary twitch of her left eye evinces the years of trauma she has endured. But her smile and explosive laugh haven’t faded, and her faith in God and hope for the future remain undiminished. While it’s impossible to know where Maricela would be today if Christian were still alive, it’s clear that his death served as a catalyst. “It had a big impact on my life, and it caused a positive change,” she said. “He loved me so much . . . He never wanted to cause pain to me, so I try not to get sad. And that’s why I wanted to turn losing Christian into something positive.”

Jeffrey McWhorter is a photojournalist and videographer who lives in Dallas.

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Boy From Booker T.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Austin