This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

My earliest memory of tortillas is my mamá telling me not to play with them. I had bitten eyeholes in one and was wearing it as a mask at the dinner table.

As a child, I also used tortillas as hand warmers on cold days, and my family claims that I owe my career as an artist to my early experiments with tortillas. According to them, my clowning around helped me develop a strong artistic foundation. I’m not so sure, though. Sometimes I wore a tortilla on my head, like a yarmulke, and yet I never had any great urge to convert from Catholicism to Judaism. But who knows? They may be right.

For Mexicans over the centuries, the tortilla has served as the spoon and the fork, the plate and the napkin. Tortillas originated before the Mayan civilization, perhaps predating Europe’s wheat bread. According to Mayan mythology, the great god Quetzalcoatl, realizing that the red ants knew the secret of using maíz (maize) as food, transformed himself into a black ant, infiltrated the colony of red ants, and absconded with a grain of corn. (Is it any wonder that to this day, black ants and red ants do not get along?) Quetzalcoatl then put maize on the lips of the first man and woman, Oxomoco and Cipactonal, so that they would become strong. Maize festivals are still celebrated by many Indian cultures of the Americas.

“A woman was cooking her husband a tortilla one morning when the image of Christ appeared on it. Before they knew what was happening, his breakfast became a local shrine.”

When I was growing up in El Paso, tortillas were part of my daily life. I used to visit a tortilla factory in an ancient adobe building near the open mercado in Ciudad Juárez. As I approached, I could hear the rhythmic slapping of the masa (dough) as the skilled vendors outside the factory formed it into balls and patted them into perfectly round corn cakes between the palms of their hands. The wonderful aroma and the speed with which the women counted so many dozens of tortillas out of warm wicker baskets still linger in my mind. Watching them at work convinced me that the most handsome and deliciosas tortillas are handmade. Although machines are faster, they can never adequately replace generation-to-generation experience. There’s no place in the factory assembly line for the tender slaps that give each tortilla character. The best thing that can be said about mass-producing tortillas is that it makes it possible for many people to enjoy them.

In the mercado where my mother shopped, we frequently bought taquitos de nopalitos (small tacos filled with diced cactus, onions, tomatoes, and jalapeños). Our friend Don Toribio showed us how to make delicious, crunchy taquitos with dried, salted pumpkin seeds. When you had no money for the filling, a poor man’s taco could be made by placing a warm tortilla on the left palm, applying a sprinkle of salt, then rolling the tortilla up quickly with the fingertips of the right hand. My own kids put peanut butter and jelly on tortillas, which I think is truly bicultural. And speaking of fast foods for kids, nothing beats a quesadilla, a tortilla grilled-cheese sandwich.

Depending on what you intend to use them for, tortillas may be made in various ways. Even a run-of-the-mill tortilla is more than a flat corn cake. A skillfully cooked homemade tortilla has a bottom and a top; the top skin forms a pocket in which you put the filling that turns your tortilla into a taco. Paper-thin tortillas are used specifically for flautas, a type of taco that is filled, rolled, and then fried crisp. The name flauta means “flute,” and probably refers to the Mayan bamboo flute, but the only sound that comes from an edible flauta is a delicious crunch that is music to your palate. In Mexico flautas are sometimes made as long as two feet and then cut into manageable segments. The opposite of flautas is gorditas, meaning “little fat ones.” These are very thick small tortillas.

The versatility of tortillas and corn does not end here. Besides being tasty and nourishing, they have spiritual and artistic qualities as well. The Tarahumara Indians of Chihuahua, for example, concocted a corn-based beer called tesgüino, which their descendants still make today. And everyone has read about the woman in New Mexico who was cooking her husband a tortilla one morning when the image of Jesus Christ miraculously appeared on it. Before they knew what was happening, the man’s breakfast had become a local shrine. Then there is tortilla art. Various Mexican artists throughout the Southwest have, when short of materials or just in a whimsical mood, used a dry tortilla as a small, round canvas. And a few years back, at the height of the Chicano movement, a priest in Arizona got in trouble with the Church after he was discovered celebrating mass using a tortilla as the host. All of which only goes to show that while the tortilla may be a lowly corn cake, when the necessity arises it can reach unexpected distinction.

Pressing Issues

There are many kinds of corn—many colors and many sizes, ranging from those tiny, cute canned ears of corn to the Texas-size twelve-inchers. The most common type for making tortillas is white corn, with a big, meaty kernel, but your choice of colors does not stop here. Blue tortillas are one of the Southwest’s finest products. Made from Indian blue corn (a natural variety), these tortillas have a deep slate-blue cast. There is also red and even black corn. I have always felt that red, white, and blue tortillas would be a great Fourth of July food, but I fear that the Daughters of the American Revolution would frown on the idea.

“After dinner, instead of asking the waiter for a doggie bag, I asked for an extra tortilla to carry the leftovers home in. Later that night I had a fantastic burrito for a snack.”

Like everything else, there are good, bad, and indifferent tortillas. A connoisseur can smell the quality of superior tortillas, and the only way to become a connoisseur is to learn the ins and outs of making them yourself.

You begin your lesson by buying the fresh prepared masa from a tortilla factory. If you live anywhere in the Southwest there is one close to you. Just look in the Yellow Pages. The only time when it’s hard to get masa is around Christmas, when everyone is making tamales for Noche Buena (Christmas Eve) and Noche Vieja (New Year’s Eve). But even so, it’s not a bad idea to call first, because tortillas are made early in the morning and delivered throughout the day, and the factory might run short of masa. You can also use Quaker instant masa harina, which is carried by most supermarkets. The instructions are on the package. But don’t try to use cornmeal; it will not do at all.

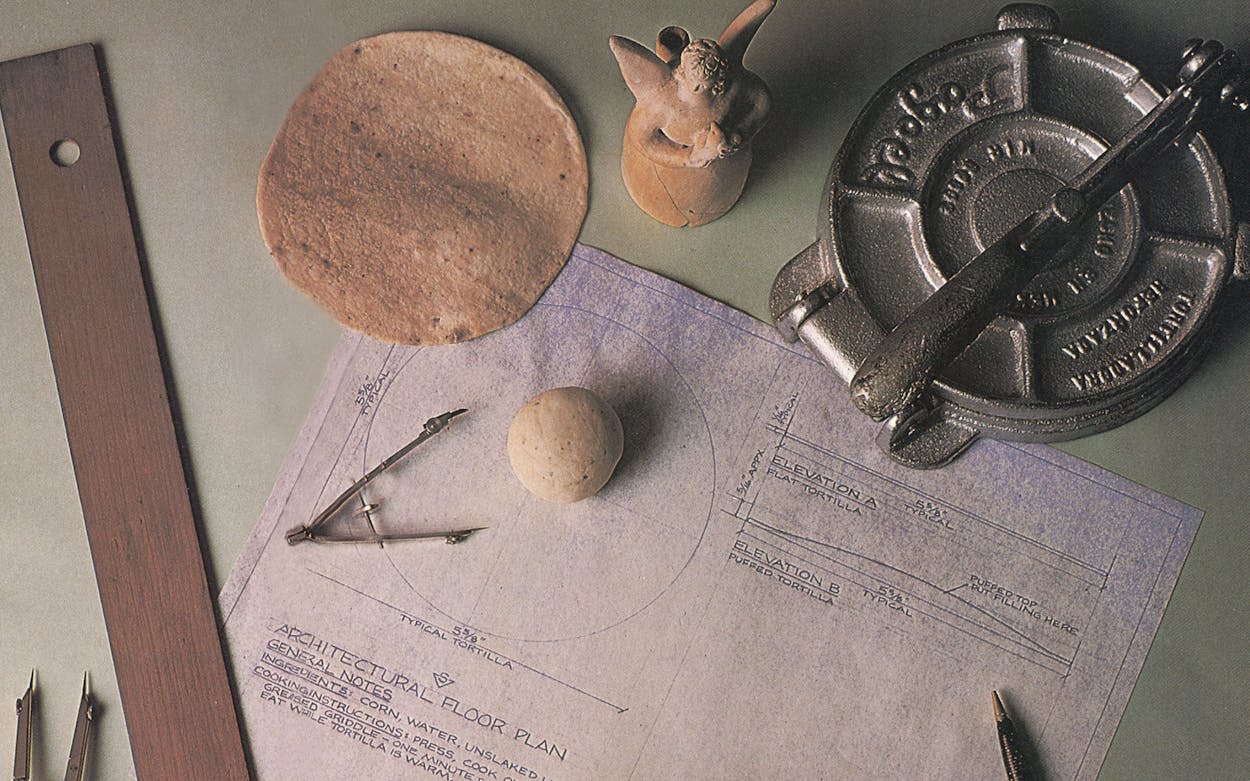

Now, let’s say you have run out to your local barrio tortilla factory and bought one and a half pounds of prepared masa. While you were in the store you noticed several objects that looked like small printing presses. You asked what they were and the man told you they were tortilla presses. You blushed at your ignorance and decided you’d better get one. And it is best, unless you plan to slap the masa from one hand to the other till you get a perfectly round tortilla—which may very well be never. Take it from me, you are better off with a tortilla press, and the sturdier and heavier the better. They usually cost $7 to $10.

To be as authentic as possible you should also have a comal. What is a comal? A comal is a round, flat iron griddle that you put over the burner. They are hard to come by in the U.S., but fortunately you can get by without one. One or two big, heavy metal pans, lightly greased, will do nicely. An electric griddle will do in a pinch but sometimes does not give sufficient heat.

You are now almost ready to make the first of many tortillas in your lifetime. The last things you need are two pieces of waxed paper or, better, two pieces of polyethylene from a sandwich bag. (Ideally, the plastic should be from a Bimbo Mexican brand bread wrapper.) Put one of these pieces on the bottom plate of the press, roll a ball of masa one to two inches in diameter, and set it down lightly on the plastic. Put the second piece of plastic on top of the dough ball and squeeze the top of the press down very firmly. Open it and peel off the top piece of plastic, then place the tortilla in your hand and peel off the other piece of plastic. (The order is important. If you try to peel the tortilla off the plastic I guarantee you will make a big mess and have to start over.) Before you cook your creation, take one last look at it. Is it too gorda (fat)? You didn’t press hard enough. Is it too grainy or too seca (dry)? Well, amigo, you can still put a little more water in the dough, but don’t add too much or you will have another fine mess and the plastic will never come off your tortilla. When you’re sure all is going well, carefully lay the tortilla on a hot pan or griddle over medium heat. Some people like to slam them down and watch air bubbles form in the dough, but that results in a tortilla with a somewhat cratered surface.

You are anxiously watching your first tortilla cook on the griddle. When you see that the edges have begun to dry, flip it over; if you let the edges dry out completely, they will be hard. How do you flip it? Unless you have quick, experienced fingers, you’d better use a spatula. After cooking the tortilla on the second side, flip it back to the first side. If the masa and the heat are just right, the tortilla will now puff up. The side that puffs up is the right side, the thin top skin; this forms the pocket where the fillings go when you make tacos.

When your tortilla is done, pick it up from the griddle and place it between the folds of a thick kitchen towel or in a wicker tortilla basket with a sombrero top (which you get at an import store). These baskets insulate very effectively. Just put a cloth napkin inside to absorb condensation. Continue pressing and cooking one tortilla at a time until the basket is full. Don’t press all the tortillas at once, or they will dry out.

Now, all this may seem a little trying the first time around, but before you know it, making tortillas will become second nature. You can easily reheat them by wrapping them in foil and setting them in a 300-degree oven (or toaster oven) for five minutes. And one of the best and highest uses of the microwave oven is reheating tortillas; you can do a dozen in less than three minutes, and they will stay moist. Another method we sometimes use at home is to heat a pan and use it like a comal. But by far the best way to warm a tortilla is to lay it directly over the flames of a gas burner for a few seconds. I have amazed many a gringo friend by sticking my fingers into the fire to flip a tortilla. An electric burner will work too, but you’ll have to experiment to find the right setting. If the heat is too intense, in one second your tortilla will burn and taste awful. There are many ways to reheat tortillas, and it doesn’t matter which one you use as long as you don’t let them go to waste.

Flour Power

The flour tortilla, comadre to the corn tortilla, has a much shorter history. The flour tortilla originated in the state of Sonora, the breadbasket of Mexico. Like its maize counterpart, the flour tortilla (tortilla de harina) has many aspects, sizes, and styles. It is common in northern Mexico and in the southwestern United States but not at all well known around Mexico City.

In South Texas flour tortillas are small and thick. In West Texas they are medium-sized. In California it’s a mixture, though big, thin types predominate. In Sonora and adjacent Arizona, tortillas de harina are large—eighteen inches in diameter. There they are folded and put next to your plate, like napkins. The last time I was in Phoenix, instead of asking for a doggie bag I asked for an extra tortilla to carry the leftovers in. Later that night I had a fantastic burrito for a snack. When a burrito is fried and served with guacamole and salsa on top it becomes a chimichanga.

Flour tortillas spoil faster than corn tortillas, though they do make wonderful sandwiches, even at classroom temperature. I remember going to school with a burrito de chorizo con huevos (Mexican sausage and eggs) staining my brown lunch bag and khaki pants. Across the school yard sat my friend Suzy with her Roy Rogers lunch box, spilling peanut butter and jelly from her white-bread sandwich onto her freshly pressed dress. For kids, cultural differences are sometimes not so large after all.

To make two dozen flour tortillas you need 1 pound of sifted white flour, 2 teaspoons of salt, ¼ cup of lard, and 1 cup of warm water. Place the flour in a bowl and cut in the lard as if you were making piecrust. Dissolve the salt in the water, add that mixture to the flour and lard to make a pliable dough, and knead it until it is soft and elastic. Grease your hands and form dough balls 1½ inches in diameter or slightly bigger. On a floured board, use a rolling pin to roll out each dough ball to at least 8 inches in diameter. (You can’t use a tortilla press because of the elasticity of the dough.) Cook the tortillas on an iron griddle over medium heat, as you would corn tortillas.

With this same recipe my mamá would sometimes make sopaipillas. First she would roll 1¼-inch balls of dough very thin, slice them pizza style into four pieces, and then fry the wedges. After draining these puffy delicacies she would roll them in sugar and cinnamon or pour honey on them. (You can also make whole wheat tortillas, but don’t try to fry these for sopaipillas; the dough is too coarse.)

Once you know the beauties of both corn and flour tortillas, you may have trouble deciding which you prefer. Your choice will depend partly on tradition (some recipes call for a particular type) and partly on your mood. If you are a health food addict you will be pleased to hear that the corn tortilla has no salt, saturated fats, or preservatives. Weight watchers should know that depending on size, the average corn tortilla has from 35 to 50 calories, while a flour tortilla has 23 to 65 calories, depending again on size and how much lard is used. (Store-bought tortillas tend to have less lard.) By comparison, a half-inch slice of white bread has 70 calories. As you can see, you are better off with a tortilla.

Consuming Passions

When I was in the service and the only tortillas I could get were Ashley’s canned brand, from El Paso, my mother took pity on me and mailed fresh ones special delivery. (That was twenty years ago, when special delivery was actually special and delivered.) I appreciated the homemade tortillas so much that she offered to get me my great-aunt’s recipe for tortilla cookies, but I waited too long to follow up. Tía Nina died last year at the age of 94, taking the recipe with her. I can’t share the tortilla cookie recipe, but I can do the next best thing and pass along some other family favorites.

Tostadas

In Mexican homes it is the custom to save all the day-old tortillas and pan-fry them. Presto! Tostadas (tostaditas, if they’re small). That is why there is always a bowl of tortilla chips and hot sauce in Mexican restaurants. (Of course, this is not to say that they are made from yesterday’s tortillas.)

Tortilla Soup

My mother’s favorite way of using stale tortillas is in tortilla soup. First she makes chicken or beef broth with tomatoes and spices for flavor. She always adds a dash of cominos (cumin), which makes the difference with a lot of Mexican soups. The tortillas are diced, fried, drained, and added to the bowls of soup at the last moment so the chips won’t get soggy.

Albóndigas

Another great recipe for leftover tortillas is albóndigas—Mexican matzo balls. Say you have a dozen stale tortillas. You grind them with a mortar and pestle or in a food processor, or for more authenticity, use a metate (a Mexican mortar made from rough volcanic stone). Then you add 1 egg, ¼ teaspoon of salt, ½ cup of grated white cheese (such as farmer’s cheese), and ½ cup of hot milk and stir. Refrigerate the dough for an afternoon or overnight to allow the tortilla particles to soften. Later that day or the next morning knead the dough well and add more milk if necessary. From this dough make a dozen small balls, the albóndigas. In a frying pan heat lard (shortening will do, but lard is more authentic) and fry the albóndigas until they are golden brown. Drain well and they are ready to be added to soup; chopped cilantro (coriander) makes an attractive topping.

Other Recipes

Diana Kennedy’s The Tortilla Book (Harper & Row) gives directions for a multitude of main dishes using tortillas.

Hot Off the Presses

Couldn’t make a tortilla if your life depended on it? Relax—help is at hand.

The automatic salter at El Galindo tortilla factory is not working right today, so Mary Riojas is salting nacho chips. Shaker in hand, she stands by the conveyor belt, lightly sprinkling the chips as they emerge from a deep-fat fryer the size of a Volkswagen. Mary is one of the few human beings involved in a highly automated process that turns out—every day—17,000 dozen corn tortillas, 7000 ten-ounce packages of chips, 4000 boxes of taco shells, and 13,000 dozen white flour and whole wheat flour tortillas.

Out of one large and two small buildings in the Mexican American section of East Austin, El Galindo supplies tortillas to grocery stores, restaurants, and schools in Austin, Dallas, Houston, and East Texas. It even has a small share of the market in San Antonio, the acknowledged tortilla capital of Texas.

To step inside a tortilla factory is to be totally immersed in the smell of corn. Hours after you leave, the aroma clings to your clothes and fills your nostrils. Whatever you eat for lunch or dinner that day tastes faintly like a tortilla. Small wonder. Throughout the day at El Galindo’s soft tortilla division, corn is constantly being transferred from the 40,000-pound storage tank to cooking vats that look like small coal cars. There the kernels are simmered for thirty to sixty minutes with water and cooking-grade crushed lime. (The lime, a traditional additive probably since Mayan times, reacts with the corn to give the masa the proper consistency, speed up the cooking process, and increase shelf life. Tortillas that will be refrigerated or used right away have less lime and therefore a more delicate taste.)

After cooling for twelve to eighteen hours, the corn mixture is ground to masa in a stone grinder. Machines then efficiently feed the masa into a hopper from which it is forced between two rollers. As the sheets of dough emerge, they are neatly sliced into rounds by revolving die cutters. A conveyor belt trundles the disks through a gas oven for forty to seventy seconds and drops the cooked tortillas onto a chain conveyor that shuttles them back and forth until they cool. At the end of the line, five women count, sack, and box a dozen or more tortillas at a time.

When it’s lunchtime at the plant, the conveyor belts are still. The workers, in their aprons and hairnets, open the lunches they have brought. A question occurs to the casual onlooker: would anyone who works in a tortilla factory voluntarily eat a tortilla—ever? The answer is clear. In the middle of the table are two fresh packages of the specialty of the house.

—Patricia Sharpe

- More About:

- Tacos

- Recipes

- TM Classics

- Mexican Food

- Longreads

- El Paso

- Austin