In late 1835 the Mexican Army sent a hundred cavalrymen to the town of Gonzales to retrieve a cannon it had lent to the settlers a few years before. Revolutionary sentiment was mounting, and the colonists were not jazzed about the prospect of losing a valuable weapon. Aimless shots were exchanged for a few hours, with a few casualties.

As in so many episodes of the Texas Revolution, there’s a conspicuous mismatch between the heroism ascribed to the day’s events after the fact and what actually happened. The Battle of Gonzales was, to be sure, the first battle of what would become the revolution—the Lexington of the Lone Star State. But in military terms it was a skirmish of little importance, and the six-pounder cannon itself was, truthfully, a pretty dinky weapon. It was slow-firing and inaccurate, useful mainly for making a lot of noise. Eventually, the Mexicans withdrew.

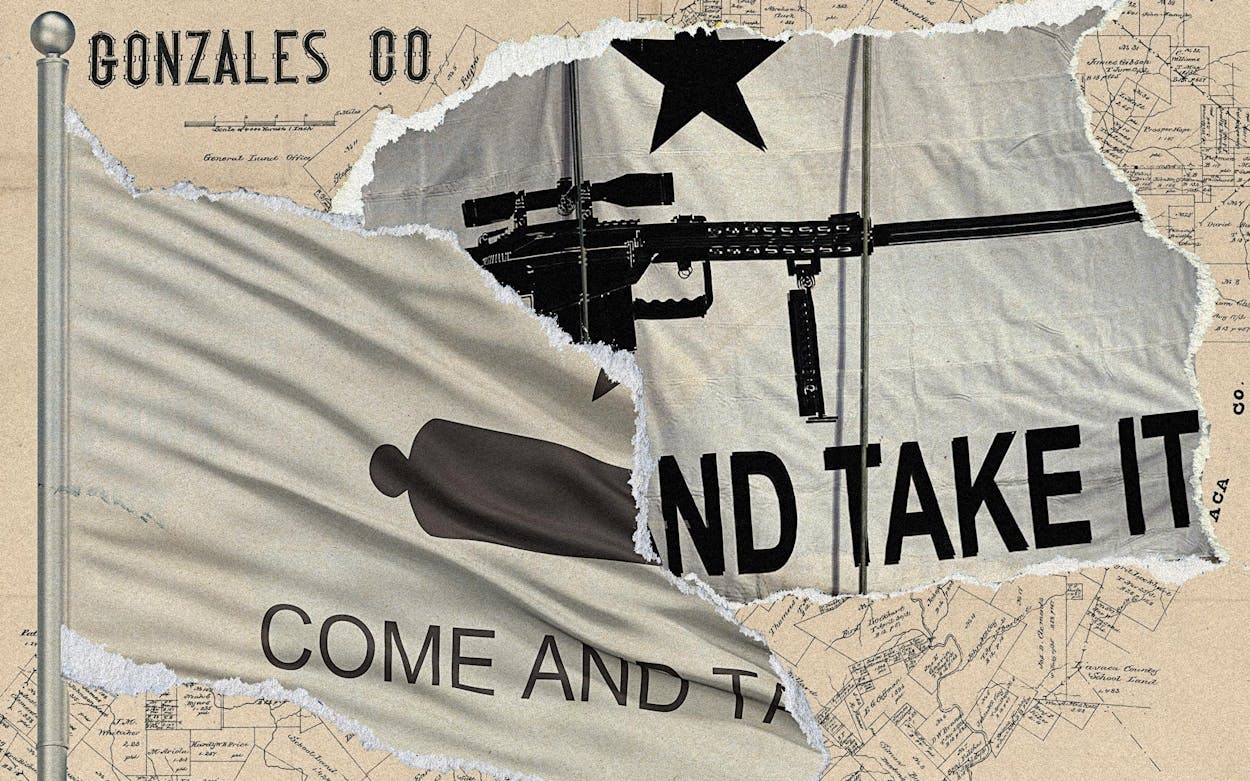

The greater irony: Gonzales’s immortal legacy was secured not by the desultory fighting near the town but by the graphic design skills of women from Gonzales. According to one account, mother and daughter Sarah and Naomi DeWitt made the flag for the militiamen out of Naomi’s wedding dress. “Come and Take It,” the flag says—an old wartime taunt, in a smart-looking sans serif font. Above it is a silhouette of the cannon’s barrel, and above that is a star, all black on a white background. It’s spare, modern, and memorable. Nationhood may be secured in war, but it is often forged through aesthetics.

The Gonzales flag has become much more common in the past few decades, in a different form: with an AR-15 or other modern assault rifle in place of the cannon. This version seems to have originated in the nineties, but it has proliferated. It appears on bumper stickers and at pro-gun rallies across the nation. Rock star and right-wing provocateur Ted Nugent sells a version of it in his online store. In 2021 I saw a teenager driving a motorized rickshaw in Cairo with the AR-15 version decaled on the back, a sight the colonists of Gonzales probably would have had difficulty interpreting. The new Gonzales flag is effective iconography in part because it looks cool and in part because it ties today’s efforts to maintain and expand gun rights to one of the oldest and proudest moments in Texas history, an act of defiance against oppression.

But Texas’s history with firearms is weirder and more varied than that. In the days of the Old West, the state tried desperately to rein in gun violence. Texas banned the carrying of handguns, and cattlemen associations begged cowboys to stop packing six-shooters, which, when brought into bars, frequently led to violence and death. Terrible bloodshed in Texas and elsewhere brought about by new weapons, such as the tommy gun in the twenties and thirties, helped inspire the first federal firearms law, and some of the worst pre-Columbine mass shootings happened here. It wasn’t until 1995 that gun regulations started to be relaxed in the state.

Texas Monthly’s archives reflect that change. In stories from the seventies and eighties, guns are everywhere, but they’re mere tools, mostly passionless and apolitical ones made sometimes terrible and sometimes noble by their owners. Folks fetched hunting rifles to shoot back at Charles Whitman, the UT Tower sniper, and that was to be expected. Over time, and especially after the mid-nineties, it became common to talk of a “gun culture” that was more fetishistic, where firearms became deeply ideological symbols of self-determination for a relatively small group. The percentage of Texans who own guns has been dropping continuously since 1980, while a small number of people own more and more guns. In polls, support for additional gun regulations remains consistently high. But the fervor of those who have built their identities around gun ownership has only grown. The new Gonzales flag is the icon of that fervor, which pretends to be timeless but is weirdly new.

It’s a mirror in one other way. Texans have always liked to imagine themselves as plucky underdogs succeeding against the odds, frontiersmen awaiting the clip-clop of Mexican dragoons. It’s less true than ever: We’re the overdog now. We make our own choices, and decisions made here in boardrooms and in the Legislature affect countless folks who have no say, both inside and outside the state.

If the Gonzales cannon looks today like a toy, the AR-15 is pure power, an overdog’s gun. A few in the hands of a well-trained team would have devastated both sides in Gonzales that day and an elementary school classroom besides. No outside force is coming to reimpose “tyranny” in Texas anymore. We have only ourselves to credit for the future we’re giving to our kids. If that future is one of school-shooting drills and periodic grocery-store bloodlettings, well, the Mexican Army isn’t to blame.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Revisiting the Cannon.” Subscribe today.

Image credits: Gonzales Map: Texas General Land Office/Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Gonzales