This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Isaac Tigrett sat in his Stoneleigh Hotel penthouse in Dallas—surrounded by Judy Garland’s bowler hat, Pat Boone’s white bucks, scores of famous guitars, hundreds of gold records, and approximately three fourths of every inanimate object that the Beatles ever touched—getting hot under his high British collar about the two Hard Rock Cafes in Texas. “The people of Houston are about to be cheated, as have the people of Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco,” he said, referring to Hard Rocks owned by his ex-partner, Peter Morton, who happens to own the new Hard Rock in Houston too. But Tigrett, who recently opened the Dallas Hard Rock Cafe, didn’t go so far as to suggest that the state wasn’t big enough for the both of them. Competition hurts only the weak, he intimated. “Maybe it will finally get through to this guy that you can’t just play around with a famous name and try to make money off of it,” Tigrett said. “He is totally cash-oriented.”

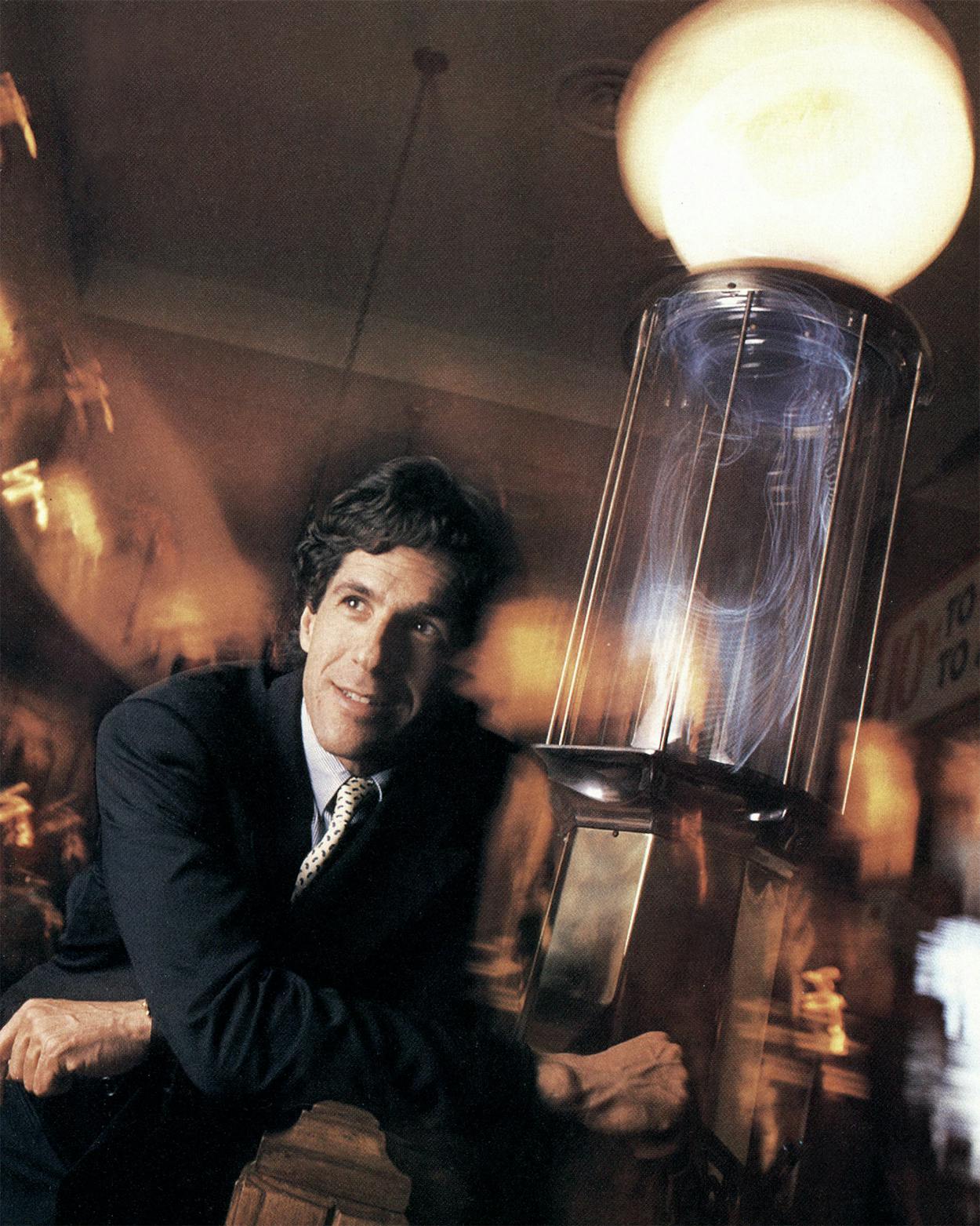

Peter Morton is not spoiling for a fight. The son of a Chicago restaurateur, Morton, 37, was the bottom-line brains of the original Hard Rock operation. With his deeply tanned, handsome features and pressed blue jeans, Morton appears to be the essence of Southern California capitalism. “I’m just going about my own business, opening up restaurants,” he explained. “I’ve been doing what my family’s been doing for seventy-five years and will continue to do for a long time.”

The grand openings of the Hard Rocks in Houston and Dallas last November constituted nothing less than a showdown between Tigrett and Morton, who together opened the first Hard Rock Cafe in London in 1971. The Hard Rock has gone on to become the most-successful restaurant marketing story since McDonald’s. But now the two owners are bitter rivals who retain rights to the Hard Rock name and concept, roughly splitting the world in half as to where new locations can be established. The line of demarcation between their territories in Texas lies somewhere on Interstate 45 between Dallas and Houston.

Before the Hard Rocks arrived in Texas, you probably read gossip items in which celebrities and the Hard Rock Cafe were mentioned in the same sentence. Or maybe you’ve seen one of the ubiquitous Hard Rock Cafe T-shirts, emblazoned with the earth-toned company logo, worn by millions of young people as a status symbol. A noisy, boisterous bar and restaurant for hipsters of all ages and families—especially families—Hard Rocks are hardly unique. They are essentially yuppie theme restaurants that feature classic American diner fare, like burgers and ribs, with rock and roll decor—guitars, gold records, and other artifacts—hanging on the walls. Loud, loud music blasts out over the house sound system. What separates the Hard Rocks from the rest of the pack, however, is their knack for attracting the rich and famous, particularly in New York, Los Angeles, and London—a knack that supplies the Hard Rocks with a steady stream of customers eager for a glimpse at someone from the pages of Rolling Stone. Because there are only eight Hard Rock Cafes in the world so far, the places have a mystique that any other restaurant would kill for. The Dallas and Houston Hard Rocks may share in that mystique, but in terms of philosophy, they diverge drastically, each establishment reflecting the personality of its owner.

Isaac Burton Tigrett, 38, the son of a Memphis financier, is the wide-eyed, bearded guy behind the “Save the Planet” and “Love All, Serve All” slogans for which the Hard Rock Cafes are famous. His rock and roll memorabilia are an amassment of artifacts that bear witness to both his love for music and his collector’s mania (Tigrett refers to girlfriend Maureen Starkey, the former wife of Ringo Starr, as “my ultimate collectible”). Tigrett manages to mix sixties’ spirituality and modern marketing in a most intriguing way. His heroes are his guru, Sai Baba, whose likeness appears on a wall in the Dallas Hard Rock, and Trader Vic, the restaurateur who brought a slice of Polynesia to cities around the world in the forties and fifties. As Tigrett sees it, the Hard Rock is a way of saving people’s souls through rock and roll. He is a man with a mission, which at the moment that I met him was the debut of his Dallas Hard Rock Cafe. Still, he couldn’t ignore what was going on two hundred miles to the south, where Peter Morton was opening his Hard Rock three weeks ahead of Tigrett’s.

“He spends about one fifth the time, money, effort, and interest in Hard Rocks that I do,” Tigrett grumbled. “As far as I’m concerned, the image that he opens is a little shy of what it should be. It’s sad. I tried to influence him in every way, but that’s the difference in our characters. He’ll have a couple guitars and a couple gold records, but he’ll have satellites, old signs from shooting galleries, and he’ll have sort of the Friday’s-style eclectic bullshit that went out in 1969.”

Peter Morton is less interested in saving people’s souls than in serving them a good hamburger. He is basically a businessman. “Listen,” he said while overseeing last-minute details for his restaurant’s opening, “if we were poisoning people, you could have the greatest rock and roll memorabilia in the world and you’re not going to have any business. The Hard Rocks I own have great food and great service for the money.” As for the aura surrounding the restaurant, he shrugged: “Your guess is as good as mine.”

The confusing saga began in 1971, when Tigrett and Morton, two young Yankee expatriates in London, had money in their pockets and time on their hands. Morton had recently graduated from a hotel-and-catering school and was managing a small, successful American-style restaurant for his father. Tigrett, who had been selling Rolls-Royces and seeking higher truths, approached him with an idea for opening a loose, “classless” cafe in the middle of stuffy Mayfair that would satisfy their longing for an American hamburger, then a rare commodity in England. The two staked $50,000 on a cozy little bar and restaurant decorated with pop art, pennants, and banners and featuring rock music as the background accompaniment.

In a matter of months, the Hard Rock was quite the rage, attracting a clientele that included members of the British music industry, who adopted it as a hangout and brought recording stars and their artifacts with them. Paul McCartney, for instance, debuted his band, Wings, on the premises. The queues out front quickly became the most famous in Western Europe. Classless or not, those with money, status, or fame could skip the queue entirely, a privilege extended to card-carrying members of the Hard Rock Express Club. In 1975 the London Times named it England’s top family restaurant.

Life couldn’t have been sweeter. Except that as the restaurant’s popularity grew, the two partners grew further apart. “I didn’t realize that a degree from hotel-and-catering school doesn’t really qualify you for anything,” Tigrett said of Morton. “He was the educated guy, and I was the guy with the idea. It wasn’t long before I realized that I had a very different value system and different attitudes about life. We drifted apart almost immediately after the opening. Oddly enough, I became totally involved in the kitchen, and he became totally involved in the social aspect. He was always sitting at the bar, and that’s the way it went for several years.”

In 1979 their clashing styles led to a legal divorce that dragged on more than four years. They ultimately agreed to share the name and the marketing idea, Tigrett keeping London and opening branches in New York in 1984 and Stockholm in 1985 and claiming Iceland, Tokyo, and the United States east of the Mississippi River except Illinois. Morton moved stateside, opening Hard Rocks in Los Angeles in 1982, San Francisco in 1984, and Chicago in 1985. Hard Rocks for Honolulu, San Diego, and New Orleans are on Morton’s boards, and he has options in Israel, Argentina, Brazil, Australia, and the United States west of the Mississippi.

Both have done well with their ventures. Tigrett went public with his holding company in Britain in 1983. Its pretax profit for the first six months of 1986 was $1.3 million on sales of $9.6 million. Morton’s L.A. Hard Rock, a film-and-music-industry clubhouse, grosses more than $15 million annually. Tigrett’s New York Hard Rock rang up $7 million in sales its first year. As with any modern rock venture, T-shirt merchandising is a key income generator for both. Morton’s Hard Rocks have sold more than a million shirts. The New York Hard Rock averaged $165,000 a week in T-shirt sales last summer, or about 28 per cent of the gross, according to Tigrett. For all of their conflicting viewpoints, the two agree that the system works.

They also concur that Texas is a good place for Hard Rocks to be. Although he briefly contemplated opening in Washington, D.C., or Boston, Tigrett insists that Dallas was his only logical next choice. “I like the conservatism and at the same time the aggression in business and society,” he said. “It’s not as decadent as New York or L.A. It’s still family-oriented, still has high morals, and it is church-oriented.” Tigrett will spare no expense on his latest $8 million Hard Rock; he refurbished the Wrecking Bar antique shop on McKinney Avenue into what he calls the supreme court of rock and roll.

Morton’s Houston Hard Rock, on Kirby Drive, is a $2.5 million structure, built from the ground up, resembling a neo-Grecian branch bank. His Hollywood connections are evident by an impressive investor roster, which includes film producers Steven Spielberg and Peter Guber, Paramount Pictures chief Barry Diller, actor Henry Winkler, and singer Placido Domingo. Willie Nelson and John Denver also are Houston investors, but more for their name value than for their financial clout. “I put up most of the money myself,” Morton stated matter-of-factly. The Hard Rocks are not Morton’s be-all and end-all. An eatery bearing his last name is one of Los Angeles’ trendiest, and he’s developing another mass-market dining concept. Opening a Hard Rock in Houston, he explained, is simply good business: “It’s the fourth-largest city in the United States. It just seemed like a city of the future, with its relationship to the space industry, to oil, and I always had a special affinity for it.”

Both Hard Rocks opened with the sort of fanfare one expects of a movie premiere, a stadium dedication, or a similar event of great civic import—but not a restaurant. Morton came out of the gate first. Amid a swarm of searchlights, crowds lined police barricades along Kirby, stretch limos congregated around the entrance, and singer Kenny (“Footloose”) Loggins performed in a tent next door for a fundraiser, which netted $250,000 for the DePelchin Children’s Center. Maxine Mesinger wrote in the Houston Chronicle that the event “caused the biggest excitement and crowds I’ve seen around here in ages.” For celebrity hounds, though, the pickings at the $200-a-plate affair were slim. Morton himself was there, and Kenny Loggins, but that was about it unless you were the sort to be thrilled by a peek at MTV veejay Mark Goodman.

A Houston publicist had bet me a Classic Coke that the Dallas Hard Rock crowd would be “snottier.” I guess I owe her one. Despite six nights of previews for cab and bus drivers, police officers, neighbors, and investors and despite Tigrett’s basic peace-and-love persona, the event was a snobfest. Here, the guests seemed genuinely dazzled by the surroundings. Two MTV veejays were in attendance. But that’s Dallas for you. Whenever Dallasites see a velvet rope, they go insane.

Tigrett’s attempt to inject soul into the Dallas opening didn’t quite work out. Jammed well beyond its 450-seat capacity, the joint should have been jumping by the time Chuck Berry hit the stage after midnight, following sets by Dan Aykroyd and the resurrected Blues Brothers Band, Albert King, Bo Diddley, Carl Perkins, and Sam (of Sam and Dave) Moore. But Berry lived up to his reputation of being difficult, getting crossways with the rhythm section of his pickup band, even with a pro like Paul Shaffer helping out. His hits sounded lifeless, and his twelve-bar blues doodles did not charm. Most of the audience cheered, nonetheless, which is why rock is a food supplement rather than a passion these days. The evening was capped instead by a star-shaped centerpiece in the rotunda’s dome, lighting up, twirling, and descending to the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love.” No one seemed to mind that neither David Lee Roth nor Eddie Van Halen showed up as rumored, nor did any celebrity investors, save for Aykroyd.

Now that the last bits of confetti have been swept away and business hums along at a typically frenetic pace at Texas’ Hard Rock Cafes, it’s time to ask which establishment is better. Morton’s Houston location is, somewhat ironically, the more congenial place. There is a hint of populism to the cafe that one might not have expected from the no-nonsense businessman who created it. Its decor is funkier and includes Akeem Olajuwon’s sneakers and the golf club that Alan Shepard swung on the moon. Outside is a sculpture—assembled by the nucleus of the old Ant Farm Collective, which created the Cadillac Ranch—that consists of twelve shelves of oil-based products like STP, Janitor in a Drum, and Tide, outlined in fluorescent lights at the base. Its creators describe the piece as a “petroleum-culture diorama.” In contrast, the brass working oil-pump jack in front of the Dallas location is not art so much as show.

On the whole, though, I give a qualified nod to the Dallas restaurant. It has to be said that Tigrett’s harmonic vibes are out of sync with the elitist nature of his restaurant. There’s a private room upstairs called the Cheese Club that features dark wood paneling to give it a gentlemen’s club ambience. And the plaque bearing a Beatles quote—“The Love You Take Is Equal to the Love You Make”—rings especially hollow, given its location in the valet parking lot. But you have the sense that Tigrett is trying harder to do something special, that his true-believer relationship to rock and roll may overcome the pretensions of his restaurant. While the music at the Houston Hard Rock seems like little more than a gimmick, at the Dallas restaurant it’s the raison d’etre.

For anyone curious about what rock meant to three generations of young Americans, Hard Rocks provide archeological insights and a cult of personality along with a meal. But if someone’s looking for the heart and soul of rock and roll, he should steer to Prince’s, Kim’s, Dirty’s, Joe’s, or some other nonthematic burger joint, drop a few quarters in the jukebox and a few more on pool or pinball, and start flirting with a carhop. That’s what rock and roll’s all about.

- More About:

- Music

- Business

- TM Classics

- Dallas