This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Mexican Revolution’s most famous photograph was taken in Mexico City on December 6, 1914. Wearing polished riding boots and a formal uniform, Pancho Villa sits crookedly in the ornate presidential chair. To his left is the thin, cold-eyed Morelian horse trainer, Emiliano Zapata. Two dozen revolutionaries crowd into the photograph. Over Zapata’s left shoulder is a boy with prominent ears and an avid grin. Leo Reynosa was a fifteen-year-old in Villa’s army. He had joined the federal army, hoping to fight the American forces that occupied Veracruz, but instead was sent against Villa’s guerrillas, who captured him, won his allegiance, and made him a captain at sixteen because he could read. Like other survivors of the revolution, Reynosa eventually came to Texas in search of work. For the past 47 years, he has owned Leo’s Mexican Restaurant in Houston. A framed copy of the photograph greets his clientele.

The Mexican Revolution seems such a bygone moment in history that it is startling to realize that some of the people who passed through its chaos are still alive—that the old man sitting on a folding chair in the corner of a restaurant or an ice house was once a bandolier-clad soldado. On November 20, Reynosa and four other Texas veterans of the Mexican Revolution will be honored at a Texas City reunion organized by Manuel Urbina II, a historian at the College of the Mainland. Urbina has found eleven of those old soldiers. Now in their eighties and nineties, they live in the Southwest United States. They fought for every major faction except the side that won.

Jesús González, a retired machinist in Baytown, rode with Villa and Zapata. At the age of nine, he handled horses for Zapata’s guerrillas. Recommended to Villa by Zapata, González became Villa’s teenage confidant and spy. He inspected enemy towns in the guise of an orange salesman. In 1916 he was shot three times while attacking a machine gunner with a horse and lariat. Villa discharged González in his hospital bed and gave him a pistol with a personal inscription. The other Texas survivors pictured on these pages—Ausencio R. Arias, Rafael Lorenzana, and Miguel Contreras—had less contact with those romantic icons Zapata and Villa.

It was not unusual for a veteran of the revolution to come to Texas. Though the ultimate winners came from Sonora, a state south of Arizona, the civil war could not have been fought in such savage and prolonged fashion without Texas. The peasant armies came here to buy beef, horses, and guns. Revolutionaries plotted in San Antonio and El Paso. They raided villages and ranches in the Valley, and by 1916, 50,000 U.S. troops guarded the Lower Rio Grande. Seven decades later, our proximity to the war continues to distort our outlook. Our understanding of the Mexican Revolution places too much emphasis on the mythological generals, Villa and Zapata, and not enough on the causes and eventual victors.

On the eve of the 1910 revolution, Mexico was a land of prolific natural resources. The lead, copper, coal, and zinc mines were booming, and Mexico produced one sixth of the world’s oil. But the resources were untaxed, and most of the profits were going to American and British companies. Three percent of the Mexican people controlled the national wealth.

At eighty President Porfirio Díaz was a classic Latin American dictator. He came to power as a liberal and had hung on with skill and firing squads for 34 years. Díaz kept the army large but weak, which discouraged coups. He enforced his will with a brutal state police known as the rurales.

In Morelos, a state south of the capital, Zapata initiated the armed revolt by seizing cornfields and turning them over to the peasants. Setting fires that could be seen from Mexico City, Zapata’s guerrillas preoccupied the Díaz regime, but the zapatistas didn’t get beyond Morelos.

Díaz’s nemesis was Francisco Madero, a charismatic orator and political writer who offered himself as an opposition candidate in 1910. Díaz jailed the upstart, but Madero escaped to Texas and from San Antonio called for a rebellion against Díaz. He gained an ally in Venustiano Carranza, a former governor of Coahuila, but the maderistas’ revolt flowered first in the neighboring state of Chihuahua.

In May 1911 thousands of El Pasoans watched the maderistas storm the federal garrison in Juárez, Chihuahua. Mestizos in sombreros blared a din of bugles; Yaqui Indian fighters wore loincloths. One band of Chihuahuan rebels was commanded by Francisco “Pancho” Villa, a sometime cattle rustler and butcher-shop owner. Two days after Juárez fell, Zapata overran the federal army at Cuautla in Morelos, and the Díaz regime collapsed. Díaz sailed to exile in Prance.

The revolution was over; what followed was a bloody and treacherous civil war. The goals of the revolution were forgotten as factions struggled for power. Madero, who came from a wealthy clan in Coahuila, balked at the radical notion of land redistribution; he simply wanted an abolition of presidents-for-life. He tried to appease Zapata, but before he could assume the presidency in November 1911, the interim government sent a Díaz general, Victoriano Huerta, against Zapata.

Madero sealed his own demise by trusting Huerta. In February 1913 Huerta used disorder in the capital to stage a coup. When Madero’s brother was killed by a mob, he resigned. Three days later he ran afoul of the fugitive law and was shot in the back while “trying to escape.”

Though contemptuous of Madero, U.S. politicians were appalled by Huerta, who conducted affairs of state in a bar. Woodrow Wilson tried to humiliate Huerta out of office by landing U.S. forces at Veracruz, but that only fired anti-American sentiment. More effectively, Wilson opened the U.S.-Mexico border to arms transactions with the rebels. Meanwhile in Coahuila, Carranza had designated himself Jefe Primero, First Chief. In Sonora a garbanzo farmer, Alvaro Obregón, was commanding an able army of Yaquis and vaqueros. But Villa’s Dorados—the golden ones—were the ones who brought down Huerta.

Wilson favored Villa as Mexico’s eventual president because he seemed flexible and did not drink or gamble. On the other hand, he was a frequent rapist, as boy spy Leo Reynosa observed. But Villa was a brilliant military commander. He enlisted an expert artillery general, and with a combination of long cavalry sweeps and confiscated trains, he made his army incredibly mobile. With a keen sense for public relations, Villa reserved cars for American reporters and even a film crew as he swept toward Mexico City. Huerta tried to stop Villa at a natural fortress called Zacatecas, in the mountains north of the capital, but the rebels went straight up a silver-ore cliff, a high eagle’s nest. Huerta fled the country.

Carranza, a landowner like Madero, was the leading moderate. He cut off Villa’s coal supply to keep his trains from reaching the capital first, and Obregón, the Sonoran, took Mexico City in August 1914. But a constitutional convention collapsed when delegates approved Zapata’s plan to confiscate the haciendas, and Zapata and Villa, the radicals, chased Carranza and Obregón, the centrists, out of town. It was then that the two generals posed for their famous picture.

Carranza set up his headquarters at Veracruz and pressed for U.S. recognition with a combination of diplomatic concessions and raids in the Rio Grande Valley. Still Wilson’s favorite, Villa let a minor firefight in the state of Guanajuato put him out of the running. At Celaya in April 1915 Villa should have waited and bombarded Obregón’s outnumbered troops with artillery. Instead he ordered waves of soldados into a massacre. Obregón lost half of his right arm to a grenade in a subsequent skirmish, but Villa’s obsession cost him Wilson’s support.

Wilson recognized the Carranza regime in October 1915. He imposed an arms embargo against all other factions and allowed Carranza to move Mexican troops through U.S. territory, contributing to another defeat for Villa. In March 1916 Villa led a raid that killed eight American soldiers at Columbus, New Mexico. Wilson sent General John “Black Jack” Pershing across the border. Pershing’s troops could not catch Villa and took the worst of it in a scrape with carrancistas.

The 1917 triumph of the centrists evolved into the PRI, the Party of Institutional Revolution, a coalition so broadly constructed that it has ruled Mexico ever since. But the bloodshed had not yet run its course. Zapata still menaced the capital from the south. In 1919 in a deception condoned by his general, a colonel in Carranza’s army sent word to Zapata that he wished to defect; as an act of faith he killed 59 government soldiers. Coming to meet with the colonel, Zapata rode into the sights of six hundred guns.

As for Carranza, he might have died in esteemed retirement had he not tried to block the election of Obregón. Assisted by those who had supported Zapata, Obregón drove Carranza out of Mexico City in May 1920. Carranza sacked the federal treasury before fleeing on a train to Veracruz, but he was intercepted and driven into the mountains. The Jefe Primero was shot while sleeping on the mud floor of a peasant’s hut.

As Mexico’s president from 1920 to 1924, Obregón stabilized the country. His treasury secretary bought off Villa with a pension and ranchland. But none of the revolutionary leaders would know the satisfaction of old age. In July 1923 Villa was riddled with bullets by gunmen whose grudges were said to be personal, not political.

Obregón remained a powerful figure during the term of his successor, Plutarco Elías Calles. The 1917 constitution, which limited presidents to one term, was amended to allow Obregón to return to office. In July 1928, ten days before Obregón was to be inaugurated, he attended a banquet of revolutionary heroes, where an assassin posing as a caricaturist shot him dead.

A memorial has been built on the site of the assassination. Inside the art decolike pyramid, a glass jar contains the talisman that inspired the constitutionalists after the turning-point battle of Celaya. Pale and floating, it is the pickled remains of Obregón’s strong right arm.

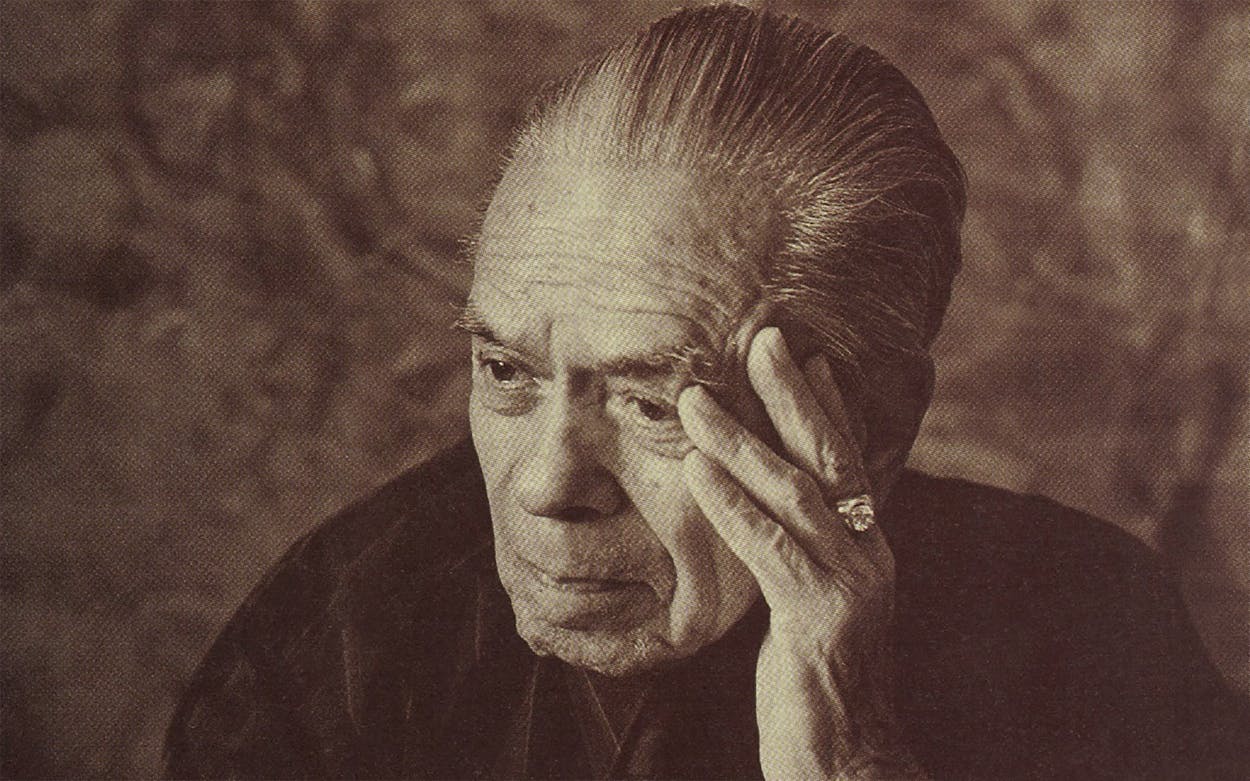

Leo Reynosa

Houston

Houston’s restaurateur Leo Reynosa, 89, has never been shy about his Pancho Villa days. The walls of Leo’s Mexican Restaurant, which opened at its present location on South Shepherd in 1941, are lined with images of the revolution. When American troops occupied Veracruz, Reynosa, then 15, persuaded relatives to sign papers allowing him to defend his country. Instead, he was marched off to battle guerrillas. When he was captured by Villa’s troops shortly after, Reynosa chose defection over death. He became a bookkeeper for Villa and was close enough to observe that Villa “used to get married every few minutes.” In 1918 Reynosa left the Mexican battlegrounds for Texas.

Jesús González

Baytown

Jesús González, now 86, was 9 when the revolution swept him away from his home in Querétaro to serve Emiliano Zapata’s troops. By 1913 he was a daring boy spy for Pancho Villa, studying between missions with the camp’s teacher. González says that despite his youth, Villa confided in him and kept him out of photographs for fear of exposing a good spy. González left the fighting after he was wounded three times in the chest, near his heart, and moved to Texas in the early twenties, eventually settling in Baytown. Although González has stayed in touch with relatives who live near San Luis Potosí, he says he is no longer interested in Mexican politics.

Rafael Lorenzana

Mercedes

Rafael Lorenzana entered the fighting at the age of 13 on the side of Venustiano Carranza. In 1915 he was captured by Villa’s troops and heard the general order his execution. Offered the chance to join up instead, Lorenzana agreed, although he planned to cross over again to Carranza. But the villistas took him for a brave man and promoted him to sergeant. Gradually persuaded that Villa was the better leader—Villa didn’t allow looting—Lorenzana became a major at 19. With memories of the bodies he was ordered to pile and burn, Lorenzana left Mexico in 1920 and moved to Mercedes, where he became a farmer. Lorenzana, now 89, watched the recent Mexican elections with disgust.

Miguel Contreras

Baytown

As Miguel Contreras crossed into Texas in 1919, he threw his rifle into the Rio Grande. “I came to work, not fight,” he says. Contreras had soldiered with Venustiano Carranza’s forces for six years. Originally drawn into the military by hunger—soldiers had food, civilians often didn’t—he had had enough of the bloodshed and headed for booming Baytown. The Humble refinery was going up, and Contreras found work as a mule driver, hauling supplies around the site. In all, Contreras was employed by Exxon, Humble’s successor, for 37 years at various jobs, the last years as a cement finisher. Now 87, he is more interested in American politics than in Mexican politics.

Ausencio R. Arias

Houston

Ausencio R. Arias joined Venustiano Carranza’s forces in 1916 out of moral outrage. He and his father, who worked as peddlers in San Luis Potosí, had a run-in with federal soldiers who roughed them up and stole their merchandise. When Arias protested, the two men were locked up for nine days. Leaving home without revealing his plans, Arias joined the carrancistas to fight injustice. After three years, a leg wound gave him a chance to reconsider his options. He decided to move to Houston, where a brother had found work. Now 93, Arias shoveled coal for the railroads, helped build a Port Arthur refinery, and learned the welding trade before retiring at the age of 80.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads

- Mercedes

- Houston